Hello everyone:

I've just read a beautiful essay, “Heal-All,” by Robin Wall Kimmerer (from the 2017 book Nature, Love, Medicine: Essays on Wildness and Wellness), and want to ask you this: Would you rather talk about life on Earth as a collection of objects, or as a web of interconnected lives and relationships? Easy answer, I imagine.

But what if we defined life here to include inanimate wonders such as stones, rivers, landscapes? What if all animate life and inanimate features of the landscape were granted personhood by the language? Are you comfortable saying of an aphid that "he’s eating the roses" or of an apple tree that "her blossoms shook loose in the wind" or of a river "she flows beautifully"? We do some of this already, I know, most often when we speak with traces of folk traditions on our tongue ("she sails beautifully," we say of a boat) or a sense of poetry, or when from nearly any culture we refer to the Earth as feminine. But the moment we want "accuracy" or "objectivity," we revert to our universal "it."

Gender isn't my point here; my point is acknowledging the erasure we unconsciously inflict by referring to other species as "it." Kimmerer writes in "Heal-All" that

When I'm passing through the meadow on a summer morning and encounter the one who woke me to bird song or the one who gives me my healing tea, when I am on my knees picking Prunella [Heal-All], who faithfully places herself in my path – calling them all "it" feels wrong. The grammar of English reduces the natural world to "things" and thus opens the door to exploitation.

In my native Anishinaabe language it is impossible to speak of plants or animals or rivers or mountains as "it." We refer to them with the same grammar as we do our own families, because they are our families. Because they are understood as persons, we speak of them as persons. We speak with a grammar of animacy.

I'm not writing this week to advocate for a fundamental shift in English; I'd love to see the change, but uprooting the objectifying pronoun from English would be the equivalent of a heart transplant for the language. It will probably be easier to turn petrochemical companies into organic florists. What interests me this week is the worldview Kimmerer – a botanist, ecologist, professor, and member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation – so beautifully articulates from her vantage on the meeting ground between science and indigenous knowledge.

That worldview, the one that understands Heal-All to be a person with a remarkable gift of medicine (antiviral, antibiotic, anti-inflammatory, and more) for other persons, including humans, is based in love. Love of the family we call plants and animals, as she says, but mostly love for the natural world in its complexly woven beauty. Love, Kimmerer says, even in the face of the Anthropocene:

It's risky, though, to love the world, in a time of climate peril. Your heart could get broken. The places and beings we cherish are evaporating before our eyes... But the plant teachers remind us that often the cure grows near to the cause. The cause for the fear and the pain of loss is the love we bear for the land. And love, we know, is the cure for loss, the antidote to fear. Love is the medicine when it changes us, and we change the world.

We can all point to cherished places and beings we’ve lost to the ever-widening human onslaught – childhood forests, family farms, favorite species diminished nearly to the vanishing point – and so we can each speak of our hearts breaking. And there are the images from around the harrowed world arriving day after day, throughout each year, of what Neil Young described a half-century ago as “Mother Nature on the run.” There’s so much devastation, at every level. But in her essay Kimmerer does a fine job of placing the tumult of our fear and loss squarely where it belongs: within the gravitational pull of love.

This is not some plaintive Can’t we all just get along? wishful thinking. This is Kimmerer establishing an ethical framework for our relationship with reality and calling out the ways in which language either undermines or sustains that relationship.

She makes a metaphor of the often-but-not-always true folk truism that remedy plants often grow near the plants which cause harm – like jewelweed near poison ivy – to explain to us that our suffering in the face of these losses is a strong reminder that we still love the natural world, even in the midst of all our civilizational delusions and distractions.

And that’s what I want to write about.

The Greek root “-philia” is attached to nouns to identify, most often, an emotional attachment to that noun. Bibliophilia is a love of books, while Francophiles devote themselves to all things French. (Hemophilia, though, is a tendency to bleed rather than a fondness for blood...) There are shades of meaning here, but –philia is generally defined as love. Let’s lump the shades together – affection, love, tendency, desire, attachment – and apply it to our place in the fabric of life.

E.O. Wilson, a naturalist from earliest childhood, never lost that childlike wonder in the midst of nature. He joined Harvard in 1951, at the same time as James Watson (who along with Francis Crick discovered the structure of the DNA molecule), and held his ground against the prevalent idea that the only biology that mattered was molecular. Studying species was merely a quaint hobby. Wilson knew better, and he prevailed, pushing the study of visible nature in new, brilliant, fascinating directions. Along the way, though, he became haunted by the intensifying loss of species and ecosystems – entire landscapes, really – as human population, agriculture, forestry, and industry expanded at a thoughtless and exponential pace. “Destroying rainforest for economic gain,” Wilson once said, “is like burning a Renaissance painting to cook a meal.”

In Wilson’s lifetime, population nearly quadrupled, from 2 billion in 1929 to 7.9 billion. The start of his career coincided with the beginning of what ecologists have called the Great Acceleration, when human impacts on the web of life shifted from astonishing and bizarre to catastrophic on a geological scale.

In the face of the increased rate of extinctions and rapidly diminishing biodiversity, Wilson worked to remind us that our humanity is not defined by the consumption of industrial goods, televised/digital entertainment, and fossil fuels. Our urban/suburban/indoor lives are increasingly abstracted from the real world, but he knew that our evolution still shows through us like houselights through shuttered windows.

An important part of Wilson’s work was his Biophilia Hypothesis, introduced in his 1984 book Biophilia, which explored in depth the evolutionary and psychological roots of our attraction to the natural environment. Wilson defined biophilia as “the urge to affiliate with other forms of life” or “the connections that human beings subconsciously seek with the rest of life.” Simply put, one or two million years of our hard-fought and hard-earned evolution within the community of life will not be stifled by our recent few centuries of pretending that community doesn’t matter.

This innate love of living things is woven through our lives – from pets and houseplants to bird-watching and stress-reducing walks in city parks – but it’s not simply a matter of appreciating nature like a painting. The hard-wired genetics play out equally in our love of a beautiful forest, our affection for baby meerkat photos, and our phobia of what my mother and sister might call “face-eating” spiders (which to them is pretty much any spider). The deprivation of children (and adults) who suffer “nature deficit disorder” is as real as the joy, astonishment, and resilience they (we) develop when spending hours outside.

When we are within the fabric woven by insects, grasses, animal tracks, birdsong, wind, pollen, amphibians, streams, spider webs, stones, and the architecture of trees and topography, and we are paying attention to the fabric’s details and breadth, we cannot help but feel the stirrings of our pre-Anthropocene lives. We might love it, we might have a million questions to ask of it, or we might feel the uncomfortable weight of the fabric on our urbane self-awareness, but the recognition of the real world is universal.

The real world is full of “magic wells,” as both Wilson and Nobel Prize winner Karl von Frisch knew well. Frisch won the Nobel for discovering the language hidden within the dance of honeybees, and he referred to his bees as a magic well, because no matter how much he discovered, there was always more to learn. (For a very recent dip into the honeybee well, I highly recommend My Garden of a Thousand Bees, a PBS Nature documentary shot lovingly in its filmmaker’s urban garden during the pandemic.)

There’s a beautiful description of Wilson in the opening paragraph of a chapter (“The Biophilic Sublime”) devoted to him in Alan Gross’ 2018 book, The Scientific Sublime: Popular Science Unravels the Mysteries of the Universe. It follows an excerpt from Darwin’s letter home to his sister while in Brazil during the voyage of the Beagle: “Whilst seated on a tree, & eating my luncheon in the sublime solitude of the forest, the pleasure I experience is unspeakable… so that if I gain no other end I shall never want an object of employment & amusement for the rest of my life.” Gross writes:

Sitting in the same rain forest where Darwin penned these words more than a century earlier, E. O. Wilson shares the identical “cathedral feeling,” the identical sense of the biological sublime evoked by the diversity of the biosphere: “Hold[ing] still for long intervals to study a few centimeters of tree trunk or ground, [and] finding some new organism at each shift in focus.” It is a feeling for his fellow creatures exhibited in every aspect of E. O. Wilson’s life: his efforts to understand ant society, his discovery of sociobiology as means of understanding all societies, and, finally, his efforts to preserve the diversity of the biosphere in which all societies must find their place. For Wilson, environmental ethics flows naturally from the cathedral feeling he shares with Darwin, their sense of the biological sublime.

Darwin’s “unspeakable pleasure,” Wilson’s capacity to spend hours observing a handswidth of tropical life, the filmmaker spending months in his garden of a thousand bees, and Kimmerer greeting the Heal-All in her path are all rational, ethical, loving responses to the animate world of which we are an integral part. These wonderful people are the grown-up successors to the children at the magic well. The well, of course, is open to all of us.

Wilson writes in Biophilia of his time in the Brazilian rainforest,

I opened logs and twigs like presents on Christmas morning, entranced by the endless variety of insects and other small creatures that scuttled away to safety. None of these organisms was repulsive to me; each was beautiful, with a name and special meaning.

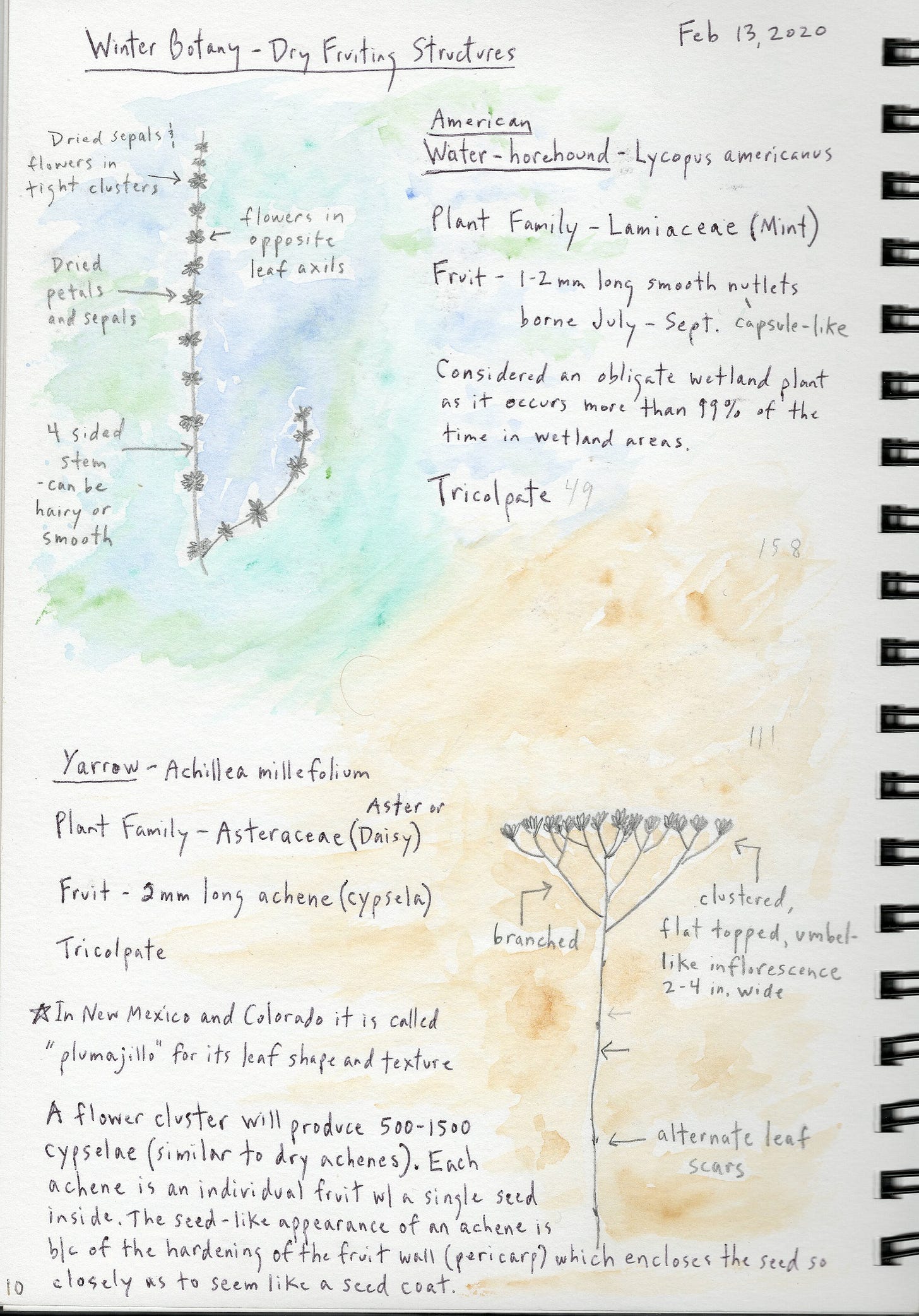

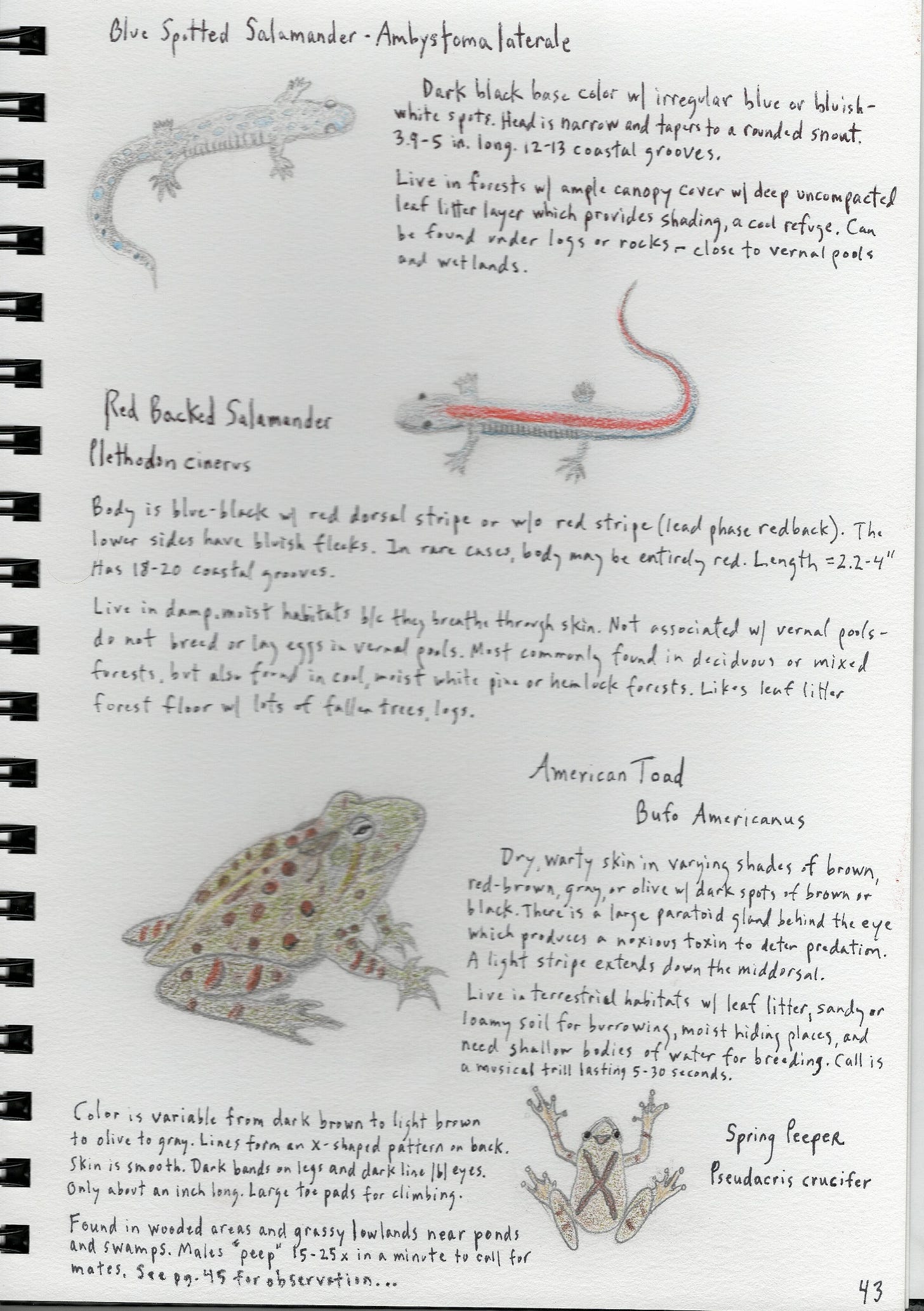

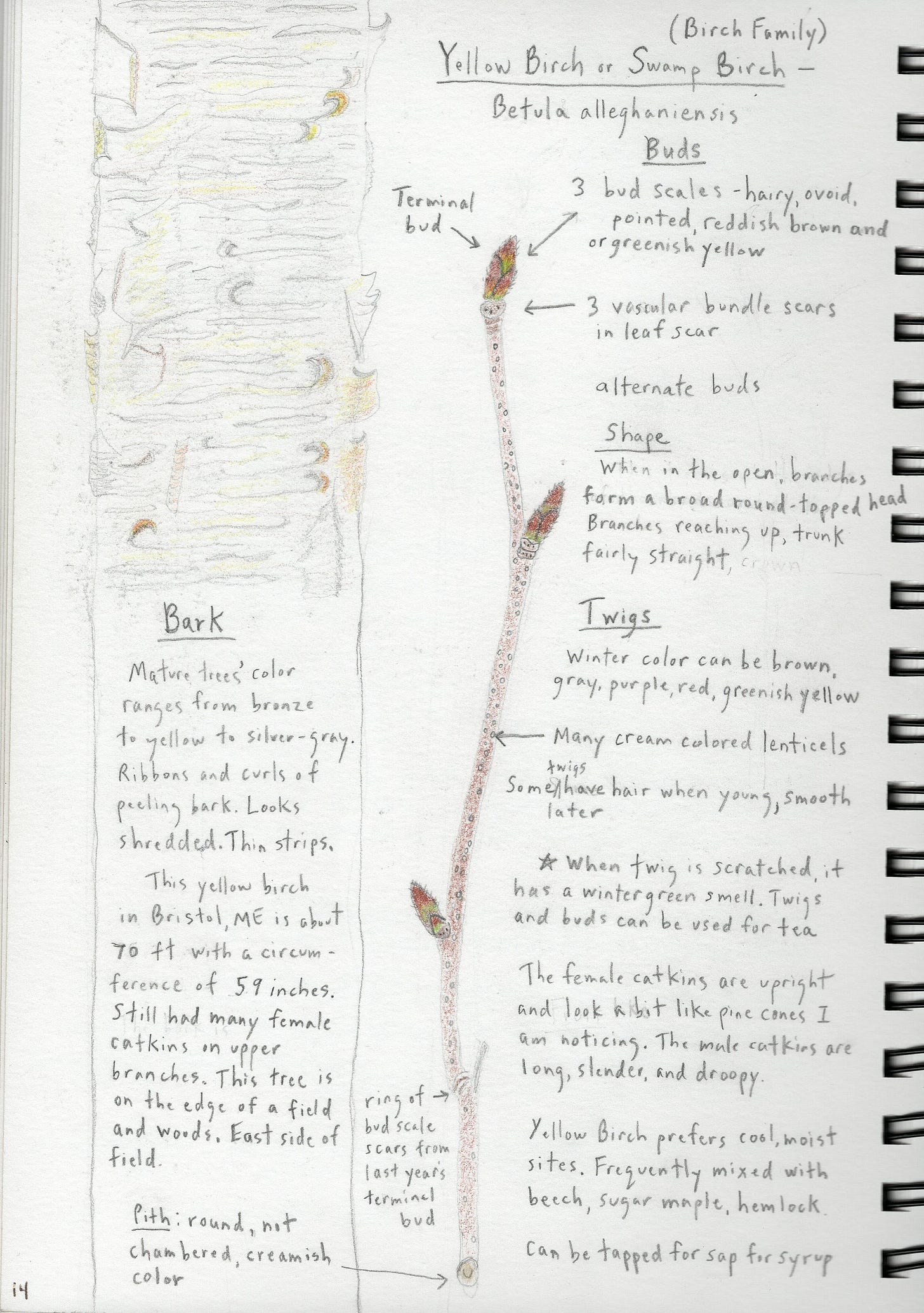

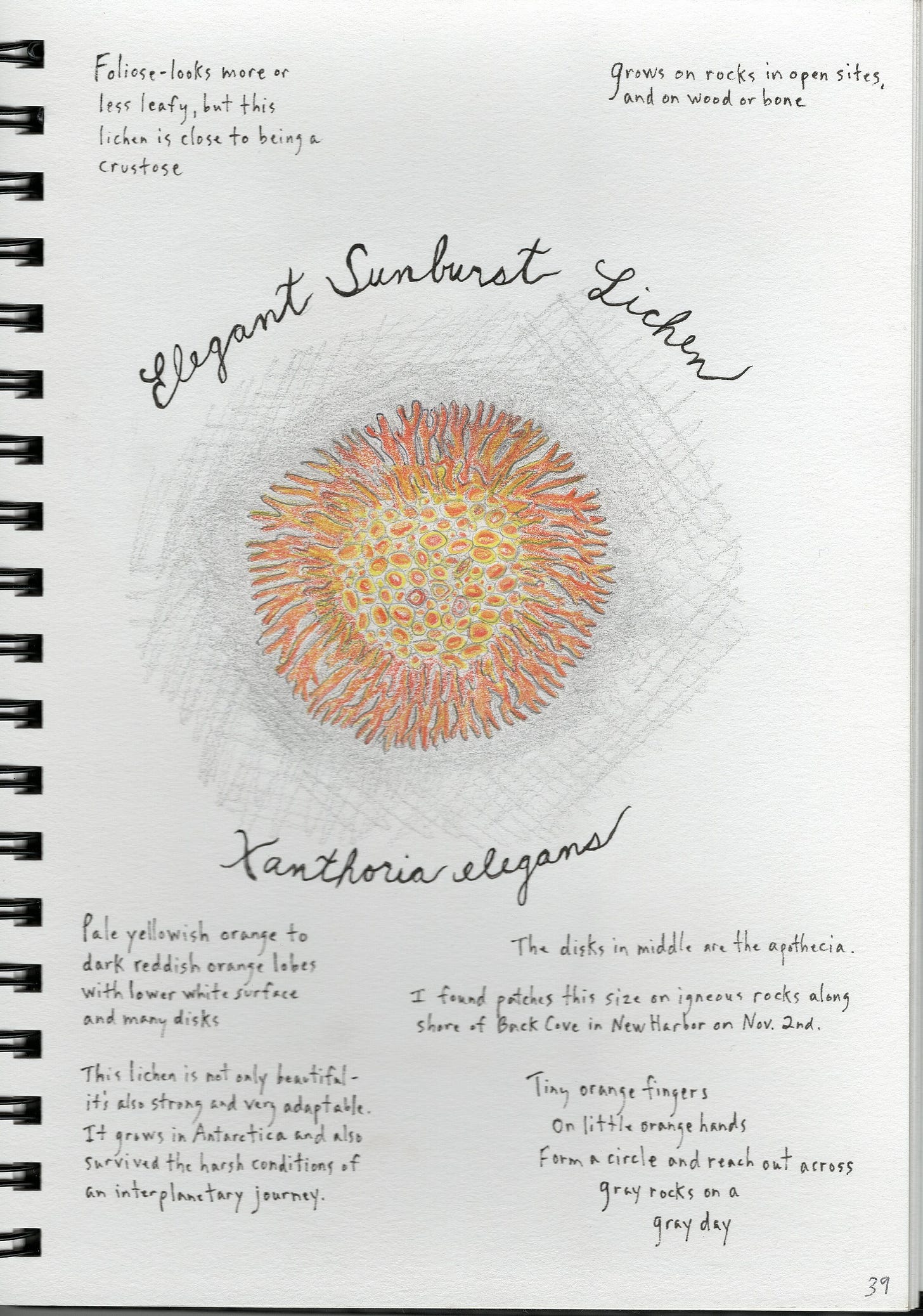

My wife Heather spent 2020 in the Maine Master Naturalist Program, an intensive introduction to the world outside our door here, and as part of her studies filled notebooks with the observations and illustrations you see here. As I described in a previous essay, she and I embarked on journeys of understanding that will continue throughout our lives, finding entertainment and joy in studying the hidden world of lichens and mosses, the vast world of insects, and the interconnected world of forests. And so much more, as you can see from Heather’s notebooks. Part of the genius of the MMNP, too, is that graduates are expected to teach what they learn, as volunteers, in their communities for years to come.

I’ve been writing so far, mostly, of the love that zooms in on the details of life – the child with the ladybug, the naturalist with a magnifying glass – which is our biophilia expressed through careful study of the meaningful lives led by other species. Let’s broaden the picture for a moment to contemplate the ideas of topophilia and ecophilia. Topophilia is the love of place. The term has its origin in a mix of poetics and human geography, but the idea is simple enough, especially if you overlap it with biophilia: we are biologically driven to develop what we think of as our cultural attachment to place. Remember the childhood forest or family farm evaporated by heedless development? Is our attachment and subsequent suffering merely personal? Or is it that we see, like Shakespeare, “books in the running brooks, sermons in stones, and good in everything?”

The idea of topophilia immediately draws up very strong feelings for three different landscapes in my life. Maine is my birthplace and home ground, and when I’ve been away for a while the sulfurous smell of low tide in the midcoast region hits my brain like a perfect piece of chocolate cake. I can feel my body settle happily into itself. (Interestingly, though I spent much of my childhood on Cape Cod – my father was a fisheries scientist in Woods Hole for many years – I have little of the same affection for that landscape. We lived in nice old houses, not far from the water, with a beach just down the road, but the place never registered on my consciousness like Maine.) And I fell deeply in love with Antarctica, a landscape so otherworldly and un-Earth-like that to love it is to be haunted by it. I worked there for most of a decade, and the feeling only grew stronger. Even today, 18 years since I last stepped foot on the ice, images of the ice pull at me with their own lunar gravity. And finally, there’s the place that served as a nexus of Maine and Antarctica for a decade: the South Island of New Zealand. I spent month upon month hiking and exploring, breathing in the air of mountain and rainforest and wild, rugged shorelines. Yes, it’s one of the easiest places in the world to fall in love with, but believe me when I say it became a second home. I might have stayed forever but for the pull of family and the Maine coast.

Ecophilia, the love of our home habitat, can serve as a synonym for biophilia, but I like it instead as an umbrella term for the combination of topophilia and biophilia. We have, I believe, a deeply-written code in our DNA that connects us to life on Earth and, more broadly, to its community landscapes. We’ve been finding meaning in the fabric of life for all but the last few moments of human history, so the revelation here is in the remembering rather than the realizing. If we step off our daily roads and paths and allow ourselves to be embraced by the complexity of the natural world, the love/affection/tendency/desire/attachment should well up.

And with that love comes consequences.

I should close by saying that I’m not particularly caught up with the use of these –philia words. It’s the love and its consequences that I’m after. If we feel and acknowledge the love, then we’re more likely to take action in the midst of the onslaught.

For what it’s worth, the words topophilia and ecophilia barely exist in the language. Even biophilia, if we were to stop people on the street and ask them if they knew the word, would scarcely register. And, to be honest, these –philia words are about as clunky as “Anthropocene.” The words aren’t the point so much as the underlying story about what it means to be human at this time on Earth. They all ask, or answer, the age-old questions: Who are we? What are we doing? What do we need to change?

The Anthropocene poses an astonishing number of threats to what we love. Worse, it makes it harder to develop and feel that love, through the challenges of rogue weather, intense heat, invasive species (ticks!), and an increased fear-driven push to stay indoors. But that’s for another day. For now, it’s about those questions – Who are we? What are we doing? What do we need to change? – and how time well spent in the community of our fellow species can inform our answers.

Thanks for sticking with me.

My last order of business this week is to ask for some feedback. I have a couple questions about the curated Anthropocene news I offer each week. My essays often run long(ish) and have their own set of links to follow. I’m wondering if you feel that the curated news items seem like more information than you want to receive all at once.

I do really enjoy surveying the Anthropocene news landscape and providing links to those articles that seem particularly interesting or important. There’s so much to be included in our mental and emotional map of the world as it changes, and I like to think that some surprising story will be revelatory for one or more of you, as they often are for me. But there’s a lot of news out there and I don’t want to overwhelm you.

Also, I’d be curious for a vote on whether the curated articles should be focused on solutions-oriented news rather than the usual mix of describing-the-problem and working-to-solve-the-problem. I ask because at some point we have to stop being the fire alarm and work on becoming the fire extinguisher…

So then, here are the questions:

Should the curated Anthropocene news items be

spun off into a separate email sent to your inbox on, say, Sunday or Monday evenings?

discontinued altogether?

kept as they are?

changed in some other way?

Should the curated Anthropocene news items be focused on solutions?

Please let me know what you think in the comments, or send me a direct response by email. Thanks in advance for the feedback.

I loved this essay, and I greatly appreciate your inclusion of curated news, external references and links. Also, a group of us in the Boothbay Region have just started the Boothbay Region Clean Drinking Water Initiative. We have big plans for her Majesty Fresh Water.

Loved this essay. And I love the curated news, and I don't want you to change the content, as long as it includes at least one solution each time. You COULD post it on a separate day, just to make your posts a little shorter....

I love what you're doing with this platform, and I've just posted this essay to Facebook. And the images are lovely.