Hello everyone:

For those of you looking for recent insight into the future of Ukraine’s existential fight against the Russian invasion, once again I recommend Timothy Snyder’s expert perspective.

One final reminder: I’ll be part of a panel, Writing the Natural World, at the Maine Lit Fest in Portland’s Monument Square this Saturday, joining with writers Jennifer Lunden, Gregory Brown, Samaa Abdurraqib, and our moderator Kathryn Miles. Start time is 2:50 p.m.

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read some curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

In thinking about the fate of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS) this week, I suddenly remembered the proverbial phrase “for want of a nail.” The phrase and idea go back a thousand years or more, though most of us know it from some version of this poem:

For Want of a Nail

For want of a nail the shoe was lost.

For want of a shoe the horse was lost.

For want of a horse the rider was lost.

For want of a rider the message was lost.

For want of a message the battle was lost.

For want of a battle the kingdom was lost.

And all for the want of a horseshoe nail.

As a kid I was impressed by the poem’s drama, the small ripple in the pond of fate spreading outward to become a tsunami on the shore. I understood the idea – causation rooted in carelessness – but the context didn’t mean that much to me. I didn’t ride horses, and even then I wasn’t much intrigued by the glorifying of knights and battles and the romanticizing of the internecine city-state warfare which eventually, through colonization, turned Europe and its far-flung settlements into destroyers of the world. (Not that I understood any of that then…)

As I stumbled through high school, college, and grad school and discovered through my own steady stream of mistakes the importance of attending to the details of life, whether putting oil and coolant in the car, starting an essay early (still working on that one!), or packing the right amount of food for a three-week canoe trip, my own context for nails and battles took shape.

Once I got to Antarctica and started working in astonishingly remote sites at the edge of the living world, I learned to pack extra nails and shoes and to think very, very deliberately about planning for the work that lay ahead. It doesn’t come naturally to me; I’m a lateral-thinking, loose-limbed guy who likes to wander. Eventually, though, I was running my own small field camps in East Antarctica and the Transantarctic Mountains. My love for the work and the place was balanced precariously atop a dread that I’d end up in the middle of nowhere and have forgotten to bring enough fuel or to pack the can opener.

Due to a carelessness toward the natural world we began avidly practicing two or three centuries ago, we’re losing all sorts of kingdoms now. The animal and plant kingdoms we call biodiversity are being decimated. The oceans on this ocean planet are suffering a rapid shift in temperature, acidity, and populations of species across the spectrum of marine life. Wetlands and rainforests that enrich the terrestrial world have largely disappeared. And even around the South Pole, a vast kingdom of ice no human had seen until 200 years ago and whose age makes the entire history of our species seem like dust in the wind, is quickly and inexorably changing because of us.

We’re at a stage in the Anthropocene now where each of us in the wealthiest, most resource-depleting nations plays an active role in undoing the ice of West Antarctica. My title for this week’s writing, “The Thwaites Glacier and You,” is meant not only for the sea level rise that will impact you but for our impact on the ice: “Every year,” writes David Wallace-Wells in his book The Uninhabitable Earth, “the average American emits enough carbon to melt ten thousand tons of ice in the Antarctic ice sheets.” Ten thousand tons is about 39,000 cubic feet of ice, the volume of a five thousand square foot house with eight foot ceilings. Every year, for each of us.

A story that conveys this cascade of impacts in stark terms is that of the Thwaites Glacier in West Antarctica, popularly known now as the “Doomsday Glacier.” It’s also a story of the complexity and fragility of Earth systems, even one as vast and seemingly stable as a continent covered in mile-deep ice. And it’s a story of incredible scientific effort, over years, to understand the subtle mechanisms that control a vast area of ice which will, in turn, impact the globe.

A few Antarctic basics first, though:

Antarctica is the size of the U.S. and Mexico combined, or China and India combined.

An ice sheet is a massive, sometimes continent-scale accumulation of ice; ice sheets were common at the height of the recent ice age, but now they exist only in Antarctica and Greenland. An ice cap is a very large region of stable ice at high elevation from which glaciers flow downhill. A glacier is river of ice, often hundreds or thousands of feet thick, flowing down through mountain valleys. An ice shelf forms when the flow of glacier ice extends out, floating, into the sea. Sea ice is not glacier ice; it forms when the surface of the ocean freezes.

The Antarctic ice sheet began forming 34 million years ago and reached its current extent about 14 million years ago.

The continent has three main regions: East Antarctica, West Antarctica, and the Antarctic Peninsula. In roughly logarithmic scale, East Antarctica holds 90% of the ice, West Antarctica 10%, and the Peninsula 1%.

There is enough ice in Antarctica, if melted, to raise the level of the world’s oceans nearly 200 feet. You can get some sense of that scale by flying for many hours over the undifferentiated mile-deep ice, but perhaps the most relevant way to perceive this is to stand at your local beach or shore – whether in Maine, Miami, or Malaysia – and imagine the water rising eighteen stories above you.

No one is worried about all of Antarctic ice melting in any human timeframe, if at all. It’s West Antarctica that is on the chopping block.

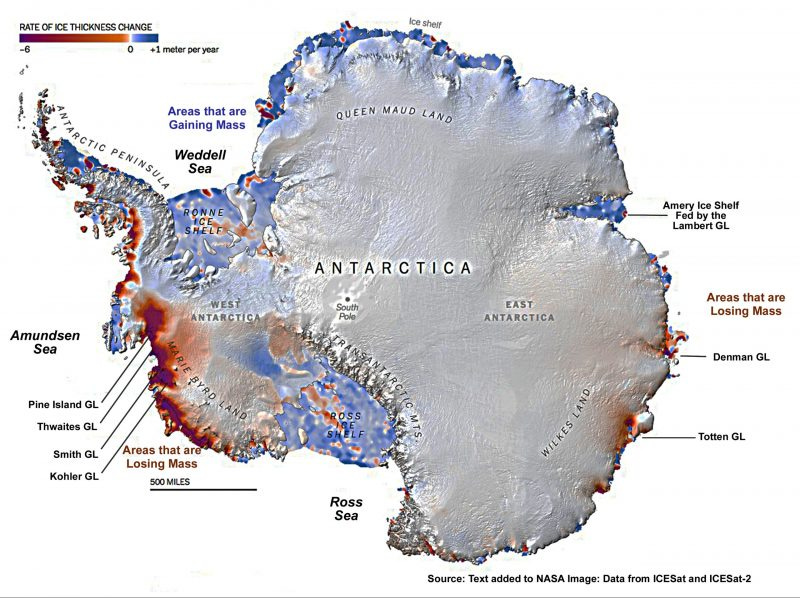

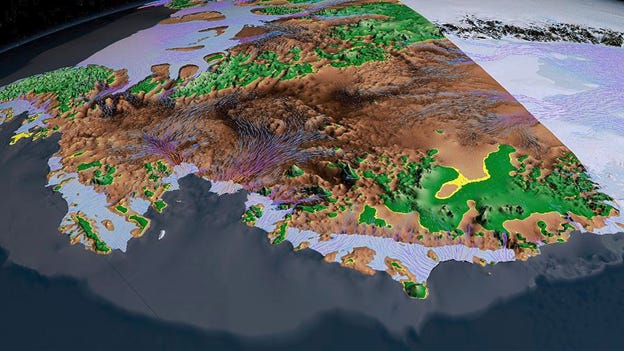

The difference in fate between West and East Antarctic ice sheets has to do with their foundations. The East Antarctic ice sheet lies almost entirely on a continent above sea level. The West Antarctic ice sheet, however, is the last marine ice sheet on Earth. That is, much of its foundation is below sea level and resting on the ocean floor. This makes it much more susceptible to fluctuations in climate and ocean conditions. Here’s a map of what things look like beneath the West Antarctic ice sheet:

The green areas are above sea level, yellow is sea level, and everything brown is below sea level. The purple lines represent glacial flow. In the center of the image are the purple flow lines of the Thwaites Glacier, one of the largest glaciers on Earth – the size of Florida, and 70 miles wide at its mouth – moving rapidly into the Amundsen Sea. Note the deep subglacial valleys feeding the Thwaites and, to the left, the Pine Island Glacier. Between them, they drain much of West Antarctica.

That’s not a problem unless, as is happening now, the rate of glacial flow outpaces the build-up of glacier ice from snowfall, and the resulting increase in sea level impacts the eight billion primates (many of whom live on the coast) who don’t want sea level to change. Antarctic ice is an Earth system that either accumulates ice, maintains a stable ice sheet, or loses ice. Fluctuation in that process, until now, has been entirely natural. Those eight billion primates, though, have tweaked the climate to the extent that ice loss in West Antarctica is rapidly accelerating.

It’s long been thought that meaningful changes in Earth’s ice sheets proceed at a glacial pace, over thousands or tens of thousands of years. But while that might be true for the center of East Antarctica, all indications now are that West Antarctica is a sensitive beast. The process by which this happens has everything to do with the capacity of the West’s ice to pour out through the valley now occupied by the Pine Island and Thwaites Glaciers. Here’s a helpful schematic that explains, in part, how that happens:

As the schematic explains in its numbered steps (1-7 in black, illustrated within the two glacier images by 1-7 in red), the process of glacial retreat in West Antarctica involves warm upwelling from a climate-altered Southern Ocean and an increased rate of ice loss. It is, of course, a complex process. Not unlike the nail-to-kingdom cascade illustrated in the poem, there is now a fairly well understood sequence of cause-and-effect that has led to this Anthropocene transformation of the WAIS. Keep an eye on the illustration above as I expand on it here:

In a warmed (and still warming) global climate, the ocean warms even faster because it acts as a heat sink for the atmosphere. As both air and water are warmed, wind patterns and ocean currents are altered. In this part of the Southern Ocean, the main culprit seems to be winds from the tropics, which are now more often pushing slightly warmer water under ice shelves on the edge of the Amundsen Sea. This warming increases the calving of icebergs from the leading edge of the ice shelves. The ice shelf retreats until it no longer acts as a brake on the flow of the glacier. Without an ice shelf slowing glacial flow into the sea, the Thwaites Glacier picks up speed. As it does so, it becomes thinner (less tall) because forward motion far outpaces the ability of snowfall to replenish the lost ice.

The only mechanism holding back very rapid glacial retreat is the grounding line, the area near the leading edge of the glacier where it touches the sea floor. Once the face of the Thwaites retreats behind the grounding line, the “Doomsday” stage of the process becomes clearer. All indications are that the Thwaites will continue collapsing up into the heart of the WAIS over a very short period of time (relative to normal glacial pace). The final step in this cascade, then, will be the subsequent collapse of glaciers which feed into the trough where the Thwaites once flowed.

Much of this has already happened, or begun. In recent years, the flow rate of both the Pine Island and Thwaites glaciers has accelerated even as they’ve thinned and retreated behind their original grounding lines.

Looking at the schematic here is a good reminder that there’s so much I could write about how we know what we know about the Thwaites and its fate. You can see here some of the ways in which data has been gathered – by satellites, ships, seismic studies, drill teams, drones, and lidar-equipped planes – but what you don’t see are the long cold summers of living in tents and dealing with equipment failures and harsh weather. The scientists who have dedicated their career to understanding and articulating the WAIS have done extraordinary work in one of the most remote, hard-to-access corners of Antarctica. Ships couldn’t reach deep into the Amundsen Sea until the 1990s, and still sometimes fail to reach the Thwaites area today. Veteran WAIS scientists, their grad students, and support staff have done incredibly difficult work over decades, slowly and persistently building up a case for one of the most transformative scientific discoveries of the Anthropocene.

There are about two feet of global sea level rise locked up in the Thwaites Glacier alone, and about eight more feet in the rest of the WAIS that seems destined to follow the Thwaites into the sea.

Finally, I should pause and note that the Thwaites story, and the WAIS story more broadly, is not a simple humans-screwed-up tale. The data describe a much more subtle situation. A 2017 discovery of dozens of volcanoes under the WAIS, for example, suggests that glacial flow might sometimes be lubricated by warmer meltwater. The WAIS, as I wrote earlier, is a sensitive beast which fluctuates much more easily than researchers once believed, sometimes moving even faster that the worrisome pace of recent years. But those fluctuations, caused by warmer or colder periods, balanced each other out. Until recently.

New research suggests a subtle set of changes over the last century. There seems to have been an anomalous but perhaps natural warm period in the early 1940s that destabilized the WAIS. The best guess at the moment is that our ongoing warming of the climate and oceans prevented the WAIS from stabilizing in the years afterward, beginning the process of rapid collapse we’re witnessing.

Given all this, it’s important to note that this story of a human-caused retreat of Thwaites is not really about the direct impact of our actions, like so many other Anthropocene stories (strip mining, overfishing, wetland destruction, etc.). Thwaites has retreated quickly in the nonhuman past. This story is about all the rippling unintended consequences of our impacts, however subtle.

For want of a clean fuel, the ice sheet was lost.

Next week I’ll talk about how and when the WAIS contribution to global sea level might play out, and draw a fuller portrait of the consequences for life on Earth, including us. While you’re waiting breathlessly for that… you can listen to an excellent podcast from The Conversation titled “Thwaites Glacier: the melting, Antarctic monster of sea level rise,” just out a couple weeks ago.

And you can dream of horses without shoes and runaway glaciers:

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

Two good news items from Anthropocene: New research into chemically recycling the most common plastic waste, and new analysis from researchers at Oxford makes it clear that rapidly switching to a green energy economy is a really good idea simply for the economics. Trillions of dollars are at stake, and the faster we eliminate fossil fuels the more money national economies will save.

From Mother Jones, more hard environmental news from the bizarrely right-tilted Supreme Court: the court seems poised to gut the Clean Water Act, specifically the EPA’s capacity to regulate intermittent, seasonal, or otherwise temporary waters, all of which are essential to protect biodiversity from development.

From Orion, stories of indigenous women in the western Amazon rising up to defend the land.

In related news from the Guardian, indigenous leaders are demanding that the world’s largest businesses and banks stop bankrolling the deforestation and destruction of the Amazon.

Want to see the climate-addled world from NASA’s perspective? Take a deep dive on their Climate Change page for data, analysis, and articles.

From BBC Future, a long, thoughtful, neutral history and analysis on the question of whether the world is overpopulated with humans.

Hello everyone: For anybody who noticed that I'd forgotten to fill in a factoid about the age of the Antarctic ice sheet - Thanks, Jim! - that has now been corrected in the online version of the writing. The ice sheet began to form 34 million years ago and reached its current extent about 14 million years ago.