Heather and I are painting the new place this week, which has brought me to this:

“It’s a small world,” the comedian Stephen Wright used to say in his trademark monotone deadpan, waiting a moment for the audience to contemplate the cliché, “but I wouldn’t want to paint it.”

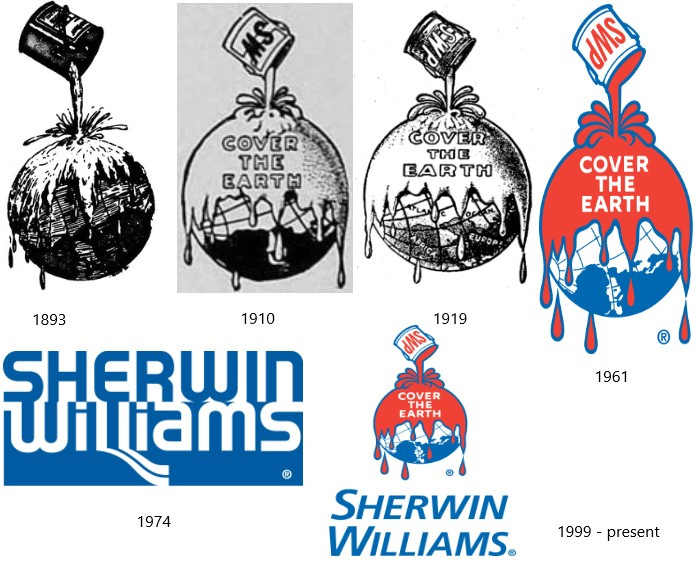

Maybe he was riffing off the Sherwin-Williams logo. Since 1893, Sherwin-Williams has represented itself with an image of a can of thick paint pouring over the Earth. In 1910 the company etched the catchphrase “Cover the Earth” into the flood. The logo’s view is god-like and odd, as if we’re looking from the Moon or space at the waterboarding of the planet. What seems to be the northern hemisphere is completely smothered but, weirdly, at closer inspection you can see that the planet is tipped on its side with Europe and North Africa visible at the bottom. The original logo was black-and-white but in 1961 it became quite vivid, with blood-red paint “spilling down from the heavens to a helpless planet,” as a brief history at Money Inc put it.

The ambitions represented by the logo – the god-like view, the hint of global conquest in the slogan – have been realized by Sherwin-Williams. According to a Statista report on the industry, they are the largest paint and coatings company in the world by revenue, earning 18.4 billion dollars in net sales in 2020. That’s up from 11.1 billion dollars in 2014, so the company’s growth prospects seem just fine.

Humans are quite busy painting their small world. 10 billion gallons of paint and coatings were sold in 2019, and the revenue forecast for the industry in 2025 is 179 billion dollars.

The logo has its critics, unsurprisingly. I count myself among them. It was cute and normal during the “Great Acceleration” of the 20th century – you know, the several decades that transformed the planet and gave us the Anthropocene – but now it just looks like the environmental equivalent of a “harmless” racist joke.

Sherwin-Williams had their own misgivings about the logo back in the 1970s, that short bright bipartisan environmental era in the U.S. when the EPA was formed, and the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act were passed. There were people marching in the streets for a healthy environment, and both politicians and corporations were paying attention. The Blue Marble photograph – a beautiful blue-green Earth floating in space – represented a new cultural focus on environmentalism. Sherwin-Williams replaced their bloodied planet in 1974 with the anemic bit of text you see in the collage above, with just their name and a couple painterly swoops at the bottom. It was a lackluster concept, so the rebranding failed and in 1979 they reverted back to their nearly century-old cheerful metaphor for planetary destruction.

50 years later, Sherwin-Williams clearly doesn’t feel the need to update its image to improve its market share, or to appear more innovative than the 150-year-old image would suggest, or to coax the newest environmental generation to buy its products. They have 4000 stores, mostly in the U.S., and I don’t think any of them are being picketed. The company has a long, detailed Sustainability Report, with the usual soft goals for reducing its impacts (greenhouse gases, water usage, etc.) and improving the lives of its workers and customers. So perhaps the company feels that those actions speak louder than logos (though removing the logo would itself be an action). And in the end, either they like the look of the logo or they like the money enough to forget about the look. The paint and coatings industry is one of many that will always increase in value so long as population and consumption keep increasing.

The industry relies on mining for natural pigment ingredients (titanium dioxide for white, metallic salts for yellows and oranges, for example) and on processing coal tars and other petroleum products for synthetic pigments. Other petroleum products are used as solvents (to make it spread more easily) and resins (to make it dry faster). Various additives are used as thickeners, anti-settling agents, anti-skinning agents, defoamers, and more. All are sourced and shipped around the planet to fill those 10 billion gallons which are, in turn, shipped around the planet. In other words, these paints cover the Earth before they even leave the can.

All of this resource usage is just for the skin of civilization, or really just one of the skins. Think about all that lies beneath the paint or resin or powdercoating or stain: construction materials, furniture, tools, boats, houses, vehicles, appliances, aircraft, and innumerable industrial applications. Each of these categories in turn is built on massive extraction of raw materials from around the globe, at a rate growing quickly in lockstep with increasing population (a net growth of about 2.5 humans per second), with increasing global affluence (esp. in China, India, and Southeast Asia), and with widespread technological growth.

Which brings me back to the I=PAT formula I mentioned several weeks ago. Total environmental impact (I) is generated by human population (P) in combination with that population’s affluence (A) and use of technology (T). Affluence is defined in this case as the level of material consumption, and technology is defined as the means by which resources are extracted and processed. It’s not a clean equation in which each factor exists independently of the others, and it doesn’t predict a particular impact level or help set sustainability goals, but it is an excellent tool for roughing out the ways in which we’ve created the Anthropocene and for thinking about how to reduce our impacts. Sophisticated improvements in recycling and transportation efficiency, for example, are a form of increased Technology that may actually reduce the impacts of Population and Affluence.

I=PAT deserves its own discussion, but I wanted to mention it here as a way of plugging my little essay on paint into the larger guide to the Anthropocene. There are so many other ways in which we cover the Earth: with agriculture, roads and dams and cities, radionuclides from atomic bomb tests, introduced and invasive species, antibiotic-resistant microbes, and much much more. At the root of all this is a burgeoning human population, able to go anywhere, live anywhere, bulldoze anywhere, and erase anywhere. And now our single largest Impact is our heating of the planet. Replace the Sherwin-Williams paint can with a hairdryer and you get the picture.

I want to wrap up here with what will seem like a pretty dark analogy. I mentioned antibiotic resistance a moment ago as example of one of our many ubiquitous impacts. Take a look at this video of bacteria racing through increasingly high concentrations of antibiotic-laced agar. The video was produced by a lab at Harvard Medical School, and is called “The Evolution of Bacteria on a ‘Mega-Plate’ Petri Dish.” Keep the sound on to hear the experiment being explained.

This is an incredible demonstration of evolution in action. It helps me understand how the flood of antibiotic-laced waste from cities and farms into rivers has permanently altered wild populations of microbes. I see also, in metaphor, the human spread out of equatorial Africa into harsher temperate and then polar environments. And, finally, I’m reminded that our spread across the globe is at heart a natural phenomenon. It’s starting to look catastrophic for the rest of life on the planet, and depending on how we respond in the next decade or two, possibly catastrophic for us as well. But it’s natural, in the way that a forest fire or pandemic is natural. The fire or infection or highly successful generalist species, if not controlled, races through its environment until it exhausts its fuel or hosts or resources.

So yes, it’s a small world, and getting smaller every year. We’ve painted just about all of it now.

One final note on the logo: I don’t know why the Sherwin-Williams planet is tilted on its side, or why they’ve kept it that way, with just parts of Africa and Europe visible beneath the flood, for a century and a half. Maybe they’re indicating that the company has expanded out from North America, which lies directly under the paint can. Regardless, what I find particularly strange is that according to a Fast Company article Sherwin-Williams paints are available globally except in much of Europe and Africa. Make of that what you will.

A Good Idea

This book looks wonderful. I haven’t read it yet, but plan to. Dara McAnulty is a brilliant young naturalist with a gift for talking about both the natural world and his autism. Check out a profile in the New York Times here: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/07/books/dara-mcanulty-diary-of-a-young-naturalist.html

Links:

Two flimsy histories of the Sherwin-Williams logo:

Statista numbers on the paint and coatings industry: https://www.statista.com/topics/4755/paint-and-coatings-industry/

Sherwin-Williams sustainability report: https://sustainability.sherwin-williams.com/corporatesocialresponsibility/report/

Fast Company article: https://www.fastcompany.com/1663585/you-asked-and-rick-answers-a-revamp-of-the-sherwin-williams-logo

In Other Earth-Shattering News:

A very, very extensive FAQ-style analysis of the environmental crisis, with an emphasis on climate, from the activist organization Extinction Rebellion: https://extinctionrebellion.uk/the-truth/the-emergency/

Some thoughts from The Guardian on choosing sustainable foods: https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2021/jun/29/eat-this-to-save-the-world-the-most-sustainable-foods-from-seaweed-to-venison

The incredibly shrinking cryosphere (Earth’s icy regions): https://www.livescience.com/earth-ice-extent-shrinks.html

Predicted increase in U.S. coastal flooding in the 2030s: https://scitechdaily.com/dramatic-surge-in-u-s-coastal-flooding-projected-to-start-in-2030s/

Concerns about oil spills in a warming Arctic: https://scitechdaily.com/oil-spill-in-the-canadian-arctic-could-be-devastating-for-the-environment-and-indigenous-peoples/

Thanks for keeping the essays and insights coming, particularly when busy moving. Wishing you a happy new home! Recent missives remind me of conversations found in McPhee's "Encounters with the Archdruid" and the costs of our lifestyles, even when trying to be conscientious. Paint is such a simple, common thing that we've all employed, yet as it continues to cover the world at an astounding rate (and the associated industrial development that is leading to loss of clean air and water), I appreciate writings like yours which help to inculcate some bigger sense of responsibility and hope that development and environment could go hand-in-hand.

In searching for something to help me visualize what 10 billion gallons of paint would look like, I came across this tidbit: we Americans use 322 billion gallons of water each day! (https://medium.com/ensia/america-uses-322-billion-gallons-of-water-each-day-heres-where-it-goes-35cba911da48). A whole different conversation, I know, but wow!

Got a lot out of "Footprints" and look forward to reading more. Good recommendations!