A Road Slowly Taken

1/9/25 - Jimmy Carter, hitchhiking, kindness, common sense, and governance

Hello everyone:

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read this week’s curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to the writing:

Many years ago, on a hitchhiking trip during a college spring break - to New Orleans from western Massachusetts - I was lucky enough to catch a ride with a trucker who took me from a wintry truck stop outside Hartford, CT, to a warmer one outside Knoxville, TN. The driver seemed like a decent guy, but a life marked by tragedies had left him in a dark place. One of his hobbies, he said, was taking photographs of terrible highway accidents.

Among the stories he told me was this: he was ex-military, and had taken part in the Carter administration’s failed attempt to rescue the U.S. hostages held at the Iranian embassy in 1979. At the operation’s secret desert staging area, a sand-choked helicopter crashed into a plane, killing eight and injuring several others, including my driver. He woke up in a hospital in Germany.

This story came back to me when I heard the news of former President Jimmy Carter’s death. I took a little time to think back across my life and consider its few points of confluence with the generous Georgian soul now known more for his life’s good work - eradicating diseases, promoting peace, protecting free and fair elections, building homes for the homeless, and much more - than for his one term in the White House.

Another sturdy memory related to Carter was the night he lost his re-election bid to Ronald Reagan. It was the first election I paid any attention to, but my memory is not of the campaign but of my mother’s profound disappointment that a kind, ethical, and brilliant man had lost the race to a charismatic but shallow politician whose demonization of representative governance (on behalf of business interests) would make life much harder for ordinary Americans. Forty-five years later, the long cold shadow of Reagan’s perverse legacy persists, and has (again) found four more years to grow darker and longer.

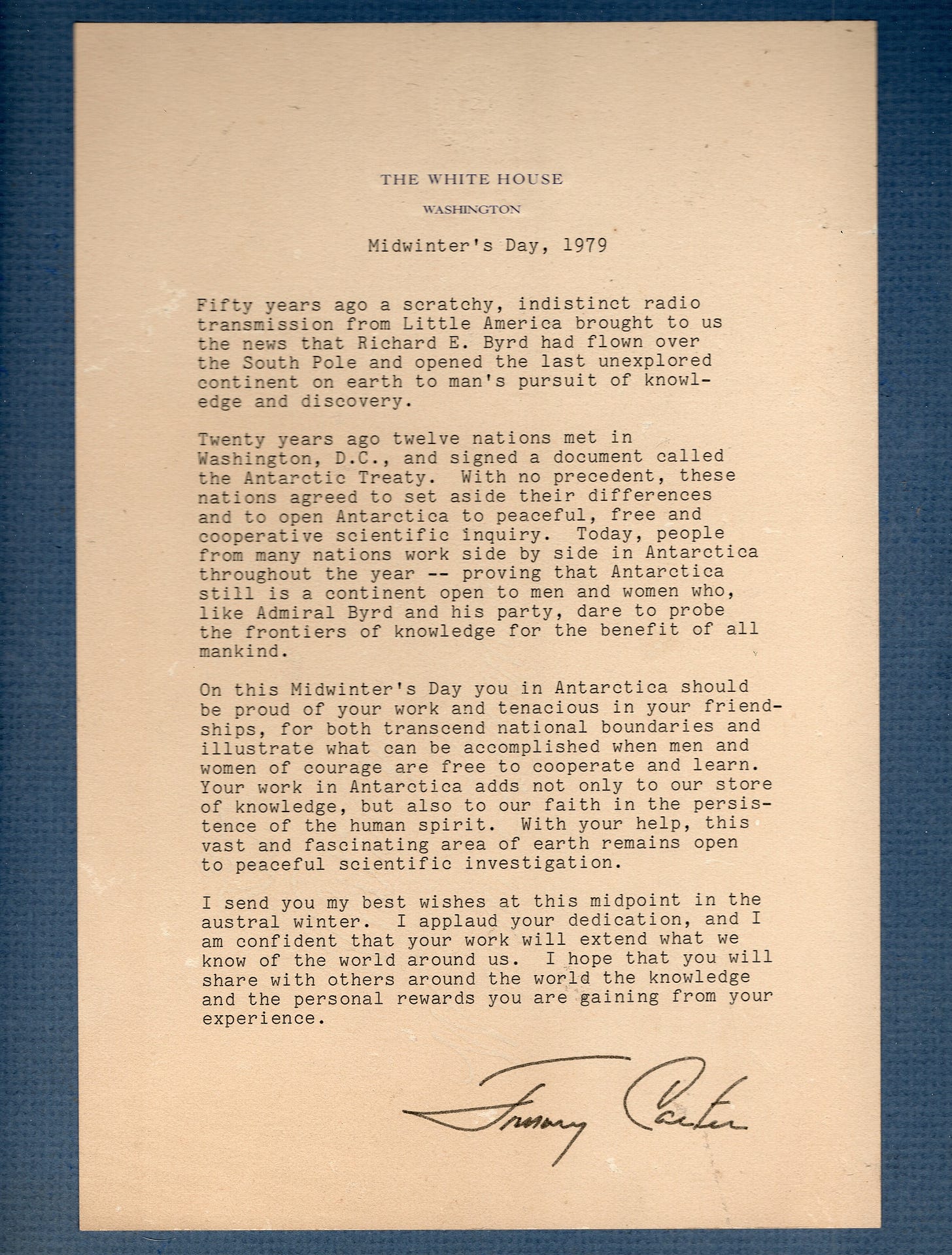

Finally, I remembered that I had in a closet somewhere a copy of the letter sent in 1979 by President Carter to U.S. staff and science personnel wintering over in Antarctica. (I found it in the late 90s, discarded, when I worked at McMurdo station.) The Midwinter Day letter from the White House, sent on the June solstice, is a tradition dating back to 1959. (Here’s President Biden’s 2024 letter.) Longer and more thoughtful than other Midwinter letters I’ve seen, Carter’s note highlights a theme that characterized his life, i.e. how dedicated personal action makes a difference:

On this Midwinter’s Day you in Antarctica should be proud of your work and tenacious in your friendships, for both transcend national boundaries and illustrate what can be accomplished when men and women of courage are free to cooperate and learn.

None of my three small memories here are particularly important as we consider Carter’s legacy, but they do help me frame my understanding of how he fits into this moment in political and environmental history.

First, there’s apparently credible evidence that Reagan’s campaign made a secret deal with the Iranian regime to delay the release of hostages until after the 1980 election. Like any politician, Carter had his weaknesses, personal and political, but may well have won that election if either the rescue attempt or his months of negotiations with the Iranian regime had paid off, keeping Reagan out of the White House and leaving a decent human being in charge of a nation in the midst of energy and geopolitical crises that had roiled much of the world.

Carter’s response to the crisis and its economic impacts included a serious effort to make the U.S. energy independent. This would lead to a vast increase in domestic coal, oil, gas, and ethanol development, but his legislation also “imposed penalties on gas-guzzling cars, required higher efficiency standards for home appliances, and provided tax incentives to develop wind and solar technologies,” as an excellent Yale e360 article on Carter’s environmental legacy explains.

That legacy is complicated, not least because the better angels of his policies - like the 32 solar panels he installed on the White House roof - were stripped away by Reagan’s administration, leaving us the wasteful, anti-environmental, fossil-fueled decade of the 1980s. As he wrote in his diary in 1978, “The influence of the oil and gas industry is unbelievable, and it’s impossible to arouse the public to protect themselves.”

When he held a press conference on the White House roof, standing in front of the newly installed solar panels, he said something to the reporters that now sounds both insightful and quaint:

A generation from now this solar heater can either be a curiosity, a museum piece, an example of a road not taken, or it can be just a small part of one of the greatest and most exciting adventures ever undertaken by the American people.

Two generations on, let’s retain some optimism and call it the road slowly taken.

A decade after their removal, half of the panels ended up in service at Unity College here in Maine, heating water for the dining hall. In 2010, a Chinese entrepreneur from Solar Valley (like our Silicon Valley) arrived at Unity to receive one of the famous panels as an exhibit for his museum. He noted that China’s dominance in the global solar energy market owed much to the fate of those panels:

“We have learned a lot from you, from your technology, your books, from your scholars," he said. "But after energy crisis, in the Reagan presidency, you throw away everything.”

President Carter had set a remarkably ambitious goal for the nation: to collect 20% of its energy from solar power by the year 2000. Only now, nearly half a century later and a quarter century after that deadline, have we managed to acquire 20% of our energy from the full mix of renewables. I’d like to think that, had he been reelected in 1980, we’d be much further down the thoughtful path Carter tried to blaze for us.

I’m not alone in this, as

in his latest Crucial Years post explains that Carter had promised enough “serious cash” for solar energy research that, had Reagan and subsequent administrations followed through on the funding, the 20%-by-2000 goal was “almost certainly achievable.” Instead, Reaganslashed federal research funding to the bone. Tens of thousands of people in the nascent solar industry lost their jobs; a generation disappeared.

The road not taken is especially poignant when we consider the larger sweep of Carter’s remarkable environmental legacy. It’s a topic worthy of a book or two, but at a glance he is known first for his visionary effort to protect vast swathes of Alaskan wilderness, in what remains the greatest single expansion of conserved lands in American history. As historian

explains in her note on Carter’s passing,Carter placed 56 million acres of land in Alaska under federal protection as a national monument, saying: “These areas contain resources of unequaled scientific, historic and cultural value, and include some of the most spectacular scenery and wildlife in the world.”… Just before he left office, Carter signed into law the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act [ANILCA], protecting more than 100 million acres in Alaska, including additional protections for the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

When my friend Bob Mrazek, a former congressman (and author, filmmaker, publisher) founded the Alaska Wilderness League in 1993, he asked Carter to serve as honorary chair. (Bob had written the law that preserved 3,000,000 acres of old-growth forest in the Tongass National Forest.) He told me recently that Carter had visited Alaska numerous times and that “his love for Alaska wildlands, and particularly the Arctic Refuge, was deep and visceral. He told me he found it a very spiritual place.”

But Carter’s environmental accomplishments extend beyond Alaskan conservation and beyond sparking the slow-burning quest for U.S. solar energy. The Climate Forward newsletter from the Times recently listed some regulatory highlights:

The Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977 sought to minimize the environmental impacts of coal mining.

The National Energy Act of 1978 included the country’s first incentives for clean energy and measures to promote energy conservation.

The Energy Security Act of 1980 went even further to promote alternative fuel sources, including solar energy and biomass.

And the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980, better known as Superfund, created a program to clean up hazardous waste sites and hold those responsible accountable for environmental damage.

The Times, however, frames these and other accomplishments - e.g. being the first president to truly empower the Environmental Protection Agency - by asking how many survived the intense efforts by Reagan’s administration to eliminate or undermine them. The EPA, for example, withered under leadership intended to sabotage the agency. That tension is a cold mirror of what to expect from a Trump administration determined to undo most of Pres. Biden’s environmental legacy and to unwind much of the regulatory state.

Even more than Biden, Carter was looking at the big picture crisis of human impacts on a small planet, and thus toward an uncertain future. In May of 1977, he directed multiple agencies “to make a one-year study of the probable changes in the world's population, natural resources, and environment through the end of the century.” This was the Global Report to the President 2000.

And, characteristically, the Baptist Carter spoke about personal responsibility and about living a moral and meaningful life in the face of that uncertain future. I am continually surprised by how much of the religiously conservative movement in this country has been co-opted by the corporate politics of consumption, waste, and ecological destruction. Carter, though, was a progressive evangelical willing to question the assumptions of Anthropocene culture. In his “Crisis of Confidence” speech to the nation, he addressed the sins of consumption:

In a nation that was proud of hard work, strong families, close-knit communities, and our faith in God, too many of us now tend to worship self-indulgence and consumption. Human identity is no longer defined by what one does, but by what one owns. But we’ve discovered that owning things and consuming things does not satisfy our longing for meaning. We’ve learned that piling up material goods cannot fill the emptiness of lives which have no confidence or purpose.

When Carter was asked by PBS a few years ago to say what he was most proud of regarding his presidency, he said

“I would say that we did what we pledged to do in the campaign,” Carter said. “We kept the peace and we obeyed the law and we told the truth and we honored human rights. Those were the things that were important to me.”

I am not a religious soul, and I find ethical guidelines much more palatable than moral strictures. Still, every time I read one of Carter’s speeches, or think about his life’s work converting moral teachings into ethical behavior, my admiration grows and I ask myself some rhetorical questions:

Why don’t we hire people for the job of President whose résumés are built on deeply ethical and humane lives?

Why don’t we hire the kind of person my mother - now in her 80s and even more disappointed with the nation’s inability to be roused to protect itself - had hoped to elect in 1980?

Why aren’t the national political campaigns as enlightened as the Antarcticans Carter praised as “men and women of courage [who] are free to cooperate and learn?”

These are rhetorical questions because the Venn diagram of profoundly ethical behavior and political candidacy is quite thin. The path to higher office runs through many lower offices. This is the kind of common knowledge which breaks our hearts.

And that, finally, brings me back to hitchhiking. I did a lot of it, and usually enjoyed it. I have some stories. Though hardly anyone talks about hitchhiking anymore (except to conjure images of danger), much less steps out onto the road to do it, it’s an ideal form of travel in an ideal world: simple, social, energy-efficient, affordable, and based on empathy and trust. Which of course means that it’s an ideal that easily falls apart, like democracy.

A system based on empathy and trust cannot work when each side is afraid of the other. Like good humane policy from the White House, hitchhiking was more common in the 70s than in the 80s. Hitchers grew afraid of drivers and drivers became leery of hitchers. Our culture told horror stories instead of travelers’ tales, despite the fact that nearly every journey was a positive one.

I will admit, though, that like democracy hitchhiking requires diplomacy, some caution, and a sense of self-preservation. My lonely Hartford-to-Knoxville trucker, for example, asked me to come to his home in Knoxville to see his album of photos of terrible accidents, but neither my interest nor my trust extended that far.

Several years ago, the New York Times Magazine ran an intriguing article on one of the world’s most accomplished hitchhikers, a smiling Argentinian who spent years traveling with his thumb and wits (and a few dollars per day) across 90 countries. The author of the article traveled through Namibia and South Africa with the professional hitcher, and had the requisite mix of wonderful experiences and dark moments that come with traveling on trust. In doing so, he had a revelation. It’s an awareness that I think speaks to Carter’s legacy in Reagan’s shadow, to the next four years of a Trump administration determined to unravel the U.S. democratic experiment, and to this long Anthropocene transition that has eclipsed all of our lives:

This, I realized, was the real magic of hitchhiking: not how it supposedly affirmed your faith in the goodness of humanity, but how it could make and break that faith, over and over again, often multiple times in a single day.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

As President Biden prepares to exit the stage, I want to start here by highlighting some of his accomplishments that are in the news. His administration has been on a high-rolling environmental protection spree lately, designating vast swathes of American coastline and interior lands as vital to the national interest in their natural state:

From NPR, Biden has banned new offshore oil and gas drilling in nearly all U.S. waters: the entire East coast, the West coast from California to Washington, the eastern Gulf of Mexico, and parts of Alaska’s northern Bering Sea. This adds up to about 625 million acres of protected continental waters. While ecologically important and politically durable, the action might be seen as somewhat symbolic, since there is no drilling happening in any of these waters.

From the Times, Biden has just named two new national monuments in California, the Chuckwalla National Monument near Joshua Tree National Park in the southern part of the state, and the Sáttítla National Monument near the Oregon border up north. Many of the areas protected by this administration have been at the request of Native American tribes; the Sáttítla site, for example, is sacred to eleven bands of the Pit River Tribe. Both of the new monuments also represent Biden’s major effort to protect sites of high biodiversity as part of his work to protect 30% of U.S. lands and waters by 2030. As the Times notes,

in creating the Chuckwalla monument, the administration has effectively carved out a 600-mile wildlife corridor of protected lands along the Colorado River and into the deserts of California.

From

and her excellent Owl in America daily environmental reporting in , a personal framing of the importance of Biden’s two new national monuments in California.From

, Heather Cox Richardson considers the sweep of Biden’s latest environmental initiatives and writes that he has conserved more U.S. lands and waters - over 670 million acres - than any previous administration (surpassing Jimmy Carter). And the White House notes that this achievement comes on top of having “deployed more clean energy, and made more progress in cutting climate pollution and advancing environmental justice than any previous administration.”Richardson also cites

in a disturbing observation of how the new Republican-controlled Congress has rewritten its rules to make the selling-off of federal public lands to the states much easier. Siler does an excellent job laying out the problem and, better yet, links to an older piece he wrote for Outside that explains why we don’t want states managing public land:States should manage the public lands within their own borders, right? It sounds like one of those common sense, local management, small government things that will be in the citizens’ best interests.

It’s actually exactly the opposite.

That's because the federal government is mandated to manage public lands for multiple uses. So for-profit enterprises, like logging and drilling, need to co-exist with folks who want to hike, bike, and play on those lands, as well as the wildlife that already lives there. In contrast, states are mandated to manage their lands for profit, which means logging and drilling take precedent over public access and environmental concerns.

And a few lovely stories for you:

From Reasons to be Cheerful, an inspiring and bittersweet story of a woman in L.A. who has spent the last few decades working tirelessly to revitalize the concrete wasteland that has swallowed up the Los Angeles River.

From the always-amazing Chloe Hope and

, “Enchanted,” another gorgeous short essay wrestling with the gap between life and the world, and between darkness and light. A three-day power outage made life difficult, butwhen night rolled in, I softened. Instead of refusing the night with artificial lights and screens, we welcomed it in with fires and candles, and in return the night saw to it that we surrendered the activities of the day. This enforced stilling felt distinctly like being parented, as though something far larger and far wiser than I was gently peeling the toys from my hands and lifting me into bed.

From

and Chasing Nature, a fun and thoughtful short essay on a tiny jumping spider - named Charles Darwin - living amidst Bryan’s collection of carnivorous plants.From

and , “the land is a being who remembers everything,” a beautiful, searching essay on her post-Helene realities in the mountains of North Carolina.From

and , an excellent and hopeful review of the progress being made to understand the rapidly warming world through our erasure of the forests that once sustained and cooled the planet, rather than merely through anthropogenic carbon emissions.

At Jimmy Carter’s funeral, his grandson spoke beautifully about Jimmy’s many deep and good qualities. I had to chuckle at one example. He shared that his grandmother and grandfather, as children of the Great Depression, had a special place on their kitchen counter where they hung their used ‘zip-lock’ bags to dry after cleaning them and in order to reuse them. The crowd chuckled at this idea. My husband and I, our grown children, my extended family members (and a few very conscientious friends), all of whom are not children of the Depression, do the same. We do it to reduce our use of plastic. In a perfect world in my own home, I wouldn’t own a zip-lock bad, but alas, I’m far from perfect and the few remaining plastic bags that came new in a box from the grocery store, are living their more than nine lives in my home. Thanks, Jimmy, for doing your small and very big part for our ailing planet. And thank you, Jason, for your beautiful writing.

What a beautiful essay, thank you. As a Brit, I had no idea of Jimmy Carter’s environmental credentials. I only remember Reagan coming in and joining with Maggie Thatcher to wreak havoc on our nations. But, as I heard recently on The Rest is History podcast, it seems even these key figures can only be described as symptoms of broader changes in society, rather than the only and direct causes. It has helped me to reframe my perspective of societal change away from the idea that ‘great men’ instigate it (although Carter does sound like a leader with great qualities), to the idea that there has always been change in the world, progressive then counter-progressive, ebbs and flows. Which we choose to align ourselves to, matters, of course. But I have faith that we will find our way back through this current darkness. Focus on the light, I tell myself, the countless people doing wonderful things for nature every day, not the few who want to tear it apart. Your Substack is one such example of someone who cares, and there are many, many of us. The thought just about keeps me sane at the moment 😏