Guidelines and Guardrails

11/2/23 – NIMBYism vs. Reality, Part 2

Hello everyone:

The quote of the week come from the good folks at Pine Tree Power:

Pine Tree Power will be a utility that works for its customers, not shareholders in faraway countries… Pine Tree Power will create economic opportunity and reinvest in the state of Maine; upgrade Maine’s grid for the 21st century so that it is ready to take on stronger winds and electrify massive parts of the state’s economy; and provide savings and ensure that everyone has access to affordable electricity, especially those most vulnerable.

This is a reminder for my Maine readers – forgive me the bully pulpit – to vote Yes on Question 3 on the November 7th ballot. It will convert the state’s two for-profit electric utilities into a consumer-owned entity unburdened by shareholder profits. Also, be sure to vote No on Question 1, which was designed and funded by the foreign owners of Maine’s current for-profit electric utilities to be a poison pill for Pine Tree Power, should it pass. If you’re still unsure, you can read an Inside Climate News article and my essay on the virtues of Pine Tree Power.

Finally, to support Maine’s Wabanaki communities, vote Yes on Question 6, which asks simply that the state of Maine print the full original text of the Maine Constitution, including its longstanding legal obligations to the tribes. That text hasn’t been in print for a century. There’s no reason to keep that constitutional language hidden.

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read some curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

Welcome back to my inquiry into the tension between what needs doing and what needs protecting in the Anthropocene scramble for a livable future.

I ended last week’s piece with these two paragraphs:

The question, then, is where to draw the line. What’s essential to protect? What climate solutions must be built regardless of biodiversity damage? Failing what Bill McKibben calls the existential “timed test” of the cooking climate will wreak unholy hell on the living world, but it’s already a pretty unholy hell for the hundreds of thousands of species being pushed toward extinction; for the billions of birds dead under windows, in the claws of a cat, or poisoned by pesticides; for the disappearing amphibians and insects; and for the severely diminished tropical forests, grasslands, and wetlands, etc.

What kind of guidance do we have – or do we need – for everything from massive federally-funded projects to the community solar arrays being presented to a local planning board? And how do we distinguish between NIMBYs pushing back against necessary things and environmentalists holding the line against poorly-planned renewable energy development?

I’ll start with a correction: There are at least a million species at risk of extinction, according to the IPBES (Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services). The IPBES readily acknowledges that a million may be a conservative estimate. And the estimate is only for plants and animals (including insects). It does not include microbes. Anyone want to guess how many endemic microbial species disappear when a large animal species does? Or when a tropical forest is erased?

Ecologically, it seems, there is no such thing as an individual, only communities within communities. An extinction should be seen, then, not only as the death of a species but as the collapse of a community and the weakening of others. Which is why, as Kim Stanley Robinson notes in his amazing Anthropocene novel, The Ministry for the Future, “extinction is the only catastrophe that can’t be undone.” (Don’t talk to me about de-extinction DNA tech, which for the foreseeable future will be as ecologically useful as repairing a split tennis ball with duct tape.)

The biological context for the world rushing to transform its energy infrastructure is not pretty. At least 10% of plant and animal genetic diversity was lost in the last 150 years. A study of 5230 wild animal populations shows they’ve dropped by an average of 69% in just the last 50 years. Eight billion humans and our livestock now make up 96% of mammal biomass, which means that every wild mammal species you can think of, and those you can’t, add up to just 4%.

Earth lost 89,000 square miles of forest cover just last year, and that’s an improvement. Grassland ecosystems in the U.S. and Canada have been erased by 62% and 80%, respectively. Globally, a quarter to a third of wetlands have been lost since 1700. We’ve altered 70% of the Earth’s surface and cut the amount of vegetation in half. Living amid the pavement, we forget that a de-vegetated world is a warmer and more barren world.

In fact, the state of the living world is such that we are, to quote a paper everyone should read, “underestimating the challenges of avoiding a ghastly future.”

So, when a solar developer wants to clearcut 35 acres of forest for a solar array, as happened down the road from me here, should we allow it? When a trove of the minerals we need for the clean energy revolution lie like grapes for the picking in pristine habitat at the bottom of the sea, should we bulldoze it to pick them? Since wind turbines kill far fewer birds than fossil fuels, is it okay to post them along migratory pathways?

Emissions-reduction work has to happen now. Every new tenth of a degree we allow will edge 100 million more people – and innumerable plants and animals – toward an unlivable future.

And the scale of what needs to be done to end our addiction to fossil fuels is mind-boggling. As just one example, a study of what’s necessary for a timely clean energy future suggests the U.S. needs 91,000 miles of new high-voltage transmission lines by 2035. We built 236 miles of high-voltage lines in 2021.

So here we are between the proverbial rock and hard place.

Ideally, we would suddenly become a modest species which consumes less and rewilds what we’ve disrupted. But we’ll need a different religion than capitalism, and we’re not there yet. So, as we crawl out from this civilizational tight spot, here are a few ideas that seem right to me. I’m embarrassed by the extended highway metaphor, given my research into road ecology, but perhaps it’s appropriate:

There’s no clean path forward, only a cleaner one than we’re on now.

The developers, advocates, and regulators for clean energy must frame their work ecologically, but tree-huggers like me need several reality checks too. The more we delay the energy transition the more future forests we’re killing with drought, disease, and fire. Wind turbines kill a minuscule fraction of the birds killed by cats, window collisions, poisoning, and extreme heat. And data suggests that offshore turbines aren’t a threat to whales, especially compared to ship strikes, entanglements, and the fossil fuels “heating and acidifying the ocean in which whales must live,” as Bill McKibben writes, noting also that “40 percent of the world’s ship traffic is just carrying coal and oil and gas back and forth; think of the cetacean paradise if we eliminated that.”

There’s a lot of ugly mining necessary to build out the infrastructure for the switch to clean energy, but its impacts pale in comparison to those of the mining for coal, oil, and gas which is done every year. (The newsletter Distilled has a good explainer article on this, though as is typical with these articles, the description of clean energy mining downplays the actual scale of destruction. Still, though, fossil fuels are far worse.) Right now we’re in a miserable Anthropocene moment of doing both at the same time. When we fully displace coal, we’ll be in a better place.

In much of the U.S., especially here in the northeast, we aren’t accustomed to having our large-scale energy sources in view. We like our electrons coming from someone else’s distant backyard. This has been our “energy privilege,” and we should admit that having some of our energy footprint coming home to roost – as solar arrays, beefed-up transmission lines, and offshore wind farms – is a form of justice, given that until now our fossil fueled lifestyles have been drilled up in other countries and refined in other states.

There’s a link between the worst kind of NIMBYism – the I-don’t-want-to-look-at-it kind – and our attraction to mining the deep ocean floor for our new energy resources. It’s easier to think of it as a clean solution done far away than admitting it’s the devastation of a vast and astonishing ecosystem we know nothing about, and which will likely take millions of years to recover.

Yet what haunts me is that, so far, energy solutions are proceeding with nearly the same indifference to the state of the living world that caused the problems. Climate chaos is not yet the main killer of plants and animals. Habitat loss is. As we race to reduce emissions, if we don’t have a firm ecological framework guiding how we solve our problems, we won’t solve our problems. An extinction crisis powered by solar panels might be smaller, but it’s still an extinction crisis.

There’s climate math, and then there’s ecological aftermath. It boggles me that we need to be reminded that “Forests Are Worth More Than their Carbon,” as the title of an Inside Climate News article put it. Solar array siting in bulldozed deserts with endangered species or clearcut forests is a clear sign that the process is not designed ecologically. For the clearest example, take a look at the massive solar arrays covering mountains and deserts in China. I’m not sure what was lost there, but there was a hell of a lot of it. A recent update to the State of the Climate Report, whose first sentence is “Life on planet Earth is under siege,” makes it clear in its conclusion that dealing with the climate must not be a narrow task:

Rather than focusing only on carbon reduction and climate change, addressing the underlying issue of ecological overshoot will give us our best shot at surviving these challenges in the long run.

What haunts me, then, is that there has been too little guidance for the energy transition. We need guidance that is ecological but efficient, climate-driven but biodiversity-informed. Thus…

We can turn the good path into a clean highway.

Here in the U.S., to more quickly build those 91,000 miles of transmission lines, the massive solar arrays, the thousands of wind turbines, and the necessary mining, we should streamline the permitting process, but only with strong guardrails to protect the living world.

Streamlining without environmental protections will cause far too much harm. In my family’s battle against the harmful development at the botanical gardens, there was a total failure in the permit review by the Maine DEP, which in rubberstamping the project seemed to assume that a botanical garden could only have good intentions. In the rush to rebuild the nation’s nervous system, we can’t assume the same thing of the thousands of renewable energy projects. We need guardrails.

Energy developers, like any other developers, shouldn’t be making siting decisions based solely on economics. But neither should clean energy development be deliberately slowed or hijacked by the permitting process. In this time of huge energy needs and severe environmental disruption, we need to create a middle road by planning ahead.

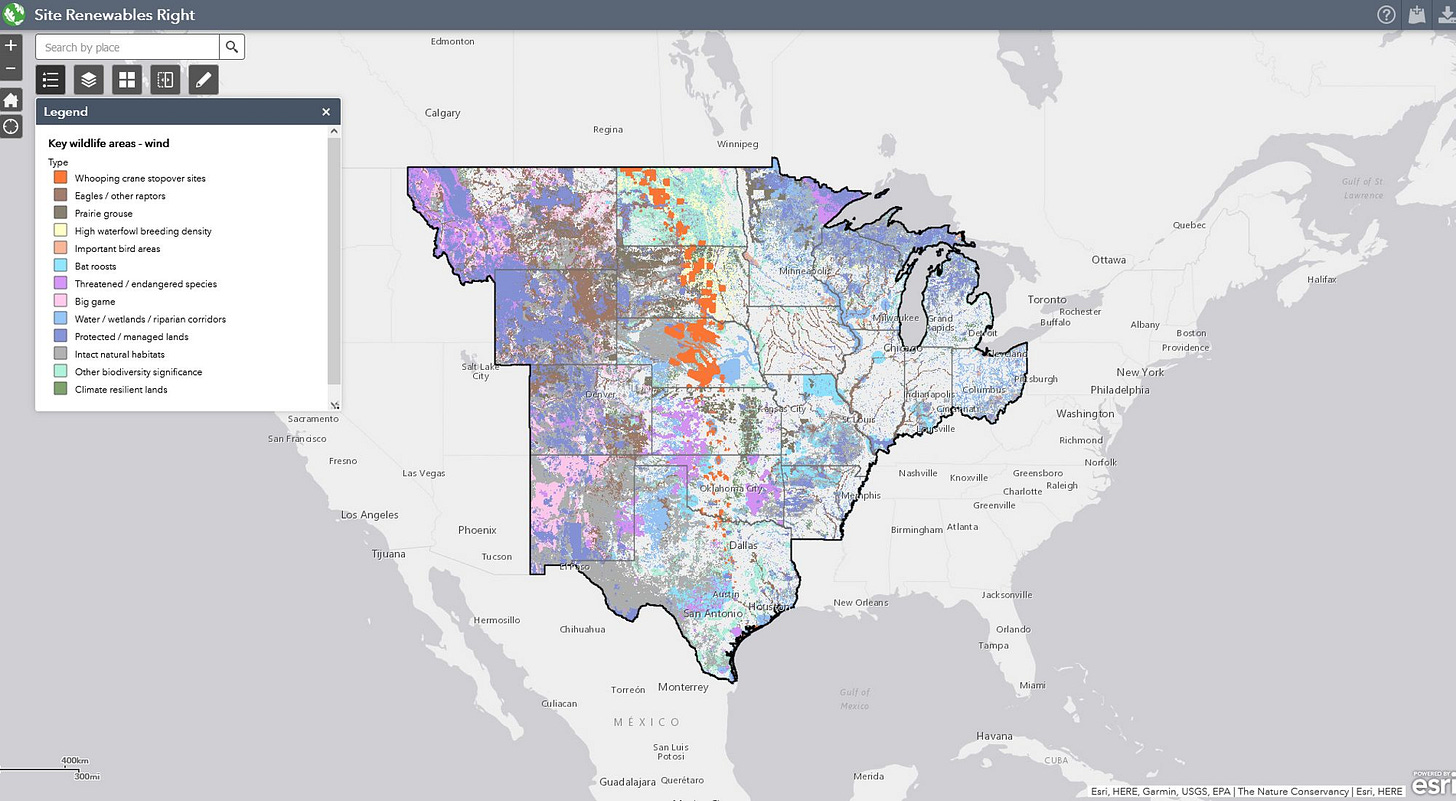

We can bake essential environmental protections into a faster permitting process by identifying a) sites to be prioritized, b) critical habitat areas to be avoided, and c) principles by which to avoid habitat loss and threatened species in general. If federal, state, and local permitting authorities, as well as developers, had this information in hand, siting decisions (in at least some cases) are effectively made beforehand. Faster approval for projects following these guidelines should be the prize.

It's common sense for people concerned about habitat loss to insist on solar and wind siting on already-disturbed areas. Rooftops, parking lots, industrial sites, landfills, highway sides and medians, and other similar sites should all be prioritized. As one opponent of clearcutting for solar in Massachusetts said, “Come talk to me when those sites are fully deployed, not before.” This has been my attitude too, but it’s often not that simple. All those sites added together aren’t nearly enough to meet energy needs, for one thing, and they’re much more expensive to develop than large-scale flat-ground sites. The cost skyrockets if an array is too far from an electrical substation. Grids have been designed around large central power plants, not for distributed power sources plugging in from all over.

That said, our current usage of rooftop and other municipal solar is pathetic, and should be maximized. 4% of American homes have panels on the roof, compared to 30% of Australian homes. Nor are public and commercial buildings being used enough. At some not-too-distant point, as the crisis intensifies, I think such dual-use will become mandatory. France is already leading the way on parking lot solar deployment.

Mother Jones calculated that if every U.S. Walmart Supercenter had a solar canopy over its parking lots, it would more than double the current solar energy capacity of the U.S., while Time found that utilizing all of the big box parking lots could generate 450% more power than current U.S. capacity. Likewise, High Country News ran the numbers on big box store rooftop solar potential in the western U.S. and found it could power 3 million homes.

But all of that is insufficient for what’s necessary in the full transition. Current capacity is growing fast but still low. Massive wind and solar sites are essential.

So how do we get communities that are resisting deployment of renewables to get on board?

The highway needs good signage.

I think that if there’s a good faith effort to put arrays, turbines, transmission lines, and mines in dual-use or low-impact sites at the same time as they’re being sited elsewhere, residents will be more likely to believe that the process is fair. If there are thoughtful guidelines in place, written with input from a broad consortium of environmental groups, scientists, industry, tribes, and developers, getting buy-in from residents and local permitting authorities should be easier.

Solar arrays look like the bad guy when they squat in a clearcut made by a developer who will profit nicely off the sale of all that timber and pulpwood, especially when the Walmart parking lot and roof down the road are still empty of panels. This, in part, is what’s creating opposition that’s stalling or banning projects.

My experience with local planning boards suggests that they don’t want to handle big philosophical or environmental questions. They want clear guidelines from higher authorities that they can measure a proposed development against. They want rules, because rules give them cover as they answer angry questions from residents. It doesn’t matter if those rules come from a state department of environmental protection or from new, enlightened federal guidelines for accelerating renewable energy projects.

And we need to continue this broader conversation about why we need the massive energy build-out, and about how to build it. It would be helpful to cultivate a “victory garden” mentality (as in WW1 and WW2, when folks at home were encouraged to grow food in their yard and in public spaces) for this phase of the Anthropocene, with increased federal incentives for rooftop panels, public arrays, community wind farms, etc., so that there was a sense of local connection to an issue of national necessity. It’s a fantasy, I know, not least because of current politics, but without an understanding of the biodiversity and climate crises, folks are more likely to protest and community officials are more likely to reject and ban such projects.

But really, to what extent are NIMBYs the problem?

The people protesting on the highway are only one obstacle among many.

Put simply, NIMBYism is not the main obstacle to climate progress. The list is long. I’ll start with the utilities, which are often for-profit regulated monopolies whose profit structure is threatened by many aspects of the clean energy revolution. They’re corporate dinosaurs built around centralized power plants. As an LA Times article on large-scale desert solar arrays explained, investor-owned utilities

across the country can earn huge amounts of money paving over public lands with solar and wind farms and building long-distance transmission lines to cities… But by regulatory design, those companies don’t profit off rooftop solar. And in many cases, they’ve fought to limit rooftop solar — which can reduce the need for large-scale infrastructure and result in lower returns for investors.

The first sentence in a Mother Jones interview titled “Big Utilities are ‘Diabolical, Man!,’” between David Roberts of the Volts podcast and David Pomerantz of the nonprofit Energy and Policy Institute, says this: “On the long list of things standing in the way of the green energy transition, utilities are up at the top.” It's a fascinating discussion that I highly recommend if you want to know what your utility is doing in the shadows. Specifically, Pomerantz explains that utility opposition to the clean energy build-out is much more important than NIMBYism:

Unfortunately, a narrative has taken over that the main obstacle to building the high-voltage regional transmission lines that we desperately need to transition from fossil fuels to renewables is, like, farmers and ranchers and NIMBY protesters… I’m not dismissing those things. There is a history of landowners not wanting transmission lines on or near their property. But it’s far less of a barrier and gets much more attention than it should compared to this big structural barrier, which is these multibillion-dollar companies that don’t want regional transmission. Utilities are very happy to build local transmission—it’s a moneymaking machine. But they’ll fight against transmission lines that weaken their assets by increasing competition, thereby driving down the price of electricity.

Sometimes, the utilities quietly fund the “grassroots” NIMBY opposition to projects that threaten their bottom line, and they’re using customer money to do it. Roberts and Pomerantz make a fine case for a major overhaul of the utilities. (Vote for Pine Tree Power in Maine on November 7th!)

Elsewhere, fossil fuel companies are funding efforts at every level to ban or slow-walk the clean energy revolution. They’ve been successful at creating a cascade of bans on solar and wind, and spreading misinformation about offshore wind hurting whales, and much more.

Meanwhile, “Transmission faces barriers at almost all phases of development,” as a Utility Dive article explains, “Planning is short-sighted, and too few lines are even being proposed.” The complexity of permitting across state lines is worsened by the need to figure out cost-sharing between the states, “and cost allocation is a key point where many projects fail.”

Finally, a Times article describes the overwhelming bottleneck of clean energy projects waiting to plug into the grid. As of a year ago, there were 10,000 wind, solar, and battery projects languishing in the interconnection queue. These projects were waiting not on NIMBYs to get out of the way, but for a) the permitting process designed for a different era to sort through the applications one by one, and b) the transmission capacity of the grids to be increased and updated (by the “diabolical” utilities).

The article is focused on federal efforts to streamline the permitting process. That, and more interesting work to weave environmental concerns into faster permitting, will be my focus next week. The Nature Conservancy, especially, has been planning ahead and providing really important information for the much-needed overhaul. There’s been good work in California, and I’m seeing good signs here in Maine.

See you in a week.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

From the Guardian, the climate emergency is a human health emergency. Medical providers, doctors, and health professionals around the globe are calling on governments to phase out fossil fuels and deal with the climate crisis, because they “increasingly see patients suffering from harm caused by climate change.”

And in related health news from the Guardian, a couple years ago 15,000 scientists signed onto a report warning that “Earth’s ‘vital signs’ worse than at any time in human history.” The report has been updated. Read it. It’s a doozy.

Some brighter news from Hannah Ritchie at Sustainability by Numbers: An updated analysis determines that the UK could, quite handily, power all of its energy needs with wind and solar. If you’re not from the UK, her explanation is still useful to read. She’s concise and clear, and the context is relevant to all of us.

From CNN, the tantalizing prospect of so-called “white” hydrogen existing in vast quantities underground around the globe. Most hydrogen energy projects have little to show so far, other than high costs, low production, and the likelihood of taking up too much of the available renewable energy in its creation. “White” hydrogen, though, exists naturally, and is more-or-less ready to use. There’s an odd color nomenclature for hydrogen: “brown” and “gray” hydrogen are byproducts of burning coal and methane, while “blue” hydrogen is collected from that burning before escaping into the atmosphere. “Green” hydrogen is collected by using renewables to split the H from H2O. Should white hydrogen be found in significant quantities, it could displace “blue” projects and supercharge some of the most energy-intense parts of the energy landscape: shipping, aviation, steel-making.

From the Intercept, “When Idiot Savants Do Climate Economics,” an important dismantling of mainstream climate economics. There is a notable schism between what climate scientists see coming and what climate economists think will happen. The problem, unsurprisingly, is that “most economists — the folks we call mainstream or neoclassical economists — have little knowledge of or interest in how things really work on planet Earth.” Which means that the economist at the center of the article, William Nordhaus,

who has been embraced as a guiding light by the global institution tasked with shepherding humanity through the climate crisis, who has been awarded a Nobel for climate costing, who is widely feted as the doyen of his field, doesn’t know what he’s talking about.

From the Guardian, a spotlight on a German city surpassing the already high German standard for recycling and reducing waste.

From Grist, we’re making the planet much saltier, and it’s a problem across natural and human communities.

From the Intercept, the terrible and toxic “advanced recycling” industry being promoted by fossil fuel companies as a solution to the plastics crisis have received millions in public subsidies.

Thank you for this well thought out piece. It is a very painful set of choices confronting us.

In making those choices, I think it's important we recognize that emitting carbon into the atmosphere isn't the only way we harm the climate. We also damage climate whenever we damage land. This is because land surfaces directly affect the temperature, humidity and air flow above them, hugely, as has been recognized for decades. So when a forests is cut for a solar array, it is not only ecologically damaging but climatically damaging. By the same token, the forest fires we are seeing are as much a result of their being dehydrated by relentless logging and monocropping as due to carbon in the atmosphere. Old, mossy forests with well developed, moisture-holding soil are naturally resistant to fire. They also help create rain, cool their regions and effect regional and global atmospheric circulations.

Unfortunately, this broader, physical AND biological understanding has been left out of the official narrative leaving us with an incomplete playbook.

In any case, your effort to thread the needle here is admirable, especially your points about utilities and the lack of rooftop solar.

I really appreciate your realistic approach with actual do-able ideas to this issue of renewables. There really is no perfect solution yet solutions we must find!