Life Is In The Air

8/18/22 – Some thoughts on aeroecology

Hello everyone:

The imperfect but still impressive Inflation Reduction Act was just signed into law by President Biden; here is a good but brief analysis of the pros and cons of its massive climate and energy initiatives from Mother Jones.

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read some more curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

One of a thousand writerly gems in Helen Macdonald’s brilliant Vesper Flights, her collection of personal natural history essays, is this line: “Science reveals to us a planet that is beautifully and insistently not human.” Her observation echoes lines by Virginia Woolf about the sky’s cold beauty: “Divinely beautiful it is also divinely heartless… If we were all laid prone, stiff, still the sky would be experimenting with its blues and golds.” This is a truth I dearly wish we all kept in mind: we do not give this planet its meaning.

Even in the Anthropocene, as the threat of extinctions increases in parallel with our population growth and global temperatures, wonders greater than us are everywhere. We’re woven into an exquisite fabric of life. Our best hope now is to do the hard work that comes from a recognition that each species and ecological relationship and habitat is a pixel in a vast portrait, drawn for us by scientific curiosity and investigation, of a planet gloriously rich with complex existence. To be clear, science is only revealing this meaning, not creating it. And it has only begun.

This not-human, intelligent profusion of biology should remind us that the Anthropocene is a mark of failure, not success. We’re not at the top of the tree of life; we’re devouring its fruit even as we saw off the branches that support us.

The trade-off for the indoor existence of industrial civilization is that we’ve forgotten how to live in the real world, and in doing so made survival increasingly difficult for life in general. Science can bridge the gap because it is a form of collective knowledge, and we all make use of its findings to one degree or another.

But our individual ways of knowing are now mostly rooted in the economies which have displaced the ecologies that birthed and sustained us, and which cradle us still. We're creatures of capital and debt, not animals of field and stream. Unlike Indigenous peoples, we’re not often raised to think about our humble place in the profusion.

So let’s talk briefly about the profusion.

Here on the surface of the Earth, wherever we open our eyes and aim our own curiosity, life is still astonishing and abundant, if diminished and declining. Plants build entire worlds out of light and water, animals host multitudes of microbes within and around them as they walk, hop, or slither the continents, and insects fill the spaces between like bubbles in a fountain.

Meanwhile, beneath our feet and below the waves the seas and soil teem. The population of living microbes in a spoonful of soil is greater than the human population; a pinch can contain a million cells, ten thousand species, and miles of fungal filaments. Life originated in the oceans and will persist there regardless of our efforts to the contrary. As you read this there are innumerable species, great and small, thriving in the black depths as they have for millions of years.

Nothing that our remarkable off-planet scientific observations have revealed suggests with any certainty that such a profusion of life exists elsewhere. Certainly the odds favor the existence of life dotted through the galaxies, but we will know nothing but telescopic hints of it before the decisions we’re making now either preserve or decimate our rich community of species. Desolation or restoration are the only choices here, and dreamy visions of colonizing green exoplanets are absurd, irrelevant, and costly distractions.

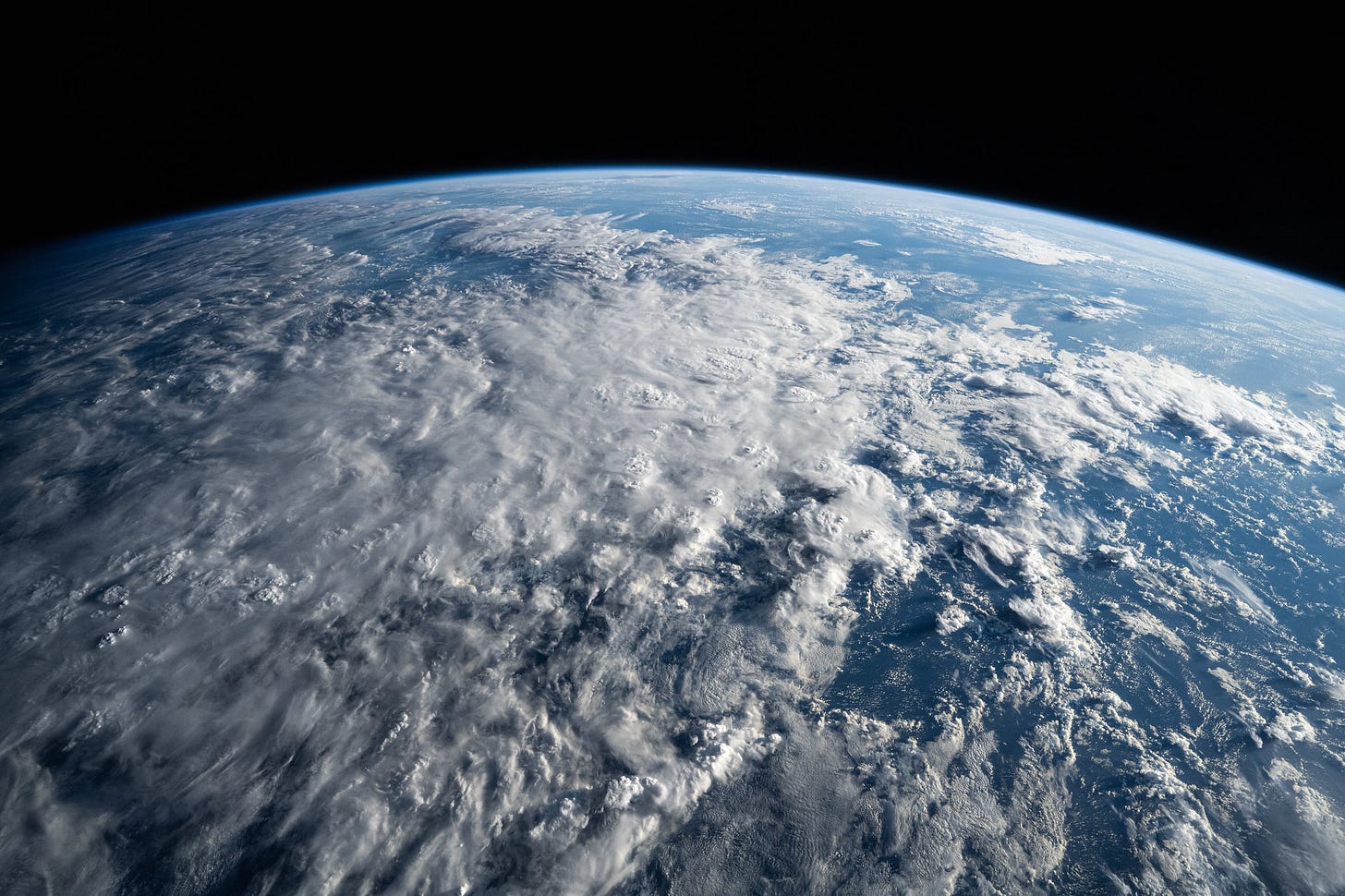

But what about the air above us? The sky may start at our feet, but it has inhabitants for whom the air is a medium of existence rather than a mere extension of terrestrial space or a metaphor for freedom. Ecology, I’d always thought, was only a terrestrial and aquatic science. But I was wrong. In Vesper Flights, I learned for the first time that airspace is habitat. In short, I learned about aeroecology.

Aeroecology is a fairly new discipline. It is the study of airborne organisms – birds, bats, arthropods, and microbes – which thrive in the lower atmosphere. They depend upon it. We think of the air as merely a space for transport, as if the migrations of birds and the windborne journeys of young spiders across continents were little more than the arc of a thrown stone. But this is life thriving on the wing. The airborne travel, sure, but they also feed, sleep, socialize, and colonize by mastering the transparent habitat above us poor earth-bound animals. They sustain us, too, in myriad ways, not least the untold numbers of airborne bacteria which provide a core for rain and snow to form on before dropping.

One of my first lessons regarding the mysteries of airborne life came years ago when in the course of my Antarctic reading and writing I learned a little about the microbes that arrive with the snow even in the highest reaches of the ice caps around the South Pole. Descending from the jet stream, these microorganisms become buried but do not always die. Bacterial samples millions of years old have been extracted from deep in the ice and revived in a lab. (Likewise, scientists have revived 100 million-year-old bacteria found in sediment cores below the deep ocean floor.) This is life spreading and persisting on a timescale beyond our comprehension.

And yet these microbes have the capacity to live in the moment too, reviving briefly from a frozen state on the surface of the snow if they happen to be in the liquid margin of an ice crystal faintly warmed by the sun on a –30°F day. Picture, then, a planet where the tiniest life forms travel the winds and find a home even in the harshest environments, and even if they have to wait millions of years for conditions to improve. What is the intelligence and durability of humans compared to that?

Aeroecology works necessarily at the boundary between earth and atmospheric sciences, and incorporates the disciplines of ecology, geography, computer science, computational and conservation biology, and engineering. It has its origins in the “ghosts” of migrating flocks seen by bewildered radar operators after WWII. Now you and I can follow the progress of migrating birds as they move at night across the network of finely-tuned North American weather radar systems. The best place to do this is BirdCast, which not only observes but predicts, like a weather forecast, the migration intensity for the days ahead. For example, on August 18th – my birthday, and the day this essay comes out – 152 million birds are expected to be drawn like magnets along their high and ancient paths.

Aeroecologists use these remote-sensing tools to help map and model the distribution of airborne species and their relationships to the wide range of habitats over which they travel. Managing and protecting birds and bats grows increasingly difficult as those habitats diminish in size and quality. But the research also points to how these species can recover when we protect and enlarge the earthbound ecosystems they depend on.

And perhaps the most important thing I can talk about here, beyond the sheer marvel of life in the air – more on that in a moment – is that dependency. I’m thinking less about the durable microbes here, though there’s no doubt that the Anthropocene at the microbial level has been transformational. (I plan on writing about this someday, though it’s hard to know where to start.) I’m thinking a bit more about the spiders and insects – wasps, aphids, beetles, moths, and even migratory dragonflies – billions of which fly over us, unseen except by the newest generation of radar which can, according to Macdonald, “detect a single bumblebee over thirty miles away.”

But I’m thinking mostly of the birds who thread together the Americas, for instance, shifting thousands of miles in the spring to mate and rear young and shifting again in autumn to warmer wintering grounds. It’s hard to imagine sometimes that “our” bobolinks or hermit thrushes are also South American inhabitants. It’s even harder, in this era, to imagine keeping them safe along that entire route, year after hotter year.

Migrations are always odysseys, but the journeys have for the last century or two been increasingly perilous. New perils – lit towns and cities, skyscrapers, radio and TV towers, wind turbines – stand in the path, while ecological absences await them in their time-honored stopovers. In New York City alone, an estimated hundred thousand birds or more die every year because of light pollution and window collisions. In the countryside, the marshes and meadows are gone, the swamps and old growth forests are gone. Fields and family farms that dotted the Earth’s landscape could be avoided or visited, but pesticide- and herbicide-soaked industrial agriculture is in some flyways a poisoned minefield with few alternatives. The air itself is polluted with aircraft and their burnt fuel, soot, chemical contaminants, wildfire smoke, antibiotic-laced dust from massive cattle feedlots, and even PFAS-infused rain.

With these changes came changes in navigational cues, food and water sources, nesting and roosting habitats, and reductions in the population and distribution of species the migrators rely on. In turn, whatever impact the altered Earth has on the birds becomes an impact the altered flocks have on the Earth. Change and diminishment will create more change and diminishment until the cycle is broken by our decision to make our presence on the Earth healthier. And much has been done to protect major migratory stopover points around the world. The birds tell us what they need wherever they choose to land and feed and drink. We just need to keep listening.

The warming climate, which as I’ve often noted is merely one feature of our larger threat to life on Earth, is another matter. Weather gets stranger and stronger, food and water become less predictable, seasons fluctuate in new ways, and heat turns even the sky into a desert and the forests below into pest- and fire-prone war zones.

“The carbon we burned to make us indifferent to the weather,” Nicie Panetta wrote last week in another of her excellent Frugal Chariot reviews, is now making us infinitely more vulnerable to it.” Birds and other residents of the skies are even more vulnerable. The sky is the metaphorical coal mine, and the millions of migratory birds are all canaries. If we continue to close the real coal mines, maybe hermit thrushes, broad-winged hawks, black-billed cuckoos, bobolinks, chestnut-sided warblers, and all the hundreds of millions of nighttime companions will flash across the moon above and radar screens below on their way to a world of safe harbors, season after season and year after year. An argument could be made for the full rewilding of migratory pathways as a path out of the Anthropocene. If we care for the birds who stitch the world together, maybe we’ll stitch the world together.

I would be remiss if I didn’t close with the miracle of swifts, perhaps the most aeroecological species on the planet. That is, swifts live most of their lives in the air. Macdonald calls them “the closest thing to aliens on Earth.” A young European swift, when it drops out of the nest to make its first flight, will not touch tree or Earth for two or three years. They feed and drink on the wing, bathe in the rain, sleep with both eyes closed at high altitude. When old enough to mate, they collect nest materials on the wing too. Adult swifts duty-bound to the nest, are in touch with worldly things for a mere three months a year.

Even then, though, birds not sitting on the nest will rise in a flock twice a night, just after sunset and just before sunrise, up to eight thousand feet: their vesper flights. The title essay from Vesper Flights is full of Macdonald’s poetic language – she can really make her nonfiction sing – in part because she has been intrigued by swifts her entire life. You can hear that in her assessment of why they’re up at eight thousand feet. At that height, she says,

they can see the scattered patterns of the stars overhead, and at the same time they can calibrate their magnetic compasses, getting their bearings according to the light polarisation patterns that are strongest and clearest in twilit skies. Stars, wind, polarised light, magnetic cues, the distant rubble of clouds a hundred miles out, clear cold air, and below them the hush of a world tilting toward sleep or waking towards dawn. What they are doing is flying so high they can work out exactly where they are, to know what they should do next. They’re quietly, perfectly, orienting themselves.

As should we.

We could do no better than John Stimpson, retired Weetabix salesman in the U.K., who at the age of 80 has now built 30,000 nest boxes for swifts (and 1500 for other birds): “I get so much pleasure from wildlife,” he says. “Building these boxes is one way I can pay it back.”

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

From Slate, an interesting article on why Europe has never been a fan of air conditioning, and resists installing AC units even now as the region boils.

For a wide range of fine climate reporting, check out the Climate Desk, “a journalistic collaboration dedicated to exploring the impact – human, environmental, economic, political – of a changing climate.” Editors at the great investigative magazine Mother Jones oversee a collaboration of eighteen sources, including the Guardian, Grist, Slate, Yale Environment 360, Hakai Magazine, High Country News, UnDark, and the Bureau of Concerned Scientists.

From The Lancet medical journal, a progress report on air pollution and human health. The short version is that there has been little progress, but the good news is that the global push (slow as it is) to wean civilization off of fossil fuels will save millions of lives per year.

From Hakai, an update on the fate of negotiations at the International Seabed Authority – a tiny U.N. agency overseeing far too much of the planet – in the rush to develop environmental and legal protocols for deep sea mining. Some of you will recall I wrote about this dangerous absurdity last year in an essay titled Still Digging. Scientists know that so little is understood about these deep ocean ecosystems that decades of research are necessary before we can responsibly create guidelines for mining, standards for protection, and rules for liability. The ISA, however, is being forced to figure this out by next year.

From the Times, an opinion piece titled “The Worst Place in the World to Drill for Oil is Up for Auction,” on prospective oil drilling leases in the Democratic Republic of Congo. This includes some of the most important carbon-storing peatlands on Earth, and in some of the last remaining habitat for mountain gorillas.

From the Washington Post, the Arctic appears to be warming four times faster than expected. Forests are much more stressed than predicted, ice is disappearing more quickly, etc. If this continues, it will be much, much harder to control a runaway climate.

From Yale e360, some welcome good news about efforts around the U.S. to improve water quality and restore native habitat by rebuilding populations of grasses, oysters, and mussels.

Inspired, and inspiring writing Jason. Belated happy birthday!

For years now I have been making art about the importance of humanity remembering, or perhaps relearning, that we are part of nature. I have not read anything that puts it so clear or elegantly as this post.

Thank you