Life Is In The Air - redux

9/14/23 – Some thoughts on aeroecology

Hello everyone:

A few notes:

It’s been some time since I provided a link here to the indispensable analysis of

on the war in Ukraine. His latest, “The State of the War,” is concise, brilliant, and deeply humane. Perhaps one of these days I’ll follow through on my idea to write about the deep Anthropocene framework for the war, as daunting as that may be.I’m offering a (lightly edited) redux of a favorite 2022 essay this week because, for the first time in two and a half years, my nights of wee-hour work to produce a new essay for you simply weren’t enough to pull it together. I’ve been wrestling with a hard topic – the Anthropocene as a consequence of a parasitic industrial culture, while also talking about the ubiquity of parasites in the community of life – and just couldn’t carry it across the finish line. I may abandon it or try again for next week.

But about next week… Hurricane Lee will give Maine a hard glancing blow this weekend, and we may lose power for a while. The trees still carry all their leaves, and their roots have been sitting in wet ground for months now. It’s a good recipe for downed trees and the cutting off of power. Heather and I will be out of the state during all the fun, and may come back to a dark house.

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read some more curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

One of a thousand writerly gems in Helen Macdonald’s brilliant Vesper Flights, her collection of personal natural history essays, is this line: “Science reveals to us a planet that is beautifully and insistently not human.” Her observation echoes lines by Virginia Woolf about the sky’s cold beauty: “Divinely beautiful it is also divinely heartless… If we were all laid prone, stiff, still the sky would be experimenting with its blues and golds.”

This is a truth I dearly wish we all kept in mind: We do not give this planet its meaning.

Even in the Anthropocene, as the threat of extinctions increases in parallel with the growth of our population and consumption, wonders far greater than us are everywhere, from sequoias, canyons, and hurricanes to the intricate lacework of diatoms and fungal mycelia. We’re woven into an exquisite fabric of life, and our love for life on Earth should motivate us to do the hard work that’s necessary to revitalize it. We’re on the right path if we recognize that each species and ecological relationship and habitat is a pixel in a vast portrait, drawn for us by scientific curiosity and investigation, of a planet gloriously rich with complex existence.

To be clear, science is only revealing this meaning, not creating it. And it has only begun.

This not-human, intelligent profusion of biology should remind us that the Anthropocene is a mark of failure, not success. We’re not at the top of the tree of life; we’re an odd ape devouring its fruit even as we saw off the branches that support us.

One consequence of the indoor existence of industrial civilization is that we’ve forgotten how to live in the real world. At the same time, we’ve made survival for the rest of life increasingly difficult. Science can help us see the losses and disruptions because it is a form of collective knowledge gathered and refined over time.

But science, like Indigenous knowledge, is competing in a loud marketplace of ideas. Our individual ways of knowing are now mostly rooted in the economies which have displaced the ecologies that birthed and sustained us. They cradle us still, though we scarcely notice. We've become creatures of capital and debt, not realizing that we’re still animals of field and stream. Unlike Indigenous peoples, we’re not often raised to think about our humble place in the profusion.

So let’s talk briefly about the profusion.

Here on the surface of the Earth, wherever we open our eyes and aim our own curiosity, life is still astonishing and abundant, if diminished and declining. Plants build entire worlds out of light and water, animals host multitudes of microbes within and around them as they walk, hop, or slither the continents, and insects fill the spaces between like bubbles in a fountain.

Meanwhile, beneath our feet and below the waves the seas and soil teem. The population of living microbes in a spoonful of soil is greater than the entire human population; a pinch can contain a million cells, ten thousand species, and miles of fungal filaments. Life originated in the oceans and will persist there regardless of our efforts to the contrary. As you read this there are innumerable species, great and small, thriving in the black depths as they have for millions of years.

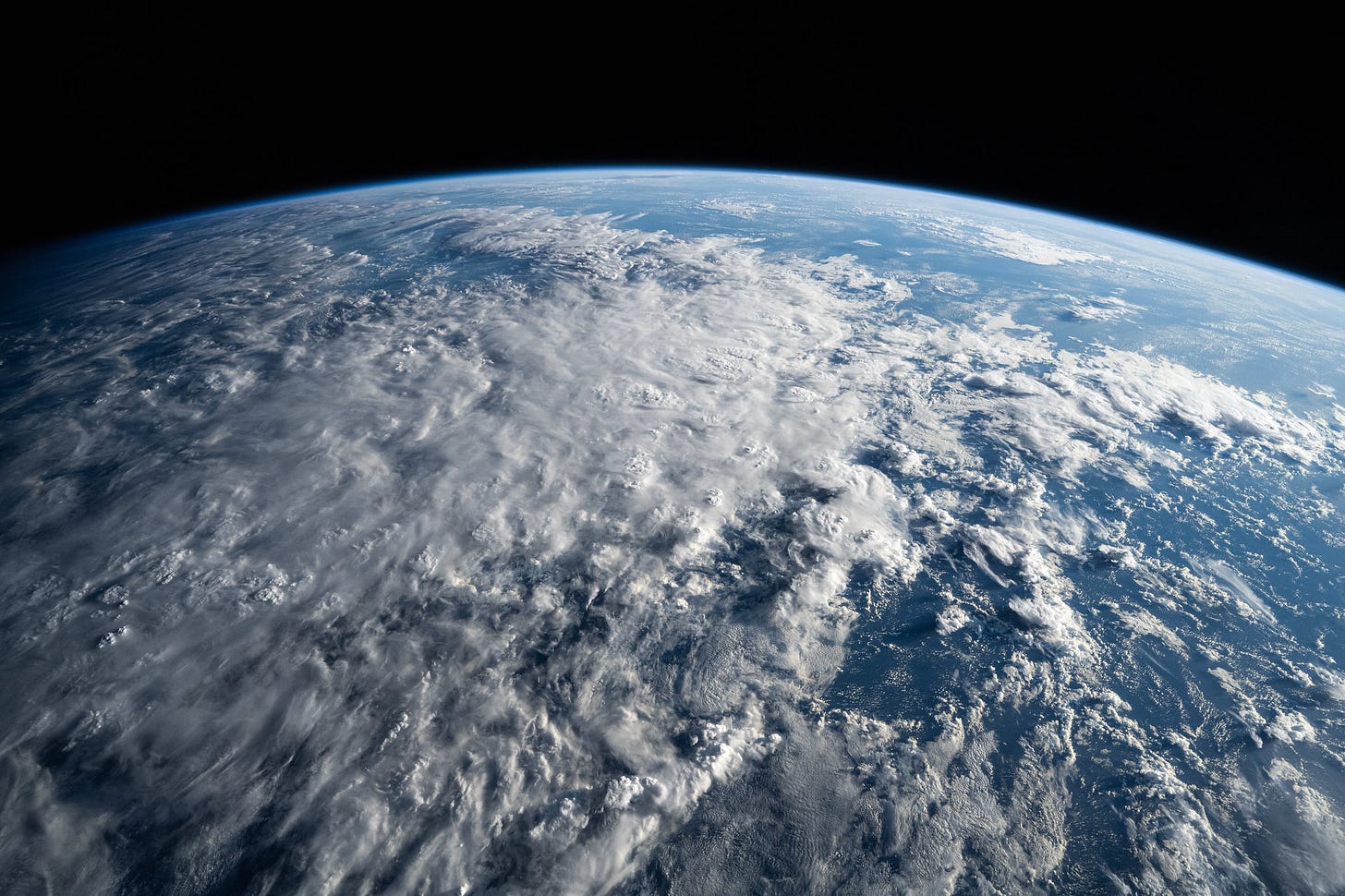

Nothing that our remarkable off-planet scientific observations have revealed suggests with any certainty that such a profusion of life exists elsewhere. Certainly the odds favor the existence of life dotted through the galaxies, but we will know nothing but telescopic hints of it before the decisions we’re making now either preserve or decimate our own rich community of species. Desolation or restoration are the only choices here, and dreamy visions of colonizing green exoplanets are absurd, irrelevant, and costly distractions.

But what about the air above us? The sky may start at our feet, but it has inhabitants for whom the air is a medium of existence rather than a mere extension of terrestrial space or a metaphor for freedom. Ecology, I’d always thought, was only a terrestrial and aquatic science. But I was wrong. In Vesper Flights, I learned for the first time that airspace is habitat. In short, I learned about aeroecology.

Aeroecology is a fairly new discipline. It is the study of airborne organisms – birds, bats, arthropods, and microbes – which thrive in the lower atmosphere. They depend upon it. We think of the air as merely a space for transport, as if the migrations of birds and the wind-borne journeys of young spiders across continents were little more than the arc of a thrown stone. But this is life thriving on the wing. The airborne travel, sure, but they also feed, sleep, socialize, and colonize by mastering the transparent habitat above us poor earth-bound animals. They sustain us, too, in myriad ways, not least the untold numbers of airborne bacteria which provide nuclei for raindrops and snow crystals to form on before dropping.

One of my first lessons regarding the mysteries of airborne life came years ago when in the course of my Antarctic reading and writing I learned a little about the microbes that fall with the snowflakes even in the highest reaches of the ice caps around the South Pole. Descending from the jet stream, these microorganisms become buried but do not always die. Bacterial samples millions of years old have been extracted from deep in the ice and revived in a lab. (Likewise, scientists have revived 100 million-year-old bacteria found in sediment cores below the deep ocean floor.) This is life spreading and persisting on a timescale beyond our comprehension.

And yet these microbes have the capacity to live in the moment too, reviving briefly from a frozen state on the surface of the snow if they happen to be in the liquid margin of an ice crystal faintly warmed by the sun on a –30°F day. Picture, then, a planet where the tiniest life forms travel the winds and find a home even in the harshest environments, and even if they have to wait millions of years for conditions to improve. What is the intelligence and durability of humans compared to that?

Aeroecology works necessarily at the boundary between earth and atmospheric sciences, and incorporates the disciplines of ecology, geography, computer science, computational and conservation biology, and engineering. It has its origins in the “ghosts” of migrating flocks seen by bewildered radar operators after WWII. Now you and I can follow the progress of migrating birds as they move at night across the network of finely-tuned North American weather radar systems. The best place to do this is BirdCast, which not only observes but predicts, like a weather forecast, the migration intensity for the days ahead. For example, tonight - September 14th, 2023 – 319 million birds are expected to be drawn like magnets along their high and ancient paths. (You can use BirdCast to get specific too. Above Maine, for example, more than 8 million birds are in motion as I publish this, and BirdCast provides information on altitude, direction and speed, and the list of species likely to be passing overhead. It’s a beautiful display of aeroecological science in action.)

Aeroecologists use these remote-sensing tools to help map and model the distribution of airborne species and their relationships to the wide range of habitats over which they travel. Managing and protecting birds and bats grows increasingly difficult as those habitats diminish in size and quality. But the research also points to how these species can recover when we protect and enlarge the earthbound ecosystems they depend on.

And perhaps the most important thing I can talk about here, beyond the sheer marvel of life in the air – more on that in a moment – is that dependency. I’m thinking less about the durable microbes here, though there’s no doubt that the Anthropocene at the microbial level has been transformational. (I wrote about this in a pair of essays titled The Microbial Anthropocene.) I’m thinking a bit more about the spiders and insects – wasps, aphids, beetles, moths, and even migratory dragonflies – billions of which fly over us, unseen except by the newest generation of radar which can, according to Macdonald, “detect a single bumblebee over thirty miles away.”

But I’m mostly thinking of the birds who thread together the continents, shifting thousands of miles in the spring to mate and rear young and shifting again in autumn to warmer wintering grounds. It’s easy to forget sometimes that “our” bobolinks or hermit thrushes here in North America are equally South American inhabitants. It’s hard, though, in this era, to imagine keeping them safe along that entire route, year after hotter year.

Migrations are always perilous odysseys, but the journeys have for the last century or two been increasingly fraught. New perils – lit towns and cities, skyscrapers, radio and TV towers, wind turbines – stand in the path, while ecological absences await them in their time-honored stopovers. In New York City alone, an estimated hundred thousand birds or more die every year because of light pollution and window collisions. In the countryside, most of the marshes and meadows are gone, much of the swamps and old growth forests are gone. Fields and family farms that dotted the Earth’s landscape could be avoided or visited, but pesticide- and herbicide-soaked industrial-scale agriculture is in some flyways a poisoned minefield with few alternatives. The air itself is polluted with aircraft and their burnt fuel, soot, chemical contaminants, wildfire smoke, antibiotic-laced dust from massive cattle feedlots, and even PFAS-infused rain.

With these changes came changes in navigational cues, food and water sources, nesting and roosting habitats, and reductions in the population and distribution of species the migrators rely on. In turn, whatever impact the altered Earth has on the birds becomes an impact the altered flocks have on the Earth. Change and diminishment will create more change and diminishment until the cycle is broken by our decision to make our presence on the Earth healthier. And much has been done to protect major migratory stopover points around the world. The birds tell us what they need wherever they choose to land and feed and drink. We just need to keep listening.

The warming climate, which as I’ve often noted is merely one feature of our larger threat to life on Earth, is another matter. Weather gets stranger and stronger, food and water become less predictable, seasons fluctuate in new ways, and heat turns even the sky into a desert and the forests below into pest- and fire-prone war zones.

“The carbon we burned to make us indifferent to the weather,” Nicie Panetta wrote in one of her excellent Frugal Chariot reviews, “is now making us infinitely more vulnerable to it.” Birds and other residents of the skies are even more vulnerable. The sky is the metaphorical coal mine, and the millions of migratory birds are all canaries. If we continue to close the real coal mines, maybe hermit thrushes, broad-winged hawks, black-billed cuckoos, bobolinks, chestnut-sided warblers, and all the hundreds of millions of nighttime companions will flash across the moon above and radar screens below on their way to a world of safe harbors, season after season and year after year.

An argument could be made that the full rewilding of migratory pathways and the habitats that sustain them is one good path out of the Anthropocene. If we care for the birds who stitch the world together, maybe we’ll stitch the world together.

I would be remiss if I didn’t close with the miracle of swifts, perhaps the most aeroecological species on the planet. That is, swifts live most of their lives in the air. Macdonald calls them “the closest thing to aliens on Earth.” A young European swift, when it drops out of the nest to make its first flight, will not touch tree or ground for two or three years. They feed and drink on the wing, bathe in the rain, and sleep with both eyes closed at high altitude. When old enough to mate, they collect nest materials on the wing too. Even adult swifts who are duty-bound to the nest are part of our world for only three months a year.

Even then, though, birds not sitting on the nest will rise in a flock twice a night, just after sunset and just before sunrise, up to eight thousand feet: their vesper flights. The title essay from Vesper Flights is full of Macdonald’s poetic language – she can really make her nonfiction sing – in part because she has been intrigued by swifts her entire life. You can hear that in her explanation of why they’re up at eight thousand feet. At that height, she says,

they can see the scattered patterns of the stars overhead, and at the same time they can calibrate their magnetic compasses, getting their bearings according to the light polarisation patterns that are strongest and clearest in twilit skies. Stars, wind, polarised light, magnetic cues, the distant rubble of clouds a hundred miles out, clear cold air, and below them the hush of a world tilting toward sleep or waking towards dawn. What they are doing is flying so high they can work out exactly where they are, to know what they should do next. They’re quietly, perfectly, orienting themselves.

As should we.

We could do no better than John Stimpson, retired Weetabix salesman in the U.K., who at the age of 80 has built 30,000 nest boxes for swifts (and 1500 for other birds): “I get so much pleasure from wildlife,” he says. “Building these boxes is one way I can pay it back.”

Imagine if we each did as much - or half as much - for the living world. How much good could we do? The sky’s the limit.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

The March to End Fossil Fuels is this Sunday in NYC. Join the crowd!

From Mother Jones, an interview with Ben Goldfarb, author of the new book Crossings: How Road Ecology is Shaping the Future of Our Planet. Those of you who have been with me long enough remember a three-part series I did on road ecology. As Goldfarb notes, our habit of driving ourselves around does more damage to natural systems than just about anything else we do.

From Grist, an important study finds that cutting in half the human consumption of beef, chicken, pork, and milk could “effectively halt the ecological destruction associated with farming.

From Yale e360, why fireflies are disappearing and why it’s not too hard to save them.

Remember to check out BirdCast, the live and predictive radar tool for observing migrating birds over the U.S. They’re very much on the move already. On the landing page, you can either type in your state for a wealth of local migration data, or click on the forecast map of the U.S. for the big picture. Well worth a few minutes of your time if you want a reminder of the wondrous ancient dance happening overhead.

From the Times, a great interactive piece on the odyssey of migratory birds who are flying south through the radically diminished American landscape. The article’s excellent maps are worth your attention, but I highly recommend reading the full article for the comprehensive analysis and the emphasis on solutions to protect what remains of these astonishing avian populations.

From Nautilus, an excellent interview with an expert in the study of existential risk. He offers several insights worth reading, but I’m especially glad to see his emphasis on the importance of strengthening democracy. Resilient politics make resilient policy.

From Inside Climate News, a lonely quest by a Pennsylvania senator to get fracking waste listed as a hazardous substance.

Also from Inside Climate News, a breakthrough in ocean CO2 capture. Unlike the hyped boondoggle that direct air capture seems to be, ocean capture may prove to be effective and essential. There’s no discussion in this article of how the CO2 will be sequestered, since it’s focused on the capture technology, but the benefits of ocean capture include 1) higher concentrations of CO2 in water vs. air, 2) reduction of acidification in seawater, and 3) indirect reduction of atmospheric CO2 because so much of it is absorbed by the oceans anyway.

From the Times, the Biden administration has prohibited drilling in more than half the National Petroleum Reserve in Alaska, and canceled oil and gas leases in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (created by the Trump administration). These are both huge wins for rational energy and climate policy, but they are both shadowed by the administration’s approval of the Willow project, a carbon bomb the planet cannot afford.

From Phys.org, a study finds that beaver activity in the Arctic is increasing the release of methane. Beavers are moving north into the tundra as the world warms. It’s unclear still if the increase in methane is a short-term phenomenon or one that will act as a significant feedback source for Arctic warming.

"Haru no umi hinemosu notari notari kana". --Buson

Beautiful writing. This essay is rewarding at many levels. Getting an essay across the finish line can be so difficult. Some write themselves in great looping swoops of inspiration, rather like a swift. Others are ground pounders fighting their way through thickets.

Be careful with this storm coming, it's the gift of climate change and such storms may become the norm for you in the East, just like giga-fires and drought seem to be our coming new normal out here in the west. Microbes can weather all of this as you demonstrate, and their roots are deep. We tetrapods are the exotic outgrowths of that base and exposed to the climate winds that blow. So we rise and fall like that famous haiku says, yes we rise and fall.