Breaking Boundaries

1/27/22

Hello everyone:

Please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to peruse the curated Anthropocene news items.

Here’s this week’s essay.

Consider for a moment the story of Adam and Johanna, two musicians-turned-farmers who have been living their dream here in Maine. They own Songbird Farm in Unity, a town that lies at the heart of the progressive farm movement in a state that does more than perhaps any other to attract, train, and support young farmers. They purchased their farm in 2014 with help from Maine Farmland Trust, and they live and work just a few miles from the fairgrounds where MOFGA, the Maine Organic Farmers and Growers Association, hosts its beloved annual Common Ground Fair. In 2021 Johanna and Adam grew four acres of organic vegetables and about forty acres of organic heirloom grains. Some of their fields are leased from the local land trust. The produce is sold through co-ops and farmers’ markets and through a direct-to-consumer share program.

Over the last several years, Johanna and Adam have woven themselves into the farm, its land, and its community of species. They’ve chosen to live a life of hard work and good actions. With their young son they’re also knit into the Unity community, into the community of organic farmers, and into the lives of the customers who believe in their mission of farming more responsibly and sustainably.

Developing a farm, and a farm business, takes time. Two years after the purchase, they told Maine Farmland Trust (in a profile on the MFT website) that

We have a sense of what to expect from the soil and the micro climate, but we’re also just getting to know the place. The exciting thing… is knowing that we can build that local knowledge for years and develop our business to reflect the strengths of this spot. We like how the fields slope gently to the southwest, how soil retains water during a dry spell, and how the breeze blows most of the blackflies away. Also, we get pretty awesome sunsets.

We love farming because we get to work hard, spend most of our day outside, and most importantly, because we get to produce something so simple, and also so fundamental, as good food.

The land, for this new generation of progressive farmers, has a meaning that is at once deeply personal, communal, and historical. Adam and Johanna note on their website that they’re conscious that the land they farm is still Wabanaki Confederacy/Abenaki land, and so they contribute some of their profits to Wabanaki Reach.

All of which means that Johanna and Adam are the kind of folks who try to live with a bright awareness of who they are, where they are, and what they’re doing.

But the land held a secret. Several weeks ago, Johanna and Adam learned that their farm is severely contaminated with PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances), a class of “forever chemicals” that bioaccumulate and threaten human and environmental health. Their well water tested at 400 times the state’s safe threshold.

Suddenly everything, everything around them was not what it had been. The earth was suspect; the water was suspect. The food in the pantry they’d stored and preserved for the year seemed more threat than promise. The food they’d sold and were planning to sell might be more liability than asset. Their relationship with their customers was at risk. The home and farm they’d put five years’ labor into was at risk. Their child, nurtured on organic homegrown food, was at risk. Everything was heartbreaking.

In the early 1990s, a quarter century before Adam and Johanna purchased the farm, the land had been fertilized with municipal “bio-solids” (a euphemism for septic waste). Because some PFAS can take an estimated 1000 years to break down in soil, and because they can take 8 years to clear out of our bodies, and because our bodies are constantly exposed to more PFAS in a myriad of ways every day, the chemicals accumulate over time.

How dangerous are PFAS? Two answers: 1) very dangerous, and 2) we don’t know. According even to the EPA, an often-hamstrung agency notoriously slow to regulate industry, the few PFAS that have been studied with any depth are linked to an awful litany of health problems:

Current peer-reviewed scientific studies have shown that exposure to certain levels of PFAS may lead to:

Reproductive effects such as decreased fertility or increased high blood pressure in pregnant women.

Developmental effects or delays in children, including low birth weight, accelerated puberty, bone variations, or behavioral changes.

Increased risk of some cancers, including prostate, kidney, and testicular cancers.

Reduced ability of the body’s immune system to fight infections, including reduced vaccine response.

Interference with the body’s natural hormones.

Increased cholesterol levels and/or risk of obesity.

But the vast majority of the hundreds of thousands of chemicals manufactured for use in human society are not tested for their toxicity to life. PFAS are a notorious example; there are over 9,000 variations of PFAS chemistry, and very few have been rigorously examined.

Why? The chemical industry has been a runaway train since the 1800s – running on parallel tracks next to the petroleum industry, from which it sources many of its base chemicals – but since the middle of the 20th century in particular its products have been racing headlong through every home and community on Earth. The industry has been allowed, generation after generation, to contaminate human and natural environments because its benefits to consumers allegedly outweigh the costs to society. This is, to be clear, merely an industrial version of the Machiavellian principle of the ends justifying the means.

In the U.S., the regulatory structure is backward and irrational. The 1976 Toxic Substances Control Act, for example, allows the EPA to require testing for chemicals only when it’s been provided evidence of potential harm. Which means that the chemical companies mostly “regulate” themselves, and that life in a world shaped by modern chemistry is a “buyer beware” environment, because chemicals sold to us (either directly or hidden in other products) are considered innocent until proven otherwise. Proof is often difficult, though, despite the cancers or other mysterious illnesses, the years of lawsuits, and the activists in marginalized communities where the industries are often located. The chemical industry thrives because it is poorly regulated, and because of the doubts inherent in ascribing cause-and-affect when we (and our environments) have been slowly poisoned over decades from multiple invisible sources.

Like dark matter, PFAS are ubiquitous. They’re in nonstick pans, firefighting foam, grease-resistant food and fast-food wrappers, cosmetics, clothing, furniture, carpets, cleaning products, paints, and countless manufacturing processes. (That’s a very limited list.) And because PFAS are ubiquitous in the fabric of society, and because this vast class of chemicals does not break down easily in the body or in ecosystems, every one of you reading this has PFAS in your body. Everybody you know is also carrying PFAS in their cells. The Environmental Working Group reported in 2019 that according to unreleased federal data 110 million Americans may have PFAS in their drinking water. Innumerable industrial sites and over 700 military bases are badly contaminated. Any neighborhood or business district that has had structural fires has also had PFAS-laden foam soaked into their soils and leached into their water table. (I was afraid to look this up, but I’m glad I did: Apparently the fire retardants sprayed on the wildfires coming to define certain Anthropocene landscapes don’t often contain these chemicals.)

As John Oliver of Last Week Tonight outlined in one of his excellent, absurd-yet-poignant investigative monologues, when PFAS manufacturer 3M tried in the 1970s to set up a control group of test subjects who were PFAS-free, they couldn’t find them. Anywhere. An activist interviewed for the Last Week Tonight piece explained:

There was no clean blood. They tested kids, they tested adults, they went to Asia, they went all over the world and everywhere they looked, practically, they found their chemicals in people’s blood. Eventually, they did find some clean blood. It turned out it was the blood that had been taken from army recruits and archived, saved, at the start of the Korean War.

3M had to go back to the 1950s, before PFAS spread like an unchecked virus. But 3M’s cute experimental dilemma is our real-world dilemma. “There is no longer any population or place on earth untouched by PFAS contamination,” as a recent Guardian article put it: “We are living through a toxic experiment with no control group.”

For a deeper dive into the 3M/PFAS story, check out this long investigative report from The Intercept, which explains among other things that 3M knew as early as the 1970s that their PFAS chemicals were both toxic and likely to bioaccumulate. For a shorter but excellent primer on PFAS you can read this explainer article here from the PFAS-Free Project in the UK.

Maine has established a moratorium on the land application of biosolids, but it is the only state to do so and there are loopholes (Adam and Johanna recently testified in support of a bill that would close those loopholes). The biosolids that contaminated what is now Songbird Farm are still commonly applied as fertilizer on U.S. farmland today, despite the likely presence of heavy metals, PFAS and thousands of other chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and more. A quick online search on biosolids as farm fertilizer brings up multiple state agriculture department sites explaining the benefits of a plentiful, cheap fertilizer, one that in many cases can help a farmer use less petroleum-based fertilizer. Likewise, home gardeners may well be using biosolids-based compost without knowing it, and without knowing that they’re applying an accumulating dose of PFAS to their gardens each year.

All of which is to say that the ground that Adam and Johanna are standing on is the same ground we are all standing on. We live in an era in which even the best environmental ethics can still be undermined by the air we breathe, the water we drink, or the food we eat, because in the Anthropocene our air, water, earth, and fellow species have served not as a commons protected for all but as resources to be extracted, monetized, and discarded. And now we live in a period in which we have broken through the boundaries of many of the planetary systems that have nurtured our species and the millions of others that share this time on Earth.

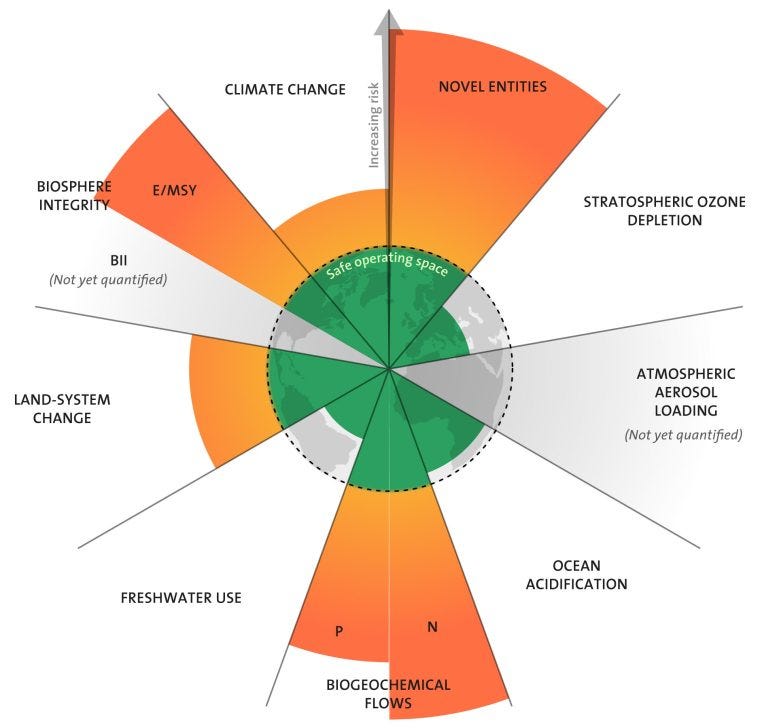

This is a map of those broken boundaries. The Stockholm Resiliency Centre (SRC), “an international research centre on resilience and sustainability science” and a joint initiative between Stockholm University and the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, composed a list of the nine planetary processes that “regulate the stability and resilience of the Earth system” and devised the graphic to represent the data on how each of these boundaries is faring. The green inner circle is the “safe operating space,” while the yellow represents the zone of increasing risk and the orange warns us that we’re well beyond the zone of uncertain risk and into real trouble. As an image, perhaps its key message is that we must discard the harmful fiction that the resources civilization relies on are limitless. In fact, it says, we’ve blown past some of the limits already.

Each category deserves multiple essays… but I’ll mention them briefly here and conclude with the most recent news – and most relevant to Adam and Johanna – from the SRC. The good(-ish) news is in three categories: Ozone Depletion, which is more or less under control; Freshwater Use, which is really a location-dependent good-news/bad-news story; and Ocean Acidification, which short of a near-term miracle is headed for yellow and orange. Atmospheric Aerosols (airborne pollution impacting weather and climate) haven’t been quantified yet, nor has the biodiversity loss side (BII) of Biosphere Integrity. The extinction rate side, shown here as E/MSY (extinctions per million species-years), has been quantified, and it’s not pretty. Climate Change, of course, and Land-System Change (that’s the majority of the planet shifted to human purposes), are in the orange, while Biogeochemical Processes, split into P (phosphorus) and N (Nitrogen), are nearly off the chart because of the extraordinary amount of fertilizer we create from fossil fuels. Finally, there’s Novel Entities (“toxic and long-lived substances such as synthetic organic pollutants, heavy metal compounds and radioactive materials”), quantified now for the first time and understood to be headed for red. Here’s how an article at SciTechDaily summarized the Novel Entities situation:

There are an estimated 350,000 different types of manufactured chemicals on the global market. These include plastics, pesticides, industrial chemicals, chemicals in consumer products, antibiotics, and other pharmaceuticals. These are all wholly novel entities, created by human activities with largely unknown effects on the Earth system. Significant volumes of these novel entities enter the environment each year.

“Significant volumes” is an understatement, or a euphemism, given that the mass of human plastic production alone now surpasses the mass of all life on Earth. The impacts of all these chemicals, not to mention the completely unknown effects of these chemicals in combination, cannot be overstated. Across the planet, throughout ecosystems, there are problems with toxification, fertility reduction, genetic damage, and subsequent population decline.

If you want to know what breaking planetary boundaries looks like at a local level, the fate of Songbird Farm is a pretty good place to start. There are millions of others stories you could start with – that’s the nature of the Anthropocene, an era defined by geologic-scale interference in Earth systems – but while thinking about the Songbird story you can see the SRC graphic’s orange wave of “novel entities” pushing far out beyond the planet’s safe operating space. You don’t have to imagine great oceanic garbage patches, or try to make a picture out of the plastic industry’s plan to triple production in the next few decades, or even try to count the 9,000 plus chemicals under the PFAS toxic umbrella. You only need to look around.

We can feel the excess – the boundaries broken – in every supermarket aisle. Imagine the single-purpose industries that replaced rich ecologies, the multi-continental journeys, and the expended energy for each of the ingredients, for the plastic packaging, for the refrigerated flesh. Our markets burst at the seams while ecosystems grow threadbare at the source. Part of what’s heartbreaking at Songbird Farm is that Johanna and Adam are particularly motivated to provide healthy food from well-treated land as a means to reduce the unhealthy, unsustainable excess of our path to broken boundaries.

The good news at Songbird Farm is that so far all tests indicate that the grains they grow (wheat, rye, oats, and flint corn) don’t seem to pull PFAS from the soil. Those products from the farm are still on the shelf. Also, Adam and Johanna have an extensive web of support from family, friends, neighbors, MOFGA, and Maine Farmland Trust, and are so far getting a strong active response from state agencies. You can read their open and honest PFAS statement on their farm website.

One way forward through this era of hidden toxins, industrial privilege, and often reluctant government oversight is to provide a right for every citizen to clean air, clean water, and a healthy environment. We tend to think that we have such a right, but we do not. Only PA, MT, and recently NY have established anything like a permanent environmental right for their citizens, a right written directly into the state’s bill of rights alongside freedom of speech and the free practice of religion. In PA, the amendment to their constitution was used successfully several years ago to defeat a clot of bills that gave the fracking industry a free pass to profit off of environmental contamination and societal harm.

There is a very active Green Amendment movement to expand this right into every state; several states are in the midst of it as I write this. Here in Maine it’s known as the Pine Tree Amendment, and the bill, LD 489, has passed out of committee with bipartisan support and is headed for a vote very soon before the full legislature. A two-thirds vote is required to pass a constitutional amendment, so we need all hands on deck.

Maine residents reading this can help, right now, by signing the “Sector Letters.” (I helped write a few of these.) Are you a grandparent, business owner, farmer, student, healthcare worker, artist, scientist, or outdoor enthusiast? There are many other letters as well. Click the Sector Letter link and see which letters fit your description. Every letter you sign will be sent to every Maine legislator ahead of the vote. The Pine Tree Amendment isn’t a partisan issue; a healthy environment is good for people and good for business. Please read up on the amendment and sign some letters. Imagine a future in which our right to clean air, clean water, and a healthy environment is part of the foundation of society.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In curated Anthropocene news:

Visualizing deforestation and reforestation: Want to see how the world’s forest cover has waxed and waned (mostly waned) over the last 30 years?

China’s near-zero population growth: Good news, though no one seems to think so.

Evangelical environmentalism: Something the planet desperately needs. Here’s an interview with Katherine Hayhoe, a climate scientist, the Chief Scientist at the Nature Conservancy, and an evangelical.

A primer on degrowth, that strategy to detox and detach the economy from its zero-sum game with the natural world, from Mother Jones.

Hi everyone:

Here's a quick update/addition to Johanna and Adam's story. Because of their testimony before a legislative committee on a bill that would close loopholes in the ban on spreading wastewater sludge, the media has picked up on their PFAS story. Two notes I'd like to add: First, the family's blood was tested and "those tests found levels of PFAS 250 times higher than the average person." And second, that the previous owner of the organic farm "retired after a cancer diagnosis to spend more time with his family." Of course, we don't know if that cancer diagnosis was related to the farm. (Both quotes from https://www.centralmaine.com/2022/01/26/unity-organic-farm-pulls-products-after-tests-reveal-high-levels-of-forever-chemicals/)

The PFAS story, particularly as it relates to food production here in Maine and around the country/world, will become far, far larger than it currently is. How can it not? These chemicals are mass-produced and ubiquitous in our lives; the industry has so far enjoyed an impunity it does not deserve; and regulation is in its infancy. Stay tuned.

Ugh. I guessed what was coming after I read your first sentence. If you weren't such a good writer, I wouldn't have been able to get through this post. Thank you, keep shining that light of yours!