Hello everyone:

This week I’m finally offering a piece that has been simmering for a while, a fully rewritten essay from two years ago. Perhaps I should be talking about the crises of the visible world - the violent swirling of hurricanes and politics - but am instead inviting you behind the biological curtain into the world of microbes, whose planet this really is.

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read some curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

“The problem with environmentalists, Lynn Margulis used to say, is that they think conservation has something to do with biological reality.” This was writer Charles Mann in a wonderful wide-ranging essay from Orion in 2012, citing the famed evolutionary microbiologist Margulis as he pondered the fate of humanity. Margulis’ point was that what we think of as the dominant lifeforms on the planet - lions and tigers and bears, oh my - are largely irrelevant in the history of life.

“She couldn’t help regarding conservationists’ preoccupation with the fate of birds, mammals, and plants,” Mann explained, “as evidence of their ignorance about the greatest source of evolutionary creativity” on Earth: microbes. More than 3.5 billion years ago, for example, bacteria pioneered all of the chemical systems essential for life. Cyanobacteria learned to eat light and produce the oxygen-rich atmosphere that fostered what we think of as the living world. Many of the fundamental internal structures - mitochondria, chloroplasts, tools for magnetic navigation - in the cells of larger organisms like us are the result of endosymbiosis, when one microbe early in Earth history permanently absorbed and made use of another. “As humans,” an Ecotone article reminds us, “our evolution is entirely dependent on one bacteria’s failed meal.”

Her contribution to endosymbiotic theory was one of Lynn Margulis’ great accomplishments. Another was “convincing her colleagues that [life] did not consist of two kingdoms (plants and animals), but five or even six (plants, animals, fungi, protists, and two types of bacteria).” Margulis knew that having set the stage and parameters for the living world, microbes are for all practical purposes our creators, the tiny ubiquitous gods responsible for nearly everything that happens both outside and inside the bodies of larger creatures. More than 90% of living biomass on the planet consist of microorganisms, and “compared to that power and diversity,” Mann writes, “pandas and polar bears were biological epiphenomena - interesting and fun, perhaps, but not actually significant.”

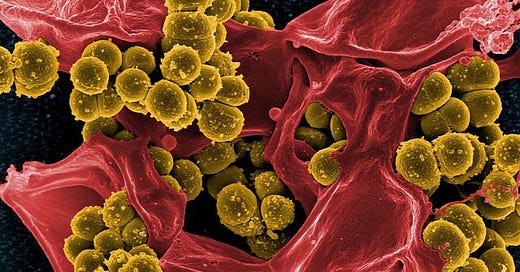

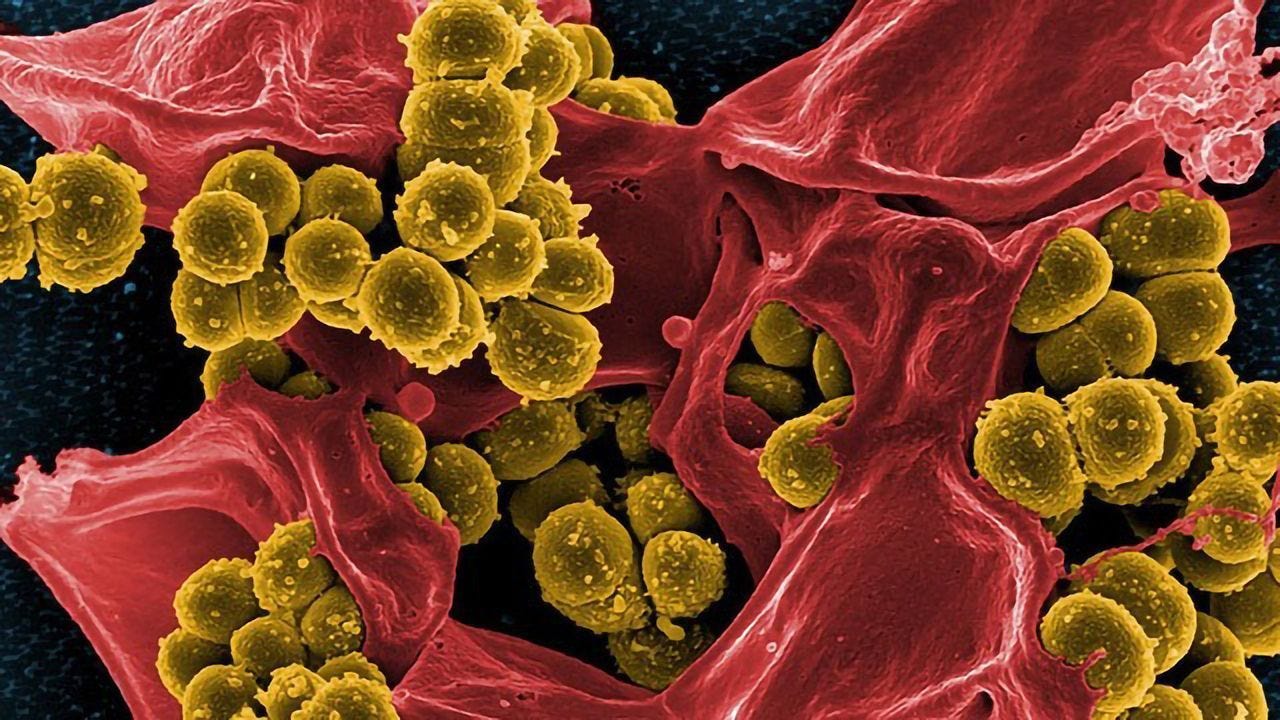

Margulis once told another interviewer that “we tend to associate the word bacteria or microbe with disease, when they are just life!” We are all, she said, “walking bags of bacteria.” A more diplomatic way of saying this is that each of us is more community than individual. Our bodies contain more microbial cells (about 39 trillion) than human ones (30 trillion), though the microbes make up only 1%-3% of our mass. The diseases and pandemics that erupt out of our still ill-defined relationships with viruses, fungi, and bacteria are simply part of the planetary game they designed, shaping not just our social history but our genomes too.

Once we start to glimpse the scale of the actual world - built and run by microbial life - it can be disorienting. “Everything about microscopic life is terribly upsetting,” wrote science fiction writer Isaac Asimov. “How can things so small be so important?”

Not just important, but strange and powerful. In just one example, Bdellovibrio, a predatory bacteria and merely one of the approximately trillion species of microbes, might be the planet’s fastest organism. When hunting other bacteria, it can move about 600 times its body length per second. A cheetah, for comparison, accelerates to about 16 body lengths per second.

Microbes were the first life to evolve and will be the last life standing, no matter what happens to the Earth. Today, they still drive the biogeochemical cycles (carbon and nitrogen especially) that control conditions for life. At least half of Earth’s oxygen is produced by photosynthesizing bacteria in the oceans. If none of this large-scale reality intrigues you, then bear this in mind: microbes (specifically yeasts) make all of our bread, beer, and cheese… plus wine, vinegar, yogurt, miso, tofu, and about 3500 other fermented foods cultured by cultures around the world.

Some microorganisms can lay dormant in Antarctic ice for a hundred million years before cheerfully waking up to get back to work. Some are so hardy that if they hitched a ride to Mars, where billionaire dreams will soon go to die, they have a chance of surviving. There are plenty of bacteria here, for example, that live only on sulfur products. Provide them a little nitrogen and trace amounts of water and they might be happy Martian colonists for a while.

For now, though, Earth is their planet, not ours. The great biologist and naturalist E.O. Wilson famously described insects as “the little things that run the world,” but I think that insects would agree that they’re one level up from the real bosses. These littler things that really pull the planet’s strings are far more numerous and varied than we have even begun to grasp. One estimate suggests we’ve identified only 0.001% of the estimated trillion microbial species.

Noted paleontologist and writer Steven Jay Gould once said that “we should forget about the Age of Dinosaurs, forget about the Age of Man - we’ve always lived in the Age of Bacteria.” Unlike us and giant reptiles, microorganisms are as enduring as they are pervasive and ubiquitous. This is one more reason to suggest that naming the current epoch the Anthropocene is an act of hubris. But hubris is how we got here, so maybe it’s appropriate.

And that brings me to my two points about the “microbial Anthropocene”: When we transform the little things that run the world, we transform the world. And conversely, when we transform the world by setting the conditions for the sixth mass extinction in Earth history, we’re upending the vast, largely unseen, microbial world too.

To make my first point, I’ll introduce the idea of the microbial Anthropocene by explaining yet another astonishing ability of microbes: horizontal gene transfer (HGT). HGT allows genetic material to be passed “horizontally” between individuals of a species and, more importantly, individuals of different species, rather than “vertically” in the succession of generations. Think of it as handing a toolbox to a friend or family member rather than waiting for a child to grow up and inherit it.

HGT is a rapid evolutionary workaround that avoids the time necessary to pass on DNA from generation to generation until mutations arise that improve the species. (This happens in a variety of ways, which I don’t have the space or knowledge to explain, but if you want to dive in you could start with this simple but clear video and then try parsing a very thorough Wikipedia page.) The genes acquired through HGT, if useful, are then passed on as DNA or via HGT to another microbe.

I mention HGT because it’s the common strategy by which microbes acquire antibiotic and vaccine resistance, learn to consume man-made chemicals like pesticides and petroleum pollutants, pass on traits that increase their virulence amid dense populations of people and livestock, and respond to the impacts of a changing climate.

Watch the short video here to witness bacteria evolve in just several days to thrive on exponentially increasing amounts of antibiotics. (Turn on the audio for an explanation by one of the researchers.) Note, though, that in this giant Petri dish, as in rivers and sewer systems around the world, we’re not creating these antibiotic-resistant bacteria. We’re selecting for them by creating a world in which they can thrive.

As an illustration of my second point, there’s the hidden tragedy behind the tragedy of habitat loss. The Anthropocene, we should remember, is as much about erasure as transformation. As wildlife populations decline, as forests and seagrass meadows disappear, and as wetlands fall to the plow, so too do the vast microbial communities associated with them. Gone are the unmapped microbiomes in the bodies of the disappeared and in the habitats that held them. Extinctions never happen to just one species. They happen in bulk because no complex life form is an individual. When the golden toad of Costa Rica and the Kauaʻi ʻakialoa of Hawai’i went extinct, so did any microbes and microbial relationships specific to their species.

Which is why, with all due respect to the extraordinary genius of Lynn Margulis, wildlife conservation is in fact deeply relevant to biology on Earth. (To be clear, Margulis supported conservation, but wished we understood the deeper biology behind the curtains of fur, feathers, skin, and scales.) If we protect species, habitats, ecosystems, etc., we’re also protecting the microbial worlds they contain.

We’re disrupting the world that microbes built with a force that in some ways rivals theirs. The atmosphere is hotter and the ocean is 30% more acidic. The Haber-Bosch process behind the production of artificial nitrogen for fertilizer has changed the chemical composition of the earth, “a feat previously reserved for microorganisms,” wrote Mann. Industrial agriculture has turned much of the planet into a fertilizer-, pesticide-, and herbicide-soaked Petri dish. Our well-fed population has surged to the edge of that dish.

Humans have been extraordinarily successful, but Margulis saw a biological cautionary tale from her life among microbes: “the fate of every successful species is to wipe itself out.” To make her point, she described the growth rate of the bacteria Proteus vulgaris if fed without interruption:

In just thirty-six hours, she said, this single bacterium could cover the entire planet in a foot-deep layer of single-celled ooze. Twelve hours after that, it would create a living ball of bacteria the size of the earth.

But of course Proteus vulgaris is kept in check by the evolutionary forces that surround it. Are we? The bad news is that we’ve eliminated many of the forces which kept our naked ape ancestors in check, but the good news is that unlike bacteria we have the conscious capacity (if not the demonstrated ability) to practice restraint. To avert the worst of the catastrophe that awaits the charismatic epiphenomena we know as plants and animals, and to alter the course of civilization, Mann says, our task is to wisely plan ahead, “but that’s like asking healthy, happy sixteen-year-olds to write living wills.”

The world still very much belongs to the littlest things. But we are, though a combination of ignorance and arrogance, driving many aspects of microbial evolution. Because of the speed of our planetary disruption, evolution in the Anthropocene isn’t the slow Darwinian fluctuation in the size of finches’ beaks; it’s more like the bacteria in the video above, normalizing toxicity at an accelerating pace.

Despite our delusions about living on Mars, our Anthropocene journey isn’t a journey across space. It’s an acceleration of time, the time it takes to create an unfamiliar planet.

We’re burning the maps of our path back to the norms of the Earth that nurtured us. The farther we travel while emitting greenhouse gases, erasing ecosystems, overexploiting animals and plants who need to live their own lives, and spreading toxic chemistry across the globe, the more of the map we burn and the harder it will be to return living conditions on the planet to a semblance of home.

Here’s a slightly calmer way to say all of that, from a 2014 scientific paper called Microbiology of the Anthropocene:

As the Anthropocene unfolds, environmental instability will trigger episodes of directional natural selection in microbial populations, adding to contemporary effects that already include changes to the human microbiome; intense selection for antimicrobial resistance; alterations to microbial carbon and nitrogen cycles; accelerated dispersal of microorganisms and disease agents; and selection for altered pH and temperature tolerance. Microbial evolution is currently keeping pace with the environmental changes wrought by humanity.

Note, though, that the language hides a level of concern that I’m guessing is not much different than my own. “Directional natural selection” is another way of describing our intense narrowing of microbial life’s options. Alterations of the carbon and nitrogen cycles is the equivalent of messing with the life support systems on a spaceship. And “selection for altered pH and temperature tolerance” is a polite way of describing the tragedies of an acidifying ocean and a hotter atmosphere, both of which have been key components of Earth’s previous mass extinction events.

And here’s a graphic from that paper:

The graphic is smarter than I am, so there’s a lot I won’t try to unpack, but in brief the authors selected a half dozen categories of Anthropocene impacts (listed down the left side) and mapped the growth of those impacts through human history (from left to right). They’ve chosen the dawn of the industrial revolution as a starting point for the Anthropocene, but have noted two other candidates for that starting point: the beginning of large-scale agriculture and our overhunting of tasty megafauna about 10,000 years ago (which they cleverly call the Paleoanthropocene), and the Great Acceleration in the twentieth century when our population and impacts radically intensified. You’ll see in the graphic that when we reached the Great Acceleration the impacts multiplied and worsened.

The logarithmic scale here is important enough that your jaw should be at least a little closer to the floor. Like the antibiotic resistance video above, this is a portrait of exponential growth, in this case with each time interval at the bottom of the image ten times shorter than the interval before it.

Most of our shifting of microbiological evolution and planetary dynamics has occurred in just the last century – a time span scarcely measurable in Earth history – which means we are playing God with this planet less like an omniscient overseer and more like the drunk driver of a big rig going the wrong way on a highway full of school buses. We are in no way equipped to be deities, particularly to the far more adapted and god-like microbes.

In her masterful Braiding Sweetgrass, Robin Wall Kimmerer notes that humans are more accurately described by numerous Native American traditions as a younger sibling to the species around us. Those traditions understand that plants and animals have been here far longer than we have, and so already know how to live, whereas because of our particular type of consciousness, we’re still learning. Or we were still learning, until our invention of lunatic capitalist industrialism convinced us we could drive anywhere we wanted.

I’ve leaned a little hard into the problem side of the equation this week, so I’ll end with a reminder that an astonishing number of humans are doing an astonishing amount of beautiful work - both paid and volunteer - to preserve, protect, adapt, and rewild the living world, every day. There are a few great examples in the curated Anthropocene news below, as always, and you can subscribe to a) Sam Matey’s Weekly Anthropocene for an enthusiastic global survey of good work being done to counteract the climate and biodiversity crises, and b) Mike Shanahan’s Global Nature Beat for the most comprehensive round-up of biodiversity- and conservation-related news you’ll find anywhere.

Yes, they’re both focused on charismatic biological epiphenomena (including us) rather than microbes, but now you know, while reading about sea turtles and endangered parrots, that in and around and behind the curtains of skin, fur, and feather are hidden living worlds as well. We scarcely understand these communities and their innumerable intricate relationships, but we owe them our lives. The multitudes contain multitudes.

This knowledge makes wildlife conservation and environmental protection even more beautiful, doesn’t it? There’s so much more at stake than what we can see.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

From

and her What If We Get It Right?, “Vote Climate,” a podcast that discusses why 8 million environmental voters sat out the 2020 election and what should be done about it this year.In other vital election-related environmental news, from Mongabay, new polling suggests that Americans are actually united around the importance of conservation and protection of wildlife. 87% (including 82% of Republicans) say a candidate’s position on environmental protection will help determine their vote. 83% of Republicans and 93% of Democrats believe the federal government should do more to strengthen the Endangered Species Act. The numbers are good and rising on climate change as well. Someone needs to tell V.P. Kamala Harris’ team to start talking about wildlife conservation. Advocating for RAWA (Restoring America’s Wildlife Act) would be a great place to start.

Also from Mongabay, an important interview with Dr. Gary Shapiro, who has worked to study, communicate with, and protect orangutans for five decades. Shapiro believes firmly that these highly intelligent and emotionally complex beings deserve legal personhood. He is the co-founder of the Orang Utan Republik Foundation. His new book, Out of the Cage: My Half Century Journey from Curiosity to Concern for Indonesia’s “Persons of the Forest,

offers not only a personal account of his groundbreaking research but also a call to action for the conservation of one of the world’s most endangered species. As the book’s release coincides with the ongoing struggle to preserve the rainforests of Southeast Asia, Shapiro’s message is clear: the survival of orangutans is a test of humanity’s willingness to protect the natural world that sustains us all.

From

and his Global Nature Beat, “Tides of Survival,” a lovely story and a heartfelt plea to support the volunteer turtle protectors of Trinidad, who patrol the beaches at night through the spring and summer to help secure the futures of the adults who come ashore to lay eggs and the young who hatch and wiggle their way toward the troubled seas of the Anthropocene. Mike and his son bear witness to the hard work being done by people who could use our support.From

and The Weekly Anthropocene, another good-news great-work interview with Victor Mwanga, CEO of EarthLungs Reforestation Foundation, which is doing astonishing work planting trees in Kenya and Tanzania. The benefits are as much social and economic as they are ecological.From the Guardian, a great story I’ve highlighted before but is worth updating now. Salmon are running free up the Klamath River in Oregon for the first time in a hundred years, now that a series of large dams have been removed. In fact, the salmon were seen moving past the site of the final dam removal just days after it was completed.

Also from the Guardian, a deeply disturbing and entirely unsurprising report on the more than 3,600 chemicals approved for use in food packaging that are now found in human bodies. Plastics are by far the worst offenders. Little is known about the impacts because very little has been effectively studied. We live in a world in which constant toxic exposures are approved because short-term industrial profits take priority over long-term public health.

From Hakai, equally disturbing but far-less-known research has found that migrating birds are carrying PFAS “forever” chemicals from the polluted lower latitudes into the remote Arctic.

From Mother Jones, despite the myths put out by the fossil fuel industry, when we export methane (euphemistically known as “natural gas”) it has a dirtier carbon footprint than coal.

From Carbon Brief, “How the U.K. Became the First G7 Power to Phase Out Coal Power,” an excellent historical overview of how the nation that pioneered coal energy is now the first to get rid of it.

Jason, this is one of your best and most important articles yet. This is critical information, and yet very few people (including many scientists) seem to be blissfully unaware of it. And this is why I say that any hope of ever colonizing another planet is completely dashed. If the planet is dead, it's because it cannot support life, and there would be good reasons for that which we couldn't fix. If there's life, it will be mostly microbial, and if it's DNA-based (which is likely), the newly arrived humans will be like a special treat. We would have zero resistance and wouldn't last a week. It's fun to write about or make movies about visiting other planets in science fiction, but it's highly unlikely it could never happen in reality. Anyway, I shared your piece on Facebook.

Another keeper — I am so grateful for it.

!!>> “The multitudes contain multitudes.” <<!!