Hello everyone:

For context on the coup in DC, the latest brilliant posts by Timothy Snyder and Heather Cox Richardson are enlightening. If you’re feeling overwhelmed and helpless, don’t forget that that’s part of the Project 2025 strategy. Remember too that some of the noise is bluster for the cameras (signing meaningless documents), some is a scare tactic (“new” ICE raids that happened a decade ago), some is meaningless (the oil market is already glutted), and some will be reversed. That said, things will get worse before they get better. But we can help make it better. For now, I suggest finding some good work to do, and pacing yourself.

Also, please note that to illustrate this week’s topic I’ve included some images of trapped and dead animals. They are not bloody or gory, but you may not like them. They’re included because they portray the hard side of the ecological repair we all want to happen.

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read this week’s curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to the writing:

Just as war stories are told mostly by the victor rather than by those who fall en masse to the weapons of destruction, the animals and plants we slaughter for ecological reasons are silent in the conservation narrative. Some of us may speak for them, but even the best of us are not reliable narrators. We cannot separate ourselves from their fate.

As a result, their story is never simple, except for this: All life wants to live.

In the Anthropocene, “invasive” species are really introduced species. In nearly every case, we have been directly or indirectly responsible for shifting a plant or animal to where it does not belong. And we should not forget that these species are still marvels of life’s endless creativity and intelligence. Kudzu and cheatgrass, rat and zebra mussel, carp and stoat are all astonishing and beautiful. If we find them ugly in their new locations, it’s because of what we, not they, have done.

But the suffering of threatened native species and their disrupted ecological communities cannot be ignored. Espousing the otherwise profound wisdom of valuing all life, when work to repair the harm is possible, is a kind of willful blindness. Taking responsibility for ecological rupture allows for at least a little justice for the land, and it limits further harm. Doing nothing, when there is something to do, is an ethical failure.

In any discussion about the ethics of reshaping an ecosystem to protect native species, then, we are obliged to weigh the actions and consequences for everyone involved. But this is not really a story with two sides, native and nonnative. It is a story of the current dominant culture of Homo sapiens sapiens, native nowhere and everywhere, wreaking havoc and working in small ways to make amends for some of that havoc.

As with so many Anthropocene decisions, we're trapped between bad choices that each in their own way seems antithetical to life.

The “invasive” story is far more complicated than I have time to fully explore here. In brief, though, we should remember first that some introduced species settle in quietly and gently, causing little fuss or damage. Others (like “white man’s footsteps”) even become valued members of their new community, feeding life rather than disrupting it.

But there is the darker, broader truth too. Much of what we’ve changed will never change back, because 1) we continue to spread out and disrupt, 2) some introductions are so widespread and deeply rooted that reversal is impossible, 3) extinctions of local species are (likely) forever, and 4) a warming world that generates planetary disruption - forcing plants and animals to adapt, move, or die - will not cool to pre-industrial levels in the foreseeable future.

Here in coastal Maine, Heather and I sometimes help cut back proliferating nonnative vines and shrubs like Asiatic bittersweet, honeysuckle, and black swallowwort, but it generally feels like bailing a sunken boat against the incoming tide. Worse, we’re watching hemlock, beech, and ash trees across eastern North America suffer the same sad fate as chestnuts and elms - helpless against nonnative pests - and altering entire forest systems as they die off. The good news, here as elsewhere, is that good work is being done quietly by dedicated scientists, conservation biologists, and community volunteers to find solutions and stem the tide.

The fight against invasive/introduced species is really a secondary action amid our larger war against the natural world. And it is often a desperate one, because those good folks engaged in eradication efforts on behalf of a beleaguered ecosystem or species face an uphill battle against both 1) those resilient species we have shifted and 2) the broader human culture which continues its planetary-scale disruption.

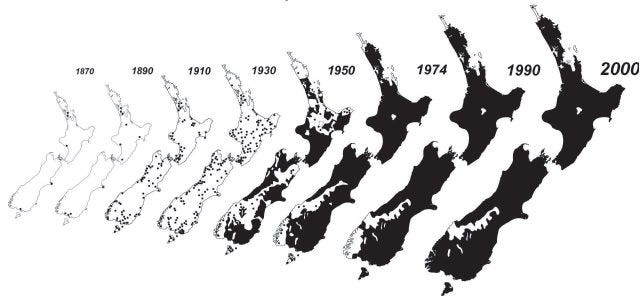

The aggressive control of nonnative species is being undertaken in landscapes that are vastly different than they were just a few hundred years ago, because of how we’ve chosen to live. The beautiful pastoral countryside of Aotearoa New Zealand, as in the picture below, was just two centuries ago a lush bird-filled native forest. The farms, pastures, and livestock are all alien. The ongoing heroic effort to remove certain aliens (rats, possums, stoats, weasels, ferrets, feral cats, and numerous plant pests) from those landscapes does not unmake that larger alien reality.

And then there is the ethical problem that far too often the fix for suffering is more suffering.

And yet, as I see it, the cruel work must be done where it can be done. No, it’s not the introduced species’ fault, and no, removing them does not change much of the harm caused by 8.2 billion resource-hungry humans. But the work must be done, and it must be done as much as possible, and as soon as possible.

These are the unsettling ethics of ecological triage, where care and duty and a do-no-harm attitude meet the train wreck of widespread and ongoing extinctions. The best outcome is to accomplish the work with as little cruelty as possible.

To agree with me on this, I think, you need a sense of what’s been lost amid the havoc, and of what can be gained by the slaughter. I tried last week to provide a meaningful sketch of New Zealand’s astonishing natural world - mostly its birds - and of how much has been gained already on the islands where rats and other threats have been eradicated. Given a chance, native plant and animal populations can bounce back quickly. That is a damn good reason for celebration and joy. The closer a species is to extinction, though, the harder that recovery will be. Thus the push to act now.

As with all hunting, fishing, and conservation fieldwork, there is an art and a craft to predator control. Patience and diligence are required virtues. You need to know the animals’ behavior well enough to monitor for their presence, either to find and shoot them or to set the right traps and poisons in the right places. You need to master the art of trapping itself, including knowing how not to harm the animals the work is meant to protect. You need to monitor the traps, perhaps daily and perhaps for years at a time, and you need to observe over time the changes to the forest as a result of your control work. If total eradication is your goal, the last 10% may take as long and cost as much as the first 90%.

Now imagine that kind of attention, time, patience, and diligence applied to every nook and cranny of an entire nation overrun with introduced predators. New Zealand is the size of Colorado (a little larger than the UK and a little smaller than Japan), but features an array of complex terrains, including rainy fjords, dense forests, glaciated and volcanic peaks, and rolling farm country. All of this makes Predator Free 2050 the most ambitious conservation project in the world.

But the reward would be beyond measure. The predators that the project seeks to eradicate - possums, stoats, weasels, ferrets, and rats - kill an estimated 25 million native birds each year and are a significant reason why 4000 native New Zealand animal and plant species are threatened or at risk of extinction.

To put all of this into context, I’ll focus on one of the key target species of Predator Free 2050 - the possum - and how it’s targeted.

Australian brushtail possums were introduced in the 1800s to provide a local fur industry. There are now about 30 million of them, six times the human population, spread through nearly every hectare in the country. Their numbers may have been as high as 70 million in the 1980s, when you could pretty much hear the forests being chewed to the nub. That population estimate “was always a back-of-the-envelope figure,” one expert has said. “The number of possums is not relevant,” he added. “The amount of damage they do is.”

Possums are nocturnal, and collectively eat about 21,000 tons of vegetation a night, often stripping trees bare. They consume the nectar and berries native birds rely on, and they can raid nests for eggs, chicks, and sometimes adults. They are also a primary vector for the spread of invasive plant seeds and bovine tuberculosis.

A 1992 New Zealand Geographic article acknowledged the cuteness of this ecological nightmare, describing possums as “a South Pacific version of the teddy bear,” but concluded that “with forest destruction all around, it’s a case of the possums or the trees.”

Killing possums has been a mainstay of NZ culture for several decades. (When I traveled around the South Island in the late 1990s, I never killed a possum, but people joked about swerving to hit as many as possible when driving at night.) The government now spends about $110 million per year on possum control. The animals are shot (warm nights after a rain are best), trapped (the fur is highly valued), and poisoned.

There is a deep online conversation - and plenty of sources for advice - about which method is best, what kind of traps or bait to use, how and where to set your traplines and bait stations, etc. Predator Free NZ has a good page to start your search, and the NZ Department of Conservation (DOC) has a full run-down of trap and toxin choices. If you’re not familiar with hunting and trapping, and haven’t been to NZ, the flood of information will seem strange and barbaric, but it’s a necessary cultural response to a national environmental crisis.

None of these methods - shooting, trapping, poisoning - have been sufficient on their own to eradicate possums from an area. Shooting is labor-intensive, and some possums are bait-shy or trap-shy. It takes a prolonged, multifaceted campaign to finish the job.

To reduce the cruelty in all this, there are strict regulations on the use of traps and poisons, widely-available instruction for landowners and others new to predator control, and a steady evolution in the design of both traps and poisons. But hunting/trapping culture is complex, and includes on one hand the careful training of the next generation to carry on the good work of environmental restoration, and on the other hand the celebration of (dead) possum-throwing contests at the local school.

Poisons are perhaps the most important tool in the eradication toolbox because they can be used across large and hard-to-access areas through aerial application. They are also the most controversial. Some cyanide poisons can kill in seconds, but the most common toxin used in New Zealand’s campaign against these nonnative mammals is sodium fluoroacetate, known as 1080, and depending on several variables may take much longer to kill. 1080 is a synthetic version of a natural plant toxin. The NZ DOC provides a robust defense of its use, noting that 1080 does not accumulate in the environment and calling it safe and effective, biodegradable, and generally ideal for NZ conditions (rugged terrain with no native mammals).

A more comprehensive DOC document on 1080 explains that its use is supported by NZ conservation groups and by extensive research. Also, the poison is particularly effective in predator plague years:

In a mast year, when there is plenty of food available, rats can have litters of up to 14 pups five times a year. When the seeds run out, the rats switch to eating native wildlife. Stoats also increase after beech masts as they feed on rodents and then switch to native birds.

“We face a choice,” the DOC writes about the ethics of poisoning predators: “leave pests unchecked and have silent, bare forests, or control predators and help native species to survive… As we make progress towards eradicating rats, stoats and possums to achieve Predator Free 2050, the need for ongoing predator control will be reduced.”

I’ve been thinking about all this here in wintry Maine while checking mouse traps in our basement and attic. I hate to admit it, but sometimes the traps snap shut on mice in awkward, slow-to-die ways. And sometimes, if we find them soon enough, we have to kill them to end the suffering. In fact, in a rather strange and ugly coincidence, this happened as I was drafting this paragraph. I heard the trap snap in the basement, but could tell the mouse was still struggling. So I dealt with it.

But other than trying to block their access into this old house, the traps are the best method we have available. I won’t use poison because it kills slowly and could affect whoever eats the mice when they leave the house to die. And I will never use sticky traps, which I think is a practice more cruel than anything I’ve read about in New Zealand. Honestly, I think they should be banned.

The good news is that as the Predator Free 2050 project intensifies, the control technologies have been evolving to be more efficient, effective, and humane. A rat-specific poison in in development, and there are even AI-equipped traps entering the market that only kill after recognizing that the victim is not a native bird or domestic pet. More importantly, perhaps, new possum and rat traps can work independently for months, resetting and rebaiting automatically after an animal has been killed, all while sharing their status and kill data.

The possum or rat climbs up to the baited trap, sticks their head in, is killed, and then drops to the ground, making room for the next victim. In a recent National Geographic article, one expert estimated that these traps are 49 times more effective than the previous models:

“It’s game-changing technology,” he said. “We used to say you can’t trap your way to predator elimination. These traps are challenging that idea.”

I’m not sure if anyone is confident that Predator Free 2050 will meet its eradication goals in just 25 years. But tens of thousand of New Zealanders, Māori and Pākehā alike, are working toward those goals. It helps that there is an economic logic as well as an environmental one. Possum fur is an incredibly warm and soft material, now most often turned into fiber and blended with merino wool into high-end, durable, beautiful cold-weather clothing. There is some effort too to use possum meat for pet food. Even if left in the forest to decompose, the animals serve the nation’s larger goal: returning the sun’s energy into the native ecosystem.

I’ll close by returning to some wisdom I offered last week, from an ecologist quoted in the recent National Geographic article:

there are two kinds of animal welfare to consider—that of the predator and that of the prey. The harm that predators inflict on native species far exceeds the harm we inflict in managing them, he argues. “The presence of mammalian predators in Aotearoa is an historical environmental injustice,” Russell said. “Just as we try to correct historical social injustices, I believe we should try to correct historical environmental injustices.”

And I’ll add, from the same article, a final ethical note from the Predator Free 2050 manager for the DOC:

You make a choice, and it’s an active choice either way. Indigenous species or animals that don’t belong here - which one will it be? Either way you’re condemning animals to death.

For a homegrown view on all this, take a look at two excellent NZ-base newsletters: The Turnstone by Melanie Newfield, and

by Jane Pike. Newfield has a recent piece, “My enemy’s enemies,” which offers an excellent primer on biocontrol and some helpful reminders of the value of taxonomy and risk assessment. And Pike has a new essay - “36 is Another Word for Hope” - meditating on the meaning of home in the context of the repatriation of a small flock of Tieke (South Island Saddlebacks) from an offshore island to a mainland ecosanctuary near her farm. Both writers are well worth your time.Finally, I’ll close out with a few good-news stories adjacent to the large-scale conservation work in Aotearoa New Zealand:

Whales are people too: Māori and other Pacific Indigenous leaders have signed a treaty recognizing the legal personhood of whales. “Under the treaty,” writes ABC Pacific, “whales will be recognised as a legal entity with rights and legal standing if harmed, something advocates hope will help ensure their legal protection.”

Founding modern conservation on traditional practices: The Hinemoana Halo Ocean Initiative, a project of Conservation International Aotearoa and Māori and other Pacific peoples, was a driving force behind the new whale treaty. “Our shared goal, they write, “is to advance a region-wide movement to reconnect with our common ocean heritage and legacy as kaitiaki (guardians) of the moana. This partnership will establish a marine recovery plan that will accelerate the recovery of populations of taonga (sacred) species, from whales to sea lions, dolphins, and manta rays, in Aotearoa’s coastal waters.”

Fools and Dreamers: I highlighted this half-hour documentary a few years ago, but it’s worth cheering on again. Fools and Dreamers is a wonderful upbeat story of regenerating native forest on old tired farmland and creating the 3000 acre (1250 hectare) Hinewai Reserve. Be sure also to check out Happen Films, the filmmakers behind the project; their website has dozens of other short films on living more gently and wisely on the land. Here’s the Fools and Dreamers trailer:

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

First, this:

Just for some perspective on all this Earthly drama, from ScienceAlert, a mind-melting but readable bit of news on the shape of the Universe: It may not be expanding after all, but instead is “lumpy” with vast regions that experience time differently. As we telescope our inquisitive consciousness through the stars, what looks like an expanding universe might actually be “bubbles” of space billions of years older than ours. Dark matter and dark energy - which are really placeholder names for placeholder concepts - may not exist at all.

And now for some of the drama:

If you’re wondering who’s keeping track of every Trump administration attack on climate regulations, check out “A Running Tally of Trump’s Climate Impacts” from Drilled, and the Climate Backtracker from the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at the Columbia Law School, which “identifies steps taken by the Trump-Vance administration to scale back or wholly eliminate federal climate mitigation and adaptation measures.”

Likewise, if you’re wondering who’s keeping track of deforestation (and reforestation) around the globe, dig into Global Forest Watch, which “offers the latest data, technology and tools that empower people everywhere to better protect forests.” They offer a suite of tools for journalists, NGOs, companies, and policymakers to observe and assess in real time changes to forests anywhere in the world.

From Undark, a sadly compelling argument that kelp farming is an ineffective or even harmful practice for sequestering carbon and mitigating Earth’s warming. I don’t know enough about the debate to have an opinion, but have been hopeful that large-scale kelp farming was a strong win-win for biodiversity and the climate. The biodiversity angle isn’t discussed in this piece, but it does make a good case that the flaws in the kelp-will-save-the-world climate plan outweigh its benefits.

Some upbeat news:

From the Bay Journal, brook trout in the headwaters of the Potomac are thriving after 19 years of painstaking stream restoration work in the “nooks and crannies” of West Virginia streams. Read the article to get a sense of just how much effort and patience was required to restore all this habitat. This is the kind of work that should be happening everywhere. (Full disclosure: My nephew spent a few years on this project.)

From the Volts podcast, a really great, funny, thoughtful, and informative conversation about the capability of a clean-energy grid to boost cybersecurity, though really it’s a wide-ranging discussion that’s well worth your time regardless of your interests in either clean energy or cybersecurity.

From Nautilus, an interview with a photographer producing extraordinary work, both strange and beautiful, combining microscopic imagery with color photography, illustrating hopeful stories about food and agriculture.

From Mongabay, a good-news story of villages in Nepal learning to coexist with migratory elephants, thanks to better policy and education.

As a cat-lover AND a bird-lover, I believe all cats should be kept inside, at all times. If there are feral populations that cannot be housed because of feral cat behaviors or a lack of willing adopters, then I am comfortable with humane methods of predator eradication. I completely understand what island communities and others are trying to do to remove invasive predators and I've seen the fantastic results on a predator-free island off of New Zealand's coast, Tiritiri Matangi.

But I'm at a total loss for the ongoing attempted eradication of Barred Owls out West. Barred Owls were not introduced by humans; they out-competed Spotted Owls BECAUSE humans altered the landscape where Spotted Owls lived. Barred Owls are just better at living in what's left of that environment. There are going to be many more creatures that out-compete other creatures in the near and distant future because of the continued presence of humans on the planet. But the killing of 450,000 Barred Owls for surviving in these times seems like a fool's errand. The reward for adaptation should not be eradication in all cases.

Thoughtful and sensitive writing about a difficult topic. Rewilding isn’t always all upsides, and sometimes we have to reckon with hard ethics. I appreciate this nuanced piece.