Milestone and Millstone: 8 Billion

11/17/22 – Is it possible to make a society of 8 billion humans sustainable?

Hello everyone:

If you’re looking for a way to help stop Russia’s genocidal war in Ukraine, read Timothy Snyder’s latest and donate what you can. (He would like your help in purchasing a missile defense system.) Thank you.

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read some curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

The U.N. has declared that human population officially reached 8 billion a few days ago, on November 15th. No one knows actually knows when the human odometer clicked over and began the count toward 9 billion, but the U.N. needed a podium moment to make an announcement and provide some optimistic context. “Eight billion people, it is a momentous milestone for humanity,” said United Nations Population Fund chief Natalia Kanem, who hailed the modern decrease in maternal and child deaths and the increase in our life expectancy. She also said this:

Yet, I realise this moment might not be celebrated by all. Some express concerns that our world is overpopulated. I am here to say clearly that the sheer number of human lives is not a cause for fear.

I am here to say clearly that the number of human lives, as the U.N. well knows, is driving Earth’s rapid ecological decline. 8 billion is as much a burdensome millstone around our neck as an unprecedented milestone. Kanem is right that we should not “fear” the numbers, because popular fear about population has often resulted in racist eugenics programs, forced sterilizations, and authoritarian efforts to control women’s reproductive lives.

But the U.N. Population Fund provides some of the best data on population and is at the forefront of efforts to fund family planning efforts around the globe. As vitally necessary as it is for improving the lives of women, voluntary family planning is also the primary tool used globally to slow population growth. (Again, this is voluntary: women around the world want the power and dignity of controlling their own reproductive capacity.)

In fact, Kanem’s announcement took place on the sidelines of International Conference of Family Planning. Likewise, some discussions at the current U.N. Climate Conference in Cairo and the December U.N. Biodiversity Conference in Montreal will no doubt continue to quietly recognize the role that a burgeoning human population has played in creating those crises. Certainly the IPCC has noted that “globally, GDP per capita and population growth remained the strongest drivers of CO2 emissions from fossil fuel combustion in the last decade.” And the 2022 Living Planet Report cites population growth as an important driver of biodiversity loss.

But where the U.N. was once comfortable talking about overpopulation they now speak of the challenges of “population trends” amid an era of rapid urbanization and climate change. The U.N. learned some time ago that they are more effective discussing and creating solutions than rhetorically raising the Malthusian spectre of an overrun Earth. (It’s hard enough to get funds from the U.S. for family planning without challenging the evangelical tenet that an abundance of babies is an homage to God.)

Reaching a global population of eight billion is a numerical landmark, but our focus must always be on people. In the world we strive to build, 8 billion people means 8 billion opportunities to live dignified and fulfilled lives.

That’s UN Secretary-General António Guterres, who has been notably outspoken in advocating for civilizational shifts to reverse climate change (“a Code Red for humanity”) and biodiversity loss (“our senseless and destructive war against nature”). Here, as expected, he is more circumspect. The “focus on people” is a double-edged phrase, though. Guterres certainly understands that the well-being of humans in the industrial age has come at the expense of the natural world, and that the suffering of other species now threatens human well-being.

My point with this week’s essay to assert that if we want every living human to lead dignified and fulfilling lives surrounded by a healthy natural world, then we will first need to achieve a smaller population.

Why? Because life on Earth is disappearing. One of the defining characteristics of the Anthropocene is how, in the community of life, we now create the conditions that increasingly define who lives and who dies. Our actions determine the fertility and mortality of most other plants and animals. Some of this “control” is through blunt force as we erase habitat for development and extract what we need (or think we need) from what remains. Some is the result of our pollution and toxic contamination of environments that struggle to recover. Some is due to our overheating of the oceans and atmosphere. The rest is a function of our stumbling our way into a planetary-scale management of livestock, crops, orchards, and wild-caught food.

The result, so far, is an increase in the extinction rate that surpasses that of most previous mass extinctions. As far as we know, only the dinosaur-killing Chicxulub asteroid was faster. To be clear, though, we are not yet in a global extinction event, nor are we committed to one. We are on the cusp, with the path forward to be defined by the choices we make today.

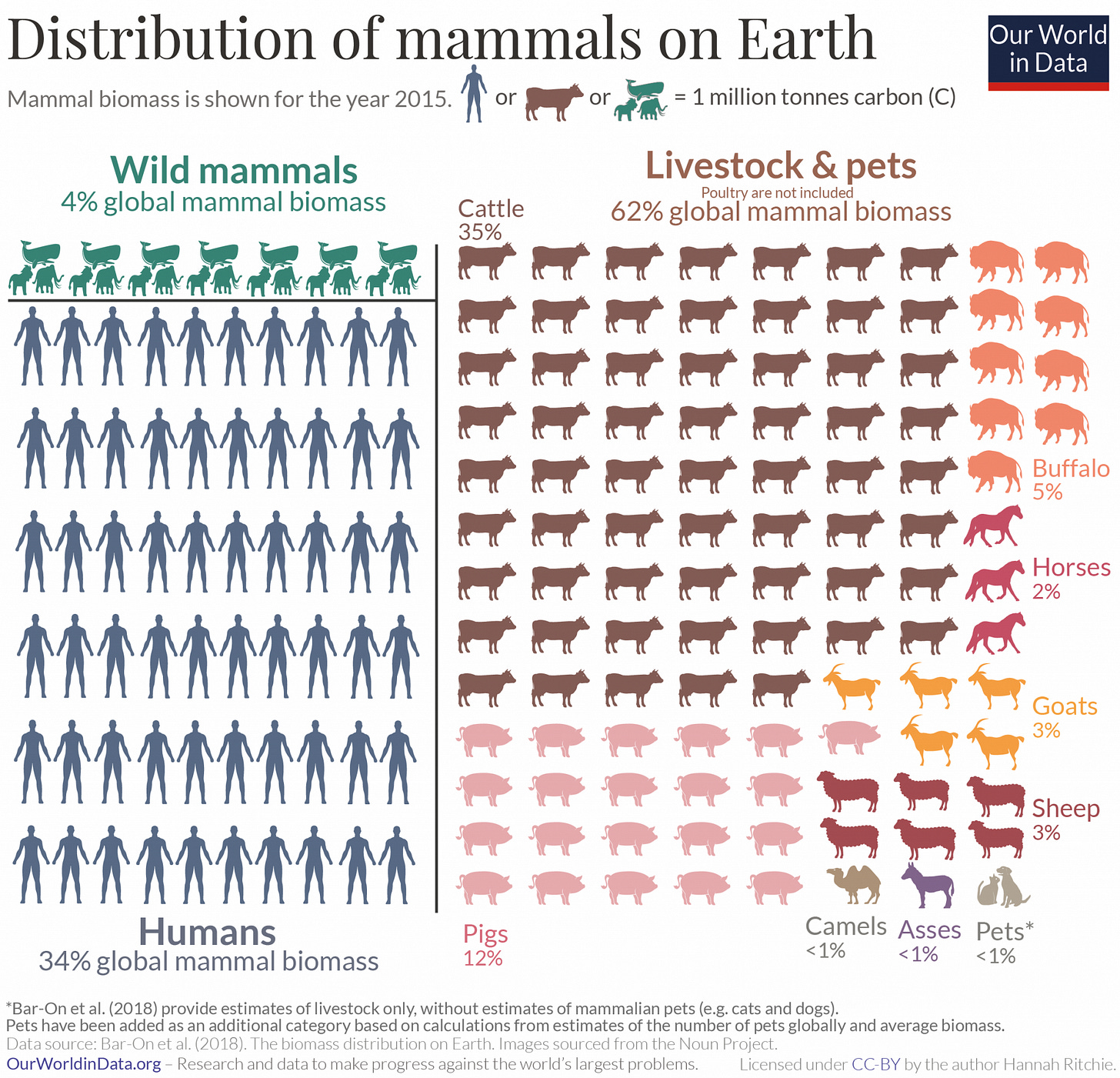

We are still making the wrong choices. Landscapes and wetlands disappear under pavement and plow. Rainforests come down so that cows can move in. Pesticide-soaked corn and soybeans thrive in biological deserts we call farms. Thousands of tons of shark fins arrive in port as the sharks’ habitats unravel. The 2022 Living Planet Index shows a nearly 70% average decline in the thousands of wildlife populations it has monitored over the last 50 years. Wild mammals now make up only 4% of global mammal biomass; the other 96% are us and our livestock. And now a warming climate is disrupting ecosystems even in areas untouched by chainsaw or hoe.

There has been an unspoken assumption that we have the right to these impacts. A growing civilization needs to eat, right? We have jobs to do, kids to raise, and lives to live. We have an economy to support and serve. We’re making progress! Only when we say the words out loud – We decide the fate of nature, regardless of consequence – does the bubble pop and we feel like we’re actually on shaky moral ground.

Our impact on life and death has been, to a large degree, a function of not limiting our own fertility. Or rather, of encouraging our fertility even as we succeeded wildly at reducing maternal and child mortality and increasing life expectancy. Population has quadrupled from 2 to 8 billion in the last hundred years, though it took all of human history to reach 1 billion in 1804. We’ve been adding a billion every 10 to 15 years since 1960, with today’s rate of increase at about 2.4 babies per second, a million every five days.

The good news is that the population growth rate has dropped considerably in the last fifty years – cut in half, in fact, and now just below 1% – but even that tiny percentage of 8 billion adds up to an additional 80 million, the population of Germany, every year.

There are more human babies born each day – about 250,000 – than there are living apes (of all species) left in the wild. This is a statement on both our fertility and its consequences.

But we all know it’s not just the number of people. It’s the amount of resources each of us uses. And for the most part the destruction of the natural world has been driven by a small percentage of people in a few wealthy, powerful nations. Everyone contributes to the losses, but not equally. The wealthiest 10% of the world’s population consumes about 20 times more energy than the bottom 10% and uses 40% of the Earth's biological productivity. The average American, for example, eats 264 lbs. of meat per year, three times the global average.

By all means, a good life should be available to every living human. It’s common decency, smart economics, and good politics. But equitably distributing the destruction of life on Earth does not reduce the destruction. If today’s rate of global consumption – 1.75 Earths’ worth of resources per year, or 75% more than the planet can replenish – were redistributed and shared equally with the billions of people suffering from poverty and hunger, we’d still be using the equivalent of 1.75 Earths.

Our current ecological debt – the gap between what we use and what is sustainable – is depleting the natural world. Without a large-scale effort to protect and restore the environment, the likely consequence will be a cascade of ecological collapses that will in turn make it harder to sustain and enrich human lives. That’s what we’re fighting against in this “global double emergency” of the climate and biodiversity crises.

In other words, the equity our civilization needs isn’t just about people. We are also obligated to give other species their own dignified and fulfilled lives.

I don’t like saying this, but the optimism that we can fully feed, house, and educate 8 billion (or the 10 to 11 billion that are due by 2100) while also restoring and rewilding life on Earth doesn’t feel like optimism. It feels like fantasy, not least because worsening climate change and biodiversity loss in the next half-century are liable to intensify hunger and poverty. We need look no further than the extensive crop damage from unprecedented heat, drought, and floods in China and Pakistan in recent months. Progress will likely also be slowed by the political and economic chaos in hungry, storm-wracked nations, and by the additional Germany of babies each year.

Thanks to the U.N. Sustainable Development Goals and related initiatives, progress is being made, but not nearly enough. Despite the extraordinary wealth, technology, and advances in healthcare created over the last century, more than six hundred million people still live in extreme poverty and nearly two billion live on less than US$3.65 per day. 2 billion is the entire human population alive in 1927, only 95 years ago.

Even if it were politically possible, it may not be logistically possible to reduce consumption in wealthier nations anywhere near enough to 1) level the playing field to benefit the rest of the world while 2) still reducing total consumption. We need relatively harmless sources of food, shelter, and energy on a global scale, none of which exist. (Even clean energy has a dirty future, largely because of increased mining.) As an excellent “myth-busting” page at Population Matters explains,

There must be a convergence in living standards, where the rich take far less and the poor have far more. While we continue to add people and their inevitable demands for resources to the population, however, we are putting pressure on the Earth that it cannot sustain.

An equitable future for all people means creating opportunities that include access to a comfortable, moderate wealth (housing, technology, transportation, health care, and more). But how many middle-class humans can the Earth sustain and still be a vibrant blue-green planet?

Note that this is a very different question than How many people can we fit on the Earth?, which is really asking how much of the planet we can sacrifice to squeeze in more babies. I’ve written about the question of Earth’s carrying capacity before, so I’ll focus instead on explaining why a sustainable human civilization, should we choose to build one, is unlikely to include anywhere near the population we have now.

But not until next week… And I promise that I’ll keep it short and finish with some wonderful, positive news on the biodiversity front. We could all use some good news to be thankful for on the Thanksgiving holiday.

I’m very curious for your input and critique on these questions of population and sustainability. I know that I’m painting with a very broad brush here, so please send comments and questions. I really would love for the Field Guide to become more of a conversation.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

Two excellent sources for biodiversity reporting: Vox’s Down to Earth series and the Guardian’s Age of Extinction section.

From Kontinentalist, an illustrated investigative essay into the rare earth metals that are powering the green tech revolution (your phone, your Tesla, your wind power). This is the dirty side of clean power. The article speaks to the general problem but zooms in on China’s extraction of these metals from Myanmar, which under the military junta has no mining regulations.

From the Guardian, a major study finds that the Earth is already on the verge of several significant and irreversible climate tipping points. These include the collapse of the West Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets, melting of Arctic permafrost, and large-scale die-offs of coral reefs. A tipping point is defined in the article as “when a temperature threshold is passed, leading to unstoppable change in a climate system, even if global heating ends.” We seem locked in for at least 2°C to 3°C on our current warming path, which may trigger another dozen or so catastrophic tipping points. I’ll write more on this sometime soon.

From Hakai, a fascinating story of whether Greenlanders will decide to allow the mining of sand that’s washing out in vast quantities from their rapidly melting ice sheet.

From Vox, the infuriating story of how corporate America convinced us to spend so much money on bottled water.

From Wired, a great article on two conundrums in taxonomy: How do we efficiently begin to actually recognize and identify the millions of still-unknown species? And how do we do it now that they have begun to disappear? There’s a race against extinctions and a fierce debate over methods. But something has to be done now. As one entomologist put it, “What do you know about the world if you’re only looking at a few species? You don’t know anything about it.”

Explore the powerful new satellite-based Climate Trace mapping tool to see exactly where large volumes of greenhouse gas emissions are coming from around the world. This is a game-changer for identifying specific sources rather than vaguely apportioning total emissions country by country.

"One of the defining characteristics of the Anthropocene is how, in the community of life, we now create the conditions that increasingly define who lives and who dies." This sentence is mind jarring in its moral implications. Who lives (for now)? White people in the North, Black and Brown people in the South? As you note, it was only a few hundred years ago that we created the conditions that are destroying the teeming, beautiful ecosystems that gave us the Anthropocene in the first place. What do we have to blame? The technology: steam engines and factories and cars? The enlightenment? Christianity's blessings on colonialism and saving pagans (otherwise known as stealing their land)?

I was amazed at the optimism of the news media on the topic of reaching 8 billion this week. And horrified that people still seem to believe that growth--any kind of growth!-- is good. Your writing helps with those talking points, but it is still depressing to think about how far people are from understanding these realities, much less acting on them. Thank you, once again, for being a voice in the wilderness.