Here Be Dragons, Part 4

3/10/22 – A Resource for understanding the Planetary Boundaries, completed

Hello everyone:

Two bits of news you can use:

Where to give for Ukraine: Timothy Snyder is a scholar, a professor of history at Yale, and an author of several books on Ukraine, Russia, and the region. He writes a newsletter on Substack called Thinking About… He has provided numerous recommendations for ways to support Ukrainian refugees, the NGOs and other groups who are helping them, and the Ukrainian military, among others. Please check out his lists, starting with the most recent: here, here, here, and here.

A new app, the Substack Reader, for iPhone (not yet for Android): Just in case you prefer to read this Field Guide on your phone…

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read this week’s curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

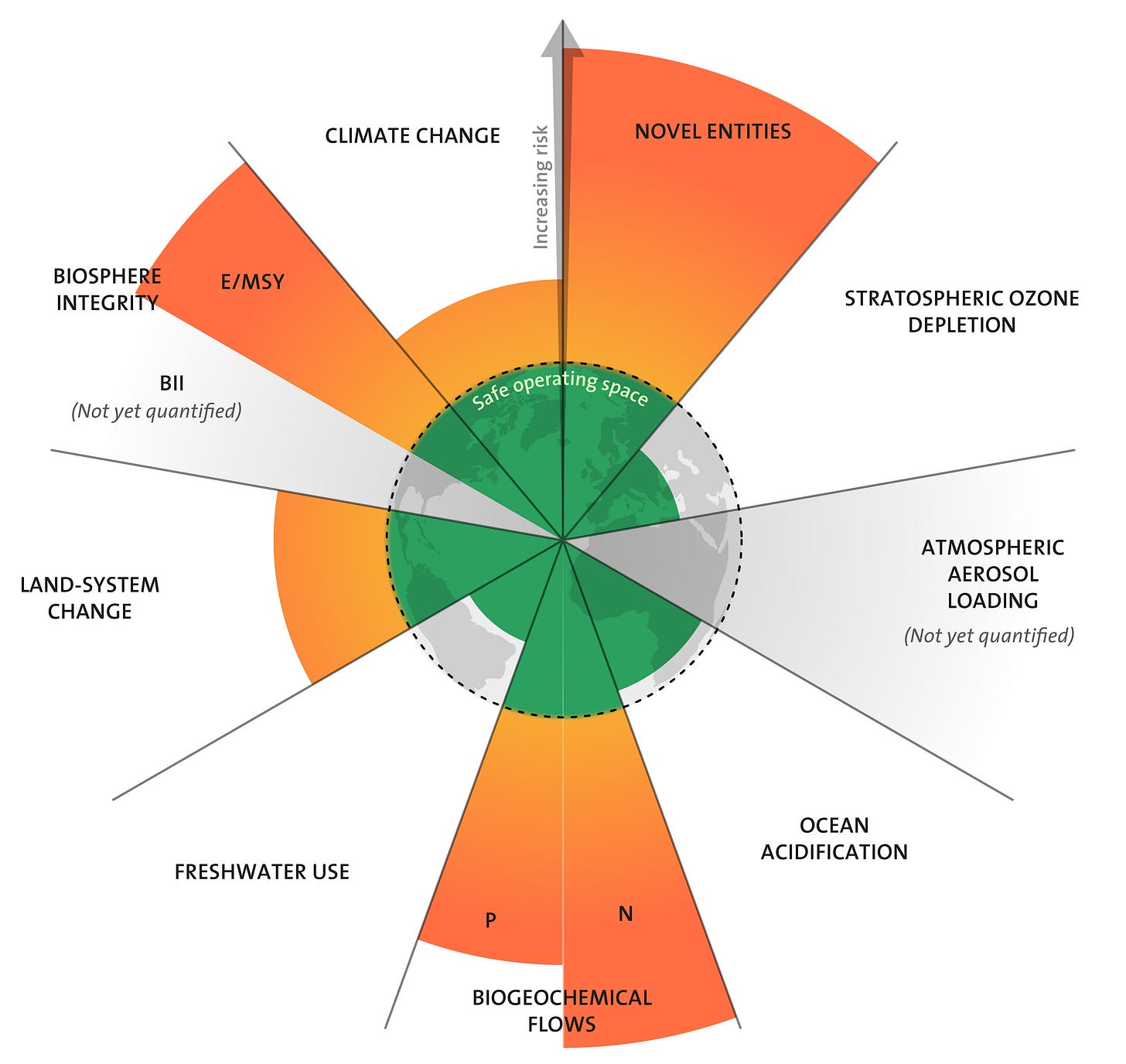

The image above is a profound re-imagining of the planetary boundaries from Kate Raworth at the Doughnut Economics Action Lab. In what she calls “The Doughnut of Social and Planetary Boundaries,” she reminds us that we are tasked with building a more equitable and healthy society at the same time we are compelled to restructure civilization within natural limits. The two are, after all, intimately linked. “Humanity’s 21st century challenge,” she says, “is to meet the needs of all within the means of the planet.”

In other words, to ensure that no one falls short on life’s essentials (from food and housing to healthcare and political voice), while ensuring that collectively we do not overshoot our pressure on Earth’s life-supporting systems, on which we fundamentally depend – such as a stable climate, fertile soils, and a protective ozone layer. The doughnut of social and planetary boundaries is a playfully serious approach to framing that challenge, and it acts as a compass for human progress this century.

In this image, the safe space for humanity and Earth’s living systems is a green ring sandwiched between our two sets of obligations: a Social Foundation and an Ecological Ceiling. The planetary boundaries I’ve been discussing are still depicted as the red overshoot projections outside the green safe space, while on the inside she projects the red shortfalls in our provision of basic social needs for humanity.

I highly recommend you play with the interactive version of this Doughnut at Raworth’s blog. For more information but a little less fun you can explore the work of the Doughnut Economics Action Lab or read Raworth’s paper in The Lancet.

THE BOUNDARIES, continued…

This week is the final installment of a month-long foray into understanding and assessing the planetary boundaries concept as conceived by the Stockholm Resiliency Centre (SRC). Thank you for staying tuned in to what I know is a complex and difficult litany. I sincerely hope that I’ve provided a useful resource for your understanding and further research.

As a reminder, I’ve dug into this challenge because I think that the planetary boundaries concept provides a useful framework for wrapping our heads around the scale of civilization’s to-do list. I initially called it a map, in the hope that it may guide us back to a notion of home where humanity lives with a healthy respect for the constraints of biological and physical reality. But I may prefer the compass metaphor put forward by Kate Raworth. A map, after all, shows us the way, and that’s a tall order. A compass is the tool that guides us across that map, even if we don’t know everything we’ll encounter along the way.

Three weeks ago I introduced and put into context the Planetary Boundaries concept from the Stockholm Resiliency Centre (SRC). Two weeks ago I assessed the two core boundaries (Climate and Biodiversity) and a third, Habitat Destruction/Land-Use. Last week I assessed the boundaries for Ocean Acidification, Novel Entities, and Excess Fertilizer Use. Finally, this week, I’ll finish up with assessments for Freshwater Use, Atmospheric Aerosols, and Ozone Depletion.

Freshwater Use is a boundary that seems straightforward enough. Climate change, excessive human population, our conversion of wetland ecosystems for agriculture, the damming and diverting of rivers, and excessive material consumption in wealthy nations are all putting pressure on the global freshwater cycle. “Human pressure,” says the SRC, “is now the dominant driving force determining the functioning and distribution of global freshwater systems.”

You’ll recall that the freshwater cycle, simply described, has three parts: precipitation falling, surface water flowing, vapor rising. The reality is more complex, with immense reserves of water stored in plants, locked up in polar ice, or hidden away beneath us in groundwater.

Our disturbance of other planetary boundaries is disrupting the cycle in several complex ways. Humans have dammed most of the world’s major rivers, erased 85% of wetlands, and in places (cities, deserts, densely farmed regions) extracted so much water that rivers run dry and groundwater aquifers accumulated over millennia may not last decades. All of this impacts freshwater availability for other species and ecosystems and alters the natural flows of water vapor and cloud formation. But it pales in comparison to the impact from climate change.

A warmer world increases evaporation and atmospheric moisture, intensifies both drought and precipitation, reduces the storage of water as snow and ice, and generally changes climate by introducing chaos into weather patterns. As snowfall decreases and glaciers melt, the nearly 2 billion people who rely on them for drinking water will be at risk. “Water is becoming increasingly scarce,” says the SRC, and “by 2050 about half a billion people are likely to be subject to water-stress, increasing the pressure to intervene in water systems.”

News on this boundary, as with any climate-related boundary, is coming in all the time. A Guardian article just last week noted that new research shows that climate change has intensified the global water cycle twice as fast as feared. But the good news is that freshwater use is still well within the green of the planetary boundary assessment. If we can stabilize the warming climate and human population growth, and diminish the impacts of agriculture on the water cycle, this boundary could remain in the green.

Atmospheric Aerosol Loading is a yet-unquantified boundary concerned with the anthropogenic increase (that’s the “loading”) in airborne particles and pollution that impact climate, weather, and air quality.

The SRC included a boundary on aerosols primarily because of the particles’ influence on the climate system. That influence is complex and includes cloud formation, weather patterns, and changing how much solar radiation is reflected or absorbed in the atmosphere. Some aerosols (e.g. sulfates) scatter solar radiation like mirrors and cool the Earth. We emit so much of these aerosols that their “global dimming” masks about 40% of global warming. Other aerosols, though, like soot from wildfires and dust from disturbed soils, absorb solar heat and increase warming. Meanwhile, scientists have observed shifts in weather systems in particularly polluted environments.

Another reason a boundary for aerosols has been included is their negative impact on biodiversity and human health. About 800,000 people die prematurely each year because they’re breathing polluted air, and it’s reasonable to assume that animal populations are impacted as well. That’s been hard to accurately measure, but it’s clear that aerosols are yet another human impact on both the climate and biodiversity boundaries.

One more thing worth noting here is the story of DMS (dimethylsulfide), a sulfate aerosol, and coral reefs. DMS is naturally produced throughout the oceans, but its impact on climate is still unclear. When coral reefs are stressed from, say, acidification or warming waters, they increase production of DMS, which can then go on to boost local cloud formation. This appears to be a self-regulating system, in which reefs have evolved to try to cool their waters through an increase in cloud cover. Scientists are still working hard to sort out the role DMS may play in a changing climate, but it seems clear that we’re heating the Earth beyond the corals’ capacity for self-protection, and it’s clear that as coral reefs disappear it’s likely that their climate influence will too.

Solutions for the Atmospheric Aerosols boundary sound familiar: Reduce warming, reduce wildfires, reduce agricultural disturbance of soils, and reduce industrial air pollution.

Ozone Depletion is the closest thing we have to a hopeful, good-news story in the assessment of planetary boundaries. And that good news comes in two forms: the unified actions that were taken by the global community, and the results that we can see. Ozone depletion is the only planetary boundary in which we’re moving in the right direction.

I have plans to write an essay or two on the fascinating ozone story, so I’ll keep it short here. But remember this: ozone is an Antarctic story, it’s a remarkable world-comes-together-to-solve-a-problem story, and it’s a story that may serve as potential model solution for the climate and biodiversity crises.

Stratospheric ozone protects the Earth from intense UV radiation. When too much is allowed through, humans suffer from skin cancers and cataracts. More importantly, though, excess UV radiation damages fundamental environmental processes both in the oceans and on land. Life on Earth would be radically altered and diminished without the ozone layer. (Check out this great NASA article, “World Without Ozone.”)

British scientists in Antarctica in the late 1970s noticed that a “hole” in the ozone layer appeared each year over the southern continent, and by the early 1980s it was clear that the main culprits were CFCs, chlorofluorocarbons, the chemicals used in refrigeration, styrofoam production, and aerosol cans. CFCs in the stratosphere react with ozone molecules, removing them from their role in protecting life on Earth. Skin cancer rates in southern nations, like Australia, were increasing rapidly. By the late 1980s, though, nations had gathered to write and sign the Montreal Protocol, which mandated the reduction and eventual elimination of CFCs. This was the most successful environmental agreement in human history.

Johan Rockström of the SRC makes an excellent point in the Planetary Boundaries documentary on Netflix: “This is the first and only example that we can actually manage the whole planet, that we can actually return it to a safe operating space for a planetary boundary that we had seriously taken into the high risk zone.” And David Attenborough concurred: “It was indeed fantastic to witness. Scientists raised the alarm, and the world acted.”

Scientists raised the alarm, and the world acted. We should be so lucky now in the midst of the climate and biodiversity crises. Activists and scientists and government policy makers working on these crises all know the ozone story, and all hope that their conferences and meetings will someday be as successful. Certainly everyone is showing up to the meetings, but among the main challenges they face are a fossil fuel industry far more influential than the manufacturers of CFCs, and a civilizational resistance to the scale of change required in our daily lives to reimagine the energy, food, transportation, and industrial sectors. The solution for CFCs, after all, was fairly painless.

Here’s a really great video account of the ozone story from Vox:

One final note on ozone: According to a very new study, out this week, the slow repair of the ozone layer appears to be hampered by the significant increases in wildfire smoke that climate change is creating. Australia’s “Black Summer” of 2019/2020 sent vast columns of smoke into the stratosphere and set off the same set of ozone-depleting chemical reactions that occur with CFCs.

So, I’m sorry to say, even the good news has a dark lining. But rest assured, the ozone boundary is still heading in the right direction, and still gives us hope that we’re capable of doing the same.

SOME FINAL THOUGHTS

“Just imagine,” says David Attenborough in Breaking Boundaries: The Science of Our Planet, “for the first time since the dawn of humanity, we could wake up one morning on a planet with more wildlife than there was when we went to sleep.” I love Attenborough’s gift for taking the bleakest of facts – we wake each day to a diminished Earth – and creating optimism and opportunity from it. To get to that bright morning, we have a lot to do. And we have to do it with the energy and intention and depth of empathy we’re currently applying to those suffering from the invasion of Ukraine. And we need to do it not for a few months or years but for a few decades, at least.

That is, for the next generation or two we need to reimagine how we – and by “we” I mean first and foremost those of us living in wealthy, wasteful nations – exist in relation to the living Earth. Actually, the reimagining has already been done. We need simply to act on the better ideas (and angels) of our nature. The planetary boundaries concept provides a framework for those ideas.

The utterly irrational notion of constant economic growth has to be left to wither on a shelf in a Museum of Bad Ideas. Or as Johan Rockström of the Stockholm Resiliency Centre put it, “Now it's a question of framing the entire growth model around sustainability and have the planet guide everything we do.” Creating a circular economy – the elimination of waste from the economic system – would dial us back on nearly every boundary: climate, biodiversity, excess fertilizer use (P and N), novel entities, and aerosol pollution.

Within a generation, we need to live in a world that looks back on fossil fuel use the way we now look back on chattel slavery: an abhorrent and grotesque abuse driven by greed and complicity so complete that they impoverished the fate of the world and did not care.

Fossil fuels are at the heart of most of the abuse of the planetary boundaries: climate, ocean acidification, excess fertilizer use, novel entities, and atmospheric aerosols. And they’ve literally fueled to a large degree the astonishing loss in biodiversity and the destruction of habitat. “We’re extracting fossil fuels and using them to make chemicals and pesticides and plastics that are then polluting the world,” says Giulia Carlini, a senior attorney with the Center for International Environmental Law. “There are links between the climate crisis, plastics, biodiversity, and toxics. They are all part of the same story.”

By any rational measure, we are forced at this still early stage of the Anthropocene to apply the precautionary principle in our relations with the natural world, which we have turned into a minefield. Any more missteps and we risk severe impacts that will not be healed within a meaningful human timeframe. Precaution in this context means weighing the possible costs of our actions to biodiversity, the oceans, the climate, etc. Our heedless manufacture of hundreds of thousands of new chemicals, like our heedless extraction of fossil fuels or our heedless erasure of ecosystems must end as we transform our industrial society into one which prioritizes health over wealth.

Large-scale reforestation is essential, as is transforming agriculture into a science which benefits the community of life rather than poisoning and erasing it. Progress on both of these fronts will help rejuvenate the freshwater cycle, provide habitat, and slow biodiversity loss.

I haven’t written much on the benefits of changing our diet, but the impacts can be extensive and vital, as Rockström points out in Breaking Boundaries:

Now the exciting thing is that a diet that is more vegetarian, less red meat, more plant-based protein, more fruit and nuts, less starchy food… if you take that diet and assume that all people would eat healthy food we could actually come back within a safe operating space not only on climate but also on biodiversity, on land, on water, on nitrogen and phosphorus. It's quite exciting that eating healthy food might be the single most important way of contributing to save the planet.

Rockström also believes that the planetary boundaries framework should be integrated into global governance, including at the United Nations Security Council. And that’s part of the hard beauty that drew me to this way of seeing the transformed world. Properly understood and utilized, it offers a path forward for both governments and individuals like you and me.

I’ll leave the final word to David Attenborough:

Thanks to the work of scientists like Johan Rockström, we now have the capacity to act as Earth's conscience, its brain, thinking and acting with one unified purpose to ensure that our planet forever remains healthy and resilient, the perfect home.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In curated Anthropocene news:

From the New Yorker, a long and brilliant article, “The Elephant in the Courtroom,” delving into recent legal activism to provide personhood to intelligent animals.

From The Revelator: Mangrove forests, essential for coastal protection, nurturing young fish, and sequestering carbon, turn out also to be biodiversity hotspots for insects.

From High Country News, an excellent article detailing the energy-sucking costs of our digital lives and the irrational Anthropocene foolishness of cryptocurrency.

From SciTechDaily: Light pollution is impacting the oceans too, as seen in a new atlas.

Does the Earth have a mind of its own? This is an article on a recent philosophical/scientific thought experiment. The assumptions behind the experiment are far too keen on human technology for my taste, but it’s well worth a read.