Hello everyone:

In this time of exhaustive (and exhausting) attacks on democratic norms and environmental protections here in the U.S., it’s tempting to try to offer you a weekly round-up of 1) what’s been lost, 2) what, for now, is still standing, and 3) what good activism is doing to push back.

As much as I’m paying attention, though, I’ve decided for now not to force you to drink too much from that hydrant. I’ll link to useful articles in the curated Anthropocene news below, but otherwise I’d rather keep my focus on portraits - both large-scale and more intimate - of the modern human relationship with life on Earth. Politics is a vital part of that picture, but it’s not the whole picture.

This is for my own sanity, in part, and it’s also because you already have access to an extraordinary amount of reporting on the executive branch’s shitstorm, the legislative branch’s myopic complicity, and the judicial branch’s slow and so far insufficient response. I’m pretty sure that you’re already paying attention. I’ll offer my thoughts on the problems and solutions when I know that I have something to add to the discussion.

But if you are looking for that kind of round-up on the environmental side of the Trump 2.0 chaos, I want to introduce you to a writer you may not be familiar with yet:

and her Owl in America series at . Rebecca’s tagline for the Owl in America series is “Notes from an American environmentalist,” and she describes is as “a series of letters chronicling the Trump years from the perspective of an environmental lawyer.” If that reminds you of ’s , that’s because Rebecca’s work was inspired by Richardson.If this interests you, take a look at the latest Owl in America post, in which Rebecca does an extraordinary job of putting together a legal, ethical, and philosophical framework for assessing what we’re all experiencing in this difficult moment.

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read some curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

We all need healthy reminders of what actually governs our reality outside the fictions, distortions, and tempests of our political life. As Anirban Mahapatra wrote in

about the consequences of the Trump administration’s all-out attack on science,This matters because the real world doesn't bend to ideology. Gravity is not a belief. Atoms are not feelings. The movement of the planets is not liberal or conservative. Natural selection is not an electoral college. Climate change is not a swing-state voter.

And this week I’m here to play with the phenomena which perhaps best represent the mysterious and wondrous working of the real world beyond our bizarre and maladapted civilization: clouds.

I have a deep and cheerful relationship with clouds. Or I did, anyway. I spent much of my young adulthood devoted to them as aesthetic marvels, flexible metaphors, and reminders of the transience of existence. My too-serious trail name on the Appalachian Trail was Cloudfinder. On that walk, and later, as I wandered a few thousand miles by foot and canoe, I was always conscious of moving through the space between the solid architecture of the land and the mutable forms of clouds.

In my late twenties, I put together an entire manuscript of small strange poems rooted in the act of cloud-watching. And when I arrived in Antarctica and immediately fell in love with it, it was in part because I had found an entire continent that seemed as wild and unknowable as a cloud.

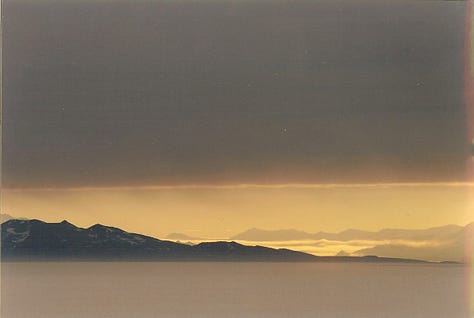

It was 1994. I’d arrived on the ice in late August, a time of strange skies hovering between the total darkness of winter and the constant light of summer. The sun did not rise and set, really, but undulated along the horizon. That sidelong polar view of the sun provided several hours of dusk and dawn each day, the August halflight casting a thousand shades of crepuscular color across the sea ice of McMurdo Sound and the glacier-filled Transantarctic Mountains.

Colors of aquarium merged with the colors of fire. A subtle shifting radiance of orange, raspberry, chrome, lilac and more drifted over what in the glare of summer was composed only of bruised variations of white. The air and ice seemed lit from within, light emanating from the landscape rather than merely reflecting from it. I had found a luster to the ice that my life on Earth did not predict.

But the wildest light source in our indigo twilight came from nacreous clouds. Named for mother-of-pearl (nacre), nacreous clouds are intensely iridescent and silky. The hues are muted neon, like oil-on-water but brilliantly backlit, an otherworldly beauty in an otherworldly place. Perched 10 to 15 miles (16-24 km) high in the stratosphere, at temperatures around -120F (-85C), they catch and refract sunlight shining from several degrees below the horizon.

Nacreous clouds are one of two types of polar stratospheric cloud (PSC). Both are common only in the polar regions, particularly Antarctica. While all clouds are mysterious, we know even less about PSCs. As with so much in this era of human impacts, though, what little we know tells us that our changes to the Earth are larger and stranger than we thought.

The non-nacreous type, known as Type I, are only slightly iridescent but make up for their plainness by being a chemical cautionary tale. They contain hydrated droplets of nitric acid and sulfuric acid, which act as a catalyst for an atmospheric chemistry that depletes the ozone layer. And, unsurprisingly, it seems that the supervolcanic level of greenhouse gas molecules being pumped out by Anthropocene culture are increasing these Type I clouds.

Worse, as we increase the presence of PSCs we may be intensifying warming in the polar regions. Research suggests that 50 million years ago in the early Eocene, when the planet was largely ice-free and alligators roamed the warm waters of northern Canada, PSCs may have been far more common. Climate models seem to have overlooked the importance of PSCs, and this oversight may partially explain why these models continue to underestimate the astonishing speed of today’s warming in the Arctic and Antarctic.

I’m reminded of recent news about the rapidly increasing swarm of Starlink satellites (among others) now falling from the grace of orbit with intentional regularity. As each short-lived device tumbles Earthward - now about 4 or 5 per day - they burn up and leave a fire-and-smoke chemical trail of aluminum and other substances uncommon in the stratosphere. This, it turns out, is an unplanned and unmanaged planetary experiment that will take decades (at minimum) to play out. Like PSCs, aluminum oxides act as a catalyst for ozone depletion, and the tons of accumulating aluminum particles may eventually change how much sunlight the atmosphere reflects back into space.

We are busily making clouds that are not clouds.

Perhaps the first rule of cloud-watching is this: Extraordinary beauty and extraordinary transformation are all around us, and they are inseparable. Above us, every day, an endless array of forms appear and disappear. In the Anthropocene, though, we’ve redefined what transformation means, even in places as wild and unknowable as a cloud.

Is it a cloud?

If it’s a cloud it will move on.

The true shape of this thought,

migrant, waning.

- Charles SimicI wrote in “Reimagining Rain” that as a young man

I had a great fondness for sprawling on mountaintops and watching a scattering of flat-bottomed summer clouds dangling rain as they sailed at eye level across the forests and waters of this beautiful world.

That was an image of clouds in the distance. There is similar magic in living blind on a mountaintop while renting space within a cloud, watching the hushed passage of vapor so dense that it passes visibly through one’s fingers. That was me on an alpine peak here in Maine decades ago, as I lay sprawled on stones mottled with damp lichens who had been fed by clouds for time immemorial.

The lichens and I traveled briefly but cheerfully together through the nebula, expecting nothing and finding it, right where it’s always been, all around us. Later, as I stumbled my way down the mountain trail and back into the clarity of day amid the solid architecture of the forest, I felt like I’d left a womb. In this maternal sense, each cloud is an incubator of possibility, a carrier of seeds.

But just as mothers now transfer microplastics in utero, the raindrops and ice crystals that form clouds are often nucleated on the unbreakable chemistry of plastics and PFAS-laced dust that sail into every corner of the planet. Rainwater everywhere is unsafe for long-term unfiltered use.

Let me say that again: For the first time in human history, and for no good reason, it is no longer safe to drink unfiltered rain anywhere on Earth.

Contaminated clouds are still clouds, but they are darker clouds, and they are here to stay. The Anthropocene is an era not merely of an altered world but of an altered future. Clouds, humans, and the rest of life are traveling through a new nebula. The map of what is possible has changed, as have the seeds we carry.

The Planetary Boundaries framework assesses nine essential limits on our behavior if we want to maintain a healthy Earth. (I encourage all of you to become familiar with the concept.) Of the six categories we’ve badly violated already, Novel Entities may be the least familiar. The others describe, more or less, how we’re changing the atmosphere, bulldozing the continents, overheating and depleting the oceans, decimating plant and animal populations, and changing Earth’s chemistry. Novel Entities is a cheerful-sounding name for the malevolent fog of new industrial chemicals we’ve spread on a massive scale but with little foresight: synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, herbicides; thousands of types of plastics that act as endocrine disruptors and worse; anthropogenic radioactive substances; and many, many more.

As I wrote above, we are busy making clouds that are not clouds, but these industrial chemical inventions for human/corporate purposes are, from a planetary perspective, better described as interventions in natural processes. We think we’re as magical as clouds, and more solid than fog, but we neither understand clouds nor live up to the elegance with which they help sustain the community of life.

We can be better cloudmakers, though. First and foremost, we need to bring forests back. Reforesting the continents - not merely planting trees, but allowing complex plant and animal communities to rebuild - brings back moisture, clouds, and rain, because forests are rainmakers. They regulate climate on small and large scales by regulating the flow of water between soil, plants, and sky. They release natural terpenes into the atmosphere to help clouds form and send the water back to Earth.

As

explains in “Seeing Forests Through the Clouds,” much of the recent unexplained acceleration in Earth’s warming may be due to increased burning of our remaining forests, and to the subsequent reduction in the heavy low cloud cover that helps cool the planet. Clouds are still unpredictable wildcards in climate models, but we do know at least that they represent the healthy functioning of life.Another rule of cloud-watching, then, is that clouds are as grounded in the Earth as we are. They stitch earth and sea to sky. And like us, they are no longer innocent. We both carry a disruptive chemistry wherever we go, and we are both deeply involved in the warming that is rebirthing the world.

And if I could answer back,

if once I had a cloudier tongue,

what would I say?

- Charles Wright

Here’s another view of a cloud from the inside. I was canoeing alone to a family cabin, crossing a pond late one summer night through a very dense fog. There was a full moon, bright but unseen overhead. It was like traveling through a lit glass of milk, with only a tight halo of calm but glittering water around my boat. I’d crossed the pond many times before, day and night, but never like this.

I could have safely hugged the shore, but wanted to be surprised. I left the beach in the right direction and paddled quietly into the bright darkness. I had no reference to judge speed, angle, or distance. Remarkably, somewhere out in the middle of the pond a strange small beacon-to-nowhere appeared from ahead and to the left, zigzagging its bright self across the middle of the pond and across the bow of my boat before disappearing, still lit, to my right. It was too fast, too big, and remained lit for too long to be a firefly, I was certain, but then again I was certain of nothing. I sat still in the mist for a while, then paddled slowly but contentedly in the wrong direction.

That’s what it means to be in a cloud. The industry jargon that tells us daily that our data and digital lives are “in the cloud” bothers me (as you might expect from someone who once adopted the name Cloudfinder). “The cloud” is a perverse and flimsy children’s story, but it’s as sticky as myth because it’s convenient. It distances us from the “staggering ecological impacts” of data centers, as an MIT Press Reader article described it.

Ralph Waldo Emerson has an answer for this, if we borrow his concise indictment of meat-eaters: “You have just dined, and however scrupulously the slaughterhouse is concealed in the graceful distance of miles, there is complicity.” I seem to have traded in my canoe for this computer in recent years, joining more fully in the impacts even as I write about them.

Both clouds and “the cloud” exist in the real world and have immense consequences for life. Only one, however, is both necessary for our continued existence and elegantly unpredictable in its movements. The other, a euphemistically-named technological parasite on energy and water resources, provides space for an often unnecessary trove of civilizational muttering, memory, and memes. (I’ll file this essay under “muttering.”)

There’s a notebook entry highlighted in the MIT article that illustrates this:

2021. At Chuparosa Park, I hear it, too. Above the cries of children playing, dogs barking, cars racing by, it soars. My ears prick up with the music of the Cloud, a discordant symphony of text messages, emails, cat videos, and fake news, pulsing, thrumming in my ears. Just past the basketball courts, the picnic tables, and the prickly pears, the source is visible for all to see: a CyrusOne data center.

Every time I think about the lunacy of data centers, especially amid the rush to develop and incorporate AIs into every aspect of modern life, I think about the rule I’d like to apply to every major industry: Each planned product should be at least as demonstrably beneficial to public welfare and ecological well-being as it is to its corporate owner. If not, it must earn an exemption or be redesigned.

Finally, then, a third rule of cloud-watching: It’s not enough to acknowledge the mysterious workings of the real world, and the extraordinary beauty of all that surrounds and nurtures us. We have to work to protect that mystery too. We have to enter the cloud and navigate by heart. We must prioritize the clouds that contain and nurture our real lives.

“...he makes this secret little love fixed upon the cloud of unknowing his principal concern...” - Anonymous, The Cloud of Unknowing

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

Again, from Rebecca Wisent and Fearless Green, take a deep breath and read her long-form assessment of what’s happening in the new U.S. administration, and subscribe to see how she puts that assessment to use in reporting on the future of American environmentalism.

And take a look at the Project 2025 Tracker, which is a fascinating, concise, and useful tool for measuring, agency by agency, the clearly enumerated goals of the Christian nationalist, anti-science, fascist/authoritarian playbook against what has already been accomplished. Unsurprisingly, if this were a scoreboard, the Project 2025 folks would be far ahead of the competition (which is us).

From Emergence, a wonderful interview with Zoe Schlanger, author of The Light Eaters, a book that beautifully explores a new array of research on the intelligence of plants. It’s a book that we all need to read. Here’s a sample from the book to get you started:

Every bundle of muscle in my body was woven from the sugars plants spun from moisture and air. My blood cells that course through my veins like water through rootlets are each kept ruby red with the oxygen plants made…. Every inward breath of mine was first breathed out by plants. In this material sense, in terms of what they’ve contributed to my physical being, they are as much my relatives as any family member I know.

From Undark, a review of a new fascinating book that explores how other animal species think about death. Here’s a useful excerpt:

Charles Darwin once described his masterwork “On the Origin of Species” as “one long argument” for the role of natural selection in evolution. While Monsó does not mention Darwin, her book’s structure does seem to echo the kind of step-by-step argumentation found in “Origin.” Chapter by chapter, the author lays out the case for animals having some conception of death, gradually honing in on exactly what that conception is, and how it may vary from species to species.

From Vox, another powerful piece from Benji Jones, this one on the ubiquity of microplastics and PFAS chemicals in rain. He notes that we once had a terrible problem with acid rain, but we’ve largely solved that through good legislation that restricted companies ability to cause that harm. But now what haunts our rain and snow in every corner of the planet is far worse for human and environmental health.

From Nautilus, a survey of the damage rocket launches can do to the natural world around launch sites.

From the Atlantic, a look at the clumsy and half-witted destruction wrought by this administration on U.S. Antarctic climate science. I’m particularly fond of this closing paragraph:

Trump will almost certainly bequeath a warmer Earth to the next administration. The past five American presidents have each done the same. What makes Trump different is his insistence on disrupting the basic apparatus of climate science, the effort to understand how warm the planet will one day become, and how quickly its seas will rise. Heating up the world for future generations is a crime, but this is a cover-up.

Jason, I have such immense gratitude for the poetic fervour with which you document and describe the astonishing beauty of the natural world and the alarming consequences of modernity’s steady encroachment on everything natural. As we go through living in these times where most people seem deeply oblivious to the extent of ecological harm & destruction, voices like yours are so precious and necessary. You remind us that no matter how terrifying it gets, there is still always beauty to be found. Thank you.

Hey Jason! I’m new to Substack and just came across your profile (thank you, mysterious algorithm), and I’m already enchanted! Your writing has this poetic touch that somehow makes even a heavy topic like planetary boundaries feel almost soothing to read, haha. I’m Brazilian, and last year, a study revealed how deforestation in the Amazon is drying up the "flying rivers", those invisible streams of moisture that travel through the air, creating clouds thousands of kilometers away. It’s almost magical. Yet, as the rains diminish, it’s not just the forests that suffer. It’s the hydroelectric dams, the crops in dry regions, and ironically, the very agribusiness that often turns a blind eye to the environment. It’s strange, really, how we sometimes disconnect from the bigger picture, what a brilliant Brazilian quilombola writer once called “cosmophobia.” We end up unraveling the threads that hold everything together, even the ones tied to our own survival. Anyway, thank you for your words. You’ve got a new reader here!