Restraint and Management

8/22/24 - Barry Lopez, my father, and the transformed Earth

Hello everyone:

This week I’m bringing you a piece that’s special to me, an updated version of the Field Guide’s inaugural essay, first published on Earth Day, 2021. The essay has been edited, rewritten, given a new title, and split into two pieces for this week and next.

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read some new curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

“If I have a subject, it is justice. And the rediscovery of the manifold ways in which our lives can be shaped by the recovery of a sense of reverence for life.” - Barry Lopez

I’m here this week to memorialize a writer and a scientist, and to pass on a little of what I learned from both about our transformed world. I’ll start with the writer.

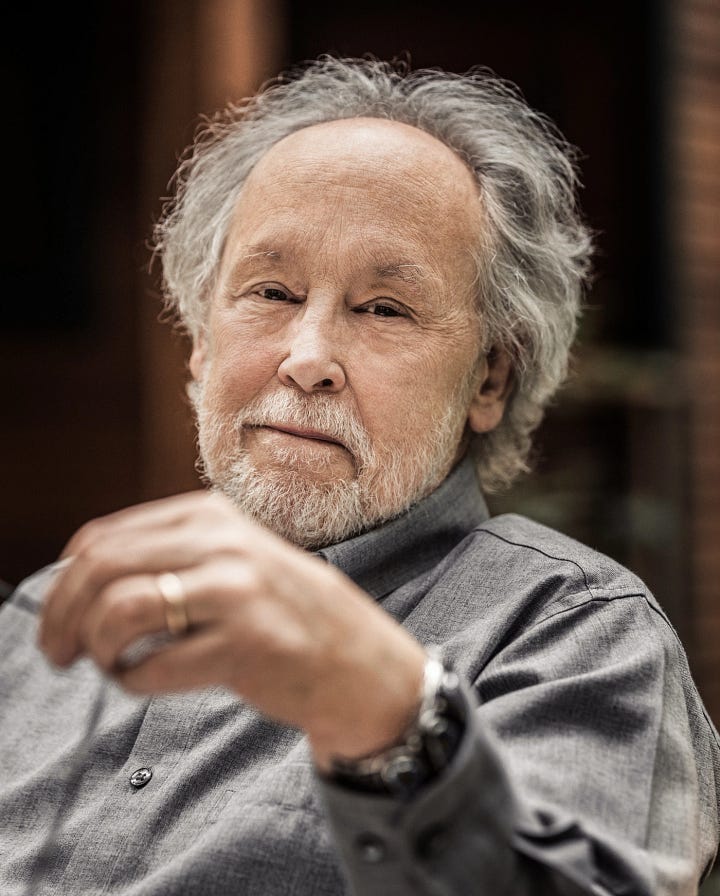

The great Barry Lopez was an extraordinary writer and, by all accounts, an even more extraordinary human being. He died on Christmas day, 2020, leaving an unsurpassed legacy as a writer at the intersection of natural history, scientific inquiry, environmental justice, and indigenous values. Lopez devoted himself to traveling the natural world, and to studying ways of living that predate our pop-up civilization. He did so with a deep respect for both scientific and traditional ways of understanding.

His teachers were researchers, traditional elders and storytellers, wolves, ravens, landscapes, and more. He modeled the values he learned from them in his prose and his actions, and without preaching made it clear how critical those values were for all of us if we want to sustain life on an increasingly impoverished Earth. His gifts as a person were also his gifts to us: A sense of wonder, a deep understanding, and a lifelong, disciplined desire to articulate both his wonder and understanding.

Lopez was a writer of grace and precision. Every page of his books exhibited his grace, but I think often of his less-known short essay, “Apologia,” which I taught many times to students bewildered by his detailed description of the litany of roadkill he encountered on a drive from Oregon to Indiana. Lopez interrupted that journey frequently, pulling over to move off the road the remains of those lives ended by our thoughtless passages. He chronicled his struggle, carcass after carcass, to address each animal with sufficient respect, in intense language meant to make up for our failure to ritualize or even acknowledge the carnage.

Of a young sage sparrow he hit in Idaho, he writes:

I hold the walloped bird in my left hand, my right thumb pressed to its chest. I feel for the wail of the heart. Its eyes glisten like rain on crystal. Nothing but warmth. I shut the tiny eyelids and lay it beside a clump of bunchgrass… The road curves away to the south. I nod before I go, a ridiculous gesture, out of simple grief.

This was his apologia, a formal accounting of one’s actions.

And it was Lopez who first taught me, in his astonishing book Arctic Dreams, that nonfiction writing can sing, even while carrying a heavy load. That is, it can be lyrical while also conveying a depth of information, whether biological or philosophical. No nonfiction writer I’ve encountered since manages to do both so well (with the possible exception of Robert MacFarlane, who has often noted his debt to Lopez). With elegant literary craft, a deeply felt response to place, and a heartfelt devotion to the truth and intent of science, Lopez composed his informed travelogues on a lattice of poetry.

And, he seemed to say, there’s no greater foundation for writing. Density, (en)lightened with grace, can sing. It’s worth quoting him at length – here on the passage of time in the Arctic – to hear his gift:

Time here, like light, is a passing animal. Time hovers above the tundra like the rough-legged hawk, or collapses altogether like a bird keeled over with a heart attack, leaving the stillness we call death. In the thin film of moisture that coats a bit of moss on a tundra stone, you can find, with a strong magnifying glass, a world of movement buried within the larger suspended world: ageless pinpoints of life called water bears migrate over the wet plains and canyons of jade-green vegetation. But even here time is on the verge of collapse. The moisture freezes in winter. Or a summer wind may carry the water bear off and drop it among bare stones. Deprived of moisture, it shrivels slowly into a desiccated granule. It can endure like this for thirty of forty years. It waits for its time to come again.

Long, unpunctuated hours pass for all creatures in the Arctic. No wild frenzy of feeding distinguishes the short summer. But for the sudden movements of charging wolves and bolting caribou, the gambols of muskox calves, the scamper of an arctic fox, the swoop of a jaeger, the Arctic is a long, unbroken bow of time. Twilight lingers. There are no summer thunderstorms with bolts of lightning. The ice floes, the caribou, the muskoxen, all drift. To lie on your back somewhere on the light-drowned tundra of an Ellesmere Island valley is to feel that the ice ages might have ended but a few days ago.

You can sit for a long time with the history of man like a stone in your hand. The stillness, the pure light, encourage it.

Reading Lopez is an investment in patience and thoughtfulness that pays off richly as our own thoughtfulness expands. Witness my grandmother, Sally, in her late seventies, lying on a comfortable couch in the house where she was born, looking out at a small working harbor on the Maine coast. It was on that couch that she read all 464 pages of Arctic Dreams, about four pages per day. “I just like to read that much and think about it,” she told me.

Sally’s life spanned the 20th century, from horse-and-buggies to space shuttles, and I’ve often wondered what it felt like for her to witness the constant disruption of a radically transforming world. Population tripled and entire landscapes disappeared. The ocean floor beyond her harbor had been repeatedly scraped to the bone by increasingly efficient fishing fleets. Hers was perhaps the last generation to wonder if maybe the world wasn’t meant to change so quickly. Ever since, the rest of us have normalized waking to a planet where everything speeds to an uncertain future, and where we now struggle to somehow enact solutions on the same scale.

The story of Sally on her couch reading Arctic Dreams is one anecdote I know for sure I would have liked to tell Barry, had we ever met. And I’d like to think that he and I could have harmonized a bit in talking about Antarctica. We both loved the place, despite (or probably because of) its spectacular indifference to our presence. There’s something like unrequited love that happens when you return year after year to hear your footsteps crunch across the silence of an ice cap two miles deep and six times larger than the Mediterranean.

I had a chance to meet him during one of my first seasons in Antarctica, in the mid-1990s, when I saw him at a table in the McMurdo dining hall sharing a meal with a science group he had joined for the season. I was a young guy just out of grad school with a MA in poetry, writing strange small lyric poems and still adapting to life on what felt like the Moon. Lopez was an experienced Antarctic hand, and had written about it with real power and grace. I didn’t know what to say for myself, much less what I could say that was worth interrupting his meal. So I didn’t.

I had another opportunity when he was scheduled to join a gathering of the Antarctican Society here in Maine in the summer of 2018. He canceled, we were told, because of his health. It’s a long trip from Oregon for an ill man, even one who had doggedly traversed the remote regions of the planet and cheerfully camped in East Antarctica.

Lopez’s final book, Horizon, a masterpiece, was released in 2019 but had evolved on Lopez’s desk over many years as a lens through which he assessed his life, his work, and the path toward a more rational civilization. Horizon speaks of his years of relentless travel to see and understand and describe the distorted world we have each inherited. (There are many excellent reviews of the book, but I recommend one from the Guardian by Robert MacFarlane - linked above - and one by

here on Substack in, coincidentally enough, her newsletter’s inaugural post.) Lopez is peerless in his ability to gently, yet firmly, articulate the world as it is and as it should be:If the real human environment in developed countries today is third-growth monocultured “forests,” tar-sand petroleum, cow-burnt grasslands, and smog-like clouds of microplastics floating in oceans where fish once thrived, then human cultures need to distinguish between sentimentality about loss and the imperative to survive. They need to establish a more relevant politics than the competitive politics of nation-states. And to found economies built not on profit but on conservation.

and

Our question is no longer how to exploit the natural world for human comfort and gain, but how we can cooperate with one another to ensure we will someday have a fitting, not a dominating, place in it.

Horizon feels to me like his own field guide to the Anthropocene, this new epoch in Earth history marked by the ways in which human society has initiated permanent changes to the geologic record. Earth’s wonders and beauty and mysteries, alongside much hard-earned human wisdom, are in the pages of Horizon. And so is the ongoing, increasingly desperate loss of that wonder, light, and wisdom, though always framed by Lopez’s insistence that a better path is available to us.

If the Anthropocene is the result of the human impulse to reimagine the Earth for our purposes, then the only rational path forward will come from doing the hard work of reimagining civilization instead. Lopez’s legacy is to point us in that direction. I’ll say more about this toward the end of this two-part essay.

For anyone new to Barry Lopez, a fine introduction is the memorial page Orion magazine has set up on their site. It offers a couple dozen beautiful notes by poets, writers, composers, etc., all with stories and insights to take you much farther down the beautiful path laid out for us by Barry. Another good source is the foundation he left behind to continue his good work. From these sources, you can trace the path backward to his books, essays, novels, and talks. Enjoy.

My father, Vaughn Anthony, died on Christmas day, 2018, exactly two years before Barry.

Dad had a brilliant career in the National Marine Fisheries Service as one of the top guys crunching data to determine how many fish were in the sea and determining how many should be caught, specifically in the Gulf of Maine and the North Atlantic. This stock assessment analysis always seemed like magic to me. How do you move mathematically from scant raw catch data to oceanic population assessments to smart, long-term multinational policy? And yet he and his U.S. and international colleagues did that, every year, the result of thousands of hours of hard math and harder politics in smoky meeting rooms. I never really understood it, to be honest.

But something Dad emphasized when I was a kid that sticks with me now as I think about the Anthropocene – and this was well before the term had been coined – was that we need to manage the species we impact. In an era in which new technologies had made fishing ruthlessly efficient, we can’t take “resources” without thinking carefully about the taking. Even in my childhood there were far too many of us to properly feed while still respecting the integrity of the natural world (and population has more than doubled since then).

It was my first lesson in what science does behind the scenes while the theater of civilization lurches across the stage.

Dad was only talking about those species we harvest, but before long it became clear to me that the story was bigger than that. Now that we know that every living community on Earth is impacted by human activity through transformations of land, sea, and atmosphere, everything has to be managed. Anything less is privileging our right to decimate the array of life on Earth and undermine our own survival in the process. Under the Anthropocene aegis of “you broke it, you bought it,” the planet’s worth of species we impact are being “managed,” whether we’re paying attention or not. So we can either do the science and make policy to manage all of it as best we can, as Dad said, or we can pretend otherwise and suffer the consequences.

And I’ll talk more about that, while bringing Barry Lopez back into the story, next week.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In curated Anthropocene news:

Here’s one for Dad: From the Times, a new study finds that stock assessments of fisheries around the globe over the last forty years have been too optimistic. This matters because so many fisheries are already overfished or endangered by a host of other threats: acidification, deoxygenation, etc. If the good management being done is actually overcounting fish stocks, that’s another problem in an ocean of problems. As my father knew, stock assessments are fiendishly complicated. The article cites a truism about the work: “counting fish is a lot like counting trees, except that they move and you can’t see them.”

From the New Yorker, a brilliant exploration of the concept of sea level, which in this era of rapid warming we think of as an objective measure but is really “a social and historical construct, the result of an inherently arbitrary decision taken by generations of people doing their best to make sense of a strange and chaotic world.”

From the Atlantic, the “hot-steel problem” in the U.S., as rising temperatures make a hot mess of train tracks, roads, power lines, batteries, and more. There is much to do to prepare, from policy to engineering, but “You can’t reengineer all of U.S. infrastructure as quickly as the climate is changing,” as one expert put it.

From

at Street Smart Naturalist, a fun piece on a bit of good glacial news: The world’s youngest glacier is doing okay in the crater of the volcanic Mount St. Helens in Washington.From the Guardian, the link between anthropogenic methane emissions and impacts on the Amazon and other vital wetland ecosystems, and some clear-eyed advice about the difference we can make to reduce them.

From Anthropocene, nearly a quarter of Europe has the potential to be rewilded into wildlife havens, according to researchers, but not nearly enough of those regions have been protected.

Also from Anthropocene, the devastation of vulture populations in India (poisoned by widespread use of a generic pain-killer in cattle) may have caused 2.5 million human deaths since 2000.

From Inside Climate News, EVs with a 600-mile range are coming, perhaps in just a few years, thanks to advances in solid-state batteries. The tech will likely arrive in high-end cars at first, then more ordinary vehicles by 2030 or so. And as the author points out,

when a typical EV has more range than a typical gasoline model has with a tank of gas, and when an EV costs about the same or less than its gasoline equivalent, we can begin working on our eulogy for the internal combustion engine.

Two things. First, thanks for the shoutout on my essay about the glacier in the crater of Mount St. Helens. Second, I agree with all you wrote about Barry Lopez. I would also add that his three collections of short stories--Winter Count, River Notes, and Desert Notes--are also wonderful reads.

Beautiful tribute—I’ve been meaning to read Arctic Dreams for years now but it seems to deserve a carving out of attention that is difficult to find!