Hello everyone:

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read some curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

I had planned to write this week about Antarctic ice, a topic that feels very much like an old friend. Specifically, I thought it was about time I explained the so-called “Doomsday glacier” in West Antarctica known to scientists as the Thwaites Glacier. The media nickname is a nod to the glacier’s oft-reported rapid retreat and the likelihood of its subsequent release of much of the West Antarctic ice sheet along with it. There is about ten feet of global sea level rise currently locked up in that ice sheet. It’s a story worth telling, and knowing, but it will have to wait. (It’s okay. We have some time.)

I have been distracted by eels.

Hakai, an environmental magazine focused on coastal stories, produces some excellent reporting, including a recent take on the grand mystery of eels, a natural history story that has fascinated me for years.

Why is this an Anthropocene story? Because, as the great Wendell Berry said, “To cherish what remains of the Earth and to foster its renewal is our only legitimate hope of survival.” So I like to tell a natural history story once in a while to remind myself, and you, of what remains and what’s worth fighting for.

We’re in a migration season now. The air has cooled, but the occasional monarch butterfly still passes through our garden here in coastal Maine. A pair of yellow-shafted flickers probed the yard a few days ago for grubs and ants to fuel their flight south. As strong winds flogged New England recently – the outer bands of Fiona as she ran headlong toward Atlantic Canada – my brother reported watching a steady stream of hawks sailing through the gusts far overhead as they began their movement down the eastern seaboard.

And so it goes, the vast seasonal movement of life all around us, some of it seen and much of it unseen, particularly from our boxed-in lives. Reading about migration is heartening in a way that is also overwhelming. Life swarms across every dimension of this planet in a profusion that should make us blush, not merely for the complex beauty of its movement but because these migrations, unlike our noxious traffic, enrich the world rather than deplete it.

There are the epic migrations of Arctic terns (a 4-oz seabird traveling 55,000 miles per year) and sooty shearwaters (only slightly less), bobolinks (songbirds shifting 12,500 miles a year between South American and North American grasslands) and bar-headed geese (traveling over the Himalaya at oxygen-deprived altitudes up to 23,000 feet), hummingbirds and humpback whales, caribou and tuna, wildebeests and walruses, swallows and salmon, and so many more. There are very particular migrations like the great majority of eared grebes who converge from around North America to feed only in Great Salt Lake and Mono Lake each year, and there are the hard-to-imagine multigenerational migrations of monarch butterflies and common green darner dragonflies. And there are the incredible, if less directional, peregrinations of albatross and swifts, feeding and sleeping aloft for months at a time, as if flying were not an effort but a state of being.

Migrations are made possible by physical and sensory adaptions beyond human capacity, whether navigating by smell, starlight, solar and lunar positioning, infrared light, or sensitivity to Earth’s magnetic fields.

All of these migrations speak of a planet knitted together by evolution over millions of lush, blue-green years, in which species experiment with long-distance survival strategies until extraordinary solutions emerge, like Arctic terns living 30-year lives in which they travel the equivalent of three round trips to the Moon as they shift between polar regions, or like three generations of green darner dragonflies completing a migratory cycle around North America.

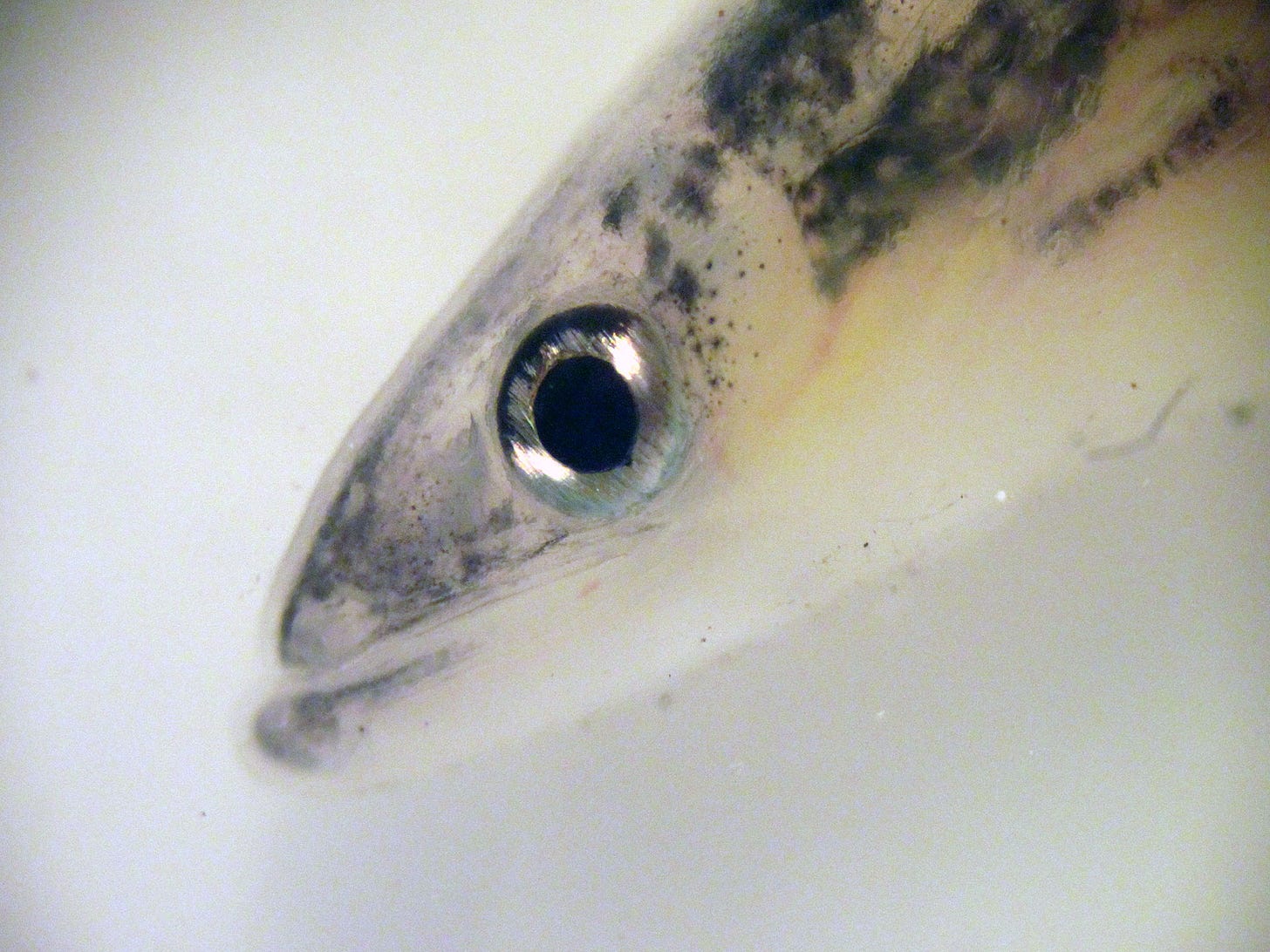

And then there’s the eel. Of the roughly 800 fish species we call eels, I’m writing here about the 15 species of Anguillidae eels, and mostly about American and European eels, but they are all fascinating. Freshwater eels migrate in and out of the waters of 150 countries. They are sacred to the Māori of Aotearoa/New Zealand, who “have over 100 names for eels describing their different colours and sizes, and they are revered as a link to the gods.” Other eel species inhabit inland freshwaters of Australia, Indonesia, East Asia, and islands of the South Pacific; here is a remarkable story of a researcher living among eels in the highlands of Tahiti.

Wherever they exist eels are beautiful, powerful, and strange, adding their own layers of wonder to the wonder of migrations. Migratory eels can breathe through their skin, allowing them to travel overland in moist areas. They can swim backward as well as forward. Eel gender seems determined by their ultimate location, with the majority of eels who migrate to the upper reaches of a watershed becoming female and most of those who remain downstream in estuaries or brackish water becoming males. Females end up two to three times larger than their future mates. Eel gender was the focus of centuries of frustrated research in Europe, where no one (including Sigmund Freud, who dissected hundreds of them before retreating into psychology) could find the reproductive organs. One of eels’ complexities is that those organs only develop at the end of their life as they prepare for the migration back to their spawning grounds.

Unlike salmon, river herring, sturgeon, and other fish whose anadromous life cycle takes them out to sea to mature and then back to freshwater to spawn, eels are catadromous. They spawn in the ocean but live the bulk of their lives in estuaries, streams, rivers, ponds, and lakes. If you have marveled at the ability of salmon to find their way home to the same small stream where they first hatched, eels should boggle your mind. Theirs is one of the largest unseen migrations on Earth, and perhaps the most mysterious.

All migratory eels are born into mystery, and they return to that mystery to die. Well, we all are, but here I mean specifically that each eel species, whether in Tahiti or Japan or Europe, has a particular spawning area in the deep ocean that has largely remained beyond scientific inquiry. For the Japanese eel (which exists throughout East Asia), it’s the West Mariana Ridge in the western Pacific Ocean. For the New Zealand longfin eel, it’s deep waters somewhere off Tonga. For South African eels, it’s an area north of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean.

Wherever eels spawn, we’ve never witnessed it. Only the Japanese, who consume 70% of the global eel catch, have gotten close. Through patient, methodical, and expensive ship-borne research they’ve tracked tagged eels swimming to an area of seamounts on the West Mariana Ridge and pulled up fertilized eggs in their trawls. More intriguingly, they’ve discovered that the eels spawn only at a depth of 150 to 200 meters and only for the last few days before a new moon.

Though often loners throughout their freshwater adulthood, eels end their lives in mysterious trysts in secret ocean locations by the waning light of the moon. The more we study eels, the more romantic they seem… But it gets better. While no one has witnessed eels mating in the wild, genetic evidence suggests that great masses – thousands to hundreds of thousands – of eels will gather in a great writhing orgy to reproduce via panmixia (species-wide random mating). And then they die, their bodies sinking to the seafloor even as their young rise as fertilized eggs to the surface to begin the life cycle anew.

The best guess, based on finding tiny eel larvae, is that European and American eels’ journeys begin and end in the Sargasso Sea, an area in the North Atlantic that encompasses Bermuda and extends a thousand miles to the east. It is not a sea but a gyre bounded by currents and full of its characteristic seaweed called sargassum. Breeding areas in the Sargasso for the two species are thought to overlap but remain distinct, with American eels beginning their drift northward before the European eels.

If this is their reproductive home, then their astonishing migratory story goes something like this: After the panmictic orgy, in which each female releases 10 to 20 million eggs, the adults die and the fertilized eggs hatch into flat, leaf-shaped larvae called leptocephali which, drifting northward for months on the Gulf Stream, morph into tiny transparent fish called glass eels when they reach the continental shelf. Some European young will travel over 6,000 miles over two years before reaching their coastline. A few days after entering coastal waters, the glass eels darken and become known as elvers. Each elver finds its home somewhere in the estuaries, streams, and lakes, and spends its life there as a yellow eel, slowly increasing in size. Females may grow to be four feet long. Yellow eels are capable of breeding after just several years, but some remain for decades. Little is known about how or why eels vary in their breeding behavior, other than that eels grow more slowly in cold waters. One European eel was found to be 85 years old.

The population of American eels stretches from coastal Venezuela and Central America in the south to Greenland in the north. European eels range from Morocco and the Azores eastward through the Mediterranean to the Middle East and northward to Iceland and Scandinavia. As both species’ final life stage approaches – the epic swim back to the Sargasso – the eels undergo a remarkable set of physical changes. They become deepwater ocean fish, essentially. They develop the countershading of ocean fish – dark above and brighter below. Their eyes grow several times larger and more sensitive to blue light, their skin thickens and their fins grow larger, and their swim bladder strengthens in expectation of fighting tough ocean currents. Their digestive system dissolves because traveling to the breeding site is more important than eating. In this stage, as their color brightens, they are known as silver eels.

This migration seems to happen at depth as the eels navigate with a sensitivity to magnetic fields and a capacity to follow thermal and salinity differences in deep ocean currents. Like salmon, they’re migrating back to the place of their birth, but it’s fascinating that the breeding ground is defined not by a narrow stream but by temperature, salinity, lunar positioning, and who knows what else in the midst of the open ocean.

But it’s the young eel migration that boggles. It’s beautiful and strange that these tiny, transparent young travel the rough and wild Gulf Stream for many months, navigating (according to an excellent comprehensive hypothesis) by “(i) lunar and magnetic cues in pelagic water; (ii) chemical and magnetic cues in coastal areas; and (iii) odours, salinity, water current and magnetic cues in estuaries.” Smell plays a vital function; the tiny leptocephali are already as sensitive to odors as adult salmon. And the Moon is particularly important, as evidence suggests the young may navigate by the electrical signal given off by a new moon. Furthermore, young eels may imprint on their chosen river’s specific electromagnetic signature “to form a lifelong, rudimentary map to navigate back to the Sargasso Sea as adults.” The glass eels seem to have a remarkably complex set of navigation tools which they use differently at different stages of the journey.

The question that lingers for me, finally, is how the young distribute themselves throughout the species’ range. What makes a glass eel aim for Haiti or the Mississippi River or Maine? France vs. Finland? No one is certain how the tiny transparent young eels navigate to the specific estuaries, rivers, and lakes they’ll call home. Put another way, how do the young decide to exit the Sargasso and Gulf Stream and choose which North American or European inlet to migrate into, given that unlike salmon they have no sense memory of the location, and given that their “parents” mingling in the Sargasso will have come from different regions? If it were random distribution determined by the currents, it seems to me that the results could be wildly different year by year.

I hadn’t found any description of this until I read Alessandro Cresci’s comprehensive hypothesis article quoted above. Perhaps the most interesting idea out there, while still neither confirmed nor complete, is that glass eels may be drawn to pheromones released by the existing eel population in the estuary or river. In other words, this part of their navigation is not done by map but by beacon. Laboratory studies have shown that migratory glass eels are strongly attracted to eel-scented waters. But how far out to sea can this beacon can be detected? Are the glass eels being drawn from a distance to choose one home over another, or are they merely sensing at close range that there is a safe home for eels ahead?

When I asked Cresci about this, he called it the “million-dollar question” and said the likely answer is a combination of factors:

Large-scale ocean circulation, timing of spawning and hatching, and spawning location definitely play a key role in where larvae will end up. Larval movement behavior is also likely to play a key role. However, how leptocephali swim and orient in pelagic waters is totally unknown.. and it’s one of the biggest missing pieces of the puzzle.

And so the mystery lives on for now.

Speaking of safe homes for eels, this wouldn’t be an Anthropocene story if I didn’t detail some of the threats posed by our current civilization to eels and their beautiful lives. The list is long but unsurprising: overharvesting, dams, habitat loss, climate change, pollution. Overharvesting has decimated European eels especially. There’s a very high value placed on glass eels, which are sold to Asia to be farm-raised for the domestic market. Some protections are in place but illegal harvesters provide 90 tons of eels to Asian markets every year. One fisheries manager calls it “by volume, the largest wildlife crime of animals on the planet.” Only 10% of the European eel population remains, and is listed as critically endangered by the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature).

The American eel, in slightly less dire straits, is listed as endangered. In the U.S., only Maine and South Carolina have legal glass eel fisheries. Here in Maine, as elsewhere, fisheries managers have struggled to keep a lid on the harvest of glass eels since the prices paid by Asian markets went through the roof. In 2022, Maine elver fishermen harvested over 9,000 pounds of glass eels with a value of $19.5 million in a matter of weeks. Stories of single-night catches earning tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars are not uncommon, nor are stories of buyers with trucks full of cash. Unsurprisingly, a gold-rush mentality leads to smuggling, theft, and other nonsense.

Dams are brutal eel-killing structures. Not only have they completely blocked passage to ancient eel habitats for generations now, but in those places where eels can get around them and spend years maturing upstream, it only takes a moment for hydroelectric turbines to make mincemeat out of most of the eels heading home to the Sargasso. Other habitat loss results from coastal development and severe pollution in waterways. And then there’s climate change, which with its general disruption of fundamental ocean dynamics (temperature, acidity, stratification, currents, biodiversity, etc.), should pose numerous threats to the eels in the decades to come. For now, though, no major changes to their essential, mysterious meeting place in the Sargasso Sea are known.

Thinking about eels and their fate, I’m reminded of a line by the Peruvian poet/fisherman Freddy Guardia in the short documentary, The Ceviche Fisherman: “Nothing stays the way you want it to. That’s why we have memories.” Lest this seem too somber a note to finish on, though, I’ll quote Wendell Berry again: “To cherish what remains of the Earth and to foster its renewal is our only legitimate hope of survival.” So, with the enduring mystery of eels in mind, let’s do that.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other (ocean) Anthropocene news:

From Mongabay, a very-bad-news update on the likelihood of deep sea mining for polymetallic nodules. For background on this terrible idea, read my essay on the topic, “Still Digging,” from last September.

Also from Mongabay, “mind-blowing” heat waves in the Mediterranean pose existential threats to dozens of species across the sea’s ecosystems.

From Mother Jones, the ugly truth about bottom trawling, a fishing practice that is extraordinarily bad for ocean life and for climate resilience.

From the Guardian, the recent announcement by the Monterey Bay Aquarium Seafood Watch, its sustainable seafood initiative, to “red-list” lobsters because of the risks the fishery poses to North Atlantic right whales. This means that the Aquarium recommends not buying lobster until the threats to the endangered whales have been mitigated, despite the lack of solid evidence that the U.S. lobster fishery has caused any right whale deaths.

From the Times, the impact of China’s massive and largely unregulated fishing fleet in international waters: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2022/09/26/world/asia/china-fishing-south-america.html

Beautiful and moving as always, thank you.

Have you ever heard of A Suitcase Full of Eels? It is an artist project here in the UK: https://eels.cargo.site/Home

This essay is so beautiful...itself a thing to cherish...a thing to wake us to what we need to preserve and care for in the weeny bit of time before it's all gone!! Thank you for these deeply moving and informative essays.