Hello everyone:

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read some curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

Pressed to the Ground

We are a sight-driven species, but we hear the future before we see it. Our eyes find walls and mirrors while our ears catch hints and echoes on the wind. We hear over the horizon and around the corner, forming images with the mind’s eye long before the shape of what’s to come arrives.

I love the metaphor for empathy embodied in the English language idiom, “I’m all ears.” It’s absurd and kind all at once. It is interactive, attentive, and more intimate than social. Tell me your story, it says, I’m right here. Perhaps because it speaks of intimacy and connection, “I’m all ears” is common across many languages.

There are darker stories of ears, however. In one of the most powerful poems of the last century, “The Colonel,” Carolyn Forché salvages a scrap of (bitter) hope from an image of human ears fallen to the floor of a cruel El Salvadoran military officer’s house. In the late 1970s, she was in the country as a human rights activist, documenting the horrors of that nation’s destruction by a terrorizing, paranoid regime.

The poem is a masterclass in building tension and scene, but the punch in the punchline is far more extraordinary. Here’s the last half of “The Colonel”:

...The parrot said hello on the terrace. The colonel told it to shut up, and pushed himself from the table. My friend said to me with his eyes: say nothing. The colonel returned with a sack used to bring groceries home. He spilled many human ears on the table. They were like dried peach halves. There is no other way to say this. He took one of them in his hands, shook it in our faces, dropped it into a water glass. It came alive there. I am tired of fooling around he said. As for the rights of anyone, tell your people they can go fuck them- selves. He swept the ears to the floor with his arm and held the last of his wine in the air. Something for your poetry, no? he said. Some of the ears on the floor caught this scrap of his voice. Some of the ears on the floor were pressed to the ground.

Forché suffered for decades from what she heard and saw, finally writing her memoir What You Have Heard is True in 2019. Her difficulty was not only the trauma of bearing witness, however. The U.S. government wouldn’t admit the monstrosity of the El Salvadoran regime it supported, labeling her as delusional to the media and the public who had read her poems. And some of the literary world thought she had transgressed the bounds of the art form by wallowing in the muck of politics.

Forché was all ears in El Salvador, listening to everyone, and it nearly killed her. Her work was, and is, inspiring. So often - nearly always, in fact - we refuse to listen to the hard, dark news of the world, whether political or ecological. The destruction is right in front of us, like an fox’s corpse in the road, and we steer around it. Here’s what Forche’s El Salvadoran guide and mentor told her (as reported in the Times review of her memoir) about the task she faced when returning to the comfort and safety of the U.S.:

“I promise you that it is going to be difficult to get Americans to believe what is happening here,” Gómez tells Forché. “For one thing, this is outside the realm of their imaginations. For another, it isn’t in their interests to believe you. For a third, it is possible that we are not human beings to them.”

From the comfort of home, other people’s (or species’) suffering seems optional. Our denial is universal, cross-cultural, and even natural, but it’s impossible in this moment not to think of the poor souls stolen from their legal existence here in the U.S. to the horror-filled prison run by another El Salvadoran dictator. And, more to the point, it’s impossible not to think of the entire Republican party refusing to listen to, or see, what’s directly in front of them, which is the full, unbridled destruction of the political, social, and ethical principles they have sworn to uphold.

This kind of deafness erodes society, often fatally. Don’t tell me your story, it says, I’m not listening.

Wrong Forever

There are things we hear once and know that they’re wrong forever. Some are crimes against the innocent, some are unnecessary deception, some are brutality at scale, and some are all of these at once, and more.

We are all unfortunate enough to live in a moment, this moment, in which that list of things we wish we’d never heard grows longer - and by edict - every day. But these fast and furious additions are neither different nor new. Cruelty and selfishness are the point, yes, but cruelty and selfishness are the ancient shadows of the kindness and compassion that also bind us together. All can occupy hearth and home, but our darker tendencies thrive more easily at the altitude of the pedestals upon which we place those in power.

For my purposes here at the Field Guide, I am thinking mostly of crimes against the natural world. As Pope Francis wrote, “the earth herself, burdened and laid waste, is among the most abandoned and maltreated of our poor.” If asked what broad environmental cruelty troubled us the most, we might sensibly point to the continued unnecessary use of planet-heating fossil fuels, to the toxic but profitable sales of single-use plastics and PFAS chemistry, or to the heartbreaking carelessness with which our purposeless civilization is pushing thousands of much more dignified, beautiful, and fully evolved species toward extinction.

And I am haunted by all of those. Lately, though, I’ve been thinking at a smaller and more symbolic scale, about a crime that has long rankled me. It’s one that might not even be on your list: ethanol.

Ethanol production in the U.S. is, in a word, infuriating. Imagine a worst-case scenario in which government devotes tens of billions of dollars in subsidies to major agribusiness corporations for an unnecessary fuel that a) drives up the cost of food globally, b) erases an area of lush and biodiverse habitats the size of New York State, c) puts good farmland to poor use, d) wastes huge amounts of water, e) vastly increases pesticide and herbicide use and their harms to soil, waterways, and the ocean, f) worsens climate change, g) damages engines, and h) does all of it for short-term, small-scale political gain. That’s ethanol.

If there were a level in Dante’s circles of hell for those committing acts of pure harmful stupidity against the natural world, it might be an endless field of corn through which the afflicted wandered without food, water, or shelter.

When the great writer Craig Childs did just that - wandering and suffering for days through an Iowa cornfield in a July heatwave with the heat index around 120° F – for a chapter of his terrific book, Apocalyptic Planet, he found an Anthropocene emptiness less hospitable to life than the deserts he explored for other chapters. In the genetic black hole of a chemical-soaked monoculture, insects were rare and the earth seemed dead. “This was not the soil that farmers were pinching a century ago, nothing like it,” he writes. “This was now a created substance, an anthropogenic substrate.”

I could rant about ethanol for a while, but I’ll offer you a few essential points instead:

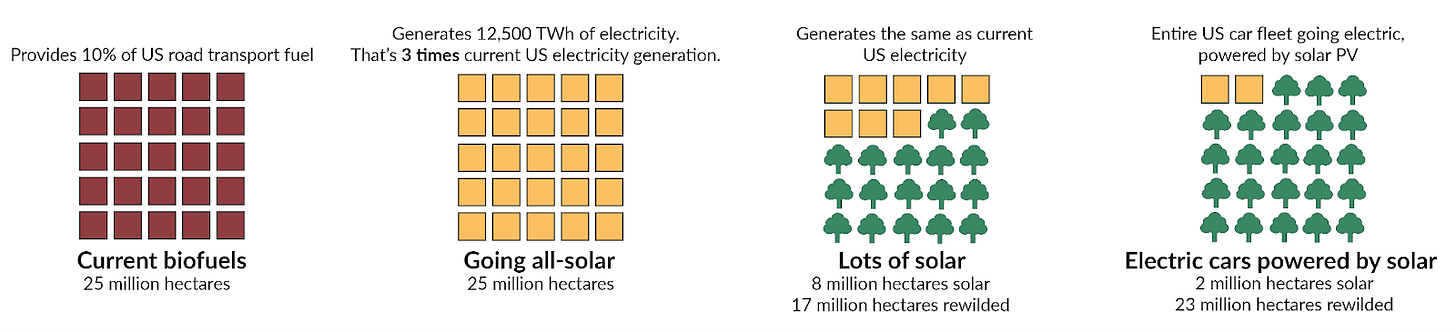

The inefficiency of ethanol is staggering. An excellent new Anthropocene article explains that if a mere 3.2% of the 12 million hectares (~30 million acres) of land sacrificed for corn ethanol were converted to solar farms instead, it would produce the same amount of power as the entire ethanol crop, while more than tripling the amount of solar in the U.S. grid. (All while providing agrivoltaic space beneath the panels for certain crops, grazing sheep, or pollinator meadows.) Converting 46% of corn ethanol land to solar would, by itself, meet the U.S. decarbonization goal for 2050. Turning all of that land to solar would power the entire U.S. grid three times over.

As a Times op-ed noted, ethanol and other biofuels are “like a return to the horse-and-buggy era, when farmers had to grow millions of acres of oats and hay for transportation fuel, except now the crops are processed through ethanol plants instead of animals.”

While broadly claimed to reduce carbon emissions, ethanol actually increases emissions, once we account for fertilizer use and “land use change,” a euphemism for converting carbon-sequestering natural ecosystems to a monoculture meant to burn.

Nearly half (44%) of corn grown in the U.S. is grown for ethanol. (Another 44% is grown for animal feed. Only the remaining 12% is sold for human consumption.) As

at Sustainability by Numbers elegantly phrased it, “Putting food into cars is a poor use of land.” Here she offers some more rational and ecological alternatives:

“Destroying rainforest for economic gain,” E.O. Wilson once wrote, “is like burning a Renaissance painting to cook a meal.” The same is true for grasslands, wetlands, temperate forests, and any other lush ecosystem bulldozed into cruel simplicity. When I say “ecosystem,” I mean an incredible community of plants, animals, and microbes woven together by a galactic number of ecological connections. I mean the fox and bison, the tall prairie grasses, the mycorrhizal fungi. I mean the land that breathes rain back and forth between cloud and aquifer. I mean the susurrus of the wind through cottonwoods and cedar, and the ear-tickling sounds of tens of millions of migratory birds sailing at night across a land that cares for them, and listens to them.

Because We Forgot to Listen

You’re not alone when you don’t like what you hear in a world taking the wrong path. You’re not alone when you notice the absence of life that should be singing. You’re not alone when you hear what you cannot believe is true - those things that are wrong forever but allowed to continue as if they were right and good - and want to protest amid the silence of the crowd.

We are not alone in seeing the burnt but still-beautiful world for what it is, we're not outliers or crazy, we're not alone in bearing witness to the roadkill, the dead zones, the billions of cat- and window-killed birds at our feet, and landscape-level loss of innocence everywhere. And we’re not alone in bearing responsibility too.

The truth of the Anthropocene is the truth of our ordinary lives: What we do is who we are. What we practice, as I told my students, is who we become. The good news is that a change in practice initiates a change in ourselves and, miraculously, in the world around us. The Anthropocene is defined in part by the one-to-one relationship between human behavior and planetary health.

The artificial world we've been making (from the real world we're unmaking) is the world we’ve been building within us. As within, so without. The endless and useless corn fields are also inside us. Just as building a house requires permits from one social authority or another, so our repurposing of the lush, green, endless Earth into flat, hot, dead-end industrial sites requires our permission too.

It's not simple cause-and-effect, I realize. We are each born into a world built by those who profit from the destruction and who advertise that profit as if it were ours as well. We are each born into the Anthropocene, with every generation more distant from what the nurturing, astonishing Earth has been for nearly all of our species's history. Life does not sing like it once did, largely because we forgot to listen.

And so we are, as I try to say here often enough, both trapped and complicit. The world is stripped of its green benevolence by our collective presence, whether or not we're driving the bulldozer. But we can listen for the bulldozer beyond the horizon, and we can listen for it within ourselves too. We can (collectively, at scale) change our behavior, and in so doing change the world. It may take centuries, millennia, or millions of years for the planet to regain its primeval fullness in the wake of the mass extinction we seem set on inflicting, but the sooner we take the right path the sooner we heal.

Those who listen have heard the future coming for some time. Now many more hear it too, because they can see it: The first of its burdens have already arrived. Our ears, once pressed to the ground, now travel the transformed world gathering stories for policy and poems.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

From Atmos, a thoughtful review of an exciting new book, Is a River Alive?, by one our finest living writers, Robert Macfarlane. Macfarlane explores with his usual depth and intensity the question behind the rights-of-nature movement: How do we determine whether the great flowing rivers of the world are merely powerful or endowed with a presence that requires recognition?

From

at Chasing Nature, a lovely tribute to the magic of warblers in the peak of spring migration. But like most tributes to wildlife these days, the essay is an ode to their decline too. “To be sure, springtime is a season of joy,” Bryan writes, “and now as well a reminder of profound loss.”From Aeon, a thoughtful but unpersuasive article on the civilizational challenge of rapidly declining birthrates and the likely massive reduction of the human population in the next century. The author is rational, unlike many of the pronatalists that I wrote about recently. His argument is largely economic, per usual, but he also emphasizes some assumptions about the cultural implications of having fewer and fewer young people to shape society and economies.

From ProPublica, a cautionary tale about two generally liberal U.S. states, Oregon and Washington, which have failed miserably at keeping promises to increase large-scale sources of renewable energy, largely because they have ignored a central permitting issue.

From JAMA Network Open, another cautionary tale about the increased prevalence of Parkinson disease in people living near golf courses. The study identifies correlation, not causation, but intense pesticide use (especially in the U.S.) is a likely factor.

From Reasons to be Cheerful, a good-news story of a new and very popular activity in the Netherlands: ripping up sidewalks to plant flowers, shrubs, and trees. The government is encouraging and supporting residents of Dutch cities to turn portions of sidewalks into green spaces that help absorb and control run-off from rain.

From Anthropocene, the surprisingly large carbon benefit of telemedicine.

Another great upbeat weekly news round-up from

and The Weekly Anthropocene, which posts stories from around the world highlighting the clean energy transition, rewilding, conservation, and much more.

Jason, isn't it passing strange that we have been brought to speaking of this industrious wasteland? We carry the PFAS and ethanol, methane and carbon in our cradle as surely as blanket and nook. They are our blanket and nook. We leave the cradle carrying them. We write in the language of the cradle and we teach blanket and nook and so we have fashioned our world. But we, the cradle and its contents, are transforming as does our world. We become stranger every year, less intelligent, less intelligible to each other and preceding generations. Our numbers are mutating us to something strange and terrible, something quite comfortable in the wasteland of its diminished world. It is incomprehensible this future, glorious and dark. I fear the future.

Good lord, that information about ethanol is infuriating. Of all the ways we’ve enshitified the world that has to be one of the stupidest! Though it’s becoming almost impossible to rank all the stupidity going on around us.

Honestly I have never felt more like a stranger in a very strange and hopeless land…

*sigh*