The Thwaites Glacier and You, Part 3

10/20/22 – A fuller portrait of sea level rise and its impacts

Hello everyone:

The midterm elections are on November 8th. Regardless of your politics or opinion of politics, if protecting and restoring the natural world are important to you, be sure to vote for the candidates most likely to respond to the climate crisis and to fund the conservation of biodiverse land. To reshape the world we have to reshape policy.

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read some curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

When we decide to take a walk to “be in nature,” it’s us choosing to reconnect with the real world. This time of year, that choice might be a conscious decision to look for edible mushrooms, autumn leaves, or migrating warblers. It might be an unconscious need to breathe in the de-stressing benefits that park, forest, field, mountain, beach, or desert has to offer. It might be a need for some quiet joy. Either way, the walking is itself one of the few things we still do in our boxed-in lives that would still be familiar to our ancestors from the first 99% of human history.

In reconnecting, we break down the gap we feel between our bodies and the community of life. I think we all know, on some level, that the division has never been as deep as we believed. For one thing, the self is always embraced by the natural world, no matter how artificial our lives. We are vibrant animals on a vibrant planet. For another, underneath our couch-potato sweats or business attire is a vast galaxy of microbes that travels with us wherever we go. Whatever “I” am is a collection of species in and on my body. Still, we live abstracted lives in which food, shelter, and relationships often feel more synthetic than natural. We need to take that walk.

The relaxation or wonder we might feel on a good outing reminds us of the world beyond ourselves, and that we are woven into it. We feel the hard edges of our individuality dissolve a little. Our senses spark against the array of life around us. The eyes, especially, pull the real and vibrant world into our sense of self. The warblers call, and we respond.

There is an increasing price of reconnection in the Anthropocene, though. It is the grief that comes with understanding what’s been lost, what’s at risk, and how much must be done merely to stem the tide of losses. To reconnect is to recognize that it will take several (relatively enlightened) generations of our descendants to restore the community of life to some semblance of the world our species was gifted as we evolved. Anything less will not be enough.

Aldo Leopold, in A Sand County Almanac, said all of this in one sad and beautiful line: “One of the penalties of an ecological education is to live alone in a world of wounds.” And this was in 1945, when population was only 2.3 billion and we had just embarked on the “Great Acceleration” in human impacts. The world of wounds has grown inexorably since then, and the need for universal ecological education has never been greater.

The sea level rise that’s occurring, and the accelerating rise that’s coming, promises a new type of loss. In the scope of Earth history, a rising or retreating sea is normal: continents shift, sink, or rise, while ice sheets arise and retreat. But on a human timeframe and in a human-filled world, each new foot of sea level rise will be catastrophic for coastal life, including the hundreds of millions of people who reside there.

We have from our origin been a species drawn to the ocean for its bounty and for the access it provides to other lands. Culture after culture defined itself by its relation to the sea, as they still do today, from Greenland to Patagonia to Indonesia. In the Anthropocene, though, as a fossil-fueled technological economy spread across the globe, shipping and ports have become essential and fast-growing hubs of human endeavor. Those hubs now look extraordinarily vulnerable, with a predicted sea level rise of two to seven feet by 2100. The essential infrastructure of port communities, whether in villages, towns, cities, or megacities, will have to coexist with, or retreat from, the perpetual threat of inundation.

New Orleans, post-Katrina, has in recent years become the American poster child for a city threatened by the sea. It is that, of course, but it is also a symbol of the Anthropocene tradition of building coastal cities on shaky ground. New Orleans has sunk over the last 300 years as 30,000 acres of swamp were drained to become (temporarily) dry neighborhoods. Likewise, cities from Mumbai to Boston have been built on low-lying marsh or on filled-in gaps between islands. I think that for all of its narrative power in this moment, within a half-century the New Orleans story will have been lost in the flood of tales told of cities underwater, battling waves, or on the move. New Orleans may, like its story, be lost by then too.

Sea level rise isn’t only a matter of increased erosion, tidal flooding, destroyed lives and homes, insurance company bankruptcies, and mold-filled basements. Rising seas will require a complete reimagining of the urban environments that sustain much of the world’s population. Higher seas mean the disruption of whole industries and the jobs they sustain. Higher seas mean the intrusion of salt water into the lakes and reservoirs and aquifers that supply drinking water. Higher seas mean the relocation of homes and businesses, of essential transportation (roads, rails, bridges, subways, and parking), of sewage and wastewater systems, and of landfills and power plants.

Higher seas mean defending the poor and their low-lying neighborhoods as well as the wealthy and their property values. A future of higher seas mean that the politicians in cities and states and nations must efficiently plan far ahead and spend extraordinary sums merely to defend the potential for an ordinary life.

Imagine for a moment the effort and costs and heartbreak associated with moving or rebuilding or somehow defending Miami, Mumbai, Jakarta, New York, New Orleans, Lagos, Baltimore, Hong Kong, Guangzhou, Ningbo, or any of the other hundreds of coastal cities around the globe from four feet of sea level rise. (For example, it’s possible that Bangkok, Thailand’s capital and home to about ten million people, may need to be moved within the next few decades. It is currently sinking into the estuary on which it was built.) Then imagine how the impacts of defending or moving any one these cities will ripple inland like a tsunami, affecting far more people than the hundreds of millions who live in the flood zone.

For a view of four feet of additional ocean, check out When Rising Seas Hit Home: An Analysis by the Union of Concerned Scientists, a mapping tool that, among other things, allows you to see what U.S. coastal cities are facing under various sea level scenarios. (Click on the “Chronic Inundation Areas” tab and scroll down to select the “2100” option. The map shows Charleston, S.C., but you can zoom out to explore the coast.)

The good news is that the most recent research suggests that the moment we eliminate greenhouse gas emissions – that is, when we accomplish net zero emissions and atmospheric CO2 concentrations begin to fall – global warming would stop and global temperatures would remain where they are now for the next few centuries. (Note that I did not say temperatures would drop and return to the norm our species has enjoyed throughout its pre-Anthropocene history. We’ve warmed the oceans, and it will take many millennia for them to lose that heat.) If, on the other hand, we accomplish the lesser goal of merely stabilizing atmospheric CO2 concentrations, we would still have to cope with a bit more increase in atmospheric and ocean temperatures. In either case, we can expect sea level rise to be “moderate” rather than extreme, i.e. closer to three feet than seven by 2100.

The bad news is that with today’s policies and politics, neither of those scenarios seems likely anytime soon, which leaves us facing a growing cascade of consequences – impacts on every Earth system, transformation of the Arctic and Antarctic, species shifting and diminishing, human environments becoming less livable, etc. – for centuries. Delaying net zero and continuing on our current track will only intensify those consequences.

There is no avoiding at least some terrible sea level rise. It is, as they say, “baked into” the warming world we’ve made. This is the reality of thermal inertia in the Earth’s climate system, specifically the increased ocean heat and the lag time in response by the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets to a warming world. If we eliminate emissions tomorrow, ice will still melt, storms will still be intensified, oceans will still have expanded, and at least two and a half feet of sea level rise will lap at our doorsteps. We can – and must – limit the far, far worse sea level intrusion that will result from doing nothing about emissions, but we can’t avoid some of it. The ice that has melted will stay melted, and more – like that contained in the Thwaites – will melt.

I’ve hardly scratched the surface of the consequences of sea level rise on the human world, and haven’t addressed the best ways for us to become resilient to a rising sea, but I want to finish by digging into what isn’t talked about nearly as much: the consequences for the natural world.

To start, imagine the habitats – barrier islands, saltmarshes, tidal zones and flats, seagrass and oyster beds, shoals, mangroves, reefs, estuaries, beaches, dunes, and more – whose remnants are pinched between our coastal development (whether cities, farms, or villages) and the sea. Where do they go as the water rises? I’ve seen this described as “coastal squeeze.” In the worst-case scenario, they disappear (at a faster rate than they are now) as we abandon them in an attempt to fortify our infrastructure against the waves.

In the best-case scenario, they are deliberately and broadly expanded as green, biodiverse buffers against storm surge, and they are provided room to move inland with the water. It is common knowledge now among those planning for sea level rise that these habitats should be an essential part of how we reimagine our coastal lives. Call it coastal ecosystem restoration, “nature-based infrastructure,” or a lovely nexus of economy and empathy, but the more we do it the better. Sea level rise is, in some places, becoming a catalyst for restoration.

Coastal habitats are rich habitats. They are “ecotones,” i.e. mixing zones between habitats that are often more biodiverse than either one alone. Coastal ecosystems are fed on nutrients from both land and sea. They support an extensive array of species, many now threatened or endangered, ranging from migratory seabirds and songbirds to shellfish and salt-tolerant grasses. They cover only about 8% of the planet, but a disproportionate amount of biodiversity and productivity occur within them. As a recent call for papers by Frontiers in Marine Sciences put it, “As species richness and abundance tend to peak in these transitional areas, coastal ecotones are usually biodiversity hotspots and serve as local gene pools and biodiversity centers, deserving high conservation investment.”

So there is a tension between an Anthropocene need to restore the millions of lost acres of these ecosystems, particularly mangroves and marshes, and the Anthropocene future of rising seas. The solution, as I noted above, may be a win-win Anthropocene plan to help these natural systems thrive in the future flood zones.

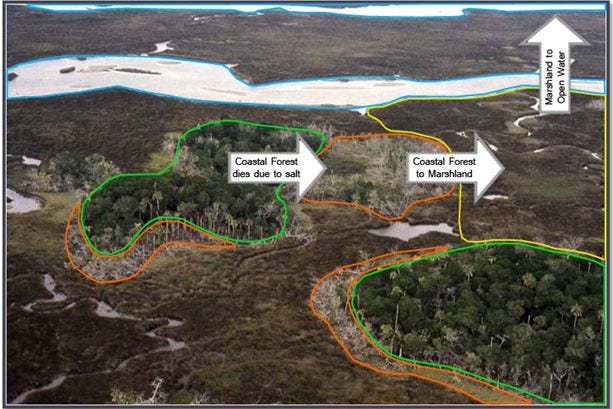

Yet how these coastal habitats are impacted is complicated. See the illustration above for a good example. There will be benefits amid the losses. Much depends on the type of habitat and how much room they have to move into newly-flooded shoreline. One study of six major estuaries along Florida's Gulf Coast found that with one meter of rise coastal forests and tidal flats will lose considerable area, while saltmarsh and mangrove habitats may substantially increase in size. Further south in Florida, though, at Ten Thousand Islands National Wildlife Refuge, salt water intrusion will diminish a freshwater marsh vital for various fish and migratory birds but will be good for the spread of mangroves, which support their own vital array of species.

Climate change or global warming is sometimes more appropriately described as climate chaos. The temperature trend is upward, certainly, but the impacts across climatic and biological systems are increasingly turbulent. Sea level rise is no exception. Millions of species around the globe are being, and will be, shifted or reduced or perhaps increased by rising waters. Simultaneously, the same species are coping with warming temperatures, increased ocean acidity, nutrient pollution and chemical contamination, invasive species, and more. There are layers of chaos, each with its own rising tide. All of this is happening on a incredibly fast timeline – a human one – rather than by slow evolutionary processes.

In the places where we lose these rare and invaluable coastal habitats, the ecological impacts will ripple inland too, as already fragmented and diminished natural populations decrease further still. Severe sea level rise will disrupt these ecological networks in the same way it will upend human economies, by breaking links in the chain and threads in the tapestry.

I started this series with the old folk poem built around the phrase “for want of a nail.” Perhaps a synonymous phrase is more relevant here: tipping point. The tipping points discussed in a climate-addled world are usually the big ones: methane release in the Arctic, say, or the disintegration of the West Antarctic ice sheet. But tipping points can be small too, like when a Louisiana barrier island erodes away and storm surge begins hammering a marsh or a neighborhood. Or when residents on the coast wake up to sea-flooded streets on a sunny day.

“Rising sea level is both subtle and blatant,” Annie Proulx has written, “we hardly notice it until a storm brings vast flooding.” That’s when we start to pay attention, and maybe even start advocating for restoring a protective (and species-rich) saltmarsh or mangrove forest between us and the sea. Tipping points, after all, can send ripples in both directions.

I’ll close by noting that while the Thwaites Glacier was named for an American glacial geologist, the word “thwaite” is an Old Norse term for an area of forest cleared for agriculture. For those of us who believe that the rupture of global ecology began several millennia ago when certain cultures turned to intensive tillage and pasturing, there is a small irony in the name.

We can imagine the cascade of events, with its tipping points, from “thwaite” to Thwaites: from concentrated agriculture came increasing population and urban societies; from technological growth came accelerating resource use; from the transition to objectifying and monetizing nature came the shift to a globalized fossil fuel energy economy and a warming climate, and now the predicted undoing of the West Antarctic ice sheet.

It’s something to think about when you take that walk. But remember to breathe deep and look for warblers too.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

From Anthropocene, a lovely success story of restoring habitat for amphibians in Switzerland.

From CarbonBrief, an article summarizing a new study on just how stark the inequity in greenhouse gas emissions still is: A mere 1% of the world’s population was responsible for a quarter of growth in emissions since 1990. That’s folks like us here in the U.S. One of the most powerful steps we can take to reduce our emissions footprint is to change where and how our money is invested. See the next news item below for details.

From Bill McKibben at The Crucial Years (his Substack newsletter), an eye-opening comparison of the ridiculously wasteful and pointless energy use of crypto currency with the much, much worse emissions from investments made by the big banks and investment firms. The top eight banks and top ten asset managers combined emit 79 times more carbon than crypto. Banking is, he say, “the dirtiest industry on earth, because Big Oil couldn’t survive without it.” Both industries must reverse these numbers if we’re going to any real progress. If you have investments, ensure they are not supporting the fossil-fuel industry. Here’s what you can do.

The Living Planet Index has been updated, and the news is not good. But the headline – populations have declined by an average of 69 percent since 1970 – is tricky, as this New York Times article nicely explains. I’ll write more about all this soon.

From the Global Footprint Network, a recent post on how in 2022 we’re still accelerating the excess use of the planet’s ecological resources. Overshoot Day – the point in the annual calendar when humans exceed ecological limits – this year fell on July 28th, the earliest day ever.

From the Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting, news that fertilizer run-off during the winter is now increasing. Ground that was commonly frozen is now less likely to freeze, and winter snow and rains are washing off fertilizer that was meant to be absorbed by plants in the spring. The result upstream is less efficient farming with increased investment in petroleum fertilizers, and the result downstream is more pollution, drinking water contamination, and toxic algal blooms.

Thank you, Kathleen. Leopold's quote is a powerful one. I'd like more people to hear it not so much to grieve the world of wounds but more to think about the value of that ecological education.

"One of the penalties of an ecological education is to live alone in a world of wounds." Oh! thank you for the quote, for your beautiful writing about how a walk in nature dissolves the increasingly think boundaries between ourselves and the natural world, and for all your writing which helps me feel less alone with the world of wounds that is so painful to wake to every day.