Hello everyone:

The quote of the week is a bit of smart Anthropocene advice from experimental physicist and peace activist Ursula Franklin, back in 1989. Thanks to Antonia Malchik of On the Commons for sending it my way:

This planet is sick and whatever stress can be removed must be removed starting with the easiest and going to more and more difficult ones. Do all the things that are doable fast and see what happens rather than spend time on meta-strategies.

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read some curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

Sears Island in Maine’s Penobscot Bay is a hard-fought conservation gem. Some 600 of its 940 acres are protected and lined with walking trails that wind through the forest and along the five miles of shoreline. That shoreline, though, provides access to the deep waters of Penobscot Bay and, out farther, the Gulf of Maine. In recent decades, the deep water access on Sears Island has tantalized developers of a nuclear power plant, a coal-fired power plant, and a major cargo port. But all of these projects failed, in part because of fierce resistance from conservationists.

The state owns the island, and made a deal some 14 years ago to protect those 600 acres with a conservation easement, leaving aside 330 acres for potential development as a port. In the push to source Maine’s energy from renewables – the state has promised to reach “carbon neutrality” by 2045 – that potential development may soon become reality.

The state is looking to develop a 100-acre site as an offshore wind port facility, where massive turbines – up to 800 feet tall – would be assembled and shipped into the gulf as part of Maine’s bid to become an offshore wind energy leader. In the long run, this is exactly the kind of major energy project that needs to be built. The proposed facility, however, is meeting some of the same fierce opposition that defeated its predecessors.

The dilemma is, on the surface at least, a fine example of the tension between the kind of large-scale climate work that needs to happen now and the kind of local environmental protection that has preserved innumerable species and special places. Both sides respect the needs of the other but neither side has an easy answer.

Those opposed to the plan point a short distance across the bay to Mack Point, an industrial site and port already occupied by fuel tanks. The site’s owner has offered to remake Mack Point to fit the wind facility. As someone from the Friends of Sears Island told Maine Public, “So the land is available, the land owner is a willing partner, and it makes sense to us.” But the state would have to rent the land in perpetuity, rather than building on land it already owns on Sears Island. The cost difference could be hundreds of millions of dollars.

There are other issues too, environmental and otherwise (dredging, timelines, etc.), that I don’t know enough about to form a clear opinion. At a glance, either option seems fair, though I’d prefer Mack Point. The folks who love Sears Island have known all along that a third of the island was set aside for this kind of development, but then again Mack Point seems like a fine opportunity for harm reduction at a price the state can probably afford. What I find interesting about this story is the perennial tension between cost and harm, and that it’s not really a NIMBY issue, since both sites are in the same backyard.

So, how do we site renewable infrastructure correctly, and what are the obstacles to a better permitting process? What’s the best way to formulate the necessary guidance and guardrails?

As I concluded last week in the second part of this three-part series, NIMBYs really aren’t the problem, or at least certainly not compared to the obstructionism from utility companies, the opposition and disinformation campaigns from fossil fuel companies, the complexity and cost-sharing headaches of permitting projects that cross state lines, and the bottlenecks in an outdated grid.

I just found another good report on the permitting problem, “A Progressive Take on Permitting Reform,” from the Roosevelt Institute. The report emphasizes that the “red tape” and environmental permitting (NEPA specifically) that are often blamed for slowing down the energy revolution are not the problem either. It’s a thorough but readable 32 pages, or you can shortcut it by listening (as I have not) to the Volts podcast interview with one of its authors. If you want to do a deep dive on permitting reform, this report is a great place to start.

For now, though, I’ll just mention one of the report’s salient points, that “the oil and gas industry has leveraged the permitting discussion as a decoy for ramping up gas.” So when you hear the outcry about permitting, just know that the noise might have started in a fossil fuel lobbyist’s office. (There’s perhaps no better example of all this than Sen. Joe Manchin using an alleged permitting reform bill to get the Mountain Valley Pipeline declared a project of “national interest,” guaranteeing its construction, despite it being a deeply stupid carbon bomb that will cross 1,146 streams, creeks, rivers, and wetlands.) The report notes that

The industry has been one of the main political powers behind the push for permitting reform, using it to dismantle the US’s few safeguards against fossil fuel pollution instead of addressing the key forces that slow a transition to renewables.

Back in Maine, there’s been some effort to plan ahead intelligently for the new beefed-up clean-energy grid. A broad group of interested parties – utilities, state agencies, environmental groups, and more – met several times through 2020 and 2021 as the Maine Utility/Regulatory Reform and Decarbonization Initiative (MURRDI). They composed a set of recommendations, which included the need for “a holistic, long-term, strategic grid planning process.” There was a nod also to the goal of creating minimal environmental damage, especially in the construction of new transmission lines moving renewable energy from northern Maine.

More promising is a concise and practical resource from Maine Audubon, “Best Practices for Low Impact Solar Siting, Design, and Maintenance,” meant to help developers and towns site solar arrays with some basic ecological sensibility. Its recommendations include:

Preferentially use disturbed, developed, or degraded lands.

Avoid or minimize impacts to sensitive wildlife habitats and high-value natural resources.

Avoid or minimize impacts to intact forest landscapes.

Allow for habitat connectivity by avoiding or minimizing impacts to wildlife corridors..

Protect water quality and avoid erosion.

Restore or maintain native vegetation in the project area, including “pollinator friendly” species, and avoid or minimize the use of pesticides and herbicides.

The group I want to focus on, though, is The Nature Conservancy (TNC), which convened the MURRDI group and provided some forward-thinking ecological assessment to the siting of large solar projects in Maine. The Maine Dept. of Environmental Protection (MDEP) sought to responsibly streamline permitting for solar arrays, so TNC provided mapping that identifies large undeveloped blocks of important habitat that developers should avoid.

The MDEP goal was the creation of a “permit-by-rule” scenario. If a proposed array avoided these areas while meeting other fundamental environmental requirements, then permitting the project could be sped up. TNC’s ecological goal is to avoid further fragmentation of forested areas that a) support diverse life now, b) will be vital for supporting biodiversity as the planet heats up, and c) provide high quality forested carbon storage and climate adaptation. The more that renewable energy development is restricted to already developed/disturbed/fragmented areas, the better.

The mapping TNC provided MDEP is rooted in work they’re doing nationwide under the heading of “landscape connectivity.” It’s all about avoiding further fragmentation of habitat at this critical time in both human and Earth history. Already, nearly 60 percent of U.S. lands and waters are so fragmented that plant and animal species in those areas will have little opportunity to move or adapt to a hotter world. That’s why building a new energy system around the concept of landscape connectivity is so important:

Underpinning it all is the concept that species need to be able to move around the landscape… That’s why we’re working to help maintain large blocks of habitat, with a variety of pathways that connect them. That way, plants and animals can move around the landscape as conditions change, both locally and across longer distances.

Ideally, the landscapes being protected and connected are as physically diverse as they are biologically diverse. The more varied a landscape – different elevations, soil types, and other kinds of nooks and crannies – the more likely it will support a variety of life under a variety of conditions, especially as species are on the move to survive the turmoil of the Anthropocene.

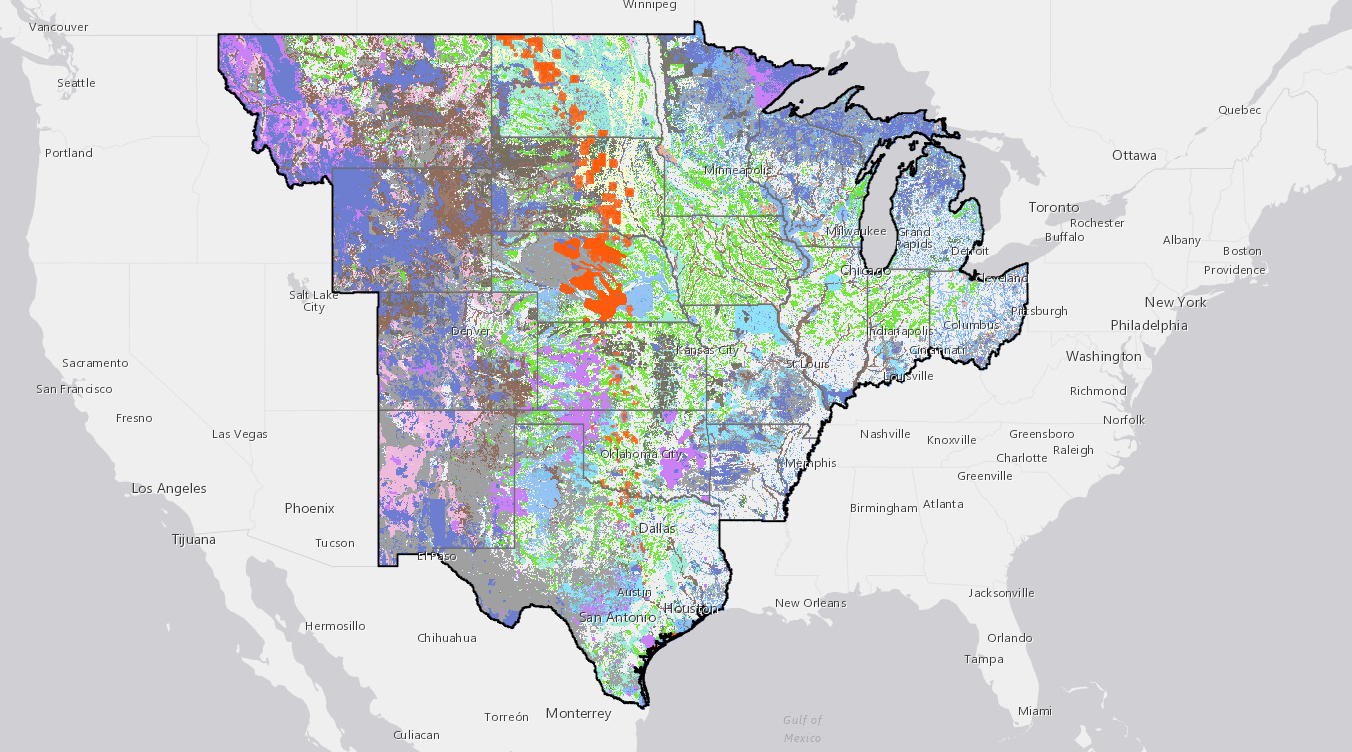

TNC’s roadmap for this is the Resilient and Connected Mapping Tool, which you can explore in depth. It’s not particularly well-designed for the layperson, but if you scroll and click through the options in the legend while zooming in and out of the U.S. areas that interest you, it’s fascinating. If nothing else, it’s easy to be impressed with the depth of analysis that TNC is providing here.

And to see how all this data plugs into the effort to make renewable energy permitting smarter and more sensitive to the land, look into TNC’s Site Renewables Right mapping tool. (The map only covers the central U.S., which has the greatest potential for wind power. I haven’t found a similar renewable siting map for the eastern or western U.S.) Here you can see with remarkable detail how ecological knowledge of, say, whooping crane migration stopovers and bat roosts and wetlands, can inform where to place (or not to place) wind turbines and solar arrays. Click on the Layers tool to decide whether you want to look at wind- or solar-related conservation data, then click on the Legend to scroll through what the various map colors identify. Perhaps the most impressive layer in the map is the one for “low impact wind potential.” This is exactly the kind of fine-grained analytical data that every state should have on hand for permitting renewables with something like a “permit-by-rule” provision.

If local, state, and federal permitting authorities emphasized and incentivized dual-use and disturbed-area siting, and then ensured that any other siting followed the environmental wisdom provided by this mapping, then I think we’d have a sane and sensible policy.

For more information, you can read an introduction by TNC to the Site Renewables Right map and, scrolling down, to several of their other renewable siting resources. And for the bigger, deeper, TNC vision here, I recommend you spend a little time with their 32-page Power of Place - National report, which finds (among many other things) that the necessary footprint for U.S. renewables can be reduced from an area the size of Texas to one the size of Arizona. I don’t have the space here to lay out those details, but the report is readable and well worth your time.

The final step in the TNC story here is their work to help create the Solar Uncommon Dialogue, a consensus agreement between “ six large solar developers, leading land conservation and environmental organizations, tribal nation representatives, agricultural interests, community groups, and investors.” (If you think this sounds like just another nice press release from overpaid consultants, know that a previous Uncommon Dialogue on what to do about the 90,000 dams in the U.S, titled “Climate Change, River Conservation, Hydropower and Public Safety,” led to “the inclusion of $2.3 billion in the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law to implement the Uncommon Dialogue agreement.”) The solar agreement lays the groundwork for a mature path to the energy transition, creating guidelines and guardrails that respect the need for the rapid energy build-out, the importance of conserving biodiversity and habitats, and the necessity of treating every impacted community fairly.

Which seems like something everyone should have thought of in the first place… But here we are, still a long way from building out the new energy systems at the speed we need. Everything about this is going to be difficult, but the more good rules we have in place the better the chaos will be.

But does any of this good rule-making that the Nature Conservancy has fostered help the good people of Searsport, or determine the fate of Sears Island? Not really. That development is one of a million unique and tough decisions being made as we thread an entirely new nervous system into the body of civilization. It’s a reminder also that what we’re building isn’t all solar arrays and wind farms. There’s lots of associated infrastructure, like energy storage, transmission lines, battery factories, and wind energy ports.

These decisions and tradeoffs are everywhere already, and we’re just getting started. Even eastern states will, according to one estimate, need to devote 1.5% to 6% of their land to solar arrays. As a great Times op-ed on how the solar/forest tension is playing out in Virginia explains,

If today’s relatively modest solar rollout is already facing such strong headwinds, imagine what will happen when states and companies move toward going 100 percent renewable.

So buckle up, everyone. The electricity generation and transmission that we rely on, and take for granted, is coming to our backyards. We have to make peace with it at the same time that we do our best to ensure that renewable infrastructure siting is being done thoughtfully, sensibly, and respectfully.

We can’t be too finicky, though, because if what’s being proposed for guidelines and guardrails delays carbon neutrality by a decade, or increases global temperature by just another tenth of a degree, the price will be the suffering and death of hundreds of millions of lives, both human and more-than-human.

As for NIMBYism, remember that if one of us, or a neighbor, or a life-minded fellow traveler in another state or country stands opposed to a particular project, we may not be NIMBYs at all. We may be working to improve an unnecessarily harmful project. We may be speaking to the ecological truth about a greener world being a cooler world. Or we may be looking to make the permitting process more sensible and sane.

But we better be damn sure about our opposition, because the world is burning.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

From Anthropocene, we burn 40 million tons of chicken feathers every year, an emissions nightmare on top of the ethical nightmare of industrial chicken production. New research has successfully demonstrated that the keratin in chicken feathers can be used to make membranes for hydrogen fuel cells.

From Hannah Ritchie at Sustainability by Numbers, a really important update to the analysis of how much mining is necessary to convert both energy and transportation systems to electric. As I’ve noted here recently, previous assessments only discussed the amount of final ore, not the massive amount of waste rock (copper, for example, makes up about 0.6% of the ore it comes from). Ritchie does an excellent job of showing that yes, the total quantity of mined material will be sharply reduced as fossil fuels (coal especially) are phased out, but the mining we need to do for electric vehicles will increase the related mining. I would still like to see a comparison of the mining footprint – the area of the Earth’s surface that will be destroyed by mining – between the two, but this is a really great start.

From Hakai, a great explainer on what we know and don’t know about the ability of kelp and other seaweeds to sequester carbon. The optimistic chatter about the promise of growing kelp to clean up our excess CO2 is still only optimistic chatter. The jury is very much out on this, and recent studies are less promising.

Also from Hakai, a good-news story of fishery management in French Polynesia, where communally-designated restricted areas are created and maintained according the ancient principle of rāhui. Rāhui have multiple meanings in Polynesian society, but in this case they’re “an area of land or water with a temporary limit on collecting a resource.” In most cases, the rāhui have been very successful, increasing biodiversity and productivity of the fishing grounds, and strengthening the role of traditional culture in managing modern resources.

From David Roberts at his Volts podcast, a long discussion (1.5 hrs) about how exactly we’ll be able to power civilization with the “variable” energy sources of solar and wind. To be honest, I haven’t listened to this yet, but the promise of it (“if you’ve ever wondered how we’re going to build an energy system around wind and solar, this is the pod you’ve been waiting for”) seems worth passing along to you.

From David Wallace-Wells at the Times, the mystery and the tragedy of the nearly unprecedented strengthening of the hurricane that destroyed Acapulco. As one expert said about the ways in which a hotter climate will impact severe storms, “we ain’t seen nothing yet.”

Finally, I want to give DeSmog a shout-out this week and highlight a few of their recent articles on the toxic shenanigans of the fossil fuel industry:

A hunger strike is underway in Texas, Louisiana, and Vietnam, protesting the awful actions of the Formosa Plastics Group, whose various companies have seriously contaminated American and Vietnamese waters. Specifically, the strike seeks to force Formosa to give compensation for a major toxic spill in Vietnam which poisoned fish and people in four provinces.

A new report from the Global Alliance for the Future of Food calls out the increasing efforts by oil and gas companies to invest in plastic packaging, fertilizers, and pesticides. If we can’t break these connections between fossil fuels and food, then the global food supply will continue to be a major contributor to emissions.

In a blow to the ten major fossil fuel companies sued by Hawaii for their lies and deception about “the climate risk of their product,” the Hawaii Supreme Court has ruled that the suit may proceed to the evidence-gathering discovery phase. The companies failed to convince the court that the suit should be dismissed because it was merely an effort to make climate policy; instead, the court agreed that the case was really about whether the companies lied. (Spoiler: they did.) As one expert noted,

Not only are [plaintiffs] going to be able to prove there’s been historic, multi-decade lying, but the lying is going on right now today. That’s going to be devastating in my view when this finally gets to a jury. And it will now get to a jury in Honolulu.

IMG_3654.jpg

Check out this photo from July. It is one of a half dozen photos from a dozen observations between mid July and August in one of our habitats in Vermont.

Looks for all the world like our Orchard Mason bee Osmia lignares, one of our 352 native species that emerges as an adult in early spring and is a terrific pollinator of apples and other early spring flowers. By the time the apple blossoms fall her work is done. Her babies are growing through larval stages and will be tucked away as adults by mid summer. So what is she doing working this cavity nest in the heat if summer? Watching her I spoke the words aloud- 'I don't know what you are.'

The answer is Osmia texana, the clue is the pinkish- purple pollen. That's from thistle.

She has no common name because she is uncommon. In fact the last time she was seen in this region was 1979. Jimmy Carter was President. There were 4 billion people on Earth, and the Village People were being sued nby the YMCA.

This one of four species we have identified in our habitats in numbers where they haven't been seen for decades.

One third of the way into the UN's Decade of Restoration, where is the policy? Where is the acreage? Hell, where is the word? Once in the MURRDI document, and your piece kindly mentions pollinators. Nowhere else.

Always enjoy your pieces. Thanks for including pollinators.

We have a strategy for creating resilience, not just protecting it.

Also, finally we have a solar field in Maine.

That pipeline photo could make you puke but to me it looks like a 100 ft wide contiguous corridor of opportunity.

Thank you for this well-researched and considered survey of some of the issues facing renewable energy siting. I am a NEPA attorney, and much of my work has involved helping nonprofit organizations fight poorly planned and poorly located resource-extraction projects. My work overlaps with renewables in a number of ways, from power line placement to wind energy and solar energy impacts on threatened and endangered species. I appreciate your presentation of the NIMBY nuances, which can be oversimplified and misrepresented in the press when traditional green groups come out against certain renewable energy projects. After all, power production, even using renewables, is never fully green: habitats are destroyed at the site of source material removal and at the end placement site, fossil fuels are deployed in manufacture, transportation, and build-out, and toxic externalities exist at all stages of production. In addition, all is for naught if renewable capacity does not replace fossil fuel capacity but is instead additive, as we see in certain circumstances. I think we must ask ourselves if destroying an ecosystem with a renewable power plant is really that much better that destroying that same ecosystem with an oilfield, just because the result is, presumably, a bit less fossil fuel used overall. It's the old "do the ends justify the means" dilemma. Maybe for some, the answer is yes. There are certainly thorny issues here!