Heat and the Hydrosphere

9/8/22 – Some notes on the current spate of epic droughts, heat waves, and floods

Hello everyone:

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read some important and interesting curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

I don’t often build my weekly essay around news headlines, but I’ll make an exception this week to make a few points about the turbulent state of the hydrosphere. A third of Pakistan has been underwater. That’s one third of a country twice the size of California but with nearly 100 million more people than the entire United States. Monsoon rainfall there is 780% higher than normal. The scale of loss and damage is staggering. Just this year, floods in Europe, central Appalachia (9 inches of rain in 12 hours!), eastern Australia, Iran, Sierra Leone, Uganda, Haiti, and many other places have ravaged communities after unusually heavy rains fell in a short period of time. Death Valley received a year’s worth of rain in a few hours. Floodlist, an excellent comprehensive resource for flood news and commentary, notes that

Threats from sea level rise and increased rainfall, sprawling urbanization and widespread deforestation mean that many countries around the world now experience severe flooding on a regular basis. This is not limited to any particular continent or region.

Elsewhere in the world (and the news), the Colorado River’s Lake Powell, the second-largest reservoir in the U.S. and long a potent symbol of our proud transformation of the west, is at its lowest level since it was filled in the 1960s. Federal authorities have for the first time begun to ration power and water to the 40 million people downstream. The Yangtze (China’s most important river, both traditionally and for 21st century hydropower) and the Rhine (the most important river in Europe) are dangerously low. China is rationing power from Yangtze dams, and parts of the Rhine – a vital cargo route for the region – may soon be closed to shipping. I mention these few rivers as symbols of the hundreds of others throughout the U.S., Asia, and Europe which have also withered.

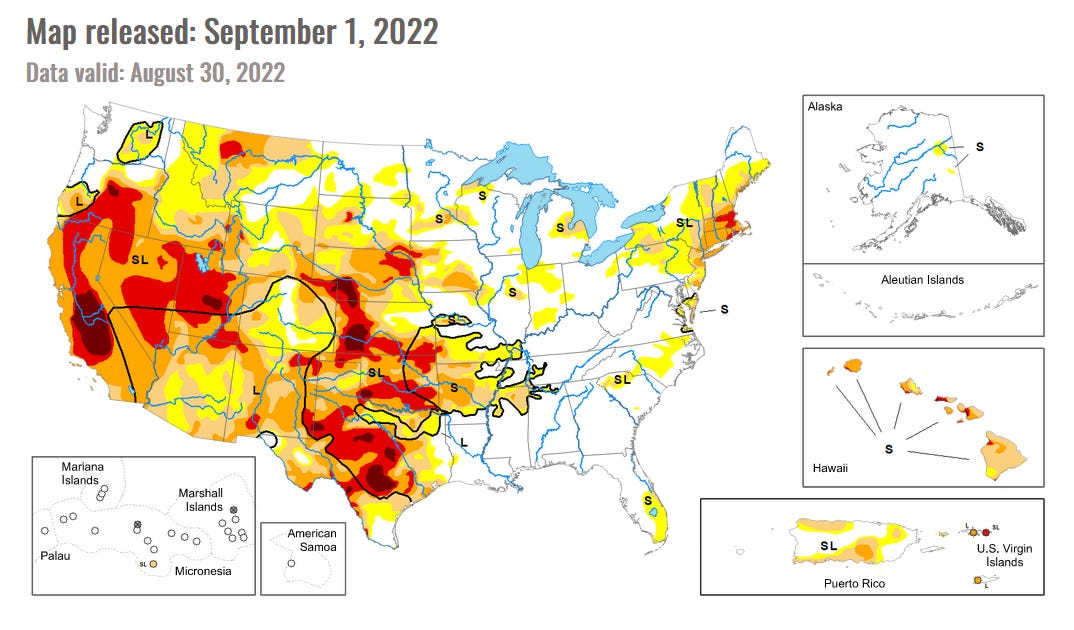

A long-term drought in South America is wreaking havoc with agriculture, particularly in Chile, where the drought is more severe than any in the last 1,000 years. Recent droughts in Australia were deemed to be the worst in the last 800 years, and the government there assumes “It will become more frequent, severe and longer lasting in many regions as the climate changes.” People in the horn of Africa have suffered five straight rainy seasons without rain, and as Bill McKibben notes, “the toll is almost unimaginable. A million people have been internally displaced; the ones who haven’t managed to move to grim camps will soon starve.” The accepted wisdom regarding conditions in the U.S. west is that the current megadrought (over two decades now) is the worst in 1,200 years and seriously exacerbated by our rupture of normal climate patterns. (For a visualization of the U.S. situation, visit the U.S. Drought Monitor and click on the region of the map that interests you.)

Heat waves are becoming more common and more dangerous. India and Pakistan suffered through a long, disturbing heat wave earlier this year in what was called a year without a spring. The highest April temperature ever recorded in the Northern Hemisphere occurred in Pakistan, but that wasn’t the scary part. The heat wave arrived much earlier and lasted much longer than expected. Southeastern China’s heat wave this summer is considered one of the worst in recorded history. Western Canada and the northwest U.S. suffered heat last year that was up to 35 degrees above normal. Records were shattered throughout the region. The event was considered a “1000-year” phenomenon made 150 times more likely by climate change. Last March, at the other end of the planet, warm air flooded over the coldest place on Earth – the East Antarctic ice cap – and broke the record high temperature by an astonishing 85 degrees Fahrenheit. I’ve camped at a standard summer temp of -30°F in East Antarctica and cannot begin to imagine what 55°F would feel like there, and do not want to imagine what it means.

Fires are increasing in frequency and intensity, and fire “season” in some places – like the U.S. west – is now a year-round threat. I wrote a piece last year called “An Age of Fire” on this transformation that the great scholar Stephen Pyne calls the Pyrocene (because the Anthropocene is rooted in our history of burning things). Fires have only worsened since, and that was just a year ago. Fires now behave in ways that veteran firefighters haven’t seen before.

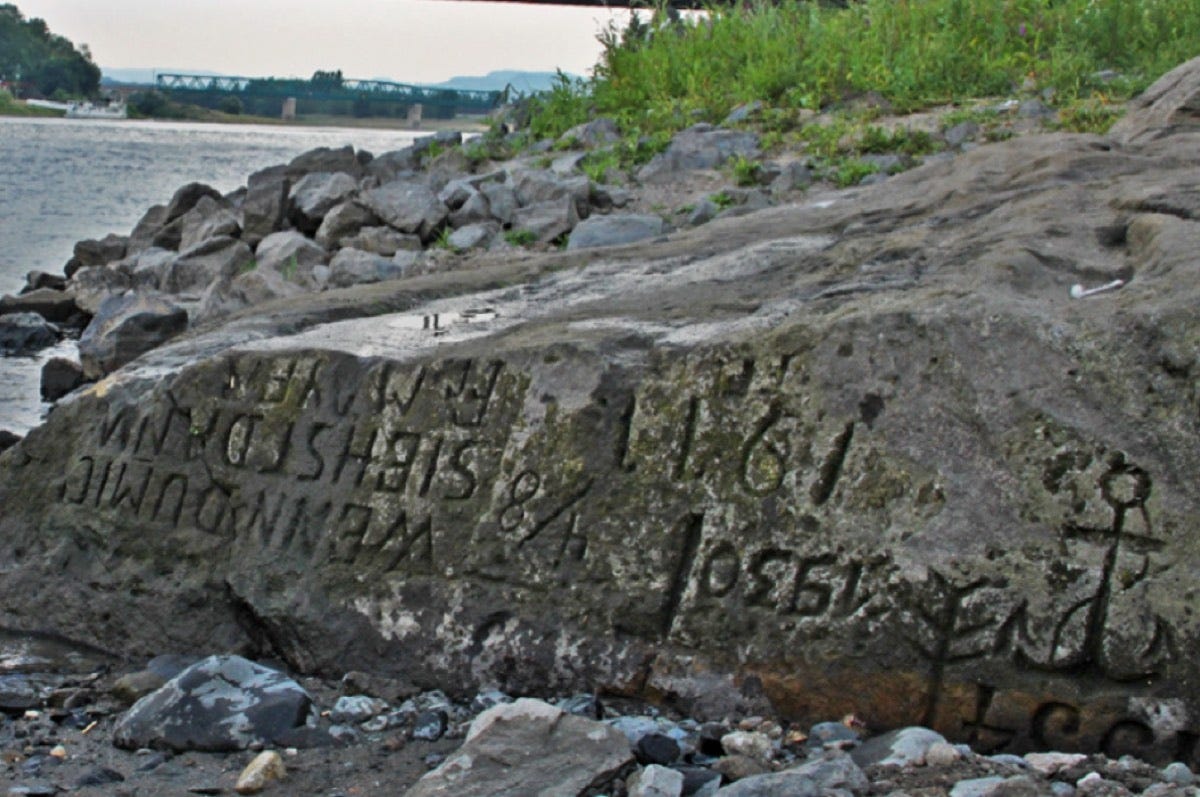

Perhaps the most relevant commentary for all of this is inscribed on a hunger stone revealed in the Elbe River in the Czech Republic: “If you see me, cry.” (For the record, this particular stone is often revealed because of an upstream dam. One more reason to cry, perhaps.) I like to think the writer was enough of a poet to appreciate the irony in asking future sufferers of drought to shed a tear.

I could be making these observations about water scarcity and water abundance simply to ring the now-battered alarm bells about climate change, but those bells are ringing already in our ears. They’re even audible in the halls of government, though not yet loud enough. Instead, I want to make some climate-adjacent points.

First, though, I’ll make the standard weather/climate caveat: Floods, monsoons, droughts, glacial melt, and heat waves are natural phenomena the world over, and weather-related tragedies have been constant companions throughout human history. Pakistan is no stranger to extreme flooding. Megadroughts are woven into the 1,200 years of climate data we have for the western U.S. The unnatural aspects here are the intensity, duration, and frequency. They’re more frequently worse, in other words.

As a recent Axios article put it, “When it rains, it rains harder. When it's hot, it gets hotter and stays that way longer than it used to.” The Rhine, for example, has a history of low water every 20 years or so, but the last time was 4 years ago. So-called “500-year” floods or “1,000-year” storms are happening frequently. All recent evidence points to a worsening around the world on a scale and accelerated timeline beyond our capacity to adapt without widespread suffering. The climate models, as per usual, have underestimated the consequences of our rupture of the Earth’s climatic norms.

Caveat aside, then, here are some things I think are worth considering:

We should admit that thermometers in the Anthropocene now measure suffering as much as temperature. (I think this is pretty well symbolized by Pakistan wracked by a staggering heat wave and then apocalyptic flooding.) As the global average temperature ticks upward by another tenth of a degree, and another, and another, the hydrosphere grows more turbulent.

The dark magic behind these phenomena is intensified evaporation and transpiration, perhaps the least familiar stages of the hydrologic cycle. We think about rain and snow falling, about snow and ice forming, about rivers running, about water seeping below ground, but we don’t often think about how all that water ends up back in the sky to form rain-filled clouds. We don’t see it as easily. Yet in this ever-warmer world, water transpires from plants and evaporates from everywhere else more often and at higher rates. It evaporates from oceans and lakes and rivers. It evaporates from reservoirs needed for hydropower and agriculture and all the other needs of civilization. It evaporates from soil, the source of all terrestrial life, and from wetlands, the source of so much biodiversity. It transpires from plants and forests, which makes them thirstier for moisture from the drier soil. Average rainfall in a hotter climate isn’t enough to satisfy the plants’ needs. More often now, especially for trees, they become weakened by disease, become fodder for invasive insects, and finally become tinder for vast fires.

This is some of the most profound physics of this new Earth: warmer air holds more moisture. The more we heat the atmosphere, the more water vapor it will hold. As Bill McKibben put it, “Warm air holds more water vapor than cold, and from that the main events of post-modern twenty first century will descend.” The “events” he mentions are the ones that this year have descended upon and drowned Pakistanis, Kentuckians, Ugandans, Chinese, and so many more. But the increased water vapor doesn’t accumulate in the atmosphere. In fact, it only stays aloft for an average of nine days.

Which is why we’re getting worse floods and heat waves at the same time. The global rates of evaporation and precipitation have both increased. Water vapor going up in the brutal heat over Sichuan Province came down as catastrophic rains next door in Qinghai Province.

Worse, intense rain and floods are not helpful in ending drought. Brief intense flash floods are no way to store water on the landscape. Parched ground can’t hold water as well, and the run-off disappears downstream. So the increases in evaporation and precipitation often actually increase the likelihood and severity of drought. One of the truisms of this age is that dry places are becoming drier and wet places wetter.

So we live now at the turbulent nexus of heat and the hydrosphere which, for the last ten thousand years or so, had existed in a nice balance between water, vapor, and ice. The cryosphere (the icy bits of Earth) is rapidly shrinking. Sea ice, mountain glaciers, and winter snow packs are disappearing. The Greenland and the West Antarctic ice caps – even the edges of the massive East Antarctic ice cap – are losing ice at rates unprecedented in human history. Which leaves us with more water in the oceans and higher rates of vapor rising in the atmosphere.

I would be remiss if I failed to mention that the intense impacts of a turbulent water cycle can be ascribed to another human attribute. There are so many of us. Our needs and desires and civilizational inefficiencies are so great and becoming greater, and so many of us are living in the wrong places. We occupy flood zones, drained swamps, salt marshes, desert cities, low-lying beach towns, and fire-prone forests. Most of our towns and cities shed water rather than absorb it.

The turbulence in the hydrosphere will beget turbulence in human affairs. This is taking so many forms. In France, nuclear power plants may not be able to cool their reactors with as rivers dry up. Throughout Europe, shipping of essential goods (including coal, ironically) on major rivers is threatened. The 21st century’s planned reliance on hydropower is looking like a real liability, especially in parts of China. Far more importantly, food and water shortages caused or worsened by a hotter, more troublesome climate could be a long-lasting source of political upheaval, just at a time when the world’s nations need cohesion and solid actions to adapt and cope with the turbulent world.

Finally, these events and their worsening trend line are all crises for the natural world too. One image I can’t get out of my head: birds fell from the sky in the south Asian heat wave. Persistent drought and intense floods have numerous impacts on already scarce wetlands and riparian zones. The story of Earth’s remaining forests is being rewritten by fire. Sea level rise may outpace the ability of coastal ecosystems to adapt and shift inland. And so on.

Next time you heat a pot of water for a cup of tea, watch the stages of increasing turbulence. Note how areas of bubbling disturbance persist alongside areas without bubbles, like heat waves alongside flood zones. Then, before the pot comes to a full rolling boil, turn it off. The tea water only needs to be hot enough. Then sit with your tea and think about what you can do to support policies which will turn down the heat globally. It’s hot enough here already.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

From Phys.org, a surprising new finding after a large-scale analysis of Arctic lakes: many are drying up rather than expanding as the region warms four times faster than the rest of the planet.

From The Overpopulation Project, a thoughtful essay by a noted Australian environmental scientist about the need to prioritize family planning as a key tool in the effort to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. “Unless we adopt just and effective approaches to stabilizing the global population and its demands on natural resources,” he says, “it will be impossible to achieve changes at the scale necessary for a civilized future.”

Two good-news stories from Anthropocene: First, an engineering breakthrough in Australia has found a way to use old rubber tires (a billion of which we throw away every year) to make a lighter, “greener” concrete. Second, a meta-study of 150 years of efforts to remove invasive species from islands reveals a surprising result: Most of those anti-invasive efforts have worked. In Palmyra Atoll, for example, the 2011 removal of rats led to an incredible revival of the native ecosystem: “Germination of native plant seedlings increased by more than 5000% and two previously unseen crab species [were] suddenly widespread.”

From PBS NewsHour, a 90-minute special video report on the perilous state of global fishing and the oceans called “Fisheries on the Brink.” This ran back in June, but I’m only now getting around to recommending it.

From Yale e360, not that we needed one, but there’s another threat to agriculture from rising temperatures. High heat is killing more pollen, reducing yields for several important crops, including corn, rice, peanuts, and canola.

Another beautifully written and eloquently explained piece Jason, thank you.

This line struck me particularly hard: ‘We should admit that thermometers in the Anthropocene now measure suffering as much as temperature.’