Hello everyone:

I’m excited to bring back some writing on the vast impact of our roads and vehicles on the living world. This first appeared three years ago, and so I’ve enriched and reworked the material for 2024.

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read this week’s curated collection of Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

Years ago, my son Harry and I purchased two copies of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows at midnight from the local bookstore, read well into the small hours, and then headed off together the next day to a family cabin in central Maine to finish the reading. Harry was fifteen then, and we spent a long, fine, quiet day of reading well-crafted wizarding drama, taking only brief pauses to talk carefully (the dangers of spoilers while reading different chapters). With Voldemort banished, we went to bed early because we had to rise before dawn to drive an hour to Baxter State Park in order to climb the magnificent Mt. Katahdin.

At that twilit hour, with the sky admitting light but the road and forests still black, driving feels like piloting a submarine. Headlights seem dimmer than in the middle of the night and the road-edges are nothing but a blur of fifty-mile-an-hour vegetated murk. Harry was hard asleep in the passenger seat. I didn’t see the first moose until we had drawn even with his massive hulk browsing in the bushes off the shoulder and, several minutes later, I didn’t see the second moose until she was halfway across the other lane running toward my car door.

Even now I can feel the adrenaline of that nanosecond – far too short to brake or swerve, and anyway we were on a remote, narrow two-lane with nowhere to swerve – as the long, long, dark snout of that moose suddenly loomed outside my window like the nose of a torpedo. In memory, that’s my last image of her, though perhaps I saw her dim form, lit red by my tail lights, clatter across the pavement behind me on hairy stilts stout enough to carry a ton of meat and long enough to cross the road in a heartbeat.

The adrenaline pressure hurt. Chest, fingers, toes all felt ready to burst. I didn’t stop the car – we had a mountain to climb – but I’d woken Harry up with my primal holler, and together we drove on, slower, while he kept his eyes open and I breathed through the fear and awe. I stole glances at his now alert face – an expression somewhere between alarmed and curious – and imagined over and over all that was at stake in that instant that hairy ghost of carnage appeared at my window.

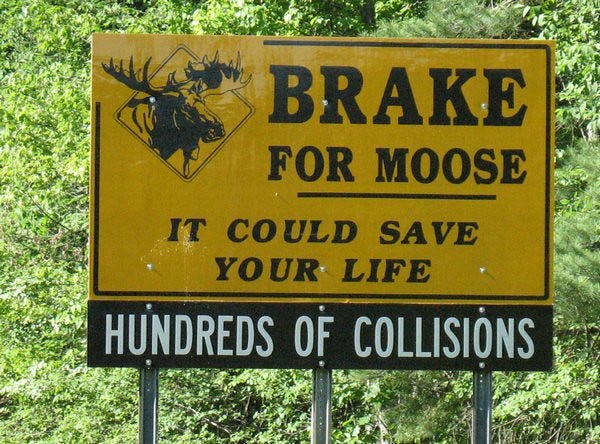

For drivers in northern Maine (and the entire north country), there’s no surprise in any of this. “Moose Crossing Next so-many Miles” warning signs are commonplace, as are stories of near-misses and destroyed vehicles. And, for that matter, this wasn’t my first moose rodeo.

Coincidentally, when I was fifteen, dozing off in the back seat of a giant 1980s station wagon moving at 20 mph through a blinding snowstorm, I woke to the sound of a thump and a black windshield becoming white again from the bottom left corner as a moose rolled over the hood like a stuntman, landed on his feet, and took off into the woods. The only damage was to a piece of chrome trim, which had been slightly bent by the yearling’s antler.

This was not a typical conclusion to a moose collision: In Maine alone, there were 1,282 reported collisions with moose between 2018 and 2022, with 1 human fatality and 16 serious injuries. In the same period there were 29,448 collisions with deer, with two deaths and 36 serious injuries. (Which means you’re nearly twelve times more likely to die in a collision with a moose.)

The vehicles, meanwhile, are very likely to be totaled. One study in the U.S. west calculated that the average collision with a moose cost $42,200.

But the Maine state statistics I’m citing here don’t include a column for moose fatality, even though these serious collisions are nearly always fatal to the animals, either immediately or as a result of their injuries.

And once you start wondering about the fate of the moose, the sturdiest of our highway victims, it’s not a long journey to start thinking about our automotive impacts on the populations of fox, deer, turkey, bear, snake, kangaroo, elk, squirrel, crab, camel, warbler, turtle, frog, sloth, butterfly, moth, and bumblebee, to name a few of those who die beneath our wheels around the world.

It is hard to overstate the impacts that roads have on the living world. Here in the U.S., vehicle collisions are the largest general cause of wildlife mortality and, for most species, the main specific cause of death. Not coincidentally, road mortality is one of the major threats to 21 federally listed threatened or endangered animal species.

In fact, our civilizational habit of driving ourselves and our stuff around is “the most extensive form of impact humans have on natural systems,” according to Fraser Shilling, co-director at the Road Ecology Center at the University of California, Davis.

The most extensive form of impact humans have on natural systems: I’ve been thinking and worrying about the problem of roadkill for years – all the carnage I see with my own eyes on the pavement but multiplied by the 4.8 million miles of America’s roads – and still Shilling’s statement astonishes me. He’s talking about natural systems, not just particularly vulnerable species like turtles or elk or panthers.

I’m sure that climate change will become a larger factor in rupturing ecosystems and landscapes, but the fact that I’m comparing climate to roads says something stark and surprising about how the way we get around has transformed the world.

Our systems of roads are also systems of roadkill. Every mile of road is a zone of death, fear, noise, and transformation in the lives of other beings. And as bad as it has been for wildlife over the last century, more is coming. Another 25 million miles of roads will be built around the world by 2050, much of it driven “through the world’s remaining intact habitats,” as Ben Goldfarb writes in his astonishing new book, Crossings: How Road Ecology is Changing the Future of Our Planet.

“Like most people,” Goldfarb writes,

I at once cherish animals and think nothing of piloting a three-thousand-pound death machine. The allure of the car is so strong that it has persuaded Americans to treat forty thousand human lives as expendable each year; what chance does wildlife have?

To really start contemplating the relationship between roads and the living world, you have to first try to see things through other animals’ eyes. As Goldfarb says,

To us, roads are so mundane they’re practically invisible; to wildlife, they’re utterly alien. Other species perceive the world through senses we cannot fathom and experience stressors and enticements we hardly register… Consider the sensory experience of, say, a fox approaching a highway: the eerie linear clearing that gashes the landscape, the acrid stench of tar and blood, the blinding lights staring from the faces of the thundering predators.

So what’s happening here? The study of “road ecology” tells us that the problem of roads isn’t simply about roadkill. It’s about how our world has created millions of miles of wounds in other species’ worlds, dividing, fragmenting, and erasing their habitats.

Our maps have been thrown down atop those of wildlife, but our paths are lanes of fire. As animals move to drink, hunt, forage, or mate, their daily journeys cross roads which can kill them. The term of art here for what’s been lost is “habitat connectivity,” and where habitat is disconnected or fractured, the life that requires wholeness either moves, suffers, or fails.

When a turkey’s path intersects with a warbler’s or fox’s, as it has since long before modern humans emerged, no harm is done. A road, though, claims turkey, warbler, and fox. And so much more. I’ve seen a scarlet tanager burst in mid-air by a passing box truck, painted turtles cracked flat like pottery fallen from a plane, too many dismembered and disemboweled deer to count, and a broken-legged hare spinning in frantic circles on the asphalt beneath passing cars.

It’s always brutal and heartbreaking, and it runs deeper than merely reducing a species’ population. As Barry Lopez asks in his classic short essay on roadkill and responsibility, Apologia, what role might these animals have played in their own communities?

The sum of our speed and our materials and our global spread and our population is a cumulative violence that scarcely exists in any form elsewhere in nature. Columns of army ants may terrorize the rainforest, and I’m sure that the great wildebeest migration in the Serengeti tramples smaller creatures each year, but army ants and wildebeest aren’t globally ubiquitous, moving at 60 mph, and taking out a million deer in the U.S., 600 camels in Saudi Arabia, thousands of red crabs on Christmas Island, and a parliament of barn owls in Ireland, every year.

Our paths and lives are cross-hatched with those of other species, but in a way that dispenses with theirs. It isn’t just that on our drives through the landscape we’re oblivious to the life with whom we share this planet. It’s that we’re actively disrupting it. In less than a century we’ve turned driving into a driver of extinction. It’s no wonder we keep our headlights on all the time these days; it’s a constant funeral out there.

This rapid transit behavior is new. No species has co-evolved over deep time to our daily acts of vehicular violence. I’m reminded of the early Antarctic explorers I’ve written about who arrived to find seals and penguins with no fear of predators on land – because Antarctica had none – and who could feed their expeditions by simply walking up to the wildlife and knocking it on the head.

The Road Ecology Center at UC Davis is devoted to studying this fundamental Anthropocene reality. It is part of a growing network of institutions around the world which have created the science of road ecology from a blend of natural sciences (for ecosystems), social sciences (for our transportation behavior), and engineering (for solutions). The REC generates research and analysis, hosts academics and conferences, partners with state and federal agencies as well as nonprofits, and develops educational outreach. Areas of interest include

how ecosystem processes at the landscape scale are interrupted by roads and the vehicles on them, how populations of plants and animals are fragmented by road systems, the demographic and evolutionary consequences of that fragmentation, and how vehicles and their pollution (including noise) cause mortality and suppress reproduction in both plants and animals.

One of REC’s achievements is CROS (California Roadkill Observation System), the world’s most extensive reporting project for roadkill and wildlife crossing. The data are invaluable for planners looking to map collision hotspots and develop solutions. (CROS is connected to the Global Roadkill Network, a scattering of similar programs in various nations that are paying attention.)

Interest in roadkill data is coming from both sides of the collisions, so to speak, as conservationists try to reduce the biological carnage and highway departments and transportation planners look to reduce the impacts on roads and vehicles and human health. Everyone involved, according to REC, has come to see that “human communities and natural ecosystems have much the same needs for sustainable and friendly transportation systems.” In other words, all life wants to live and move and thrive without fear of destruction.

Part of the problem is that we don’t see the scale of the destruction. These animals meet their deaths one by one on roads, often at night, throughout the year. Imagine instead the carcasses of millions of deer, moose, elk, squirrels and voles, coyotes and foxes, snakes and amphibians and turtles, grouse and songbirds, bears and raccoons – not to mention billions of insects – all laid out together like battlefield dead for the public to see. Every year. Imagine policymakers being asked why more wasn’t being done to prevent it.

This is also true of the human toll. The Federal Highway Administration estimates there are one to two million wildlife collisions per year, with 26,000 human injuries and 200 fatalities. These numbers are increasing. Each number is a story, often of lives altered in profound ways: a Colorado state trooper and father of two kids killed in a collision with a herd of deer; a Newfoundland wildlife conservation officer now a quadriplegic after a moose collision which shattered his C6 vertebra; a young mother in Minnesota who stopped to move a family of ducks struck and killed by a distracted driver. Often these collisions occur in areas well-known for the likelihood of collisions. That’s why highway departments put up the signs that neither drivers nor wildlife tend to read.

In financial terms, the cost to society is extraordinary. In the U.S., it’s 8 billion dollars every year, when property damage, injuries, fatalities, collision response efforts, and loss of revenue are all factored in. The FAA spends millions on research into bird strikes on planes – which costs society well under a billion dollars per year – but for a long time very little was being spent by federal or state authorities on research or solutions to vehicular wildlife collisions. There still isn’t even good basic national data on collisions and roadkill; as far as I can tell, only Massachusetts has an active program similar to CROS.

Things have begun to change. Engineers and planners and politicians and ecologists and funding institutions have come to the same conclusion: it makes good moral, financial, environmental, and public health sense to rethink how our roads fit into the larger landscape. And making huge improvements is very doable, given how bad things have become (wildlife collisions increased 50% between 1990 and 2004 while ordinary collisions were unchanged) and how much money can be saved if we were to prioritize making it easier for animals to cross roads safely. As Ted Zoli, a bridge engineer and MacArthur Fellow, put it:

“We spend $8 billion a year running over wildlife. If we took that cost and quartered it, we could build 200 animal crossings a year, and the problem of roadkill would disappear within a generation.”

Zoli was asked to judge an architecture competition for the engineering of next-generation wildlife crossings for ARC (Animal Road Crossings), an “interdisciplinary partnership working to facilitate new thinking, new methods, new materials and new solutions for wildlife crossing structures.” ARC’s larger mission, it says, is to build metaphorical bridges too:

We reconnect landscapes and wildlife habitats that have been split apart by our road systems; we reacquaint people and wildlife, helping drivers to be aware of the habitats our roads interrupt and the animals that use these places; and through these strategies, we reaffirm the need for humans and animals to coexist in the landscapes we call home.

The work being done by organizations like ARC (and its funder, the Center for Large Landscape Conservation) is, as near as I can tell, essential to the future of our relationship with the natural world. If roads are our most extensive form of impact on natural systems, then rethinking roads is crucial.

Ted Zoli was so struck by what he learned about the wildlife crossing problem that he informed ARC that he would not judge the competition. “How was it possible,” he asked, “that I, the chief engineer of one of the world’s largest engineering firms, did not know about an 8 billion dollar infrastructure problem?” Instead, he told ARC that he would enter the competition and win. He did.

Needless to say, the US isn’t yet spending 2 billion a year on wildlife crossings, but good work is finally being done in some big ways. This progress mirrors remarkable work done in Europe, Canada, and elsewhere.

And that’s the magic I’ll be writing about next week: the solutions. Some of it is really beautiful and wonderful. Like these:

And, to end on an even brighter note, here are a very cheerful coyote and badger trotting off together through a wildlife culvert crossing in California:

See you next week. Be careful driving.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

From the Guardian, the Restore Nature Now march in London drew 100,000 peaceful protesters into the street to call for a better, greener world, but it didn’t get half the media attention of the two wingnuts who dusted Stonehenge with some washable orange powder. Check out pictures of the crowd and great costumes too.

From Grist, the first 9,000 members of the American Climate Corps have been sworn in, and will soon hit the ground running, “restoring landscapes, erecting solar panels, and taking other steps to help guide the country toward a cleaner, greener future.”

Two important victories in court for rational climate policy: From the Guardian, Hawaii has settled a lawsuit from youth climate activists and agreed that the state department of transportation must “fully decarbonize the state’s transportation systems, taking all actions necessary to achieve zero emissions no later than 2045 for ground transportation, sea and inter-island air transportation.” And from the Times, Britain’s Supreme Court has ruled the local councils and planning groups must consider the total environmental impact of new fossil fuel projects, rather than just problems at the drilling sites. This may well limit the UK’s plans to expand offshore oil and gas drilling.

Also from the Times, heat waves make chemical air pollution worse, especially in urban areas. The article follows a specially-equipped van driving around NY and NJ, detecting ground-level ozone, formaldehyde, nitrous oxide, and methane. As one expert told the Times, “If you want a chemical reaction to go faster, you add heat.”

One more from the Times: a wonderful literary postscript on the friendship between novelist Cormac McCarthy and conservationist/whale biologist Roger Payne. Both “genius grant” MacArthur Fellows, they spent decades privately debating animal intelligence, the human relationship with the living world, and how to write about it. Some of you will recall I wrote a bit about McCarthy and his book The Road in a piece called Quaint, and that I’ve recommended everyone to read Payne’s final words to us all in a Time essay on weaving ourselves back into the natural world.

From Hakai, a photoessay on how replacing manual labor with drones to spray fertilizer and pesticide on rice paddies in Vietnam can reduce chemical use and runoff by 30%.

From Grist, “What your gut has in common with Arctic permafrost, and why it’s a troubling sign for climate change”: Research suggests that potential emissions from thawing permafrost in the Arctic might be twice current estimates. The clue for researchers was in our intestinal tract, where the microbiome is able to break down organic compounds that also exist in Arctic soils.

From

at , a beautiful account of wetland restoration in central Illinois, a region that has lost nearly all of its wetlands to agriculture, and of the making of Fluddles, a film about the restoration work. The restoration work connects farmers, hunters, birders, and conservationists in a vital way. You can watch Fluddles on Vimeo here.From

at , an excellent ecological explainer on the vital benefits of living shorelines (which nurture saltwater communities) vs. the seawalls, riprap, or other hard defenses people install to protect their homes. Brad advocates for better policy and incentives for homeowners to nurture their shoreline rather than armor it at the cost of natural habitat.

I wish we had the money to engineer crossings for salamanders and frogs. I help them cross the Ellsworth Road in Blue Hill/Surry on so-called big night, which is actually a series of rainy nights in early spring. Dozens of salamanders and frogs migrating to their breeding grounds walk or hop out into the road and often pause, just sitting there. I grab them and take them across if I can get to them in time. Sometimes they are run over right in front of me as I wait for a car, hoping the tires find a path that doesn't take them out. Sometimes they seem fine but perhaps paralyzed with shock. They don't indignantly stalk or hop off right away like the others but hopefully recover after a while-- I don't know because I have to get back out there to find the next customer!

Apparently it isn't all that straightforward to make a salamander/ frog crossing. I've read that they don't like tunnels because it isn't raining in there, so engineers have to find a way for the rain to drip into the tunnel. An elevated roadway would be the best but who would pay for it?

Anyway I am glad to know that engineers are working on this issue and hope we can make a lot of progress on this issue. Thanks.

P.S. All of my tree swallow nests apparently fledged successfully earlier this week.

Thank you for writing this. We

Have such a similar problem

In australia

So many millions of

Marsupials

Die on our roads. As well as monotrmes and placentals such as foxes and rabbits. Also

Birds and reptiles. It is so bloody sad we must put an end to this carnage.