Hello everyone:

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read some curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

I wrote last week in my post on aeroecology that I’ve been meaning to write about the microbial Anthropocene for some time, but because of the vastness of the topic didn’t know where to start. Often, though, a writer just needs to start, with or without a map, and see where the path leads. My goal here is only to roughly map the scale and depth of our often invisible transformation of the microbial world. It’s a topic worthy of several shelves in a library, not just an exploratory essay. I’ll try to point you toward that library.

The phrase “microbial Anthropocene” is a mouthful, so I’ll start with some basics. (This is helpful for me too. As with many of my topics, I’m learning as I go.) “Microbe” means “small life.” It’s a very general term, like “plant” or “animal,” and simply refers to life forms too small to see with the naked eye. That’s the micro in microbiology (the study of microbes), microscope (necessary to study them), and in microorganism (a synonym). The main categories here are bacteria, fungi, archaea, protists, and viruses.

The problem with emphasizing size, though, is that there are notable exceptions. Lots of fungi, of course, are very visible – popping up as mushrooms, turning bread green, or occasionally growing to become one of the largest life forms on Earth – and it seems strange to lump them in with a virus thousands of times smaller than the width of a human hair. And there are other complexities in defining microbes, not least that viruses are arguably not alive in the way other microorganisms are. And as I mentioned last week in other not-quite-dead news, some bacteria can comfortably lie dormant for 100 million years or more. Archaea, meanwhile, resemble bacteria but share some features of multicellular organisms. In short, then, microbes are astonishingly varied and increasingly hard (as we learn more) to define.

But we don’t need to split hairs for my purposes here, so just know that, generally speaking, microbes are single-celled life forms. (For the microbiologists among my readers – you know who you are – be nice to me. I’m on a mission.)

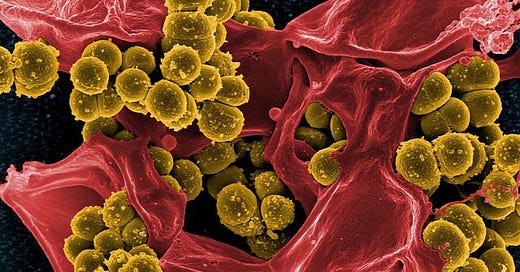

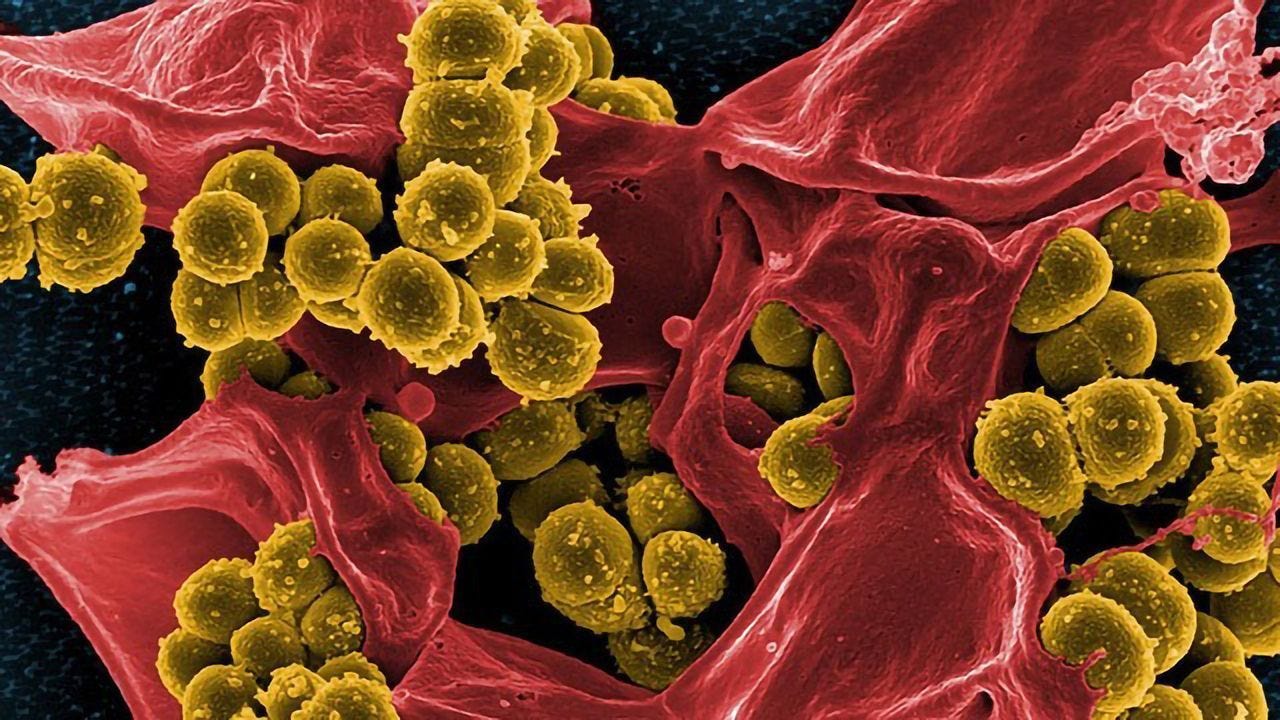

Earth is their planet, not ours. The great E.O. Wilson famously described insects as “the little things that run the world,” but I think that insects would agree that they’re one level down from the real bosses. These littler things that really pull the planet’s strings are 1) far more numerous and varied than we have grasped (one estimate suggests we’ve identified 0.001% of an estimated trillion microbial species), 2) responsible for the processes that regulate the entire living world, and 3) infused into the lives and bodies of every other living being. In the human body, for example, there are more microbial cells (about 39 trillion) than human ones (30 trillion).

Microbes are not merely pervasive, ubiquitous, and enduring; they are fundamental to every aspect of life on Earth. Thus, when we transform the little things that run the world, we transform the world.

Bdellovibrio, a predatory bacteria and merely one of the approximately trillion species of microbes, might be the planet’s fastest living creature. When hunting other bacteria, it can move about 600 times its body length in a second. (A cheetah, for comparison, accelerates to about 16 body lengths per second.) I learned this from a cute, layman-friendly introduction to microbes created by the American Museum of Natural History. The AMNH site also notes that the great paleontologist and essayist Steven Jay Gould once said that “we should forget about the Age of Dinosaurs, forget about the Age of Man—we’ve always lived in the Age of Bacteria.” (This is one more reason to suggest that naming the current era the Anthropocene is an act of hubris. But hubris is how we got here, so maybe it’s appropriate.)

Microbes were the first life to evolve and will be the last life standing, no matter what happens to the Earth. They drive the biogeochemical cycles (carbon and nitrogen especially) that control conditions for life on the planet. At least half of Earth’s oxygen is produced by photosynthesizing bacteria in the oceans. And perhaps more importantly, microbes (specifically yeasts) make all of our bread, beer, and cheese… Not to mention wine, vinegar, yogurt, miso, tofu, and about 3500 other fermented foods cultured by people around the world.

Many microorganisms are so hardy that if they hitched a ride to Mars, where billionaire dreams will soon go to die, they have a chance of surviving. There are plenty of bacteria here, for example, that live only on sulfur products. Provide them a little nitrogen and trace amounts of water and they might be happy Martian colonists for a while.

One of the primary capacities of microbes that have made them successful is their astonishing ability to pass on genetic material “horizontally” between individuals of a species and, more importantly, individuals of different species. Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) is a rapid evolutionary workaround that avoids the time necessary to pass on DNA from generation to generation until mutations arise that improve the species. (This happens in a variety of ways, which I won’t get into here, but if you want to dive in you could start with this simple but clear video and then try parsing a very thorough Wikipedia page.) The genes acquired through HGT, if useful, are then passed on as DNA or via HGT to another microbe.

I mention HGT because it’s the common strategy by which microbes acquire antibiotic and vaccine resistance, learn to degrade man-made chemicals like pesticides and petroleum pollutants, pass on traits that increase their virulence amid dense human populations, and respond to the impacts of a changing climate.

Watch the video here as bacteria evolve in just a few days to thrive on exponentially increasing amounts of antibiotics. Note, though, that in this giant Petri dish as in rivers and sewer systems around the world we’re not creating these antibiotic-resistant bacteria. We’re selecting for them by creating a world in which they can thrive.

We are, though a combination of ignorance and arrogance, driving microbial evolution. Given the fundamental importance of microbes, this means that we’re changing the foundations of the natural world. Our Anthropocene journey isn’t a journey across space. It’s an acceleration of time, the time it takes to create an unfamiliar planet. Evolution in the Anthropocene isn’t the slow Darwinian fluctuation in the size of finches’ beaks; it’s more like the bacteria in the video above.

We’re burning the maps of our path back to the norms of the Earth that nurtured us. The farther we travel while emitting greenhouse gases, erasing ecosystems, overexploiting animals and plants that need to live their own lives, and spreading toxic chemistry across the globe, the more of the map we burn and the harder it will be to return living conditions on the planet to anything resembling home.

Here’s a calmer way to say all of that, from a 2014 scientific paper called Microbiology of the Anthropocene. Note, though, that the language hides a level of concern that I’m guessing is not much different than my own. “Directional natural selection” is another way of describing our intense narrowing of microbial life’s options. Alterations of the carbon and nitrogen cycles is the equivalent of messing with the life support systems on a spaceship. And “selection for altered pH and temperature tolerance” is a polite way of describing the tragedies of an acidifying ocean and a hotter atmosphere, both of which have been key components of Earth’s previous mass extinction events.

As the Anthropocene unfolds, environmental instability will trigger episodes of directional natural selection in microbial populations, adding to contemporary effects that already include changes to the human microbiome; intense selection for antimicrobial resistance; alterations to microbial carbon and nitrogen cycles; accelerated dispersal of microorganisms and disease agents; and selection for altered pH and temperature tolerance. Microbial evolution is currently keeping pace with the environmental changes wrought by humanity.

And here’s a graphic from that paper:

There’s a lot to unpack here, but in brief the authors selected a half dozen categories of Anthropocene impacts (listed down the left side) and mapped the growth of those impacts through human history (from left to right). They’ve chosen the dawn of the industrial revolution as a starting point for the Anthropocene, but have noted two other candidates for that starting point: the beginning of large-scale agriculture and our overhunting of tasty megafauna about 10,000 years ago (which they cleverly call the Paleoanthropocene), and the Great Acceleration in the twentieth century when our population and impacts radically intensified. You’ll see in the image that when we reached the Great Acceleration the impacts multiplied and worsened.

The logarithmic scale here is important enough that your jaw should be at least a little closer to the floor. Like the antibiotic resistance video above, this is a portrait of exponential growth, in this case with each time interval at the bottom of the image ten times shorter than the interval before it.

If, as seems obvious, most of our shift in microbiological evolution and planetary dynamics has occurred in just the last century – a time span scarcely measurable in Earth history – then we are playing God with this planet less like an omniscient overseer and more like a drunk driver going the wrong way on a highway full of school buses. We are in no way equipped to be deities, particularly to the far more adapted microbes.

We are more accurately described by numerous Native American traditions that depict humans as a younger sibling to the species around us. Those traditions understand that plants and animals have been here far longer than we have, and so already know how to live, whereas because of our particular type of consciousness, we’re still learning. Or we were still learning, until our invention of lunatic capitalist industrialism convinced us we could drive anywhere we wanted.

So next week I’ll look, briefly, at some of what has been learned about the ways we’re reshaping the microbiological world. I’m thinking of these impacts as falling into three categories: Extinctions within Extinctions, Unnatural Selection, and Making Trouble. Stay tuned to see what all that means…

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

From the Times, I missed some important good news in the climate/energy portions of the Inflation Reduction Act. Remember that terrible Supreme Court decision reducing the EPA’s power to regulate greenhouse gases as pollution? The court said that Congress must make the EPA’s power explicit, and now it has, through language slipped into the IRA. CO2 produced by the burning of fossil fuels is now a pollutant the agency is empowered to regulate.

From Hakai, two fascinating articles on indigenous sea gardens and forest gardens. Colonization of North America brought a winner-take-all ignorance which swept aside better techniques for creating highly productive food sources. They were better because they didn’t rely on the overexploitation of resources that has, among other mistakes, led us inexorably to the Anthropocene.

From Yale e360, a short film (8 minutes) called The Three Cricketeers, about a family on a mission to fight climate change and the harms of industrial agriculture by turning crickets into popular food. They sell treats (chocolate-covered crickets, of course) and cricket flour so that you can make your own.

The always-great Bill McKibben has an excellent new Crucial Years post, this one about the strange new ways water moves, or doesn’t, through the atmosphere of a rapidly-warming Earth. “We live on a different planet than we used to,” he says, and while the impacts from floods and droughts that are haunting communities across the planet can partially be chalked up to bad governance, colonialism, inertia, and greed, the greater reality is physics: “Warm air holds more water vapor than cold, and from that the main events of post-modern twenty first century will descend.” Read it, and subscribe to his newsletter if you want a good weekly letter on the fight for climate sanity.

To illustrate McKibben’s point, from the Times we have an assessment of the debilitating heat, drought, and floods in China this summer. Whole cities have been forced to reduce electricity usage because too little hydropower is available from the nation’s dams.

Another amazing letter, thank you. I love this line: 'We’re burning the maps of our path back to the norms of the Earth that nurtured us.'

I so look forward to receiving your newsletter. It makes me like my inbox more. I hope people feel the same way about my substack.

Looking forward to learning more and microbes!