Inhabitants

1/29/26 - Listening to those who restore the world

Hello everyone:

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read some curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

What does it mean to live in a place? To truly inhabit it? Is there a threshold of experience or depth of relationship necessary to be an inhabitant? Or, as we now commonly believe, is it true that once we drop our bags, pay the bills, and lock the door we’re home? More broadly, in an era of accelerating ecological destruction, when even the most Earth-conscious among us participates in systems that erase the real world in order to build an abstract and largely meaningless one, are any of us home?

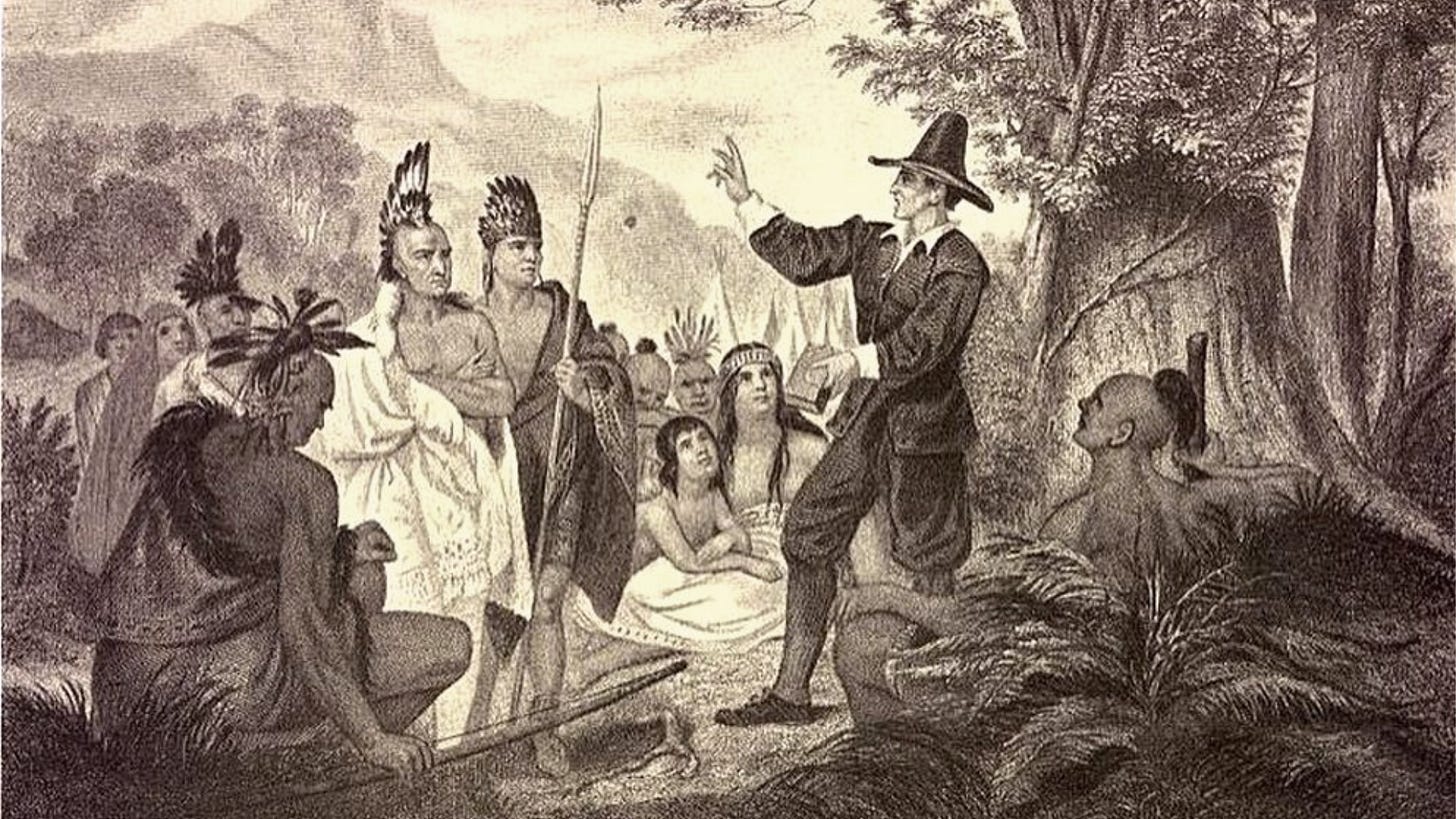

I think it was while reading Francis Jennings’ magisterial book, The Invasion of America: Indians, Colonialism, and the Cant of Conquest, that I first understood how in pre-invasion America a person could not simply move from place to place - Maine to California, say - because each of those lands (and every one in between) contained territories that defined, and were defined by, its inhabitants. (Such limitations seem impossible now, as we live under the online delusion that all things are doable and knowable.) As elsewhere across the world and throughout pre-colonial history, to be human generally meant being as rooted as plants in the landscapes that fed us.

Despite Jennings’ thorough documentation, other people and other times are largely a mystery, of course. Perhaps a Nanrantsouak or Abenaki from the Dawnland Confederacy here in midcoast Maine could have wandered westward along trade routes and, by the grace of his hosts along the way, finally arrived in, say, Yurok lands, where the sun set over a different ocean. Who knows? So many such intimate histories were erased long ago.

I read The Invasion of America in college, in the mid-80s, and there are several reasons why that book became vital to me. It was a very dense book I read for no assignment but my own curiosity. I was so enthralled by the power of the prose and the shock of the history being revealed that my underlining and highlighting thickened into uselessness. I learned the true meaning of “decimation,” which is to reduce a population by 90%. And, as a result, I began to understand the depth of colonial violence and cultural disrespect that persist in the foundation of our politics.

Here’s Jennings on the first page of his Preface, redefining the “colonial” period from a Native American perspective - as an era of invasion - and making clear his intent to clean up the historiographical mess:

The Indian attitude seemed normal enough to contemporary Europeans, who armed themselves in anticipation. The invaders also anticipated, correctly, that other Europeans would question the morality of their enterprise. They therefore made preparations of two sorts: guns and munitions to overpower Indian resistance and quantities of propaganda to overpower their own countrymen’s scruples. The propaganda gradually took standard form as an ideology with conventional assumptions and semantics. We live with it still.

As I understand it, Jennings was one of the first historians to look honestly at colonial/invasion history. It took many years for society to (mostly) catch up. (The current administration is a throwback, looking to erase the honesty.) Here’s a bit of a review of Jennings’ outsized impact on how historians viewed the era:

With cutting, sarcastic, sometimes vitriolic language, Jennings hacked away at the foundational myths of this country's colonial past, providing meticulously researched blow-by-blow accounts of European machinations to defraud Indians of their land, together with colonists' justification of that theft with their oft-repeated claims of Indian "savagery" and European “civility.”

We, the descendants of those colonists and the inheritors of their project, continue to reshape and anonymize the Earth for our unsustainable purposes. We do so with far too little regard for the societies who managed to thrive for millennia without upending life on this planet. Savagery and civility are still used as synonyms by the worst of us who hold power.

Again, I ask, what does it mean to live in a place? Is an invader home? Are his descendants home, even if they still don’t know or respect the land and waters? Perhaps the question isn’t What does it mean to live in a place? but What does it mean to live?

It is essential for the survival of life as we know it that we weave the story of our untethered culture back into the real world. We can no longer pretend that culture, economics, and ideology are somehow more real than ecology. How we think must align with how nature works.

As I think many of you acknowledge, some of the answers we need lie waiting for us in the stories and actions of Indigenous societies. Though they often remain marginalized by the colonial dialogues of economics and private ownership that underpin our lives, these peoples still live with us and alongside us, adapting to the world we’re making from the world we’ve disrupted. Those of us who tell stories need to help with the weaving.

That said, I’ve been leery about writing about Indigenous practices or worldviews. I still am. I don’t have the roots or research to speak with depth or honesty for others’ lifeways or others’ ideas on how to live. But I can connect you to Indigenous stories that pierce the fog of the Anthropocene, which is why I want to introduce you to a quiet, effective 2022 documentary that I just stumbled upon: INHABITANTS: Indigenous Perspectives On Restoring Our World. That site has the trailer, and you can pay to watch the film on Vimeo, among other places. I highly recommend it.

I don’t want to diminish the film’s impact by detailing too much of it here, but it weaves together five stories of Indigenous land management:

A “250th generation” Hopi farmer (and PhD in Natural Resources), Michael Kotutwa Johnson, providing context and wisdom for the seeming miracle of growing corn and beans in northern Arizona without irrigation.

A community of Karuk land managers using fire in northern California to rebuild their people’s ancient relationship with the land. Fire, applied as it was for millennia before colonists arrived, improves wildlife habitat, increases forest food production, encourages the growth of better basketmaking materials, and protects the community from the flames of more intense fires kindled by the mistakes of U.S. forest management over the last century.

Blackfeet leaders in Montana working on a multigenerational project to bring back iinii (bison) - with all of their ecological and spiritual benefits - to their lands. Their bison restoration work is part of a much larger effort by 69 tribes in 19 states to restore buffalo to buffalo country, and rebuild cultures that have long relied upon them.

Menominee forest managers in Minnesota actively and responsibly logging their land according to deep-rooted principles - ecological and communal - in relationship with the forest, as they have for many generations. What they harvest depends on what the forest offers, not what the market demands.

Community leaders on the big island in Hawaii working to reconnect people to their once-abundant food forests. The island’s forests, much of them now long cut down and replaced by monocropped fields, were once carefully-tended agricultural marvels, producing year-round bounties.

I was really struck by the theme of pragmatism that connects all the stories. The tone from tribal members and leaders alike sounds like This is how we do things to survive on this part of the Earth, rather than front-loading their actions as spiritual activity. When I wrote above that the answers we need lie waiting for us in Indigenous stories and actions, this kind of pragmatism is what I meant. Not merely the words of “living in relationship with the Earth” but instructions for staying alive.

What I think I understand, after watching this, is that spirituality does not guide fire-based land management, say, or the management of forests for Menominee timber or Hawaiian food. It’s not We believe this so therefore we’ll do that. Instead, it’s This is what has worked for thousands of years, so therefore it is sacred to us. The spirituality emanates out of relationship with reality, rather than being a set of ideas whose consequences are inflicted upon the land. As Leaf Hillman, a Karuk ceremonial leader, explains:

Our religion is survival in this place, living in this place for countless generations, thousands of years. It’s hard to say it’s a religion. It’s really management practices that have evolved in this place to survive. And fire, in our creation stories, there’s a recognition that fire has always been here. It’s always been a part of us.

Such pragmatism generates deep joy. Blackfeet children who had been exposed to bison/buffalo for the first time were asked by the Iinii Initiative, “What do iinii make you feel?” One wrote, “They feel like myself.”

Such pragmatism also generates honesty about the past and the future, as best we understand either. As Kalani Souza of the Olohana Foundation reminds us,

The American industrial complex spent 130 years ruining the capacity of the Native Americans, all in an attempt to commit genocide against a group of people. So it’s time for the United States to own up to what it’s been responsible for, and to honor the ways of the people who were on the land before you and incorporate those ways into our everyday living.

And Leaf Hillman, looking at the crises unfolding around us, took it a step further:

People today are all excited about climate change, and rightfully so. People are rising up and panicking, in a sense. They recognize that this is not sustainable. That’s a good thing that it’s happening, that reaction.

But it’s going to be imperative - it is imperative - that these people and these movements that are beginning to grow look for and accept guidance from Indigenous people who know how to adapt and respond to a changing environment. We’re still doing it today, and we’ll continue to do it until, as we say, the stars fall.

The good news is that there’s evidence all around us of the good influence of Indigenous thinking, and of actions by activists and scientists and governments that bring us slightly more in alignment with the reality that Indigenous cultures understand better than ours. The U.N. COP30 climate conference in Belem, Brazil, had a far greater level of Indigenous peoples’ participation. The patient and ethical long-term reporting on Indigenous land issues from sites like Mongabay pays off in keeping these stories present in the media “ecosystem.” State and federal authorities in the U.S. have in recent years entered into co-management agreements with tribes for parks and other protected lands. Tribes are partnering with conservation groups to step up where the Trump administration is siphoning funds away. Scientists are more likely to work with tribes for assessment and data-gathering.

All of these tradition-linked efforts are wonderful, but are occurring at far too small a scale. This is due in part to the irony that while we think too little of Indigenous peoples, we are at the same time asking too much of them. There is the oft-reported statistic about Indigenous peoples making up only 6% of the world’s population while managing 25% of the world’s land surface and supporting 80% of global biodiversity, but as the brilliant Tyson Yunkaporta explained in an introduction to his book, Right Story, Wrong Story: How to Have Fearless Conversations in Hell, how the hell are they supposed to do all of that?

We all try really hard, but I tell you, I’m sick of hearing this rubbish statistic about eighty per cent of the world’s remaining biodiversity being diligently cared for by Indigenous Peoples. Most of us have only nominal Native Title and no real control, “co-managing” the land at best, in ways that facilitate mining or agricultural interests, while we struggle to feed and shelter ourselves in the economy of the occupying culture. That doesn’t leave us much time to look after the shred of biodiversity left in their water reserves, agriculture complexes, real-estate developments and mining leases. Our family does continue this work in our sacred places (the ones that haven’t yet been blown up or bulldozed), but it is very hard to cram it all into a weekend.

Which means, of course, that it’s not up to them. It’s up to us to support them, and more importantly to act a little more like them. How? By becoming better inhabitants.

In Kerry Hardy’s introduction to his book, Notes on a Lost Flute: A Field Guide to the Wabanaki (a truly wonderful book for anyone living in Maine or nearby), he suggests that if his book is appropriately respectful and true about the people he’s writing about, that it will help guide us closer to a meaningful life upon the land:

I hope that these resurrected glimpses of an original American landscape and its people do justice to both… Notice the order in that last phrase - the landscape owned the people, not the other way around. We Euro-Americans have worked hard for four centuries to invert this relationship, to our collective shame and loss, as more species and ecosystems slide toward oblivion… Perhaps in these essays some will find reasons to believe, as I do, that Indian landways and lifeways still offer viable models for an American future that’s yet to be determined.

For all of you living elsewhere (particularly in the Americas and Australia/NZ), if you want to know where you live, as defined by the last several thousand years (minus the last few centuries), visit the Native Land Digital site and type in your hometown. What appears is a nuanced map of pre-colonial relationships to place and the peoples defined by that place. Meanwhile, the Native Land “About” page reminds us that

Land and waters are sacred. They hold memory, meaning, and life. Whether we’re aware of it or not, the land gives us everything — it is where we live, breathe, grow, love, and connect.

That’s a map of home we can all live on.

I want to note that while I haven’t written much here about Michael Kotutwa Johnson, he’s important to the film and an eloquent spokesperson for restoring the world. I went looking, and found another short, excellent interview with him talking about his relationship with the land. It’s by the folks at the wonderful Leave It Better Media here on Substack, which aims to “tell stories about people who are actively working to heal the Earth and the people in it.” This is largely through farming and food systems, as far as I can tell, told through a fine and restless form of documentary filmmaking. Spend some time with their work, and support them if you can.

Finally, I should admit that I haven’t really tried to answer all of my rhetorical questions about what it means to live in a place. I’ll admit also that adopting sustainable relationships with fire and forests and desert rain may not answer that question very thoroughly in a world of 8.3 billion people wedged together between concrete and the endless needs of capitalism.

But it helps at least in turning the attention of inhabitants to the land and waters they inhabit. If everyone tended to where they lived, I think, then everyone would be home. Broader solutions can emerge from local ones, and perhaps an ethics or spirituality will emerge later. Who knows? Such intimate stories lie in a future we will all have to work to create.

Meanwhile, healthy Indigenous societies will keep doing their thing, at whatever scale they can, living lives that are better for all life, even amid the harms of the dominant culture.

As a Karuk fire crew leader put it: “We’re fix-the-world people. We have ceremonies for that.”

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

From Michelle Nijhuis and Conservation Works, “The Other Crisis in Minnesota,” a nuanced but vital discussion of how Republicans in Congress are angling to use the Congressional Review Act to repeal Biden-era rules banning mining and geothermal leasing in the magnificent and protected Boundary Waters region. More broadly, what these conservatives are after is to normalize the ability of Congress “to undermine the whole practice of conservation on U.S. public lands” and “to give Congress the power to veto almost any rule issued by a federal government agency.” You’ll need to read the entire short piece to understand the issue fully, but this is major threat on the conservation horizon.

From David Roberts and Volts, “How to make rooftop solar as cheap in the US as it is in Australia,” a great wonky and fun podcast conversation with two guys who are devoting their lives to making the cost of American rooftop solar affordable for anyone. In Australia, a system can be ordered, permitted, and installed in days, for a third of the cost paid here in the U.S., where it can take months and months. If you’re looking for ways to help make it happen here, the podcast has plenty of information.

From Rhett Ayers Butler at Nature Briefs, “What Endures,” a review of the impacts of Butler’s decision 15 years ago to start a nonprofit to support Mongabay, the incredibly important global environmental news service he founded:

Legacies are often clearer in retrospect than in real time. For now, Mongabay’s work continues, shaped by the same constraints and uncertainties that define the broader media landscape. If there is a lesson in its history, it is not about scale or prominence, but about patience. Attention, when applied consistently and carefully, can still change how the world sees places it once ignored. That may not be a grand achievement, but it is a useful one.

From Undark, an ecologically philosophical question that is, in the end, a political question: Who Gets to Decide How Much Is ‘Enough’ to Live a Good Life? The more societies, their scientists, and their leaders begin to discuss setting limits on consumption and wealth while working to raise standards of living for those who have too little, the more political the effort becomes. Nearly everyone believes that life should be fair, and that excess wealth should be curtailed, but few of us like to be told what to do. For the sake of reining in our planetary excesses, though, we’ll need to figure it out soon.

From Yale e360, a very somber report on how the death of 1.5C as a civilizational goal to limit climatic heating may mean incredibly difficult consequences around the globe:

In particular, there is a growing fear that climate change in the future won’t, as it has until now, happen gradually. It will happen suddenly, as formerly stable planetary systems transgress tipping points — thresholds beyond which things cannot be put back together again.

From DeSmog, an anonymous group of executives at some of the world’s largest advertising agencies has put out a statement warning that their companies are very much on the wrong side of history:

“We know our industry is funding hate, legitimising environmental destructive companies, and working at the frontline of a US-led rollback on diversity, equity and inclusion” (known as DEI), they said in the memo, while “paying little more than lip service to solving critical issues” that include “spreading hateful content” and “helping polluting industries such as oil and gas rebuff public scrutiny.”

In related but better news from DeSmog, Amsterdam has become the first capital city to ban ads for fossil fuels.

From Inside Climate News, an ever-shrinking number of large companies - down to 32 now - is responsible for over half of global climate-heating emissions. The bulk of the article explains the usual crime-without-punishment facts of the story and its villains (state-owned oil and coal companies, largely) but the ending has a nice kicker, leaving us with two hopeful efforts to help squeeze these corporations out of existence: The Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty Initiative, which I’ll write about someday, and the world’s first International Conference on the Just Transition Away from Fossil Fuels, coming this April.

From Mongabay, a new U.N. report offers a dark truth about a subject that’s too little known or discussed: “water bankruptcy.” Using the language of capitalism - perhaps to catch the attention of GDP-distracted politicians - the report suggests that rain, snow, and rivers are like “income,” while glaciers, wetlands, and aquifers are like “savings.” People across the regions of the Earth have drawn much too heavily on both hydrological income and savings, and are now badly underwater (as it were):

When glaciers melt and aquifers are pumped dry, those resources can’t be replaced in a human timescale. Scientists have long warned of a global water crisis, but water bankruptcy is the post-crisis stage of irreversible damage to water systems. “The language of crisis — suggesting a temporary emergency followed by a return to normal through mitigation efforts — no longer captures what is happening in many parts of the world,” the report authors note.

Very interesting , Jason. I look forward to your reading suggestions to educate myself. And to think, that we are in this timeline where our president, and all of those whispering in his ear, are happily erasing history. Like a Twilight Zone story, written by the great Rod Serling. I imagine he might depict the process with a child using a big eraser, happily erasing away. I haven’t decided if it would be a history book of the United States of America, or a map of the world being erased.

I loved this look at indigenous culture. Starting with the first exploratory movements of groups who considered that they represented an advance culture (which meant advanced weaponry) the use of power was justified by labeling the other groups as inferior, savage, or heathen. Being tone deaf was a worldwide condition - send missionaries, disregard their intelligence, their religion, their knowledge and force them to learn our ways even though they would still be inferior and in the meantime -take what we want!