Hello everyone:

Just a quick story for you this week. Summer is busy in Vacationland, with family visiting.

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read some curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

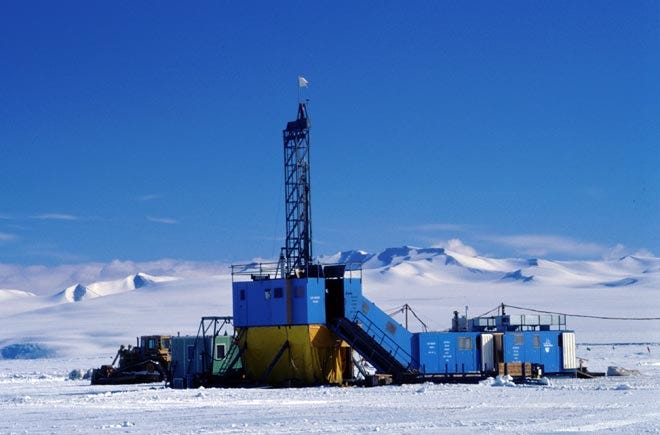

New arrivals to the Field Guide often land on the Welcome Page and find the odd photo you see above. It has no label or explanation. I don’t have an essay for you this week, so I thought I’d take a minute to explain the image before leaving you with a slightly longer-than-usual list of fascinating, difficult, and hopeful Anthropocene stories to follow up on.

Those of you who know me or my writing won’t be surprised to learn that I took the picture in Antarctica, where I worked for most of a decade. In the background are foothills of the Transantarctic Mountains, a 2200 mile-long range longer than the Himalaya and buried neck-deep in glaciers. The Transantarctics divide West and East Antarctica and act as a barrier to the inconceivably large mass of East Antarctic ice, which is up to three miles deep and larger than Australia.

In the foreground are fuel barrels. Many are empty, which is why they’re strapped together to keep an Antarctic gale from blowing them away.

Below the barrels and running all the way to the cliffs in the background is sea ice, specifically about ten feet of ice atop McMurdo Sound in the Ross Sea. The water here is hundreds of feet deep.

What you can’t see in the picture is the reason the barrels are there: to power drilling operations for the remarkable Cape Roberts Project, which brought up thousands of feet of sediment cores (representing tens of millions of years) from the seafloor below McMurdo Sound. Scientists from New Zealand, Australia, Germany, Italy, the U.K., and the U.S. coordinated a multinational and multipurpose operation under risky conditions in order to better understand the geology of the region and the long-term fluctuation of the Antarctic ice sheet. You can read more about it here in an old National Science Foundation publication, but brace yourself for “calcareous nanofossil biostratigraphy and paleoenvironmental history,” “Cretaceous-Paleogene foraminifera,” and “Late Cretaceous-Early Cenozoic drill cores.”

For my purposes here, though, I’ll note that implicit in the ice sheet investigation is the question of how often in the past 100 million years or so global sea levels changed so much that, if it occurred now, would upend human civilization. If you’re not sure how Antarctic ice sheets can impact global sea levels, you should know that there’s enough ice on the southern continent, if melted, to raise sea levels nearly 200 feet. That’s why I described the mass of East Antarctic ice as “inconceivably large.”

This was back in 1997-1999. I visited the project briefly by helicopter in 1998, I think, when I was working several miles down the coast at a three-person helicopter refueling station called Marble Point. Marble was, and is, a waystation for helicopters shuttling science personnel and equipment between the main base (McMurdo Station, 60 miles away) and science camps in and around the mountains.

Cape Roberts was one of those camps, but unique in some interesting ways. The one that got my attention was the method used to support the weight of a huge drill rig on sea ice: two massive flotation bags that provided nine tons of buoyancy for the seventeen ton rig. Summer sea ice in Antarctica is thick and strong enough to land planes on, but not for long. The ocean warms and melts it from below until it breaks up and becomes open water. The entire Cape Roberts drilling operation was designed for that ephemeral reality, not only by using the float bags to boost ice stability but also by making the whole set-up portable: drill rig, operations buildings, and everything else had to be towed onto land before the ice broke out.

After the third and final season, the whole camp traveled back to New Zealand’s Scott Base, which is next door to McMurdo. It was a slow caravan, though, and the team spent their first night at Marble Point. The science groups had gone home, so our guests were a skeleton crew of New Zealand operations staff. Kiwis being Kiwis, and with a final successful season behind them, it was time for a party.

So we got out the grill and the beer and whiskey, and we set up the worst horseshoe pits on Earth. If you haven’t played horseshoes – and the Kiwis certainly hadn’t – the posts should be forty feet apart and the pits should be filled with a mix of sand and clay. This was an impromptu party, so we stuck two stakes in the gravel of the coastal moraine and spent the evening watching iron horseshoes bounce like ping pong balls off the stones.

The stakes grew as the party went on into the odd hours of a sunlit night. (Darkness never falls in the polar summer.) Before long, we were wagering the entire Marble Point camp and they had anteed up the Cape Roberts caravan. It should have been an easy night for the U.S. – and for a while it was – because the Kiwis were throwing overhand and sidearm. You’d think a rural nation proud of its farms and livestock would have a history of horseshoe-playing, but they didn’t have the slightest idea. We instructed them, but they insisted on experimenting. Antarctica is a continent set aside for science, after all.

The problem was the stony ground. The camp manager or I would throw a lovely flat and gently-rotating shoe right at the post, but instead of sliding into place it would clang off in random directions, often threatening to take out someone’s ankle. The Kiwis’ bizarre overhand tosses were just as productive, and after a while they took the lead. We were down to just our outhouse. Only the reality of a rational universe saved us, as our underhand throws brought us finally to a slim victory. In the interest of geopolitical stability, we granted them their equipment back and then everyone found a place to hide for a short sleep while the sun spun overhead.

All of which is to say the photo has a history. It sits on my Welcome page not for that history, though, but because for me it captures a lot of how I see the Anthropocene. There is at first glance the incongruity of dirty fuel barrels in the pristine icescape, the dark against the light and the question it raises about the ethical trade-offs of creating scientific outposts in the last clean place on Earth. All outposts are microcosms of their home culture, and in these Antarctic camps you see symbols of both the genius of science and its trail of destruction. This tension has largely defined the last few centuries. Our rapid domination of life on Earth is rooted in the application of scientific knowledge to harmful behaviors, and has cast a shadow that grows longer by the day. We risk a manmade darkness falling permanently on hundreds of thousands of species in this century. The shadow exists even in the places where science is specifically devoted to understanding the harm and finding solutions to it.

There is also in the photo a blunt symbol for our supervolcanic burning of millions of years of fossil fuels in mere decades. The resulting greenhouse gas production is already transforming the edges of the Antarctic ice sheet. The ice you see in the background stands in for the impact we’re having and for the impact Antarctic melting will in turn have on us. I love the “Caution” sign that summarizes all of that, and the irony of the “No Smoking” warning in the context of climate change.

And finally, I suppose, there is a personal note. The photo is a reminder of my long experience in, and love for, Antarctica. It is also a reminder of my complicity in our contamination of it. I spent four summers on the ice working with fuel, and another few working with the planes that burned millions of gallons in their flights around the continent. I was happily working at the far end of the civilizational claw, loving my time in the outpost’s outposts at the end of the Earth.

I had a front-row seat to the reality that the reach of the Anthropocene is absolute – there is no place or habitat on Earth we have not now diminished or threatened – but it was also, every day, a reminder that the natural world is astonishing beyond measure. I spent my days at Marble Point fueling the occasional helicopter that came swooping in over the glacier, and often spent my evenings walking across the moraine or sea ice exploring a place few humans have seen or will ever see.

I’ve lived with a troubled joy ever since. When you’ve seen deeply into that kind of wild beauty – the nature of nature – the rest of our ruptured world seems pretty strange. And so I write about it, to make sense of it as best I can.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

From the BBC, a reality check on the downsides of the climate-fighting portions of the Inflation Reduction Act pushed through the Senate. The massive long-term giveaways to the fossil fuel industry perpetuate the problem even as we grope for solutions, and in many cases (new pipelines, new drilling, frontline communities in the battle against climate-intensified storms, etc.) the people who can least afford a continuation of the norm will suffer because Congress failed to care for them as much as they cared for technical solutions like heat pumps and electric vehicles. This is not to say the IRA isn’t remarkable for what it achieves, but that the compromises that made it possible, and the people it impacts, should not be forgotten.

From Bloomberg Law, an article by Maya Van Rossum, leader of the Green Amendment movement which seeks to embed the right to a healthy environment in state constitutions across the country: “Without constitutional framing, grounding, and oversight,” Van Rossum says, “environmental protection and justice are easily undermined by the vagaries of a political system where the desire for political power, misplaced ideologies, and/or simple greed routinely overwhelm the greater public good.”

From National Geographic, a story of dust in the wind. Or really, it’s a story of how dust in the snowpack of the Rocky Mountains is causing earlier melting and reducing available water in spring and summer for rivers throughout the western U.S.. The dust is arriving from around the region, even Mexico, and is in large part due to climate-change-enhanced drought and to our disturbance of fragile desert soils. My old Antarctic friend Jeff Derry, now Executive Director of the Center for Snow and Avalanche Studies, is at the center of the piece. (As a bonus… you can read about their findings on microplastics in alpine snow here.)

From The New Republic, an excellent personal essay on why our individual actions in a planetary crisis are both insignificant and very important. Sure, installing a heat pump in your house to replace your oil furnace won’t save the world, but each of us is “a node for social, political, and moral contagion,” as Ezra Klein has written. If we tell our neighbors (online and in the real world) how much money we’re saving on fuel, the tiny action becomes bigger. Individual action isn’t as important as good policy that shifts cultural behavior, but what we do can influence the people around us, who then go on to influence others. That’s also how we shift culture.

From the Guardian, a comprehensive analysis of how many of the world’s intensified droughts, wildfires, heat waves, storms can be attributed to climate change. How much? Far too much, especially given that we’ve only warmed by about one degree Celsius: “Seventy-one per cent of the 500 extreme weather events and trends in the database were found to have been made more likely or more severe by human-caused climate change, including 93% of heatwaves, 68% of droughts and 56% of floods or heavy rain.” And this is merely a “feverish Earth,” as Bill McKibben calls it: “The fact that we’re currently headed for 3C of temperature rise, in the light of these studies, is of course terrifying. And 3C won’t be three times as worse – the damage will be exponential, not linear.”

From Grist, an article on the rapid decline in the natural sounds of life on Earth. The species and habitats we’re diminishing are quieter, and that’s a problem for them and for us: “Without these ambiences to lure us outside, to calm us and restore our flagging spirits,” a soundscape ecologist told Grist, “human culture becomes dystopic and pathological.”

How bad is the global PFAS crisis? If you judge it by nearly any metric – toxicity, linkage to cancer, how widespread it is, the level of industry malfeasance, failure of government to safely regulate it, and the likelihood of it becoming far worse before it gets better – it is terrible. The most recent evidence is a study showing that PFAS levels in rain and snow around the globe, even in Antarctica, exceed European safety limits for drinkable water.

I just subscribed and this is my first read. It is moving and fascinating. I look forward to reading more. Thank you for your writing

Thanks for the Ice story Jason. Lots of Marble Point memories and adventures out there.