Hello everyone:

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read some curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

One of our favorite walks in this area is the La Verna Preserve. The trail winds for a mile or two through mixed forest, crossing a couple wetlands, on its way to the sea, where a broad view takes in both the spruce-tipped islands dotting Muscongus Bay and the open horizon of the Gulf of Maine. The preserve’s sign notes that the original owner of the land named it “in honor of Saint Francis of Assisi for their shared love of nature and God’s creatures.” This beautiful access to forest and sea is a gift Heather and I are quite conscious of every time we walk the path.

The original La Verna, in the Appennine Mountains of Tuscany, was a 13th century sanctuary for Francis, who became known for his love of animals and the natural world. (World Animal Day, “an international day of action for animal rights and welfare,” is held each year on October 4th, Francis’ feast day.) Still today, the Forest Monumental de La Verna that surrounds the shrine is a biodiverse refuge maintained by the Fransciscan order.

The name La Verna predates Christianity and even the Romans. It’s derived from the Etruscan goddess Laverna, an underworld deity, who well into the Roman era was known as the goddess and protector of thieves. Francis’ sanctuary was built atop the shrine to Laverna. This sounds like the standard burial of pagan history by the church, and perhaps it was, but it’s worth noting that Laverna was also considered to be the protector of refugees, something that Francis, and the modern Pope who took his name, may have considered holy work.

There is much in Pope Francis’s thinking and legacy that distances me from him. The Catholic church has stained much of human history with blood and false ink, all while empowering the delusion of human supremacy. The church’s view on population is as medieval as the pronatalists’. And, as I've written here before, I have neither religious bones nor flesh, nor even ideas (the least of our body’s miracles). For better or worse, I was raised free of any church - each with its own steeple tuned to a particular holy frequency - and unbound by their texts. As the poet Mary Oliver said, “the universe is full of radiant suggestion,” but I am wary of any human claim to contain it in a word or book.

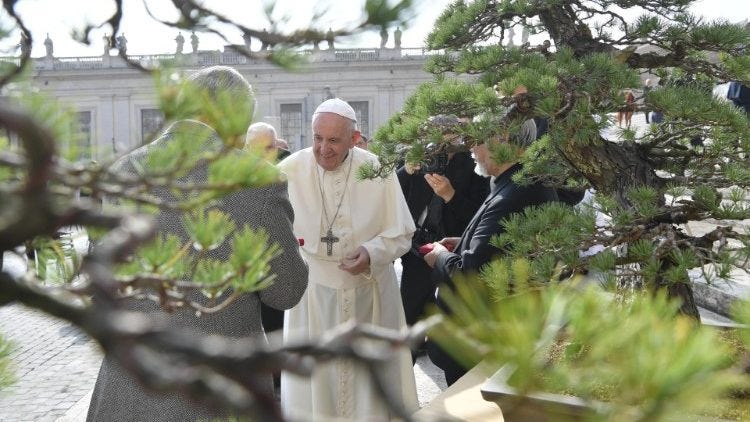

But Pope Francis, like our local walking trail named after his namesake’s sanctuary, has been a gift. He has been a gift to the Earth and to those of us who care about the fate of all life. He has been an astonishment on the world stage, speaking clearly for the poor and for the natural world, and speaking firmly against the cruelties of capitalism, and against the failures of global leadership to face up to the existential climate and biodiversity crises.

I have not written an elegy for the environmentalist Pope Francis, who died on Easter Monday, in part because others have done a fine job of it already. You would do well to start with

’s recent “Pope Francis and the Sun,” in which he calls Francis “perhaps the world’s greatest environmental champion,” and describes Laudato Si’ - On Care for our Common Home, Francis’s book-length papal encyclical on the environment, “arguably the most important piece of writing so far this millennium.” But I love especially how McKibben elegantly praises the Pope’s work to remind us to care for all of life:I think Francis’s project for the earth—a recovery of fellow feeling, with a special attention to the poor—is the only thing that can save us over time.

And I’d recommend as follow-up, from Mongabay, Justin Catonoso’s longer, more comprehensive appreciation of the Pope’s long record of speaking for the community of life, for the poor and working classes who rely on it, and against the rich and powerful who have built a society that devalues and demeans both. “While his death leaves a vacuum of moral environmental leadership within the globe’s largest religion,” Catonoso writes, “the words of Francis still echo through tropical rainforests and grasslands, across rivers and oceans.”

Keeping with the Franciscan ethic of simplicity, I want to offer some of those words this week, so that you hear the echoes and carry them forward as you walk your path. I’ll keep the commentary to a minimum, but will highlight (in bold) sentences or phrases that seem particularly resonant.

Remember, as you read the Pope’s exhortations to care for the Earth, that they were sent out to the 1.4 billion Catholics in the world, and to anyone else who would join together in common cause.

From Laudato Si’, 2015:

To start, here are two excerpts in which Pope Francis sounds far more ecological than theological:

It cannot be emphasized enough how everything is interconnected. Time and space are not independent of one another, and not even atoms or subatomic particles can be considered in isolation. Just as the different aspects of the planet – physical, chemical and biological – are interrelated, so too living species are part of a network which we will never fully explore and understand.

When we speak of the “environment”, what we really mean is a relationship existing between nature and the society which lives in it. Nature cannot be regarded as something separate from ourselves or as a mere setting in which we live. We are part of nature, included in it and thus in constant interaction with it.

Here he is on the value of asking “pointed questions” of ourselves in order to better articulate what kind of world we want to leave for our children:

What is the purpose of our life in this world? Why are we here? What is the goal of our work and all our efforts? What need does the earth have of us? It is no longer enough, then, simply to state that we should be concerned for future generations. We need to see that what is at stake is our own dignity.

And a fine answer to those pointed questions:

There is a mystical meaning to be found in a leaf, in a mountain trail, in a dewdrop, in a poor person’s face. The world sings of an infinite Love: how can we fail to care for it?

On what this immature, unrestricted thing we call civilization is doing to the community of life that nurtured it:

The earth, our home, is beginning to look more and more like an immense pile of filth.

On how the necessary transformation of civilization begins with a wholehearted embrace of empathy:

Many things have to change course, but it is we human beings above all who need to change. We lack an awareness of our common origin, of our mutual belonging, and of a future to be shared with everyone. This basic awareness would enable the development of new convictions, attitudes and forms of life. A great cultural, spiritual and educational challenge stands before us, and it will demand that we set out on the long path of renewal.

We must regain the conviction that we need one another, that we have a shared responsibility for others and the world, and that being good and decent are worth it.

On the necessity of weaving social justice into environmental repair:

Strategies for a solution demand an integrated approach to combating poverty, restoring dignity to the excluded, and at the same time protecting nature.

On the need to respect and care for climate refugees and those fleeing “from the growing poverty caused by environmental degradation”:

They are not recognized by international conventions as refugees; they bear the loss of the lives they have left behind, without enjoying any legal protection whatsoever. Sadly, there is widespread indifference to such suffering, which is even now taking place throughout our world. Our lack of response to these tragedies involving our brothers and sisters points to the loss of that sense of responsibility for our fellow men and women upon which all civil society is founded.

On how the full breadth of humanity must be brought to bear in solving (or at least resolving) the problems of a damaged Earth:

Given the complexity of the ecological crisis and its multiple causes, we need to realize that the solutions will not emerge from just one way of interpreting and transforming reality. Respect must also be shown for the various cultural riches of different peoples, their art and poetry, their interior life and spirituality. If we are truly concerned to develop an ecology capable of remedying the damage we have done, no branch of the sciences and no form of wisdom can be left out, and that includes religion and the language particular to it.

On equating the Earth with the downtrodden:

We have come to see ourselves as her lords and masters, entitled to plunder her at will… This is why the earth herself, burdened and laid waste, is among the most abandoned and maltreated of our poor.

From Laudato Deum, 2023:

In Laudato Si’, a gentler document, Francis had called on Catholics to “better recognize the ecological commitments which stem from our convictions.” But several years later, in Laudato Deum, the Pope was unhappy that too little was being done, and his tone grew more stern:

Eight years have passed since I published the Encyclical Letter Laudato Si’, when I wanted to share with all of you, my brothers and sisters of our suffering planet, my heartfelt concerns about the care of our common home. Yet, with the passage of time, I have realized that our responses have not been adequate, while the world in which we live is collapsing and may be nearing the breaking point.

Seeing that there was too little empathy for the Earth and the poor, he chastised society for its hubris:

For when human beings claim to take God’s place, they become their own worst enemies.

And he chastised those who stood in the way:

International negotiations cannot make significant progress due to positions taken by countries which place their national interests above the global common good. Those who will have to suffer the consequences of what we are trying to hide will not forget this failure of conscience and responsibility.

He described the plain facts:

Despite all attempts to deny, conceal, gloss over or relativize the issue, the signs of climate change are here and increasingly evident.

Yet we can no longer doubt that the reason for the unusual rapidity of these dangerous changes is a fact that cannot be concealed: the enormous novelties that have to do with unchecked human intervention on nature in the past two centuries.

And he called out those who have pretended to care about the crisis, but have done too little:

We must move beyond the mentality of appearing to be concerned but not having the courage needed to produce substantial changes.

He doubled down on his eloquent criticism, in Laudato Si’, of a society driven by technology and human expansionism rather than by something moral and vital. Here in Laudato Deum, he writes that the technological impulse, with its existential cost to life, is only worsening:

Artificial intelligence and the latest technological innovations start with the notion of a human being with no limits, whose abilities and possibilities can be infinitely expanded thanks to technology. In this way, the technocratic paradigm monstrously feeds upon itself.

…the greater problem is the ideology underlying an obsession: to increase human power beyond anything imaginable, before which nonhuman reality is a mere resource at its disposal. Everything that exists ceases to be a gift for which we should be thankful, esteem and cherish, and instead becomes a slave, prey to any whim of the human mind and its capacities.

And he asked us to reconsider what technology is for, and whether the power it provides us is either meaningful or healthy:

We need to rethink among other things the question of human power, its meaning and its limits. For our power has frenetically increased in a few decades. We have made impressive and awesome technological advances, and we have not realized that at the same time we have turned into highly dangerous beings, capable of threatening the lives of many beings and our own survival. Today it is worth repeating the ironic comment of Solovyov about an “age which was so advanced as to be actually the last one”. We need lucidity and honesty in order to recognize in time that our power and the progress we are producing are turning against us.

He pointed out the self-serving actions of industry:

The ethical decadence of real power is disguised thanks to marketing and false information, useful tools in the hands of those with greater resources to employ them to shape public opinion.

And he pointed out the tragedy of the success of those actions:

In recent years, we can note that, astounded and excited by the promises of any number of false prophets, the poor themselves at times fall prey to the illusion of a world that is not being built for them.

He rejected the fossil fuel industry’s talking points, and spoke out in support of environmental protests:

Once and for all, let us put an end to the irresponsible derision that would present this issue as something purely ecological, ‘green,’ romantic, frequently subject to ridicule by economic interests. Let us finally admit that it is a human and social problem on any number of levels. For this reason, it calls for involvement on the part of all. In Conferences on the climate, the actions of groups negatively portrayed as “radicalized” tend to attract attention. But in reality they are filling a space left empty by society as a whole, which ought to exercise a healthy “pressure”, since every family ought to realize that the future of their children is at stake.

Again and again, he reminded Christians that human society is embedded in, and embraced by, the full range of life on Earth:

The Judaeo-Christian vision of the cosmos defends the unique and central value of the human being amid the marvellous concert of all God’s creatures, but today we see ourselves forced to realize that it is only possible to sustain a “situated anthropocentrism”. To recognize, in other words, that human life is incomprehensible and unsustainable without other creatures. For “as part of the universe… all of us are linked by unseen bonds and together form a kind of universal family, a sublime communion which fills us with a sacred, affectionate and humble respect”.

And he made it clear that the only path forward in the real world - rather than the tottering fictional world busily being built for us - is to remember what it means to live with the planet, rather than merely on it:

Let us stop thinking, then, of human beings as autonomous, omnipotent and limitless, and begin to think of ourselves differently, in a humbler but more fruitful way.

I’ll close with a quotation from Evangelii Gaudium, 2013, that I think beautifully describes our connection to the rest of life. I don’t know about you, but I fully recognize what he means by feeling the harm to the soil or, especially, feeling the loss of a species like the loss of some part of me:

We human beings are not only the beneficiaries but also the stewards of other creatures. Thanks to our bodies, God has joined us so closely to the world around us that we can feel the desertification of the soil almost as a physical ailment, and the extinction of a species as a painful disfigurement. Let us not leave in our wake a swath of destruction and death which will affect our own lives and those of future generations…

Small yet strong in the love of God, like Saint Francis of Assisi, all of us, as Christians, are called to watch over and protect the fragile world in which we live, and all its peoples.

Pope Francis liked to reiterate two fundamental ideas: “Everything is connected,” and “No one is saved alone.” (I hear Robin Wall Kimmerer’s “all flourishing is mutual” echoing through the latter phrase.) With that in mind, and with his own poetic flourish, he writes:

Hence, there is a mystical meaning to be found in a leaf, in a mountain trail, in a dewdrop, in a poor person’s face.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

From NPR, an excellent follow-up to my essay last week on pronatalism. This piece explores in greater depth the weird mash-up of U.S. groups joining forces to push for a higher birthrate among white Americans, and articulates nicely the darker corners (white supremacy, racism, fear of “white extinction,” etc.) of the movement.

From Anthropocene, an excellent new analysis of the benefits of converting some of the New-York-state-sized portion of the U.S. growing corn for ethanol to solar energy production. Ethanol is an environmental nightmare, an inefficient boondoggle, a political farce, and an utter waste of land. Converting just 3.2% of the current corn-for-ethanol acreage to solar would produce the same amount of energy as generated by the remaining 96.8%, while more than tripling the amount of solar energy in the U.S. grid. Converting less than half (46%) of corn-for-ethanol land to solar would “generate enough energy to reach the 2050 decarbonization goal for the US.”

From Grist, as I feared (and wrote about recently), the Trump administration has announced that it’s fast-tracking deep sea mining, after the recent decisions by The Metals Company and Impossible Metals to reject the slow, deliberative international process for assessing how best (or whether) to permit such activity. The companies turned instead to the U.S., where profit motive and soulless ideology are wreaking havoc on all environmental protections. The consequences of this incredibly irresponsible decision will, if carried out, be felt in the abyss for millions of years.

From the Guardian, it’s vital to activate the “silent majority” of people across the globe who are concerned about climate change and who want their leaders to act on those concerns. A survey that interviewed 130,000 people across 125 countries found that 89% of respondents thought their governments “should do more to fight global warming” but mistakenly believe that they are in the minority. The Guardian and dozens of other newsrooms around the world are partnering in the 89 Percent Project to inform their readers that they are not alone and that they have the power to effect change, rather than staying home in a “spiral of silence.”

From Inside Climate News, an overview of the onslaught of actions in the first 100 days of the Trump administration intended to erase, decimate, diminish, or at least undermine environmental regulation, habitat protection, and climate action across the entire U.S. government. The level and speed of destruction is intentional, like teen looters turning the furniture over in a race to do as much damage as possible before the adults show up.

Also from Inside Climate News, a conservation story here in New England: The Magalloway River Conservation Corridor will add 78,000 acres in the Rangeley Lakes region to a half million acres of protected land in Maine and New Hampshire. This will build out a large-scale wildlife corridor, restrict harmful development in the region, and protect some of the best brook trout habitat in the country.

From National Geographic, the strange, difficult, and tragic story of invasive camels in Australia being shot by the hundreds.

Thank you for honoring this honorable man. We can only hope (and for those of us who pray, also pray) that the Conclave chooses a papal leader who continues in Pope Francis’s path.

Yes, thank you Jason for highlighting Pope Francis’s work. Beautiful, powerful and very inspiring!