Hello everyone:

Please remember to respond to my two-question survey from last week’s essay. I’d like to know your thoughts on the future of my curated Anthropocene news section. I’ll repeat the survey at the bottom of this page. Thank you for taking a moment to respond.

Now on to this week’s essay.

When I began writing this Field Guide nine months ago, I joined the global chorus of Cassandras. That is, I joined the growing network of people who can see that the difficult future awaiting much of life on Earth has already begun to arrive, who understand that wealth-driven human behavior is the cause, and who know that the worst of this future was (and still is) avoidable, but whose analysis has not been fully understood or embraced by civilization. This vision of the unmitigated future – we can call it “prophecy” to align with the Cassandra story – is a bitter, jagged pill to swallow for a seemingly flourishing civilization.

As with so much of Greek mythology, there are very different versions of Cassandra’s story, but the heart of it for our purpose here is that she was a daughter of the king and queen of Troy, and so beautiful that the god Apollo fell in love with her. He offered Cassandra the gift of prophecy in exchange for her love. The gift was hers, but she could not (or would not, according to the playwright Aeschylus) return the affection. An aggrieved Apollo couldn’t undo the gift, but he poisoned it with the curse that Cassandra would never be believed, regardless of the truth of her words. Thereafter, her family and the Trojan people thought her a liar or insane.

In today’s global community of Cassandras I play a tiny role – turning phrases more than planting trees or changing minds – but it’s still a task worth doing if it turns up the motivation dial a little. The threats to the community of life which has sustained us through our evolution desperately need our attention and awareness, and I’m happy to do what I can.

It’s a full circle of sorts for me. At age 19 I realized, much to my surprise, that I wanted to be a writer. I had taken a semester away from college to hike on the Appalachian Trail. My interest was poetry then, not prose, but those months living both in the woods and in my head as I walked started me on a path of writing at the intersection of consciousness and the natural world we have largely retreated from. My years in Antarctica shifted me from poetry to lyrical prose that struggled, lovingly, with a landscape that scarcely responded to language. Then, by happenstance, I ended up writing an odd history of Antarctica that explored the human experience of the ice – cleverly disguised as a “culinary history” of a continent with no cuisine – but to do that I had to teach myself how to write regular narrative and push the poetry to the corners of my sentences. By then I had landed back here in Maine to reconnect, season after season, with my home landscape.

My family, a few years back, got gobsmacked by a huge, foolish, unnecessary, ill-designed and ecologically harmful development next door to the farmhouse. What had been a quiet patch of woods was being turned into 24 acres of parking lots for a popular botanical garden that suddenly had Disneyland ambitions and predatory management. (It’s a long story that I’ll write about sometime. I can tell you already that the essay will likely be titled “Down the Garden Path.”) My family and our allies fought a long, losing battle against lots of money, lawyers, and public opinion in a small town that had mistaken a golden calf for a golden goose.

That process was very bruising for a bunch of reasons, but one of my realizations was that if even a “green” organization in a nature-loving state could be so blind as to unapologetically wipe out a large swath of habitat crucial to half a dozen wetlands, and to increase the risk of nutrient overload for the town water supply, then there was a lot of work to be done to articulate the basics of the Anthropocene. I was haunted also by the disinterested silence in town meetings that greeted what I knew to be really clear statements of the science and the risks and the wrongs. We had become Cassandras, and it wasn’t a good feeling.

Not that it compares to the catalogue of wretched misery that was Cassandra’s life after Apollo’s curse: the slaughter of Troy and her family by the Greeks, rape, captive mistress to Agamemnon, and finally her murder by his wife, all while knowing much of what would happen. The power of her story is in that tragic combination of deep insight and deeper helplessness amidst horrors.

It’s a tragedy that in various iterations has befallen countless women throughout history, women who spoke truth to power or, more often, who simply fell victim to men’s rules, men’s wars, men’s rage, a community’s deafness, or a nation’s fear. Here in the early Anthropocene it’s important to note that for all of our planet-torqueing habits the threats to life on Earth have been accompanied by a slow, steady improvement in the fate of women and girls. It’s also worth noting that continuing and accelerating those social trends – universal access to education, financial investment, family planning, etc. – are key to unwinding much of the Anthropocene.

Today, at least, we’re part of an audience of tens of millions of people who heard young Greta Thunberg accurately critique the weak COP 26 pledges of carbon-neutrality as “blah, blah, blah.” Women lead government ministries, NGOs, protests, community groups; women write the books and gather the data. On that topic, I recommend an excellent recent Reuters long-form profile, “The Cassandra,” on Australian climatologist Julie Arblaster. At the start of the austral summer in late 2019, her analysis of weather patterns around Antarctica led her to predict a high risk of a bad fire season in Australia, a country whose government has been far more interested in selling coal than listening to the scientists. Within a few weeks, though, the country was ablaze.

The profile is fascinating, providing a private portrait within the grand public discussion about the fate of the planet. Arblaster is reluctant to speak publicly with much energy, self-censoring in part because of her shy nature and in part because of how tough the government has been on climate Cassandras. (This piece is part of a six-part series based on the Reuters Hot List of the 1000 “most influential” climate scientists, only one in seven of which are women, highlighting the slow-to-close gender gap in academics and science.) As a bit of a historical follow-up, you might read Paul Krugman’s 2009 op-ed in the Times titled “Cassandras of Climate.”

And then there’s the current film Don't Look Up, directed by Adam McKay and starring Jennifer Lawrence and Leonardo DiCaprio as ordinary, in-the-trenches astrophysicists who find a planet-killing asteroid is headed our way. In a darkly funny and depressingly relevant dramedy, they become asteroid Cassandras struggling to get their message out in a hypermediated world glutted with information but starved of truth. The story serves as an analogy for the fight to bring the climate battle to the center of political and public attention, of course, but it’s also a proxy for the larger problem of putting science – not just technology – at the heart of culture.

The movie reminds me of another possible reading of Apollo’s curse. It’s not necessarily that Cassandra isn’t believed, but that no matter how accurately she divines a tragic future nothing will be done to avoid it. People might understand or even agree with her, but that’s it. This interpretation is both spookier and more relevant to our time, because it speaks to apathy rather than antipathy. 29% of Americans, for example, don’t believe that climate change is important to them personally. Cassandra might feel Apollo’s cruelty when an audience consistently has irrational reactions to her predictions, but if people understand and empathize but refuse to show concern? That’s a curse.

I also recommend two excellent books by friends of mine: Wake, Siren: Ovid Resung is a brilliant reimagining of Ovid’s Metamorphoses by Nina MacLaughlin, each short piece written from the perspective of its previously voiceless female characters, and American Breakdown: Our Ailing Nation, My Body’s Revolt, and the Nineteenth-Century Woman Who Brought Me Back to Life, forthcoming from Harper Wave in March, 2023, is Jennifer Lunden’s groundbreaking memoir and deeply-researched history of industrial capitalism’s impact on the human body, which, unsurprisingly, has suffered in parallel with the Earth. (I’ll highlight Lunden’s book next year when it’s ready to launch.)

I’ve read that in Aeschylus’ play Agamemnon, Cassandra is depicted as having retreated into a despair that resembles madness and that even the chorus – which in these ancient Greek plays is meant to narrate and comment on the action – could not understand her story. She stands alone onstage, silent and ignored, before speaking of her fate in a “mad scene” which falls on deaf ears. Now alone in the world, a victim of Apollo’s malice, she moves offstage to the death she knows is coming at the hand of Clytemnestra.

It’s worth remembering that a Cassandra – the voice with a stark prophetic warning – is merely a conspiracy theorist unless she speaks the truth. Prophecy is a rare commodity, after all. (The fundamental narrative of Apollo’s curse on Cassandra, however unfair and misogynistic, strikes me as a storytelling necessity; what good is a character who knows what will happen and convinces everyone every time?) There’s plenty of easy prophecy to go around; the more experience we have, the more we can see around the corner. When a drunk veers toward the pond, or the George W. Bush administration veers toward Iraq in an illegitimate and half-witted geopolitical ploy to control the Middle East, we can be horrified at the obvious mistake or say, with Gene Wilder’s mock concern in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, “Stop. Don’t. Come back,” because we know it’s too late.

For the climate and biodiversity crises, the truth is pretty straightforward. The benefit, if we can call it that, of the decades-long misinformation and disinformation campaigns against climate science and basic ecology is that the data and the models and the analysis are now ridiculously strong. It’s beyond sad that a couple generations of scientists and activists have had to grovel in the court of public opinion while simultaneously developing incredibly robust science that the public still scarcely acknowledges or understands.

But here we are at this point in history, where the prophecy is irrefutable. We’re bearing witness to ocean acidification, intensified chaos in storm systems, a thousand-fold increase in the extinction rate, Arctic permafrost thawing, the destabilizing of Antarctic ice shelves, the rapid depletion of biodiversity in the world’s remaining coral reefs and tropical forests, and so much more. The basic outline of all these observations was available decades ago. We don’t know exactly how things will play out, given variables like undefined ecological tipping points or the possibility of effective large-scale human action, but Cassandra didn’t know all the details of the Trojan War either, just that if her brother Paris went to Sparta to carry off Helen, the war and Troy’s destruction were inevitable. As Alan AtKisson wrote about our environmental dilemma in Believing Cassandra: An Optimist Looks at a Pessimist's World,

Too often we watch helplessly, as Cassandra did, while the soldiers emerge from the Trojan horse just as foreseen and wreak their predicted havoc. Worse, Cassandra's dilemma has seemed to grow more inescapable even as the chorus of Cassandras has grown larger.

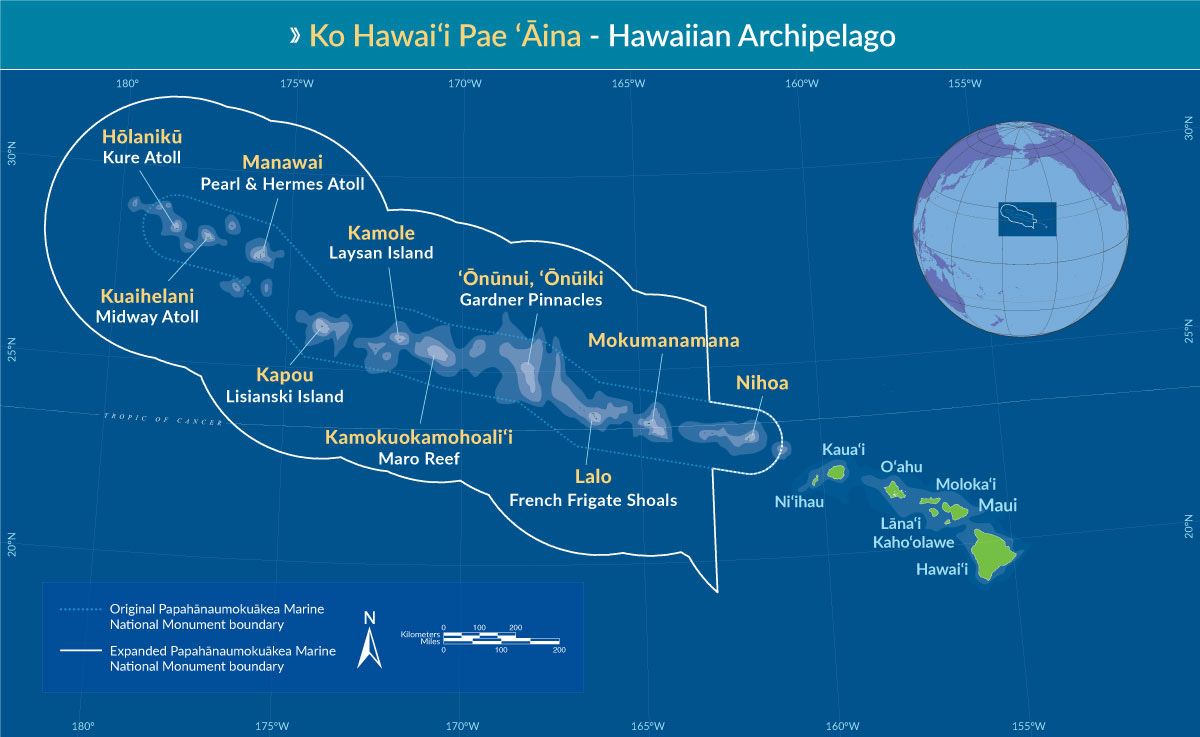

Yet there are victories everywhere for the Cassandras of climate and ecology. Much of the good news is still promissory – think of the recent COP 26 for climate and the 30x30 push (to preserve 30% of Earth by 2030) for biodiversity – but many of the wins are momentous: the massive Ross Sea Marine Protected Area in Antarctic waters and the U.S. Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument in the Pacific, the Paris Agreement from COP 21, the comprehensive science of the U.N.’s International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), etc. Perhaps the greatest achievement and the greatest promise, though, is in the growing network of Cassandras itself. From the scientists, indigenous activists, environmental groups, academics, and government officials who spend every day pushing the slow barge of civilization in a better direction to the voters, protesters, naturalists, teachers, writers, artists, and local organizers who learn the science and echo the call, the chorus is larger and more forceful by the day.

And that’s the point. That’s how we rescue Cassandra from her fate. When the audience chooses to become Cassandras too – learning the science and echoing the call – then the path toward no Cassandras opens wider. The mortals finally see through Apollo’s selfish machinations. The stark prophecy becomes common knowledge, and the work to avoid it becomes the task at hand.

As Arundhati Roy, the great writer and activist, put it, “Another world is not only possible, she is on her way. On a quiet day, I can hear her breathing.”

Thanks for sticking with me.

In curated Anthropocene news:

A jihad against AI: Here’s a brilliant and fascinating essay unpacking the arguments against allowing the development of a “strong AI” (i.e. an artificial intelligence resembling the human mind). While this may seem unrelated to the Anthropocene, I think it speaks directly to the dangerous tendencies of the last few centuries, and I think we should be imagining how AI will increasingly shape society as we push deeper into the 21st century.

Here, there, and everywhere: This one’s a doozy. From the Times, a comprehensive and interactive piece on how climate change is already impacting 193 nations. Each gets its own story, often with video and audio.

Two 2021 climate and biodiversity news retrospectives: from Mother Jones and from SciTech Daily.

Record-breaking record-breaking: from the Times, temperature records (heat and cold) in the U.S. were broken in huge numbers this past year.

Need to store energy without batteries? Gravity to the rescue! Maybe, says Wired, in a really interesting article.

My last order of business this week is to ask for some feedback. I have a couple questions about the curated Anthropocene news I offer each week. My essays often run long(ish) and have their own set of links to follow. I’m wondering if you feel that the curated news items seem like more information than you want to receive all at once.

I do really enjoy surveying the Anthropocene news landscape and providing links to those articles that seem particularly interesting or important. There’s so much to be included in our mental and emotional map of the world as it changes, and I like to think that some surprising story will be revelatory for one or more of you, as they often are for me. But there’s a lot of news out there and I don’t want to overwhelm you.

Also, I’d be curious for a vote on whether the curated articles should be focused on solutions-oriented news rather than the usual mix of describing-the-problem and working-to-solve-the-problem. I ask because at some point we have to stop being the fire alarm and work on becoming the fire extinguisher…

So then, here are the questions:

Should the curated Anthropocene news items be

spun off into a separate email sent to your inbox on, say, Sunday or Monday evenings?

discontinued altogether?

kept as they are?

changed in some other way?

Should the curated Anthropocene news items be focused on solutions?

Please let me know what you think in the comments, or send me a direct response by email. Thanks in advance for the feedback.

What a great essay. I just started an ocean-focused newsletter and have been writing about the most recent IPCC report. It seems that most scientists nowadays are Cassandras, and very few politicians/leaders have the courage to break the curse. You can check it out here: https://incirculation.substack.com/p/ipcsea-part-1?s=w