Hello everyone:

The quote of the week is a classic from Wallace Stegner in This is Dinosaur, back in 1955:

We are the most dangerous species of life on the planet, and every other species, even the earth itself, has cause to fear our power to exterminate. But we are also the only species which, when it chooses to do so, will go to great effort to save what it might destroy.

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read some curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

Back in my teaching days, I had a piece of advice I liked to offer my students: What we practice is what we become. (This was at a very small private school for high school boys where we offered social and emotional growth in a family-sized academic setting.)

There are other ways to express the idea. The Daily Stoic reverses it: You become what we practice. The good folks at On Being built a set of virtues to live by around their concise What we practice, we become. You may have your own version.

This is good news, I told my students, because it means that we can change our lives by practicing something new right now. We enact a new story by changing habits.

Those teens who may or may not have been interested in my unsolicited advice are no different from the rest of us. We have societal/civilizational habits that are upending life on this planet, and we’ve been far too slow to admit what needs to change and recognize how to do it. Much of this is due to vested interests making change difficult for ordinary folks, but we each live in a pattern of movement and resistance to movement – momentum and inertia – that we are loathe to disrupt.

A body in motion wants to stay in motion, especially if it’s a profitable corporation. A body at rest wants to stay at rest, especially if it’s on the couch.

I’ve been thinking about this while driving around and witnessing the annual late-summer and autumn ritual of mowing fields. I’m not talking about lawns, though lawns are definitely worth talking about. I’m talking about those tall fields and meadows that we don’t tend like lawns but still habitually cut once or twice a year. There’s such a deep, wordless urge to cut down what has grown. Men who are loathe to sweep a floor will spend hours leveling a field by machine.

The “weeds” otherwise known as grasses, flowers, sedges, reeds, rushes, etc., have spent the spring and summer growing, flowering, feeding insects and birds, providing cover and food for animals of all sizes, exchanging energy with the soil, and producing seeds, and many of them are still doing so come fall. The men with their mowers are born into a culture that insists on cutting it all down. But much of that mowing, which is really an annual slaughter of a living community, is unnecessary.

As one fellow with a mower wrote in a short confessional essay,

So, as I wreak havoc on the flora and fauna in my fields twice a year, it feels selfish and probably is, doing this destructive work for the simple pleasure of doing work and preserving the view to satisfy some human aesthetic.

He wants to change, but hasn’t begun to tell a new story.

If we’re not cutting for hay or straw, to knock back harmful plants or invasives, or to control disease-carrying ticks near a home, why are we mowing fields? I’ve heard and read various answers: to keep the field from reverting to forest; to help build soil faster by mulching the vegetation; as a substitute for controlled burning; because it looks better.

But trees don’t sneak up on us, plants will always break down into soil, mowing provides few of the benefits that fire does, and (to my mind) in a burning world nothing looks better than healthy habitat.

Let’s back up a bit. It’s been a very rainy summer here in Maine, as I explored recently in my piece “Reimagining Rain.” Our vegetable garden has been a mess, in part because so much of the early summer sky was dark with clouds and rain. We’re surrounded here by tall pines, oaks, and maples, and we need all the summer light in the garden we can get. In the murk, the tomatoes didn’t know what to do, and the winter squash only found their motivation in August.

But the ungardened world has thrived, wildly. I don’t know if I’ve ever seen such thick, vibrant life in the fields and on the forest margins, where grasses, flowering plants, and shrubs have run beautifully amok. There’s a treasure trove of bright red winterberries in the marshes and roadside swamps, for example, and the milkweed has been thick and sturdy wherever I’ve looked.

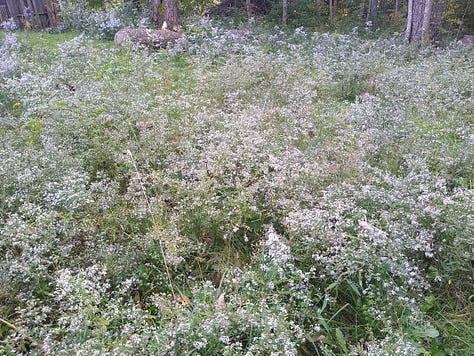

At home, though, it was the asters that blossomed into a dense galaxy. September into October, we were surrounded by blossoming white wood aster, blue wood aster, large-leaved wood-aster, and other asters at the edge of the woods, in the midst of the unmowed sections of lawn, along the barn, around the house, and even at our doorstep. The asters grew and thrived and flowered with a density and enthusiasm that Heather and I have never seen. We started calling our place Asterville.

And with the asters come the pollinators: bumblebees, honeybees, other bees, flies, wasps, beetles, moths, and butterflies, just to name the usual suspects. Through the summer, aster leaves feed more than a hundred native caterpillars around North America, and in the fall aster flowers are especially important because they, along with goldenrods, provide much of the autumn sustenance for insects preparing either to overwinter or migrate (like Monarchs). For three solid weeks, from dawn to dusk, the asters around the house were alive with insects gathering what they could before the cold knife of winter.

I couldn’t believe that the asters had so much to offer that they could sustain constant feeding for that amount of time. But then I did a little research and came up with some crazy math. (The botanists and ecologists among you are welcome to correct/supplement my info here.) What we think of as the aster flowers are actually made up of many small florets. Each New England aster flower head, for example, has 100-150 tiny florets, and each plant averages 50-100 flower heads (but could have many more). That’s a baseline of 5,000 to 15,000 florets per plant, each providing an abundance of nectar and pollen.

But for us this wasn’t just about the army of happy pollinators. Stepping outside the door into the buzzing community provided some much-needed joy, for one thing. And we feel good about hosting a sanctuary in a disrupted world.

Which brings me to the bigger picture. It’s a much bigger picture, one made up of a galaxy of actual stars.

Heather steps out every night before going to bed (at a reasonable hour) to look at the moon, sky, and stars. I often do the same, much later, in the midst of my wee hour writing and procrastinating. Looking up at the stars always makes me feel cold, literally – one of my little quirks – and the marvel of the vastness of visible space is for me always qualified by knowing that the only life among the stars that matters (and that we’re likely to experience) is right here at our feet.

Some endolithic bacterium on Mars or hydrothermal microbe on Enceladus will be interesting, but only an impoverished and haunting reflection of the lushness that surrounds us here. When we find scraps of life elsewhere, as I’m sure we will, the desperate facts of its existence should send us scurrying home to protect the pale blue dot that nurtured our species.

Waking, then, to hundreds or thousands of insects humming like the engine of life itself as they feed from flowers named for stars (“aster,” traced back through Latin to Greek, means “star”) is both a gift and a reminder of what’s vital and true.

In the push to reach Mars, I always wonder why we think we’re ready to launch off of this planet in search of life on others. My thought is that the modern industrial relationship to life here – both the living world and the billion or two of us who are impoverished and haunted – isn’t mature enough to seek it out anywhere else. I don’t mind spending the money and burning the resources to send some probes and drones – our own buzzing pollinators – but we don’t deserve to go anywhere until our own house is in order. Spending trillions to detect a virus on Europa while the Amazon burns is simply bad ethics. Things don’t have to be perfect before we venture outward, but they can’t be anything like the hot mess we’re making now.

In the Anthropocene, we live in a space between asters and disasters. (An ill-starred event is a dis-aster.) That Heather and I have been so amazed at the scale of insect activity on the asters is itself a measure of how deprived we all are of the former abundance of insects. It’s like pausing, eyes up, to marvel at a passing flock of a hundred geese, not conscious that it’s only been a handful of generations since flocks of passenger pigeons darkened the sky for hours at a time.

Likewise, admiring the roadside margins, cultivated gardens, and unmowed field edges where flowers and native shrubs shine with petal and fruit is a habit borne of ignoring the mowers that wipe clean the slate of existence wherever they travel. We identify the colorful survivors as abundance because we’ve grown up in a world where true abundance is rare and largely out of sight.

Nearly all of the fields where I post my nest boxes for tree swallows (and bluebirds, who need them less) are mowed each fall, converted from living communities of asters, goldenrods, milkweed, and much more into short, grassy deserts. If done early enough, it wipes out the Monarch chrysalises and caterpillars preparing for the next stage of a life far more complex than our own.

None of what is cut is collected to feed livestock. It’s merely cut and left to rot into soil along with the pollinators and rodents who didn’t escape the blades. There’s so much more happening in these habitats than we can easily see, like insects who overwinter in goldenrod galls and various plant stems. It’s painful to see it all wiped clean. Mowing like this is like winter coming before winter arrives, but we mistake the impoverished green growth that recovers in late fall for the loveliness of spring.

So, why mow? Why not mow less often, or not at all? I mean these not as rhetorical we-should-never-mow questions, but as actual questions we should ask to evaluate what’s necessary for us amid what’s best for the living world. Few of you own fields, I realize, but you can help improve biodiversity on public property, conserved land, or abandoned agricultural fields by encouraging better policy and management.

How best practice a new path? Personally, I like to start by mowing paths. Whether in a lawn converted to meadow, or in acres of field not in agricultural use, one solution I like is to mow the perimeter as often as necessary through the summer. It provides walking trails, allows you to see what’s happening in the wild fields, and it keeps young trees from creeping into open space. If you have a problem area with invasives, keep that mowed too.

If you don’t mind some other unsolicited advice… If you’re not managing the fields for any other reason, then manage them for habitat. Mow as late in the season as possible – around here, late November is much better than October – or in early spring. Better yet, based on your field’s particular needs, you can simply mow much less frequently, as in every two to five years. If the area is big enough, divide it into sections and mow them on different cycles to develop differential growth structure for habitat.

I’m having trouble finding a good comprehensive source of information on all this. There is so much more to the management of fields and meadows for biodiversity than I’ve even touched on here, and I’d like to offer a good source or two. But I’m only finding bits of advice here and there. If anyone knows of a good source, let me know.

I’ll close with a bit of poetry from Robert Frost, who knew all about human habits on the land. In this excerpt from his poem, “A Tuft of Flowers,” set in a hayfield mowed by hand with a scythe that morning, the poem’s speaker is visited by a bewildered butterfly who, upon searching, finds finally a stand of butterfly weed left by the man with the blade. The butterfly comes to him

Seeking with memories grown dim o’er night Some resting flower of yesterday’s delight. And once I marked his flight go round and round, As where some flower lay withering on the ground. And then he flew as far as eye could see, And then on tremulous wing came back to me. I thought of questions that have no reply, And would have turned to toss the grass to dry; But he turned first, and led my eye to look At a tall tuft of flowers beside a brook, A leaping tongue of bloom the scythe had spared Beside a reedy brook the scythe had bared. I left my place to know them by their name, Finding them butterfly weed when I came. The mower in the dew had loved them thus, By leaving them to flourish, not for us…

But we can do better than tufts and remnants. We don’t have a choice, actually. Life among the stars requires better practices and better stories.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

Something wondrous and strange: The Feral Atlas: The More-Than-Human Anthropocene. The Feral Atlas is an interactive and deeply fascinating exploration/illustration of the transformed Earth, one which I have only begun to explore. It’s a huge visual and verbal encyclopedia full of images, essays, analysis, and revelations. Please take a look and tell me what you think.

From the New Yorker, a long-form deep dive into the Great Cash-for-Carbon Hustle, the fraudulent carbon credit market that’s enriched the elite, created false optimism, perpetuated industrial pollution and fossil fuel use, and done very, very little to actually benefit life on Earth. To be clear, while the article focuses on one carbon credit brokerage, South Pole, it’s not just telling a story about a particularly egregious carbon credit scam. It’s meticulously deconstructing the whole market. As one former carbon credit CEO put it, “The big majority of what you see in the market, in my view, boils down to a lot of greenwashing, a lot of marketing, a lot of money-making.”

From Scientific American, an excellent op-ed about an important idea: the need to think about conservation on a much larger timescale. Too often conservation of an ecosystem or species is built around what we've studied in recent years or decades. But that timeframe is far too short to remember how that ecosystem or species existed for millennia before modern human disruption. We see the natural world through the clouded lens of "shifting baseline syndrome," in which a new, diminished normal is established each generation. Our ecological amnesia - what we've forgotten about the lush living world that once existed - makes it more likely that we won't understand enough about how to best rewild or resuscitate the natural world.

In related news, from All About Birds, an excellent article titled Battling a Green Glacier: How a Native Tree Became a Threat to Nebraska's Grasslands. It’s a case study of how, in a world that desperately needs its forests regenerated, a forest can be a negative for habitat and wildlife in a non-forested ecosystem. It's a key lesson for rewilding and reforestation: let deep knowledge of a habitat tell you what it needs to be.

From Grist, a bit of good news: The Supreme Court refused to hear conservative states' attempt to eliminate the Biden administration's use of the social cost of carbon. This metric, the social cost of carbon, is a vital tool in the quest to measure every government policy according to its impact on emissions that heat the atmosphere. We can expect the Biden administration to expand its use.

From Extinction Rebellion, their latest global newsletter highlights the organization’s huge range of activism across the planet: XR Global Newsletter #81: The World Is Collapsing.

From Vox, a good-news tale of what may be a hopeful trend worldwide: the return of Indigenous control to an increasing portion of their native lands. Within this context, the article tells the tale of the Winnemem Wintu tribe in the Shasta Cascade region of northern California, who recently purchased 1080 acres of their original territory. The trip will use grant funds to build a sustainable community for tribal members, and will continue their long battle to return salmon runs to the watershed corrupted and blocked by the Shasta Dam.

From the BBC, a related bad-news tale of how and why Australia just voted down a national referendum on Indigenous rights that would have, for the first time, amended its constitution “to recognise First Nations people and create a body for them to advise the government.”

From the Times, a concise op-ed from climate expert Zeke Hausfather explaining this year’s rapid increase in warming and its consequences, and offering a bit of cautious optimism about the road ahead.

From Inside Climate News, a reality check to dispel fears and misinformation about solar panels containing harmful substances and about concerns that their waste will be a problem for human health.

Also from Inside Climate News, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service has begun biobanking frozen tissue of endangered species, as a safeguard against extinction. It’s a sad but smart step as we strategize amid the Anthropocene crises.

Last year after seeing firsthand the harm mowing my pastures caused especially to ground nesting birds; I decided I would not mow this season. The resilience I witnessed was remarkable, with cover the meadowlarks, curlews, killdeer, Hungarian partridge, and sharp-tailed grouse all raised successful broods (some parents raised two broods). Just yesterday morning I was rewarded with the sight of two broods (about 26 birds) of Hungarian partridge scurrying across the gravel through the corrals and out into the tall grass. Reciprocity = Resilience.

Continuing to enjoy my travels through the archives - you asked in this lovely post whether anyone could recommend any resources regarding meadow management. I have two. One is a PNW-based meadow restoration outfit, but the general principles should apply in other northern corners of the US: Northwest Meadowscapes (https://northwestmeadowscapes.com). Plus their website is enchanting, and they mail out their seeds in little handmade envelopes, and they've even published a little softbound zine on meadow planting.

I also enjoy Benjamin Vogt's work - he is Midwest-focused but again, generally applicable principles. As a heads up, he does advocate using herbicides in certain cases, which I imagine he will eventually back away from, given how rapidly our understanding of the harm caused to pollinators by herbicides is advancing. His most recent book is Prairie Up.

I loved this post. I too experienced the full wonder of native asters this year due to our "spring of many atmospheric rivers." I've got three varieties in my mini-meadow, from a pale lavender to an almost plummy purple, which look glorious in the company of their goldenrod friends. It was a buzzing, glittering, zipping pollinator superhighway throughout the late summer and fall here. Such fun.