Hello everyone:

Here’s what I have this week in curated Anthropocene news:

Be Naturalized, Not Invasive: From Yes! magazine, a fine 2019 article from an ecologist talking about how to reconcile our role as an invasive species. There are models around us we can follow: plants which followed us around the world but which serve the ecosystems they join. We cannot become indigenous, but we can act in ways which parallel indigenous values. We can, in effect, become naturalized citizens of the places we have colonized.

Time to Pay Up: From the New York Times, a recent article detailing the squabble over an Interior Department report on drilling for oil and gas on public lands. The good news is that the report recommends energy companies should face a rate hike in the royalties they pay for siphoning billions of dollars out of the commons. The bad news is that there hasn’t been an increase in fees since 1920. The worse news is that the report is silent about the climate and environmental impacts of energy extraction on public lands. Absent that kind of basic narrative from the government, there’s little chance the Biden administration is working toward its professed long-term goal of eliminating drilling on public lands.

Mine, Mine, Mine: Two-thirds of the world’s cobalt, the “blood diamond of batteries,” comes from the Democratic Republic of Congo. The New York Times has done a three-part series on how Congo is at the center of the electric revolution’s resource struggle, how China came to dominate Congo’s cobalt industry, and how the political tussle in Congo isn’t helping the often inhumane working conditions for small-scale miners.

Now on to this week’s essay. This is a continuation of last week’s writing on the havoc caused by our obsession with economic growth, so new readers might want to look at that first:

For many observers, economics in the Anthropocene isn’t a sideshow. It’s the show. National and international economies are structured around the devouring of resources for the purpose of supporting the constant growth of GDP. As that growth continued, exponentially, through the 20th century and the first part of the 21st, the devouring has raced well past sustainable levels.

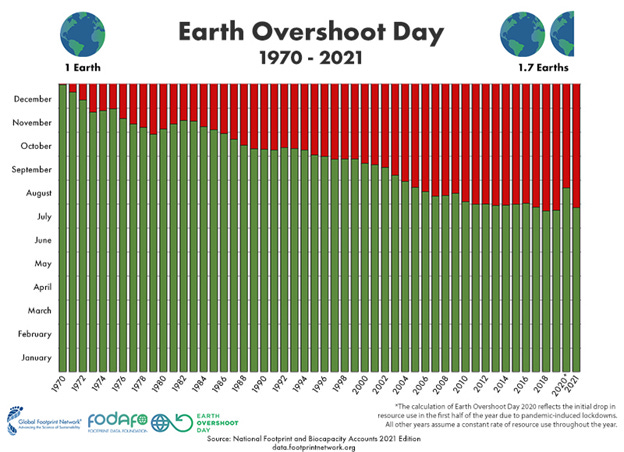

One useful, if disturbing, measure of this excess is Overshoot Day, which “marks the date when humanity’s demand for ecological resources and services in a given year exceeds what Earth can regenerate in that year. In 2021, it fell on July 29.” That means that every day since July 30th we’ve been breaking the Earth’s ecological budget. It’s estimated that the first Overshoot Day was back around 1970, as this chart indicates. Note the current consumption rate of 1.7 Earths per year in the upper right corner:

For fifty years, then, we’ve been living deep in the red, which we might imagine as borrowing too many ecosystems, plants, animals, fossil fuels, and minerals than we can pay back. Which would be a cute analogy if the debt we’re incurring weren’t existential. So when you hear that we’re slipping toward a mass extinction event, or that the oceans are 30% more acidic than preindustrial levels, or that manufactured plastics now outweigh all land and sea animals combined, you can see these macro-phenomena as consequences of the macroeconomic fantasy known as uncontrolled constant growth.

Usually an environmentalist conversation about economics tilts toward Wall Street greed, selfish CEOs and shareholders, or what President Rutherford B. Hayes called “a government of corporations, by corporations, and for corporations” back in 1922. These are valid targets, but remember these entities take their cues from a global culture which permits and encourages the excess devouring that results from constant growth.

I’ll risk a metaphor here, one that, in the context of the Anthropocene, deserves greater exploration another day: The Lucifer Effect, a term coined by psychologist Philip Zimbardo to explain how ordinary, reasonable people will often do terrible things when under strict guidance to accomplish an ideological goal no matter the cost. Get information from the prisoner. I don’t care what it takes!… Or The cult is your only friend; abandon your family!... Or The election was stolen; you know what to do!

We have a tendency to hand over our moral compass to authority under such circumstances. Zimbardo ran the infamous Stanford Prison Experiment, and many years later acted as a witness for the defense of a U.S. soldier on trial for atrocities at the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. My ugly metaphor is meant to suggest that a century of unrestrained growth has long bred and sustained a set of cultural values in pursuit of growth that has abstracted us from the natural world. Call it a global cult serving, if not worshipping, constant growth. It’s not a particularly radical analysis, but my point is that the world is full of good soldiers serving a corrupt idea because there’s no real alternative. We all play by the rules we’re given.

That said, a market is just a market, it seems to me, until two questions about it are answered: With what intensity does it operate, and what end does it serve? Preindustrial markets served up goods and services derived wholly from natural sources, but back then our population was less than one billion and we hadn’t begun the fossil fuel revolution which acted as a force multiplier for population growth and the desire to accumulate capital. If we were to change the rules of the game, i.e. mandate that the purpose of markets is to create benefits for both human and ecological communities, and if we were able to maintain sustainable population and consumption levels, then the market would not be the problem.

Socialists and capitalists – you know who you are – feel free to chime in here. I’m aware that I’ve barely skimmed the surface in this discussion. In the interest of brevity, however, I’m going to move on to the debate over what our relationship to growth should look like for the foreseeable future.

I’ll start by briefly looking backwards, though. The economist largely responsible for our modern concept of GDP, Simon Kuznets, warned Congress in 1934 against imagining it as a holistic economic metric. It is, he said, an illusion to think that the hard number at the end of the equation actually represents a precise accounting of a real-world economy: “The welfare of a nation can, therefore, scarcely be inferred from a measurement of national income…” Thirty years later, Kuznets was still making this point, if a bit more bluntly: “Distinctions must be kept in mind between quantity and quality of growth, between costs and returns, and between the short and long run. Goals for more growth should specify more growth of what and for what.”

Which brings me to “green growth” (a.k.a. “post-environmentalism”) and the ecomodernists. The 2015 Ecomodernist Manifesto (yes, there’s a manifesto, a rare thing these days) from the Breakthrough Institute attempted to upend environmentalism by defending the power of economic growth to solve its own problems. To be clear, these are not ExxonMobil or Wall Street flacks, but eighteen ecologists, environmental economists, and academics focused on solving social and environmental crises. Here’s their basic proposition:

[W]e write with the conviction that knowledge and technology, applied with wisdom, might allow for a good, or even great, Anthropocene. A good Anthropocene demands that humans use their growing social, economic, and technological powers to make life better for people, stabilize the climate, and protect the natural world. In this, we affirm one long-standing environmental ideal, that humanity must shrink its impacts on the environment to make more room for nature, while we reject another, that human societies must harmonize with nature to avoid economic and ecological collapse.

This sounds lovely, and I like that they understand the Anthropocene is permanent but malleable, but it’s their last point that gets interesting as we dig into it. “Harmonizing with nature” in this context means living within ecological bounds. The ecomodernists don’t think those bounds exist for us.

How is it, they ask rhetorically, “that people are doing so much damage to natural systems without doing more harm to themselves?” The obvious answer, to me at least, is a combination of Of course we’re doing extraordinary harm to ourselves, from anxiety to air pollution to pandemics and It’s about to get a hell of a lot worse if we don’t act quickly. Their answer, though, is that our wisdom, knowledge, and especially technology will accelerate “decoupling” and “dematerializing” to make a growth economy so efficient that it will improve equity in human society and give nature room to regenerate. Thus the “great Anthropocene.” I know the terms decoupling and dematerializing sound like they’re borrowed from the language of Goop and Star Trek, respectively, but they describe economic growth which decreases pressure on the environment (decoupling) by decreasing our use of resources (dematerializing).

Here’s another rhetorical question cited in an ecomodernist essay: “Robert Solow, a Nobel laureate… asked, ‘Why shouldn't the productivity of most natural resources rise more or less steadily through time, like the productivity of labor?’” Well, I’m not an economist, but it seems to me that labor is an action which can be improved, while resources like, say, phosphorus, are materials in finite quantities. Even if Solow means that we’ll continue learning to do more with less, those efficiencies have been, and will continue to be, erased by growth in population and per person consumption.

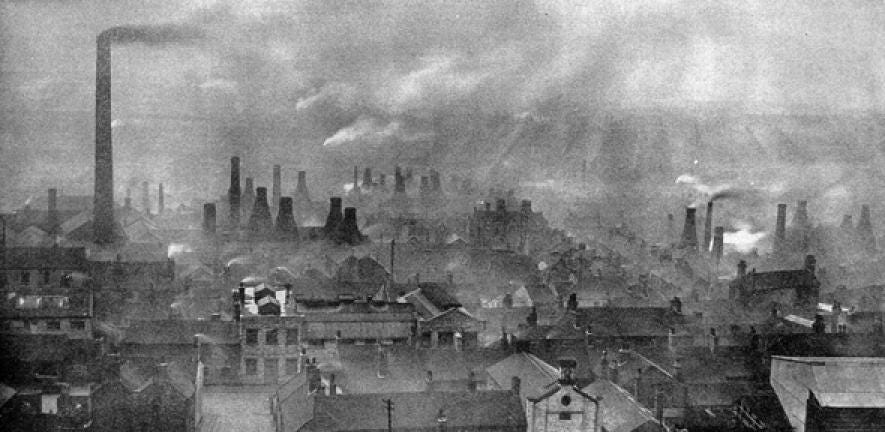

It’s long been known that increases in efficiency tend to lead to increased, not decreased, consumption. If something - sugar, fuel, technology - becomes cheaper we use more of it, not less. Thus efficiency fails to remain efficient. This is called the “Jevons paradox” in economics, named after a British economist who figured this out in 1865, back when coal was king of the Anthropocene. The cheaper coal became, the more of it was burned.

The makers of manifestos, it should be said, have usually been better at asking questions than providing answers.

It’s not that ecomodernist thinking is without merit. These are brilliant folks at the Breakthrough Institute dedicated to improving human lives and environmental outcomes. (Their site is fascinating, if read with caution.) There is evidence of large-scale decoupling, especially of CO2 emissions from GDP growth. Most of the evidence, though, is on a smaller scale, as when more efficient electronics and appliances reduce energy use per device. The bigger problem is that the bulk of decoupling is relative rather than absolute; that is, we’ve innovated efficiencies but because of growth in population and individual consumption we’re still using more energy and more resources every year. GDP growth continues to increase ecological harm.

In the end, perhaps the best argument for green growth is that it requires less civilizational transformation, which means it’s that much easier to sell to economists, corporations, politicians, and citizens alike. As one critical assessment put it,

despite its flaws, post-environmentalism can hold considerable sway because its politics align with powerful interests who benefit from arguing that accelerating capitalist modernization will save the environment.

But green growth’s flaws are likely fatal. A 2020 review of 179 papers on decoupling published over 30 years found “no evidence of the kind of decoupling needed for ecological sustainability.” Worse, the authors concluded that “in the absence of robust evidence, the goal of decoupling rests partly on faith.” Ouch. That’s as close to an insult as you can find in scientific literature. And it’s an echo of the opening lines in a 2009 report, “Prosperity Without Growth,” of the UK government’s Sustainable Development Commission: “Every society clings to a myth by which it lives. Ours is the myth of economic growth.”

Time is certainly working against the ecomodernists. Even if decoupling and dematerializing were happening in a meaningful way – which they aren’t – the 21st century’s acceleration in extinctions, climate disruption, etc., won’t wait for innovation to somehow magically eliminate the harm of an exponentially-growing economy. Global consumption continues to increase. We dig more stuff out of the Earth than we ever have, particularly for the industries looking to feed materials into the electrification of everything. Agricultural takeover of biodiverse land is still spreading, even with recent efforts to make farming more Earth-friendly. (Herbicide use has increased dramatically as well.) We’re increasing our population at 2.4 babies per second, a million every five days, 81 million per year. (Weirdly, the ecomodernists don’t think population growth is a problem. My recent essay on carrying capacity cited a skeptical founder of the Breakthrough Institute.) I appreciate their optimism – their “angelizing GDP,” as one critic described it – but doubling down on the Anthropocene seems like misplaced faith.

The optimistic high ground they’ve tried to claim – We can do this! – feels to me more like a pessimism regarding our ability to make the necessary systemic changes. It’s a dangerous optimism too, because it encourages us to keep digging our way out of our Anthropocene hole, even as Overshoot Day arrives earlier every year. But then again, optimism that the benefits of constant growth outweigh its costs has always accompanied the myth. Or as Greta Thunberg put it to UN delegates at a climate summit, “We are in the beginning of a mass extinction, and all you can talk about is money and fairy tales of eternal economic growth.”

Like Greta, I’m getting tired of money and fairy tales. I’d really like to get back to writing about the real world. I feel obligated, though, to finish this economic journey next week with a dive into two proposals for an alternative global economy. Because they’re theoretical, I hesitate to call them solutions, but that is certainly their intent. A steady-state economy requires stability in population and consumption, and aims for sustainability in resource use. Degrowth is about not merely stabilizing, but shrinking the global economy until civilization fits neatly into the nest that nurtured us.

Stay tuned.

Great work Jason.

Much of the "environmentalism" I see promotes consumption and growth.

- Electric cars are marketed as a solution to greenhouse gases, but are really meant to allow us to continue driving without restrictions.

- I heard an a on Maine Public Broadcasting the other day for a credit card that plants trees based on how much you spend.

- Many environmental organizations raise money through catalogs of "environmental gifts" that you can buy.

We need to get away from the idea that we can consume wastefully in ways that help the environment.

No better way to set the hook in me than referencing green growth and the Stanford prison experiment in the same essay. Though we can argue how much agency one has in a coercive market system :) Relatedly, a certain German philosopher has something to say about the “tendency of the rate of profit to fall”, which explains the link between GDP growth mania and Jevon’s paradox.

Beyond GDP, are you familiar with Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness index? A nice idea.