Hello everyone:

First, a housekeeping note: It’s come to my attention that readers have tried to respond to my posts by replying to my emailed essays. Until now, that hasn’t worked. Those emails disappeared into the aether, never to be seen again. I have patched that hole, and so it is possible to respond directly to me. That said, I’d like folks to consider putting their responses to the substance of the writing in the Comments. If you want to say Hi, or pass on a less public note, please do so. I’m always happy to hear from you.

This week in curated Anthropocene news, I have four recommendations on whales, sugar, peat, and the ethics of wooly mammoths:

1) Something wise and lovely by another Substack writer, Nicie Panetta, from her newsletter Frugal Chariot. This post is called Close Encounters and ties together her personal experience with a sperm whale with a fine review of a fascinating new book called Fathoms: The World in the Whale, by Rebecca Giggs. Here’s a sample from Fathoms, drawn by Nicie from a passage describing all that can be found of us inside the whale:

“We struggle to understand the sprawl of our impact, but there it is, within one cavernous stomach: pollution, climate, animal welfare, wildness, commerce, the future, the past. Inside the whale, the world.”

2) Want some really, really good reasons not to buy cheap commercial sugar (like Domino) or the products that use it (like Hershey)? How about Haitian and Dominican workers slaving away for a few dollars a day in a lifetime of debt, disease, chemical exposure, and an absence of real human rights or healthcare or education? How about a monocultural landscape of sugar cane plantations soaked in pesticides and herbicides? How about sugar companies owned by billionaires donating some of the many millions of dollars they earn in product price support from the U.S. government back to U.S. politicians (of both parties) who protect their interests? Here’s an excellent investigative piece in Mother Jones.

3) Why we need to love peat: Peatlands store five times as much carbon per square meter as the Amazon forest, and they exist all over the world, harboring rich, diverse habitats found nowhere else. They continue to be drained for agriculture and cut as a traditional source of fuel, but protecting them instead will store huge amounts of carbon. But we have to do it quickly, before a warming climate dries them out and turns them into massive carbon emitters, as has been happening in the Russian Arctic. Good restoration work is being done around the world. Check it out here at YaleE360.

4) A now well-funded plan to create “mammophants,” an elephant-embryo proxy for wooly mammoths, via CRISPR technology, in order to build a population of mammoths to turn Siberian tundra into grasslands. Why? Aside from the revolutionary “gee-whiz” factor of de-extincting mammoths, it’s hoped that recreating grasslands will slow climate change in the Arctic.

Enjoy. Now on to this week’s writing:

This week I’ve finally decided to dig into something I’ve mentioned many times in passing: the unsustainable growth of human population. It’s not a topic that wins friends or votes, but I think it’s the core feature of the Anthropocene. I’ll spend some time here this week looking at the numbers and justifying my conclusion, as best I can.

In weeks to come, though separated by other topics and not on any particular schedule, I’ll follow up with other essays on population. There are many good questions to sort through, particularly this one: Would population matter if we eliminated fossil fuel use, farmed responsibly, ate mostly plants, reduced consumption, restored and regenerated landscapes and at-risk species, and created an equitable global society which did not reward wealth and punish poverty? In other words, would population matter if humans treated both the Earth and each other with a full measure of respect? I would argue that it does. There are simply far too many of us, with at least another billion or two on the way.

I’m sure many of you will have your own good questions. For one thing, talking about population has a long, ugly racist history linked to eugenics and other violations of basic human dignity. For another, many people falsely assume that proposals for slowing population growth or reducing population pit human rights against state control. And then there is the obvious hypocrisy of affluent consumer nations worrying about birth rates in developing nations. We’ll work through those in further essays, and in your Comments, if you’re inclined to share them.

For now, I’m focusing on the raw numbers. And to help me do that, I’d like each of you to open the Worldometer population clock in another tab. I’ve tried very hard to figure out a way to embed a pop clock widget into this email, but without any luck. To my mind, there is nothing like watching the clock spin like a gas pump dial while reading or going about the various mundane tasks of my day. (Don’t worry too much about me; I don’t do this often.)

Once you have that set up, you should know a little bit about it. The Worldometer clock is an algorithmic estimate of human population, based on demographic science done by the U.N. Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs and the U.S. Census Bureau Population Division. As Worldometer notes, the “current world population figure is necessarily a projection of past data based on assumed trends,” all of which is regularly updated. In other words, there’s no army of volunteers with clickers marking each birth and death in every home and hospital on the planet. The main thing to note is that this is a carefully estimated measure of net growth – births minus deaths.

If you scroll down the population clock page, there’s plenty of demographic info to keep you busy. But for now, just watch the clock for a while. It has an odd little stutter, like a salsa rhythm, with one step back for deaths and two steps forward for births. The births are relentless: an average 2.4 additional souls per second.

With about 144 additional people arriving per minute, if this essay is a fifteen-minute read for you it would also be a 2160-person read.

At a rate of 220,000 new arrivals per day, that’s the equivalent of a city of a million people – Austin, for example, or two Atlantas – appearing every five days, the population of Los Angeles every twenty days, and another Beijing every 101 days. Each year, another 10 New Yorks.

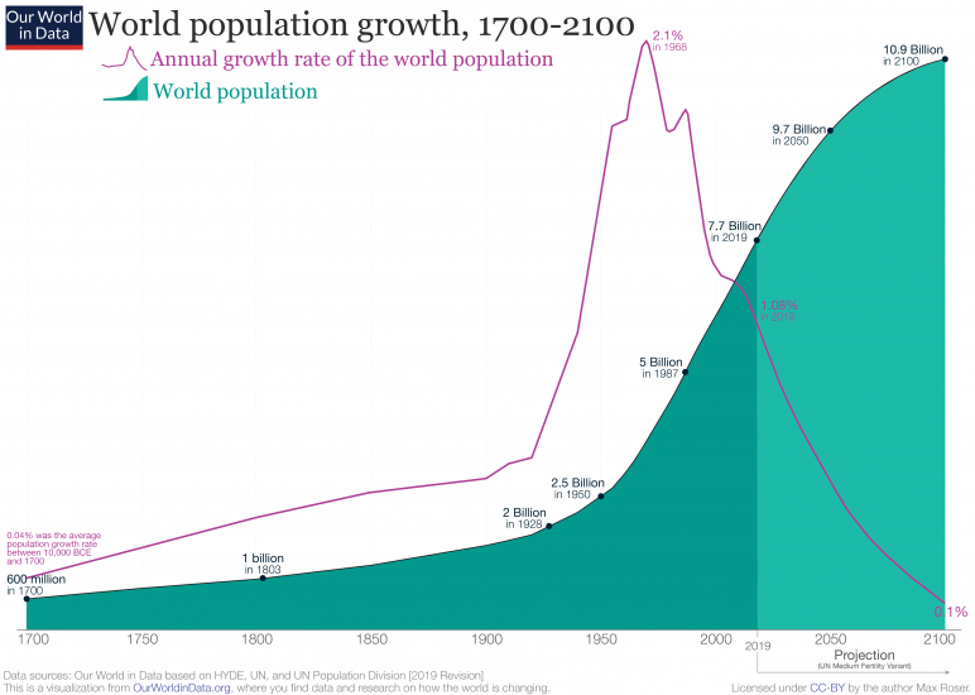

One of the finest and most influential scientists of the last few generations, E. O. Wilson, wrote in a 2002 article for Scientific American, “The Bottleneck,” that “The pattern of human population growth in the 20th century was more bacterial than primate.” That is, we’ve looked a lot more like microbes in a well-fed Petri dish, doubling our numbers in a flash, than the stable offshoot of apes that we were for millions of years. Modern humans appeared 200,000 years ago, and the shift from hunt-and-gather to settlement began about 12,000 years ago. However you define human history, it took us all of human history, until 1804, to reach one billion, but just 220 years later we’re poised to reach 8 billion. The other analogy for our recent growth that comes to mind is a wildly successful invasive species – zebra mussels, kudzu, earthworms, cane toads – all of which, not coincidentally, were spread by our wildly successful selves as we’ve shuffled species across continents like cards before a poker game.

Wilson continued: “When Homo sapiens passed the six-billion mark [in October of 1999] we had already exceeded by perhaps as much as 100 times the biomass of any large animal species that ever existed on the land. We and the rest of life cannot afford another 100 years like that.” As I’ve noted here a few times, and no doubt will again, it’s been calculated that 96% of all mammal biomass on Earth today are humans and our livestock. Every photograph, video, documentary, or book you’ve ever seen that includes a wild mammal – whether elephants, ungulates, cats, dogs, rodents, or bears – now represents only 4% of the total. Likewise, poultry biomass is three times greater than that of wild birds. We and our livestock outweigh all of the planet’s vertebrates, other than fish.

Which gets to one of my essential points. The question of overpopulation isn’t merely a societal quandary about how many humans the planet can support. Any debate about human population that obscures or ignores the cost to the balance of life on Earth isn’t worth having, in part because all life deserves to live in some version of a rich, global, diverse fecundity, and in part because for our sakes it must exist. We’re crazy to think we can live without it.

We think we live in a house, car, and office, but those are just our clever snail shells within a global living, breathing, interdependent biosphere. We’re still creatures of forest and field. The problem is that we’re erasing the forests and fields.

This isn’t a radical environmental hypothesis or desire. The science of our reliance on biodiversity for our species’ survival, from pandemics to pollination to public mental health, is clear. E. O. Wilson writes in his book, The Future of Life, that “Perhaps the time has come to cease calling it the ‘environmentalist’ view, as though it were a lobbying effort outside the mainstream of human activity, and to start calling it the real-world view.”

Which means that the real-world view of population growth numbers matters too, unless there’s some way to magically reduce the impact of today’s nearly 8 billion people to the impact of a population level that predates the large-scale erasure of plants and animals. (As noted, I’ll explore that desire to reduce impact rather than reduce population in another essay.)

The numbers matter because what we think of as the daily needs of nearly 8 billion people (defined and expressed very differently in poor and rich nations, of course) are unraveling the planet. A 2020 analysis published in Nature found that, astonishingly, man-made stuff now outweighs all of life on Earth. The authors measured our output of several substances – concrete, asphalt, brick, glass, metal, plastics, and wood/paper products – over the past century and found that by 2020 our stuff had drawn even with the weight of all life. Plastics alone outweighed all land and sea animals. And the study’s accounting didn’t add in all the waste from producing these daily materials, nor did they add in the weight of humans, our livestock, our crops, our earthworks and mining waste, or the fossil-fuel production of our atmospheric CO2. The mass of CO2 alone, if added, would mean we began to outpace the production of nature back in 1996. It’s hard to imagine a gas having so much mass, but not if you remember it’s being produced by billions of people burning tens of millions of years of stored fossil fuels in just a few decades.

The numbers matter because even though the global population growth rate has slowed considerably, any growth upward from 8 billion happens incredibly fast. The current global growth rate is 1.05% per year, down from the all-time high of 2.09% just after I was born in the late 1960s. But that seemingly minuscule

1.05% growth rate adds up now to about 81 million additional humans every year – that’s nearly the population of Germany – whereas in 1970 with fewer than half the people but at double the rate it meant another 72 million.

The numbers matter because as individuals, cultures, nations, and civilization generally turn slowly to face and respond at least halfheartedly to the climate and biodiversity crises that our growing population has created, we have to do so in the context of another Germany of babies arriving every year. Look again at the Worldometer pop clock for a moment and think about a particular environmental issue that matters to you. How much harder is it to restrain CO2 production in the context of that spinning wheel? To provide food and clean water and housing and cooling to everyone in a warming climate? To protect migratory birds and pollinators in rapidly developing nations? To reduce rapidly accelerating extinction rates, or protect coral reefs? To protect whole ecosystems from human use? Here’s E.O. Wilson one more time, from the “Bottleneck” article:

“The constraints of the biosphere are fixed. The bottleneck through which we are passing is real. It should be obvious to anyone not in a euphoric delirium that whatever humanity does or does not do, Earth's capacity to support our species is approaching the limit.”

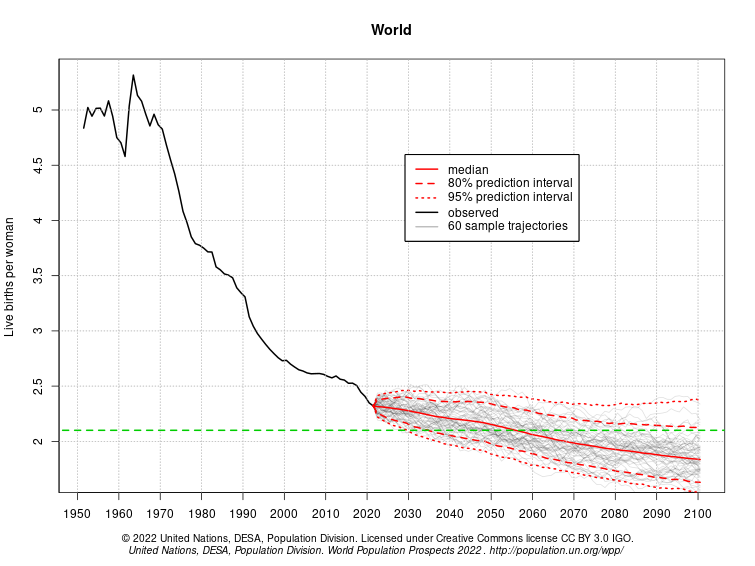

The numbers matter because even a tiny tick upward in global fertility rate explodes the prospects for dealing with these crises. The current global fertility rate is 2.4 births per woman, down from 5.0 births per woman at the 1965-1970 peak. The U.N.’s median projection for human population by the year 2100 is about 10.9 billion. Should fertility rates jump up by half a child per woman, the prediction jumps to 16 billion just eighty years from now. I don’t think anyone expects this, but like a runaway train it gets your attention. Alternatively, if the fertility rate dropped by half a child to 2.0, population in 2100 would be expected, after larger generations pushed through, to drop below 7.5 billion, slightly less than today. (A 2.1 fertility rate is considered zero-growth or “replacement rate,” i.e. two children replacing their parents, with the 0.1 added on to account for infant and child mortality.)

A quick note about projecting population in 2100, or even 2050: No one knows how it will play out. Human demographics are complicated, particularly in the Anthropocene. Factors include whether people continue to live longer lives, changes in child mortality, and particularly the age that women begin having children and the size of the family they desire. We especially don’t know what kind of turbulence at a global scale will impact the capacity, or desire, of humans to produce and care for children over the next several decades. Successive waves of climate refugees, for example, or a drop in global crop yields, or political upheaval in the face of such challenges, could have a major impact. As would a pandemic more prolonged or mortal than the current one.

Alternatively, if major advances in reducing CO2 appeared, that might reduce would-be parents’ concerns about having children. (A new survey out this week found 40% of young adults around the world are hesitant about having kids in the midst of the climate crisis.) If there were significant success in today’s global campaigns to provide education to girls and women and to fund comprehensive family-planning services (more on these vital efforts in another essay), fertility rates could drop and bend the 2100 trend lines in the right direction.

That said, it’s safe to assume that current trends are a reasonable guide. Earlier U.N. demographic projections for 2050 and 2100 were different than the new ones, and there are other predictions out there which are different even now. The Wittgenstein Center World Population Program projected that global population will peak in 2070 at 9.4 billion and then drop to 9.0 billion in 2100. A 2020 study in the Lancet predicted that fertility rates will drop to 1.7 by 2100, with a peak population in 2064 of 9.7 billion declining to 8.8 billion in 2100. (Their optimism is rooted in assumed progress in the empowerment of women globally.) These three predictions range from 10.9 to 8.8 billion by century’s end, a gap wide enough to contain present-day India and China but otherwise statistically similar. It’s unlikely that any of them will be wildly inaccurate, unless new strong, long-term, persistent forces are revealed or some vast unprecedented upheaval occurs.

It’s tempting to look at today’s news, particularly the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, for hints about how the numbers might change. But population and population growth are both extraordinarily massive ships - weighing as much as all life on Earth – to try to turn. Global deaths from the pandemic are officially counted at 4.7 million, as of late September 2021, while the Economist estimates the true number is more than 15 million. Setting aside the reasons for such disparate estimates, for our purposes here the difference is 5 days or 15 days. That’s how long it would take to replace the pandemic dead, statistically speaking, at 2.4 babies per second.

The current virus has had an estimated mortality rate of roughly 3%. If it were to mutate into a variant as deadly as two related coronavirus outbreaks, SARS in 2003 (14% mortality) or MERS in 2012 (33% mortality), neither of which was particularly infectious, all hell would break loose in human society. But with effective vaccines and social hygiene already established, it’s likely that losses would be largely contained (with the worst effects being felt, of course, in those nations still deprived of vaccines). Again, for our purposes here, even if a billion people perished, an unthinkable scenario, recent population growth suggests that they would be “replaced” in about twelve or thirteen years. This is a grotesque bit of data with too many variables to make sense of, so I’ll move on. I note it only to reinforce my point about current growth rates.

And anyway the path forward is through a reduction in birth rates rather than increased mortality. The good news is that, as of 2021, 91 nations have fertility rates at or below replacement levels. If the world had a fertility rate like those in Italy (1.1) or Japan (1.4), population would halve by the end of the century. In that time, Japan is expected to decline from 128 million a few years ago to 53 million; Italy, likewise, is predicted to drop from 61 million to 28 million.

I should note that there is a lot of fear about population decline. Economists, reared on the insane fiction of constant growth, are generally bewildered by it. Governments have few ideas for how to cope with it. Nationalists and racial purists see it as a direct threat. Societies will have to restructure and reimagine and innovate. All this deserves more writing another day, but for now just note that as the 21st century winds along there will be a very strange tension between the need for population decline and a clamor for more babies to feed the economy.

Finally, let’s take one more look back at the Worldometer clock, and remember that there is extraordinary meaning in each tick and each tock, each life gained and each life lost, in a great embracing tangle of love and grief. And that’s another of my essential points, that these lives that turn the dial are as vital as our own and as beautiful as those of cedar trees and migrant hawks and spores and anemones, and perhaps the best way to honor the production of vital, beautiful life is to give it space on Earth to thrive. How we do that is a question for another day, but perhaps I’ve made the start of a decent case for why we should do it.

One more note: If you’re looking for a way to help nudge the numbers lower, you can fund efforts for family planning and the empowerment of girls and women everywhere. Good places to start are here, here, and here.

Another great essay. To me, this might be the most important component to the climate crisis. We need to reduce population and reduce emissions. But we must do more than just reduce our billions of footprints.