Hello everyone:

After last week’s ICE-heavy political diatribe, I thought I’d offer you something that sings a bit about my deeper relationship with ice. What follows is a lyric essay published 20 years ago in the 2005 Fall/Winter edition of the now defunct Isotope: A Journal of Literary Nature and Science Writing. I’ve cut some material and edited the rest.

A lyric essay, I should note, is a not-well-defined genre of prose that’s infused with some aspects of poetry, driven more by aesthetic connections than narrative. This essay, for example, does not tell a specific story, but there are narrative sections anchored by dates which connect with other fragments that address my topic, the experience of time in the seemingly timeless landscapes of Antarctica.

It’s an essay about both the aesthetics of a continent of ice and the cultural structures we’ve built to turn the metaphysical sense of time into the physical workday. I offer this to you as an Anthropocene essay because a) our outpost life in the Antarctic says much about our larger presence on Earth, and b) our ideas of time are as weird and colonial as our disruptive relationships with ecological space.

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read some curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

“On the question of time, science is bound to be solipsist. The problem of time is a problem of choice.” —John Berger, “Painting and Time,” in The Sense Of Sight

Nov. 7, 2000: I'm struggling with three dimensions, and lost in the fourth. A storm is buffeting the base. It's hard to see anything through the whiteout and blowing snow. Clarity and definition are eroded, white on white through white. Whether walking through the ground blizzard, or just staring out the window of my empty dormitory lounge, I see a world dusted and hammered with white. The snowy polluted shoreline, the snowy bulldozed hills: all of it stands pretty and flat-sketched against the empty Antarctic canvas.

On the edges of town, only the memorial crosses have weight, dark as ebony silhouettes against the erasure. During these "Condition 1" storms, we and our imported presence in the tabula rasa of the Antarctic are the only third dimension available. Try to go for a walk, however, and suddenly it's a struggle to believe even your existence here. We cast no shadow. We make no more than an off-white mark on a blank map.

McMurdo Station, Antarctica, is the geopolitical/scientific outpost the U.S. has struggled to maintain on the edge of the ice continent for 70 years. The largest base in Antarctica, McMurdo has had as many as three airfields and 100 buildings occupied by a summer population of over 1100 people. Most of us are not researchers of any sort: A majority of us manage operations and logistics so that a minority of scientists can trudge out into the elements to gather data. Yet we have inquiries of our own, the kinds of existential questions that arise when we place ourselves in an often liminal space.

We arrive again and again, years pass, but Antarctica feels as timeless as the Moon. Every storm feels like an attempted erasure. I've been taking notes on internal and external Antarctic weather since 1994, each year trying to find a story of time passing.

Walking out of the dorm, as I've done countless times for six summers now, I felt a strange calm swirl around me as I crossed the storm-laced open ground on my way to the galley. Time curled in on itself. I knew where I was, but had no idea when I was. I realized with pleasurable fear that, for a moment, I could not identify which summer I occupied. The memory of my time under Antarctic skies had sintered to the present. Time was subject to the whiteout.

As I walked out into the snow I walked into my notebooks. I had entered my written stratigraphy of summers in which old and new paths overlap. I have written my self, as well as this sense of geography that erases my self, into being. My few strange steps brought me within the realm of unpunctuated unknowing, the cloud of understanding that describes my time on ice.

Most of the Antarctic is empty space. The coasts are stony parentheses, containing only icy whiteness, an empty set. Just as if you took a microscope to examine the textures of a blank page, so the East Antarctic ice cap appears to the naked eye. Ruffled hardened snow stretches from your feet out across an area larger than China.

The experience of interior Antarctica is liminal, this strange stepping onto a frozen ocean, but there is little variety in that liminal space: a walk through any temperate landscape provides any number of imagined and scientific thresholds. Here we reside on the aesthetic and biological margins of life on Earth, but there are few borders within it.

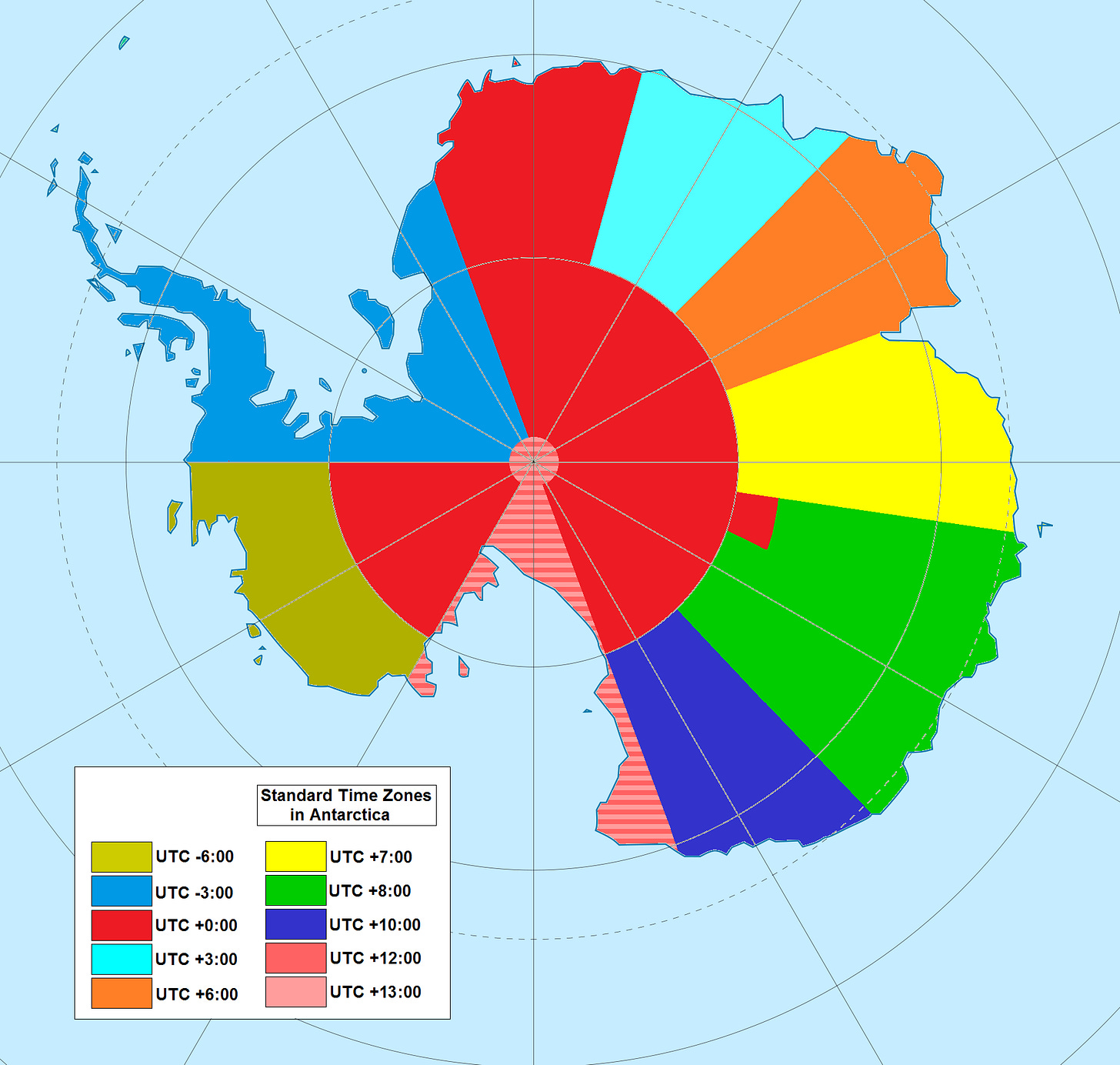

The shards of time zones around the South Pole notwithstanding, time finds few handholds here. Timelessness surrounds us in a landscape defined by a continuum of unframed moments. In the interior, I feel no story, no beginning or end.

This irrational experience of Antarctic time is the "native" experience, and the rational notions of mind and space which drive science have little to say about it, cannot recommend or obviate it.

We're so tied to our work schedules that we quickly outgrow the novelty of a summer day that is many months long. We punch the clock each workday while the sun rides the south polar thermal above and around the horizon. The two phases of the year that do resemble the temperate day/night cycle are ephemeral, twilight aberrations in the midst of the passage between light and dark. Despite the uniformity in our light, however, Antarctic bases keep a wild variety of times. Many set their clocks to match the port from which they deploy, while some are set to their home country. Some match their time zone, while many do not.

While stations that are neighbors communicate often, most have no occasion to chat across the continent. On those occasions, however, we reference Zulu time (Greenwich Mean Time) as a standard. Zulu is 12 hours behind McMurdo time, which is New Zealand time. The South Pole base, because it is American, is on New Zealand time as well, though it has each of the world's time zones at its doorstep.

The Italians deploy through Christchurch and are thus also on New Zealand time. Vostok Station, like each of the widely-scattered Russian bases, is on St. Petersburg time. Dumont d'Urville, the largest French base, is on Australian Eastern Standard Time because like the Australians crew and cargo arrive by ship every year from Tasmania. The Australian bases of Casey, Davis, and Mawson, strangely enough, are respectively 3, 4, and 5 hours behind A.E.S.T.

If I want to call my family in Maine, I have to keep in mind that I'm anywhere from 16 to 18 hours ahead, depending on daylight savings time in both places. Actually, I tend to think of them as six to eight hours ahead yesterday.

Daylight savings in Antarctica: We follow it, to stay in synch with the Kiwis, but otherwise it's about as useful a behavior as South Pole setting out a rain gauge. Out in the field camps, "local" (McMurdo) time is what we use with each other and for flight operations. But weather observations are passed back to the weather office in McMurdo as Zulu time, and planned radio comms are set up either on local or Zulu. Both of these are described via military time, i.e. on the 24-hour clock. So, for example, I might have comms with MacOps at 1330 local, but give a weather ob to MacWeather half an hour later at 01 Zulu.

Back in town, or at Pole, we have dayshift and nightshift, equally strange concepts whether it's summer or winter. But they have their effect: Separation from the rest of the community, and the slightly different cant of light on the ground during summer "nightshift," give me the sense that indeed one cold empty day could be made distinct from another.

Dec. 2, 2001: Abandoning our snowmobiles where the glacier ends its 300 foot thick flooding of Trudge Valley in the Allan Hills, Julian and I took off to explore a little bit of our backyard Mars. Our two-person camp was several miles behind us on the edge of the Odell Glacier. We'd driven upstream to see what this part of the hills could offer. We were in the middle of a three-month job building and maintaining a runway on the lower Odell. The Allan Hills are a set of barren ridges and valleys nearly drowned by the ice of the East Antarctic ice cap as it pours between the peaks of the Transantarctic Mountains. Walking these rust-colored valleys, we’re kin to the Mars rovers, roaming and photographing with frequent stops to pick up stones.

Down on the valley floor, we were surprised to see two battered orange Scott tents pitched at the foot of the glacier. We thought the nearest humans were in the Dry Valleys somewhere, 60 crevassed miles away. The two geologists from New Zealand's Scott Base were surprised to have two Yanks smiling and helloing them from outside their tents. Unfortunately, we woke them from a sleep schedule opposite our own: in order to find gaps in the helicopter schedule for their flight support, they'd shifted their morning to midnight. We stood around and talked like neighbors for a few minutes before Julian and I continued up the valley, leaving them to settle back into slumber.

Though we're out here alone together for a few months, Julian and I just met in October. We shook hands in McMurdo and starting packing for the trip. Over the last several weeks, I've come to admire especially his attitude toward the Antarctic. He fell in love with it years ago, like me, but has been very careful to come back only occasionally. Julian will work a summer on the coast, then take a few years off; then another summer in the interior, followed by more years off. “I like to leave when the party's good,” he says. I think it's also about keeping a poetic affair from turning prosaic.

We stopped again a mile farther, because Julian stumbled across a piece of petrified wood lying in the dolomite and sandstone gravel. Then I spotted one. Then another. Over the next few minutes we realized that the entire valley floor was littered with thousands of fragments of 220 million year old Glossopteris forest. Even much of the gravel was splintered fossil.

A now-extinct seed fern with tongue-shaped leaves, Glossopteris grew to a height of 12 feet. The dense fine-grained stone is the color of a November cloud, with every other growth ring mineralized black. Many of the fragments were also ventifacts. That is, they had been polished over millennia by wind-driven sand. They ranged in size from clumps like unabridged dictionaries to chips like Scrabble tiles.

Turning this history over in my hands was, to me, like hearing voices in a river. Here millennia flowed by while Antarctic time stood still and yawned. Only the stars look at this wood as if it were fresh grass. For me, standing here in the anteroom of the ice age, living a lifespan similar to the tree that became this stone, mortality and eternity seem like opposite sides of the same faceless coin. On an island of stone in a sea of ice, on a continent of no-life surrounded by the sea of plenty, lay these pale memories once fed by rain. The continent these trees inhabited is the same one whose dead land Julian and I are walking, but when they grew the ice was a distant mirror and the equator a closer neighbor. The passage of geologic time has been made palpable by this wood, as if each stone were a stem cell of time.

Most fossils are found in places where new forms have replaced them. Like us, for example. But nothing in Antarctica says to the mind "This is a tree," or "This is a good place for a tree." It's not even a good place for us.

Two hours later, on our way back to the glacier, swinging wide across a small sandstone mesa to see what we could see, Julian and I came across whole sections of Glossopteris trunks emerging from solid rock. Mostly they were at angles to the surface, but one or two were near vertical, looking for all the world like a stump from a Triassic cutting.

Then I found the most intriguing stone I have ever seen. About the size of a mittened fist, it was yet another gray and black striped piece of petrified wood, but it had been carved by the wind into an object of remarkable beauty and polished abstraction. It lay exposed on bedrock, where wind is able to carve its sculptures in the round, eroding stones at an estimated rate (for dolomite) of about .1 to .3 cm per 1000 years. Small grooves like the spacing between harp strings had been channeled into it by winds howling down from the ice cap. These grooves ran at right angles to the growth rings that swirled in their own elegant pattern under the smooth surfaces of the stone.

This stone is a plaything of time, or vice versa: organismic time has merged with geologic time, and together they are here at the mercy of glaciologic time, and under the thumb of the time it will take wind to grind this fossil into dust.

The loose stitches time takes to unite our warm bodies are unraveled by this cold. And yet, somehow, the substance of cold is the substance of time.

Dec. 4, 2001: Antarctica is the best source on Earth to find the bits of space punctuation we call meteorites, and the blue icefields inland from the Allan Hills are one of the best-known areas for such finds. The Mars meteorite that NASA claimed showed signs of life was found there.

These icefields mark where the East Antarctic ice sheet is locally dammed up by the Transantarctic Mountains. The ice is forced upward as it flows toward the mountains, and then steadily ablated by dry katabatic winds. Katabatics are gravity-driven cold masses of air that fall with fury from the ice caps down to the coast, sometimes for weeks at a time. All meteorites that have dropped from the heavens into the ice over millennia are swept up in the ice, then left high and dry on the blue surface of the ablation zones. Since 1976, the Antarctic Search for Meteorites (ANSMET) teams have found over 23,000 stones, pebbles, and specks waiting for them.

The Odell is a blue ice glacier well downstream of the famous icefields, a narrow 7-mile-wide thread tucked between peaks. It's not a likely place to find meteorites, because of the complications of such a journey. I'm still not sure how mine arrived.

Julian and I had moments earlier finished drilling the final hole for our runway markers. Three weeks of construction were complete, and we could finally set the oil-spewing auger aside. One of the things we hoped to do in our spare time was look for meteorites. Two ANSMET guides had flown out to our camp a week before, to look over the airfield. They couldn't stand the thought of a plane running over a meteorite.

I had pressed Johnny and Jamie, the ANSMET guys, for precise descriptions of the meteorite types, not least because the katabatics like to hurl small shiny bits of similar-looking dolomite from the Allan Hills onto the Odell.

Johnny, a quiet, grizzled man who has been guiding the meteorite teams since 1981, gave me a simple answer. "Just look for stones out of context." Otherwise, we'll go crazy picking up everything. "Where you see a rock by itself, or a larger one among pebbles, go check them out. The wind-blown rocks will all be the same size. Then look for the fusion crust." A fusion crust is the melted surface of the rock that once hurtled through our atmosphere before plunging into the cold bath of the ice cap. In a cartoon that kept playing through my mind, I imagined finding one that was still sizzling.

So as Julian and I happily turned our snowmobiles away from the drilling work, ready to eat lunch back at our camp, some three miles away, I swerved over to a too-large suspect. I'd picked up too many rocks already to be excited, but this one was big. It looked like a softball hit out of the park about a million years ago. But it wasn't dark enough, I thought, and had no smooth crust. Sure it was dolomite, I finally reached down with my filthy oily glove and turned it over, only to find a perfect dark chocolate fusion crust. I gasped like a schoolgirl and dropped the beast back onto the ice.

My find, at about 5.2 kg (11 ½ pounds), was one of the larger of the few hundred meteorites found this year. (Normally an ANSMET team will find six or seven hundred in a summer, but they lost a precious week pinned down by winds of up to 60 knots. Instead of gathering meteorites, they were losing tents.) Two weathered fragments lay nearby, which fit nicely onto the side I had first seen. It was an ordinary chondritic meteorite, the most common type. But it was big, it was heavy, and by the craziest luck in the world, it had sizzled into my life.

My hands, the first hands to have touched this object of deep time, had no idea how to tell my mind what they held. Or perhaps the reverse is true: my hands said "stone", while my mind said "asteroid". How long did it take to travel from outside our atmosphere to the innards of the ice cap? Seconds, I suppose. How long has it been waiting here on the ice? No one will ever know. How long was this fragment moving through space before it was snagged by our planetary net? About 4.55 billion years, the same age as the Earth.

4.55 billion years: I feel like I should play God with this thing, setting it gently back into space with a dressing of organic chemicals (is 2-cycle oil good enough?), and expect it to sprout life in some distant eon.

Here's something that looks at the petrified Glossopteris pieces as if they were grass, I thought. In the course of a few Earth days, my hands held both dinosaur food and firecracker fragments from the Big Bang. I was luck itself.

Dec. 18, 1994: A small berg broke off the McMurdo Ice Shelf a few years ago, but still waits for release from the sea ice just meters from its source. To reach it, a flagged trail guides walkers several miles out from McMurdo. Because the sea ice rarely breaks out to the edge of the shelf, the berg may be hunkered down for several years. So it sits like a lost dog, neither glacier nor ocean, neither origin nor destination.

Chewing through my McMurdo leash, I walked out on my own on a nearly overcast Sunday, our only day off. "Safety in numbers" is an Antarctic mantra, and no one is supposed to walk alone outside of town or the roads. But privacy is a rarity in town, and living here means several months of living on someone else's schedule. So I headed out for an impromptu date with this quiet behemoth.

Where did this ice begin? Which is to say, when did it begin? What impossible stories might be told about the journey of a piece of ice from its inland home to this coastal end? Astray from the monolithic ice shelf, it is now a colony of crystals irrelevant to the great flood that brought it here, and instead a small part of the charismatic diaspora of Antarctic icebergs. The berg is a chapter in a history perhaps too rich for data, a balkanization of ice and time.

I walked alone in a slow circle around it. It took perhaps ten minutes to do so, undulating up and down with the snowdrifts, stopping at points to see how a few summers of sunshine have sculpted the walls. A curtain of slow drips ceased as the sky clouded over. I felt like a fly buzzing in the ear of a ruined blue titan.

New Year's Eve, McMurdo: Celebrating the passage of time on a continent that resembles a ventifacted clock face. And what is time-telling if not a foundation of data gathering? Our inventions of calendar and clock led eventually to the machine-age which now powers our comfy existence in this reductionist Antarctic space. "Most of time and space is like Antarctica," writes Sara Wheeler, but not here, not tonight. We have sintered time and space to ego. It's time to dance.

Time is a type of weather, a form of weather, a weather. Patterns exist amid a universe of tendencies. Some of the tendencies form around our mental habits, and some are storms that consume us.

On the ice, fierce weather and time may fuse into a few violent, meditative brushstrokes: an experience, I have found, of accidental transcendence.

But Antarctic time is most often composed of days without measure, the summer a single day made identical by the sun revolving like a bulb without shade around the blue wall of sky. And the distance from our feet to the unreachable horizons owes nothing and gives nothing to time. This vast glacier of sky drowns in integrated silence the ticking of our little movements.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

From David Wallace-Wells at the Times, “You Are Contaminated,” the first in a series of articles about the ubiquitous poisoning of the world (and our bodies) by the industries we’ve empowered to do so. I highly recommend this piece for the big-picture view he takes of this fundamental Anthropocene phenomenon. His writing is often excellent: “Humans are porous beings, in ways more fluid than fortress.” Here’s his intro:

Everywhere they look, they find particles of pollution, like infinite spores in an endless contagion field. Scientists call that field the exposome: the sum of external exposures encountered by each of us over a lifetime, which portion and shape our fate alongside genes and behavior. Humans are permeable creatures, and we navigate the world like cleaner fish, filtering the waste of civilization partly by absorbing it.

From The American Scholar, “Sticking With It,” a well-written review of Mariah Blake’s new book, They Poisoned the World: Life and Death in the Age of Forever Chemicals, a comprehensive history of the the PFAS plague that now haunts the entire world, and the entire foreseeable future.

From SpaceWeather.com, some news about “The Great Starlink Reentry Event,” in which more than 500 Starlink satellites were brought out of orbit and sent burning through the atmosphere between December 2024 and July 2025. On one hand, this was now-routine de-orbiting of early-model satellites being replaced by newer versions. On the other, this was an astonishing and underreported event that, if initial research is any indication, is symbolic of what’s likely to be a dramatic, dangerous, and unplanned experiment in atmospheric chemistry. The thousands of new satellites being thrown up into orbit by SpaceX and its competitors are not merely changing reality in low-Earth orbit; they are, as they burn up after their short lives, filling the stratosphere with massive amounts of aluminum oxide, an ozone-destroying, atmosphere-warming chemical. And it’s going to get a lot worse:

With multiple companies racing to deploy megaconstellations, projections suggest more than 60,000 satellites could be in orbit by 2040. That means reentry debris could soon rival the natural influx of meteoroids, but with very different chemistry. Meteors are mostly rock. Satellites are mostly metal.

A simulation by NOAA scientists suggests that aluminum-rich space dust could heat the stratosphere and mesosphere by up to 1.5°C, and slow the southern polar vortex, potentially altering global weather patterns.

What happens next? We’re about to find out.

From Vox, a fascinating discovery of chemosynthetic life (rather than photosynthetic) abundant at great depths (more than 31,000 ft/ 9450 m) in ocean trenches. This suggests that much more of the supposedly “lifeless” deep ocean floor may be filled with endemic wildlife than we realize, and that plans for seafloor mining are even more harmful than have been claimed.

Also from Vox, an important story about the landscape-scale problem of bullfrogs in the American west. Like all invasive species conflicts, this one is complex, and like many such stories it seems unfixable. Bullfrogs are native to the U.S. east, but out west for the last century or more they’ve moved into our altered wetland landscapes and bred prolifically, feeding on and displacing many less-aggressive native species.

From Grist, an update on what to expect from the meetings in Geneva to try and finally establish a meaningful global plastic pollution treaty.

From Yale e360, “Shrinking Cod: How Humans Are Impacting the Evolution of Species,” an account of how intense fishing pressure for the largest cod in the Baltic Sea in recent decades has selected for slow-growing, smaller fish. The genes for the larger cod that were common just four decades ago now scarcely exists in the species. Human behavior is forcing rapid evolution across the globe, from insects to fish to birds and elephants, and those changes are rippling outward through the rapidly changing natural world.

Amazingly beautiful writing. I was swept away by it, transported by it and coming out to the other part of this writing, the section of cites as interesting and useful as they always are, was like regretfully returning to a narrower and dryer land. Time is the central mystery for me.

Philosophers say that time is intimate to change: one cannot arise without the other. But what is not spoken of is the great land itself, the desert places either of sand or ice, and how they hold time, change, and our imagination in their numinous hands. They actually are life-giving, those places and the longer we are away from them the more quickly we age.

“The shards of time zones around the South Pole notwithstanding, time finds few handholds here. Timelessness surrounds us in a landscape defined by a continuum of unframed moments. In the interior, I feel no story, no beginning or end.”

Although I have many favorite quotes, this one takes the top spot. The entire piece is beautifully written, Jason.

Although when I read the first paragraph, I wished this was an audio that I could listen to while I walked the steep hills of the NEK, keeping an eye out for the next shady spot, whether it is from a tree canopy or telephone pole (I am thin enough to walk in it’s shadow, if I walk kind of side ways). No doubt even your words could cool me, but the thought of snow and whiteout storms and glaciers a world away, was helpful . It is steamy hot and the air is still stifled by smoke particles from Canada.