A Beef Between Human Beings and Physics

5/5/22 – A review of the recent IPCC report on climate mitigation

Hello everyone:

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the post to read this week’s curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing.

This week’s title is borrowed from the ever-brilliant Bill McKibben, who wrote in a recent post called “Who Gets to Define Reality? A Search for the Climate High Ground” about whether climate realism is better expressed by pessimists or activists. A dour realist who knows how unlikely it is that we’ll cut global emissions in half by 2030 may be right, but if they insist on only that reality then they’re forgetting the larger truth: Failure to do more than what seems possible is more than failure. It’s a radical, brutal, and perhaps apocalyptic disruption of human society and life on Earth. Here’s McKibben:

Realism is often defined as some middle ground between opposing sides. And in controversies between humans, that’s at least a reasonable idea… But the climate crisis is not a beef between two camps of people, ultimately. It’s a beef between human beings and physics. And since physics is implacable, we would be well-advised to do everything we possibly can to meet its dictates.

If we mustered all available political will, we could make change very fast, just as we made tanks very fast at the start of World War II. Climate activists, it seems to me, are more realistic than naysaying academics, if only because they know we have very little choice.

The Working Group III report on Climate Change Mitigation from the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change), out a month ago, details how poorly our scuffle with climate physics is going. As a species, we’re increasingly talking about backing away from the unwinnable fight, reducing our emissions, redesigning our energy infrastructure, and obeying the laws of physics, but so far we’ve only managed to slightly reduce our aggression. We’re still pretending we can win, but with a bit less vigor. The ref is eyeing us as we wobble around the ring, and wondering how many more years of this we can take.

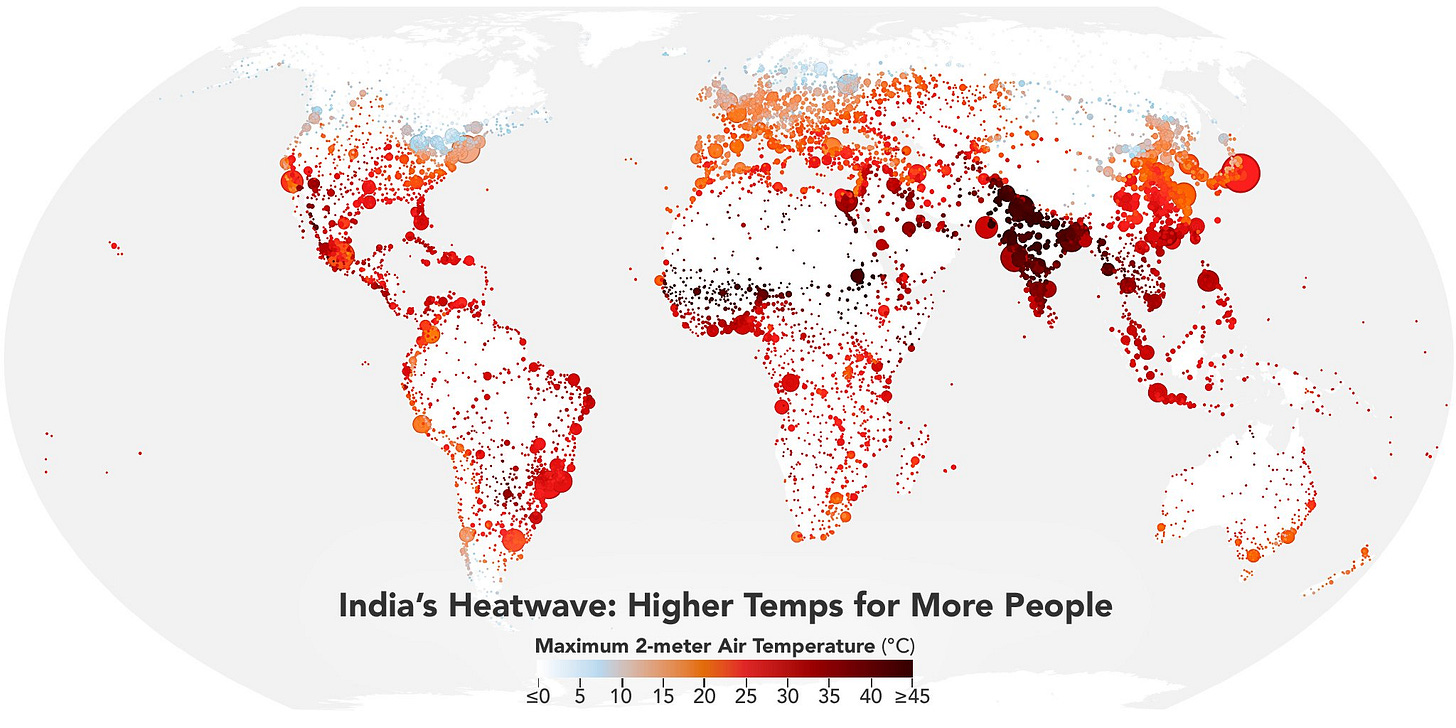

A quick glance at today’s news reveals how physics is holding its mirror up to our actions. First, the extreme heat wave in India and Pakistan impacts nearly a fifth of humanity, with northern India seeing temperatures of 45°C (113°F) or more. The map by Joshua Stevens above provides some perspective. This is merely the temperature, though, without taking into account the humidity. The Vice article I link to above explains that a “wet bulb” temperature of 35°C with high humidity will be fatal for most humans, and that at a wet bulb 32°C (90°F that feels like 130°F) even heat-adapted people cannot carry out normal outdoor activities. Parts of India and Pakistan experienced several days of wet bulb temps at or above 30°C. Earlier climate models projected that these kinds of heat waves wouldn’t hit until the mid-21st century, but here they are.

Second, closer to home here in the US, in the midst of the driest two decades in 1200 years, the mega-drought has brought Lake Powell and Lake Mead to their lowest levels ever. Federal authorities are forced to make decisions regarding how to balance distribution of what little water remains between electricity generation and water supply for millions of homes. The folks making these decisions have no protocol in place or precedent to guide them. They are in uncharted territory because these dams, like so much Anthropocene infrastructure, were built with the delusion that humans could fundamentally alter the planet without consequences.

And third, looking ahead, if we’re foolish enough to ignore the dictates of physics and to let the fossil fuel industry coach us into maintaining high emissions for decades to come, a recent study predicts that the oceans will suffer a mass extinction by the year 2300. This would rival the five other times in the planet’s history that life on Earth was largely wiped out. (Given that every prediction of climate change and its impacts has so far been too guarded or optimistic, I have to believe that our descendants should expect this kind of outcome much sooner than 2300.) Already, coral reefs are in steep decline and a variety of changes to ocean chemistry are impacting populations of marine species worldwide. Last year, scientists recorded the ocean’s highest temperature and lowest oxygen content since record-keeping began.

Believe it or not, the good news here, according to the Times, is that

reining in emissions to keep within the upper limit of the Paris climate agreement would reduce ocean extinction risks by more than 70 percent… In that scenario, climate change would claim about 4 percent of species by the end of this century, at which point warming would stop.

There are perhaps a million species in the oceans. So the optimistic reading here is a loss of 40,000 marine species if we manage to do all the climate mitigation that we don’t seem to be doing.

UN Secretary-General António Guterres, who talks very much like a climate activist, says in his video introduction to the IPCC’s WGIII report that “Climate activists are sometimes depicted as dangerous radicals. But the truly dangerous radicals are the countries that are increasing the production of fossil fuels.” He goes on to say that wealthy economies and corporations

are not just turning a blind eye; they are adding fuel to the flames. They are choking our planet, based on their vested interests and historic investments in fossil fuels, when cheaper, renewable solutions provide green jobs, energy security and greater price stability.

Here’s that speech:

The 278 scientists from 65 countries behind the WGIII report do leave room for some optimism, largely by mapping out what can be done and describing how much of that is already doable with the knowledge and technology we have on hand. Here’s the IPCC’s video overview of that optimism, complete with heart-swelling score:

I wrote last week in my introduction to the WGIII report that the Summary for Policymakers was worth reading. I guess I’ll stick by that claim, but I want to remind you again that it was watered down a bit by fossil fuel interests, and to say again how much of a pain it is, especially in its current form, to process. Thus, you might read this version instead from the International Environment Forum, because it offers a clean version of the Summary without footnotes or other parentheticals. Or you might zero in on a slimmed-down version of the Summary the IPCC calls its Headline Statements. It’s the exact same language, but a much thinner selection.

To be clear, the headline statements are a reduction of the full report’s 3000 pages to about 3 pages, but because of IPCC’s outline structure if you want more on a particular point you’ll know exactly where to find it in the Summary or the full report. For example, if you read the B.4 statement on significant decreases in costs for alternative energies, you can then refer to B.4 in either of the longer documents for a deeper dive.

To begin, though, you can read my slimmed-down rewrites of many of the report’s points right here. There are four sections, from which I’ve created about three and a half pages of bullet points. Since the full list would make this week’s post too long, and because no one can comfortably read so many bullet points (enough for the St. Valentine’s Day massacre, I think), I’ll give you just the first section now, along with some relevant IPCC explainer graphs. The other three sections will come next week. Note also that the section headings I’m using are the same as those in the report.

As you read these points on the trend of how we are and aren’t coping with the existential crisis poised by our heating of the atmosphere with greenhouse gases, remember Bill McKibben’s point that we are not engaged in some political gambit or squabble. We are instead at war with physics, i.e. with the reality of how the planet works. There is no victory other than admitting defeat.

I often think, in moments like this, of the oft-forgotten difference between logical action and rational behavior. Logic can, and often does, have a false premise. (Constant economic growth is the perfect example here.) Rationality is based in the real world, as best we understand it.

So, without further ado, let the first bullet points fly:

Recent Developments and Current Trends

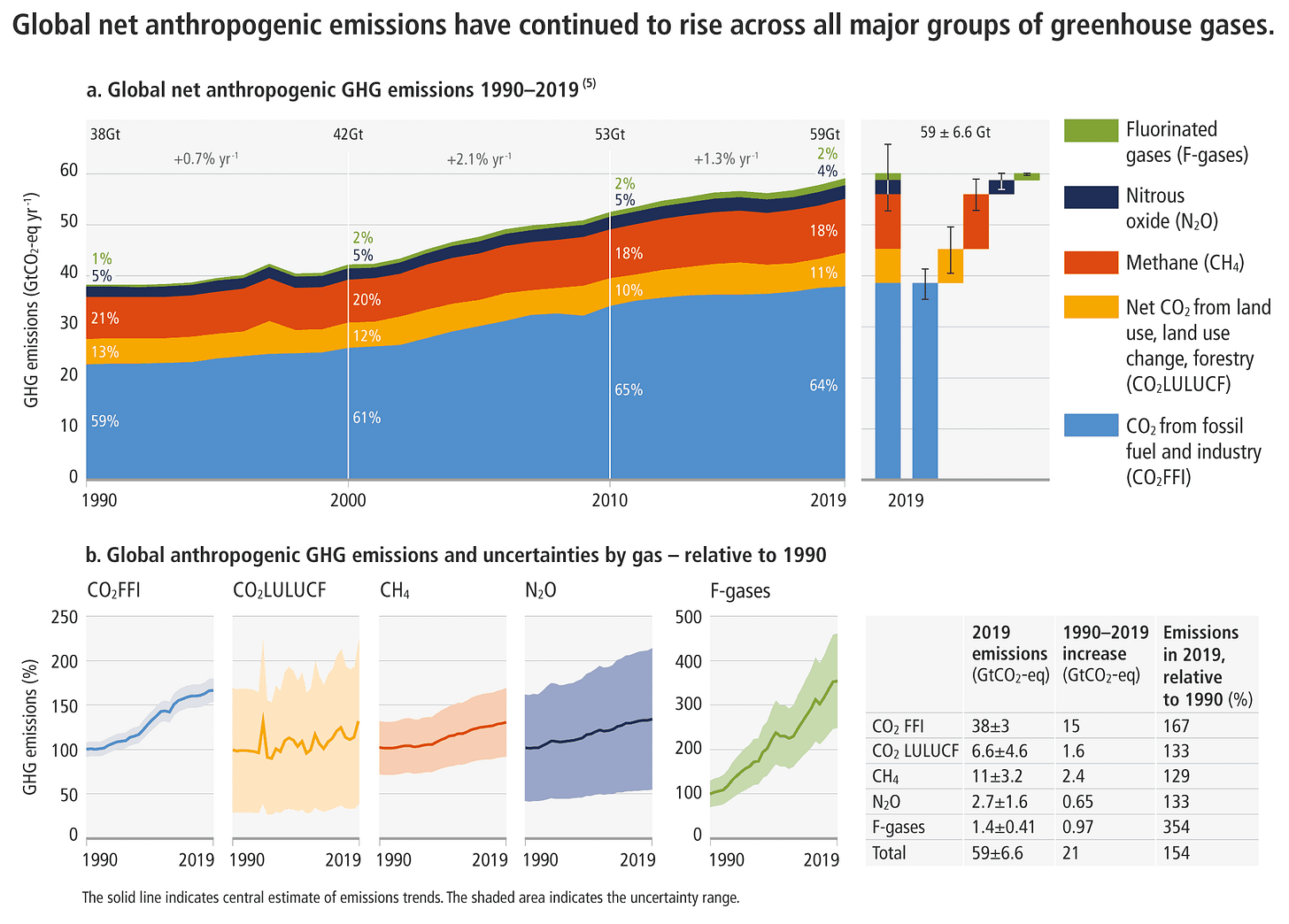

We are still increasing our emissions of greenhouse gases each year, but the growth has slowed.

Emissions increased 12% from 2010, about 1.3% per year, which is better than the annual 2.1% increase of the previous decade.

Emissions increases were across all of civilization, including energy, agriculture, and transportation.

There were significant reductions in emissions because of the rapid expansion of renewable energy and because of improvements in energy efficiency, but they were not enough to counteract increased emissions from industrial activity and global population.

It’s not hard to reduce emissions while also keeping an economy growing. 18 nations have done so, according to the report. The countries aren’t named, but data from the Global Carbon Project lists 19 nations where “the pre-pandemic annual carbon dioxide emissions were at least 10 million metric tons less in 2019 than in 2010”: the US, the UK, Germany, Japan, Italy, Ukraine, France, Spain, Greece, Netherlands, Mexico, Finland, Singapore, Denmark, the Czech Republic, Belgium, Poland, Romania, and Sweden.

Between 2010 and 2019 there were steady and dramatic decreases in the cost of solar energy (85%), wind energy (55%), and lithium-ion batteries (85%)

In the same span, there was a 10-fold increase in the deployment of solar energy and a 100-fold increase in the production of electric vehicles. It’s important to note that these improvements were due in part to good policy, which provided funding and other incentives.

Funds flowing toward climate mitigation and adaptation have increased by 60% since 2013 but have recently slowed. Overall, funding has not been nearly enough to meet previous promises (e.g. the Paris Agreement) or current goals.

If we continue using the world’s current fossil fuel infrastructure through its projected lifetime – neither adding to it nor eliminating any of it – then we’ll be on track to warm the planet by at least 2°C.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In curated Anthropocene news:

For those of you who wonder what “nature writing” means in this era of extinctions, flames, and IPCC reports, here’s an excellent short essay at LitHub by Michelle Nijhuis, author of Beloved Beasts: Fighting for Life in an Age of Extinction. Rather than nature writing, she says, let’s call it “survival writing.”

From the New Yorker, an exploration of the strange, varied, and rapidly developing technologies for solving the missing puzzle piece of the renewable energy revolution: energy storage.

How would you like to get sued by a lake? Again from the New Yorker, an attempt to give a lake in Florida legal standing in a fight to limit harmful development.

From National Geographic, an excellent article on why the protection and rehabilitation of old growth forests are necessary for both the climate and biodiversity crises.

From NPR, the U.S. Office of Management and Budget recently reported that increasing and worsening floods, drought, and wildfires could cost taxpayers $2 trillion annually by the end of this century if we don’t act now.

The icons of Antarctica, Emperor penguins, are threatened with extinction due to climate change by 2100.