Hello everyone:

I first published a version of this essay back in 2021, and provided a short update in 2023. The deep sea mining story has lurked in the news all along, in part because the permitting drama is crawling toward a conclusion, and in part because the environmental and ethical issues remain relevant to other aspects of the renewable energy transition. Now, a recent development has compelled me to rework and update the piece for the current moment.

The topic is big, and the daily news is overwhelming, so I’ll split the essay into two pieces for this week and next.

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read some curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

Connecting to the World

I taught for several years here in Maine at a very small boarding high school - serving no more than a dozen young men at a time - who’d struggled in traditional schools. Often that meant we were working on social and emotional growth within a framework of academics, which included flexing my classes around the guys’ learning needs and personal interests.

One idea I had that we never tried was a team-taught class on the technology, design, psychology, and environmental implications of the objects at the center of their lives (and often, annoyingly, in the classroom): smartphones. From the marvelous tiny fractal antenna to the dopamine-driven notification addiction to the cobalt in the lithium-ion batteries often mined by children in the Congo, there are stories within stories within our phones. They “connect us to the world,” yes, but mostly in ways that we don’t understand or want to think about.

Let’s take a deep dive on the mining, because that’s where this week’s story takes us. Why are children mining for cobalt in the Congo? It’s wealth hiring poverty to do its dirty work, of course, but it’s also a typical Anthropocene irony, in which we try to reduce our impacts on the planet by digging the same hole deeper with a different shovel.

That is, cobalt is an essential ingredient in the lithium-ion batteries that currently power the push toward the “green” rechargeable electrification of civilization. As a Guardian article on child labor in the Congo put it, “Cobalt is found in every lithium-ion rechargeable battery on the planet - from smartphones to tablets to laptops to electric vehicles… You cannot send an email, check social media, drive an electric car or fly home for the holidays without using this cobalt,” which can be “smeared in misery and blood.”

What if we could wash away some of that misery and blood with a 4,000 meter dip in the ocean? What if we could send ROVs to scurry along the deep ocean floor and pick up trillions of potato-sized metal lumps made up entirely of manganese, iron, cobalt, copper, and nickel, gifted with traces of rare earth elements? What if we could build hundreds of millions of electric vehicle batteries with these magic metal lumps without cutting down as much rainforest, creating massive toxic waste sites, or paying a Congolese child sixty-five cents for a 10-hour day?

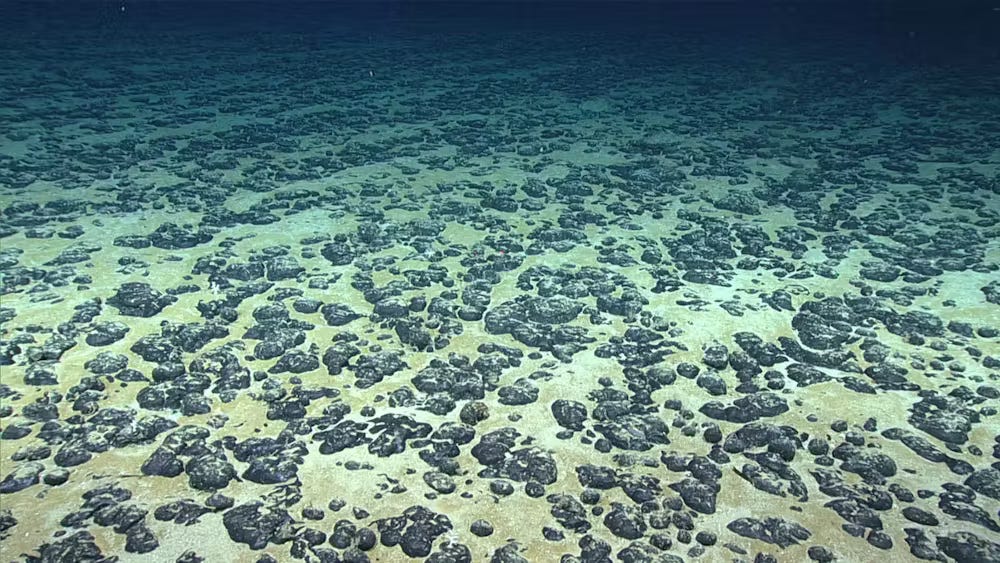

Drumroll, please… Meet your (alleged) future miracle: The polymetallic nodule.

Or as the central villain in this story, The Metals Company (TMC), calls it, “a battery in a rock” and “the cleanest path toward electric vehicles… with by far the lightest planetary touch.” The stakes are high – converting from fossil fuels to clean energy systems for at least nine billion people by mid-century – and TMC (among others) is pushing hard to make nodules the answer we’re all looking for.

And like any prospective Anthropocene mega-corporation, they’re using both a public soft sell and some hard-nosed backroom maneuvers to make it happen. On one hand, their website carefully catalogues the social and environmental ills of land-based mining for nickel (the plundering of Indonesian and Philippine rainforests), cobalt (those poor kids, plus a ton of toxic tailings for every kilo of ore), copper (loss of endemic species in Chile), and manganese (destruction of South African biodiversity).

On the other hand, in 2021, in their partnership with the tiny South Pacific island of Nauru (they have others with Kiribati and Tonga), TMC upended the slow deliberative bureaucratic and scientific permitting process of the International Seabed Authority (ISA) by triggering an obscure sub-clause in the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). That maneuver was meant to force the ISA to established rules and regulations for nodule exploitation within two years, with the threat that the Nauru/Metals Company effort may proceed regardless.

The problem, of course, is that two years is an absurdity, a blink, in the face of our ignorance of the eternal ecology of the deep sea floor.

And then, just a few days ago, the CEO of The Metals Company announced to investors that he is pivoting away from the “slow” deliberation process by the International Seabed Authority and toward the Trump administration, who he hopes will promptly offer permits to begin nodule harvesting this year.

The Area of Deep Time

But let’s back up for a moment and examine the mysteries of the polymetallic nodules and their abyssal home. You can think of the nodules as home-grown meteorites: ordinary in appearance but extraordinary in origin. Objects of deep darkness and deeper time, these nuggets are found only at depths of 3500 to 6500 meters (11,500 to 21,300 feet). They form by accretion around a fallen object like a clam shell – writers on the subject love to mention shark teeth – with the metals precipitating out of seawater or the sediment, but not in any sort of hurry: a centimeter every million years.

I’ll say that again: a centimeter every million years.

Which means, among other things, that they can only form where environmental conditions are stable on a time scale inconceivable to us. These nodules are older than our species. They sit atop sediments washed gently by the flow of Antarctic bottom water, that cold, clear, nutrient- and oxygen-rich current inching northward along the floor of the world’s oceans. That flow is part of the global conveyor belt of currents, which takes about a thousand years to make a single loop.

And the space of the abyss is as foreign to us as its relationship with time. Most of it lies away from national borders, deep under international waters - what in the euphemistic language of human supremacy we call the “common heritage of mankind” - and is referred to by the ISA simply as “the Area.”

It’s hard to overstate how little we know about the deep ocean. 70% of the planet is ocean, and 90% of the ocean is deep sea. Much of the abyssal plain remains unmapped, and nearly all of it remains unseen. As a marine scientist says in an excellent short film on deep sea mining from the Economist, “If you’re thinking about what have we actually looked at on the sea floor, it’s less than 0.001%.”

It’s always dark, always quiet, always slow, always under intense pressure, and always free from the kind of disturbances that mining would bring. Scientists once thought that the abyssal plain was a biological desert, and entities like the Metals Company are still asking us to mistake the blank spot in our understanding for an emptiness on the seafloor.

But we now know, from a handful of small-scale studies, that nodule-rich areas are surprisingly biodiverse - thousands of new species have been found, making up roughly 90% of the life that’s been observed - and that the removal of nodules would be catastrophic. In the vast abyssal floor covered with soft sediments, the nodules are the only hard surface available. Sponges attach to the nodules, and other life attaches to the sponges. This is a world inhabited also by corals, sea urchins, sea stars, jellyfish, isopods, nematodes, copepods, polychaetes, eyeless and bioluminescent fishes, cephalopods such as squid and octopus, deep sea shrimp, sea cucumbers, and sea stars. Plus countless species we have yet to observe or understand.

One of the key things we don’t know is how localized these thousands of newly-discovered species (and the far greater number still undiscovered) might be. The Metals Company suggests (without data) that the species are common across the abyss, and thus are unlikely to be threatened or driven extinct by mining across a relatively small portion of the deep sea floor. To learn the truth, however, would take many, many years of difficult, well-funded deep sea exploration, as we slowly get to know the most widespread habitat on Earth.

Extraction and Destruction Leading the Way

Instead, these decisions are being made now. It is hard to comprehend - bizarre, really - how much of the Earth’s fate is being decided by the ISA, a tiny and obscure U.N. agency. More importantly, they’re tasked with determining how best to exploit huge portions of the planet before we have even a basic understanding of it. It looks, at the moment, like yet another frontier story of extraction and destruction leading the way, with science left to examine the pieces.

As a former teacher, I sometimes feel the urge to require years-long classes in social and emotional growth for corporations, investors, and governments.

UNCLOS created the ISA to “organize, regulate and control all mineral-related activities in the international seabed area for the benefit of mankind as a whole.” That seems like a simple enough mandate, but it amounts to creating rules for mining a) that no one has ever done, b) in ecosystems hardly anyone has seen, c) over an area of nearly a hundred million square miles. To be clear, the ISA isn’t tasked with deciding whether deep-sea mining should be done in the Area, only how and where and when.

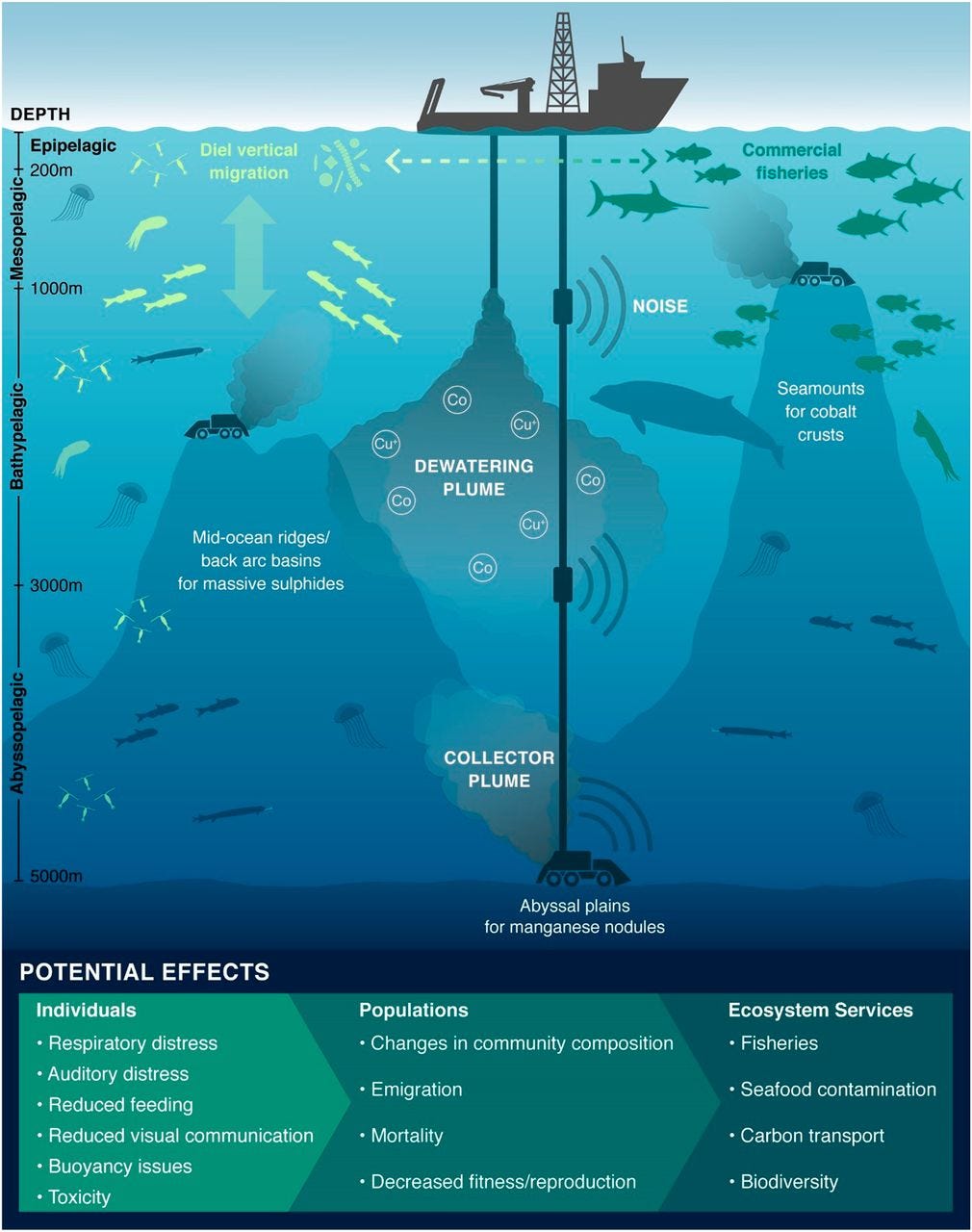

(I should note that the ISA is working on regulations for more than the fetching of polymetallic nodules. Other mining riches are available in cobalt-rich ferromanganese crusts and polymetallic sulphide deposits, both of which are associated with hydrothermal vents, those volcanic cracks in the seafloor that spew mineral-rich hot water. These vent ecosystems are extraordinarily biodiverse, supporting a marvelous array of life forms unique on Earth. For my purposes here, though, and for brevity, I’m focusing on the nodules.)

There has been criticism over the years that while the Law of the Sea was intended in part to guarantee equity for less developed nations, the ISA’s purpose seems to have been captured by the interests of wealthier nations and their mining corporations. This seems true, given that the exploration contracts (preliminary to exploitation contracts, which have yet to be permitted) given out so far have all gone to the usual suspects: China, Russia, India, Japan, France, Germany, etc., plus various companies from these nations. (The U.S. is not a signatory to UNCLOS.)

The exceptions are the three small Pacific nations (Nauru, Kiribati, and Tonga) who have partnered with The Metals Company. These partnerships, not surprisingly, allow TMC to eventually harvest their entire ISA contract areas, since the ISA requires contractors to set aside half of their explored area for the benefit of developing nations. So much for proper regulation.

Nauru has a strange and relevant history. It’s an eight-square-mile Pacific island nation with an extraordinary Anthropocene boom-and-bust story to tell. It was nearly mined out of existence through the 20th century, as more than 35 million tons of phosphates were sent off to fertilize the world’s depleted soils. When that mining wealth was squandered, Nauru became a tax haven and money laundering epicenter, then the home of a notorious Australian processing/detention center for immigrants and refugees 3100 miles off its shores. With that sad, cruel facility gone, Nauru is betting on nodules, even if it condemns much of the ocean to unnecessary exploitation. Nauruans may yet become wealthy again or, as Elizabeth Kolbert reported in “The Deep,” her New Yorker article on deep sea mining, they may go bankrupt again if they face liability costs for a mining operation gone wrong.

The ISA has no jurisdiction over seabed within the 200-mile limit of each coastal nation’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). Already, mining for diamonds in shallow waters off Namibia is common, while Japan has begun to exploit a hydrothermal vent off its coast, Papua New Guinea hosted a failed attempt to harvest a rich copper-gold deposit in its waters, and the government of the Cook Islands has passed two bills aimed at regulating and encouraging the mining of some of the estimated twelve billion tons of nodules in its EEZ.

Provided the technology pans out and the economics are sound, much more deep sea mining in various EEZs seem inevitable. Only public pressure in those countries could slow or stop it. Some mining in the Area is probably just as inevitable, but may be subject to limitation by global campaigns or diplomacy. In the end, though, as with nearly all Anthropocene exploitation, the market will determine the outcome.

I’ll be back next week to conclude this essay, focusing on the viability of deep sea mining, the long list of likely environmental harms, and the ethical quandary at the root of all of this.

For now, you can read a short summary of the topic from the IUCN (International Union for the Conservation of Nature), and check out this short film (16 minutes) on deep sea mining, Blue Peril, from the Deep Sea Mining Campaign:

And the short film (10 minutes) from the Economist that I mentioned above:

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

From

and the , two in-depth articles, “Robbing a Bank When No One’s Looking” and “Vanishing Predators and Protectors,” which together offer a hard look at the fate of the Saya de Malha Bank, one of the world’s largest and least-studied seagrass habitats, in the Indian Ocean. Seagrass meadows, Ian explains, are extraordinarily important for both biodiversity and carbon sequestration, but are much less protected worldwide than coral reefs and mangrove forests. Shark populations, in particular, have been decimated. The Saya de Malha is in international waters, and is largely at the mercy of the ships that now ravage it:More than 200 distant-water vessels - most of them from Sri Lanka and Taiwan - have parked in the deeper waters along the edge of the bank over the past few years to catch tuna, lizardfish, scad and forage fish that is turned into protein-rich fishmeal, a type of animal feed. Ocean conservationists say that efforts to conserve the bank’s sea grass are not moving fast enough to make a difference. “It’s like walking north on a southbound train,” Heidi Weiskel, Acting Head of Global Ocean Team for IUCN.

For those of you in the U.S. Pacific Northwest, or otherwise enamored with the Seattle area, check out the new book from David B. Williams: Wild in Seattle: Stories at the Crossroads of People and Nature. The book brings together 48 of David’s essays from his great Substack newsletter, Street Smart Naturalist: Explorations of the Urban Kind. The book, David says, is “focused on the geology, flora, and fauna of Seattle and her surroundings. In addition, they are paired with wonderful and whimsical watercolor images by Elizabeth Person.”

From Mother Jones, a good reporter’s journey into a fascinating, depressing, and bizarre pronatalist conference in Texas. The conference brings together the “trad” (religious conservatives) and “tech” (transhumanist obsessives) branches of the movement to revitalize birthrates, because of the delusion best expressed recently by Elon Musk to Fox News: “The birth rate is very low in almost every country, and unless that changes, civilization will disappear… Humanity is dying.” Of course, they’re really only obsessing on white birthrates, while simultaneously demonizing and criminalizing non-white immigrants. Like so much in this political moment, most of this discussion would be a ridiculous conspiracy trope if it weren’t being platformed by the fascist-friendly administration working feverishly to reshape American culture and governance. Vice President Vance, for example, is openly promoting some pronatalist talking points.

From

and The Weekly Anthropocene, another compelling article on what Sam calls “Immigrant Species Biology,” i.e. a more sophisticated and reality-based response to the sometimes hyperbolic discussion of invasive species. Sam highlights two new studies, one finding that modern conservation translocations (moving a species for conservation purposes) and biological control agents (introducing a new species to control an invasive pest) have been extraordinarily successful, with minimal harms. The other study proposes a nuanced ten-category “species spectrum” to replace our current binary native/invasive terminology. Sam also offers links to previous Weekly Anthropocene newsletters on the topic, which are equally fascinating.From

and his newsletter, a focus on two recent letters warning us about the deep cuts to (and general destruction of) American science and scientific institutions. One is from a couple thousand scientists in a Letter to the American People and the other is an op-ed in the Post from a Republican senator and a national security advisor in the first Trump administration.And, finally, back to the metals we need for the energy transition: Grist has an excellent comprehensive article on the topic.

Won’t see me driving an electric vehicle any time soon. Getting my 1980s Peugeot road bike out of hibernation this weekend. The only metal I use for transportation is vintage steel. Anything else and you’re complicit in global destruction. 😜

A marvelous essay Jason. Maybe it was reading an earlier version of it that spurred me to purchasing a large number of coffee table books on the ocean and its abysses. But I don't recall the mention of polymetsllic nodules. Those books are now in storage, their contents and the richness they conveyed to me now forgotten in my faltering memory, a metaphor perhaps for the Anthropocene as we slash and burn and stripmine our way through our brief time of suzerainity, using up irreplaceable resources before we too are forgotten. The whole world is an abyss. Deep history confounds. We know so little, yet we have so much power. Did God will that we have sovereignty and to what end? We don't know. We are as children here.