Problems Posing as Solutions, Part 3

6/29/23 – This week, just say no to E-SUVs and seafloor mining

Hello everyone:

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read some curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

This is my last installment of the problems-as-solutions theme, though I certainly could have played with it for a while longer. Our personal, economic, and ecological lives have long been shaped by bad ideas provided to us as solutions to problems we didn’t know we had. The marketers for personal care products and pharmaceuticals, just to name two examples, have told us for decades that we have bodily complaints only they can solve with expensive and environmentally harmful chemicals in single-use plastic bottles.

In the broadest view of this crisis-ridden era of human and Earth history, everything that worries us was once intended to please and empower us. Fossil fuels are a miracle of concentrated, transportable energy; plastics are the embodiment of convenience, utility, and efficiency; and artificial fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides give us extraordinary control over food production. What could go wrong?

These “solutions” provided by capitalist chemistry and technological optimism have transformed the world. Which means we now live in a transformed world. The transformation continues at an accelerated pace, and we’re all being swept downstream of decisions that have thrown the atmosphere, oceans, continents, and the balance of life itself into turmoil. Or as Vaclav Smil wrote in a Yale e360 piece,

We have been transforming the environment on increasing scales and with rising intensity for millennia, and we have derived many benefits from these changes — but, inevitably, the biosphere has suffered.

For another week of writing on problems-as-solutions, I could look ahead to the various geoengineering schemes proposed as Anthropocene solutions, or dig into the dangerous fantasy of green growth. I’m sure you could list some other misguided thinking that’s haunting us. (As always, feel free to write to me in the Comments with questions or ideas.)

To be fair, nearly everything we now propose as solutions (other than showing restraint) to the wicked problems of climate change, habitat loss, and accelerated extinctions will have at least some negative consequences. Why? Because 1) there are too many of us doing too much and using too much on a small planet, 2) because our habit is to “move fast and break things” instead of the Precautionary Principle, and 3) because corporate malfeasance and governmental paralysis have delayed for decades the kind of work that would have made civilizational transformation easier.

But here we are, facing extraordinary challenges, and the good news is we’re getting better at it. Energy systems are rapidly changing, and nations are signing on to global treaties on climate, biodiversity, oceans, and plastics. Still, though, we have an ongoing struggle to resist “solutions” that only distract us, continue the planetary harms, or make things worse. I’ve looked at the false promises of carbon capture and carbon credits, and at the hot mess of ethanol, wood biomass, and plastics pyrolysis. I’ll close out the series with a reality check on two kinds of heavy machinery doing dumb things: E-SUVs and deep seafloor mining.

SUVs and E-SUVs

Heather and I need to replace both of our cars. Our efficient little Honda Fit runs well but is rapidly becoming an engine dangling in a rusty box. To replace it, we’re looking at used Priuses, or something similar, but it’s hard to find an older car here that isn’t condemned by rust. The other car, an inherited Honda Odyssey van, is heavier and larger than we need, but it’s a California car that didn’t suffer a salty Maine youth. We figured we’d have it for many years but a few weeks ago it developed a fatal engine knock with an unpleasant habit of randomly losing power and turning off while driving.

In the wake of the pandemic, the used car market is still tight and expensive (call us if you have a deal…). We’d like to cut back to just one car, or no cars, but the reality is we live in rural Maine and work on different schedules in different places. We’re not shopping for a new car, because we’re allergic to loans and payment plans. But if we were a typical American car shopper, we’d be contemplating an SUV. It’s hard to avoid them, since they make up much of the automobile market. In 2021, they made up 52% of the market, selling at twice the rate of sedans.

The problem is that SUVs are, in general, an increasing burden on the planet, an unnecessary supersizing of ordinary transportation, a threat to pedestrians, and a very lucrative scam for the automobile industry. I feel a bit self-conscious writing about this, given that many people I know drive SUVs, and our heavy van has the same environmental issues, but we have to talk about these personal choices that have public consequences.

In the 2010s, for example, SUVs “became the second-highest cause of rising CO2 emissions, behind electricity generation,” according to Vaclav Smil. Worse, “If their mass public embrace continues, they have the potential to offset any carbon savings from the more than 100 million electric vehicles that might be on the road by 2040.” An SUV emits about 25% more CO2 than a standard car, and there were 250 million of them on the road around the world in 2020. Currently, there are just 16.6 million EVs on those same roads. As Smil writes, you can see that

the global embrace of these machines has wiped out, many times over, any decarbonization gains resulting from the slowly spreading ownership… of electric vehicles.

Elizabeth Kolbert lays out the SUV problem in an excellent short New Yorker article, “Why SUVs Are Still a Huge Environmental Problem.” Here are a few highlights:

Emissions: “Last year, the world’s S.U.V.s collectively released almost a billion metric tons of carbon dioxide. If all the vehicles got together and formed their own country, it would be the world’s sixth-largest emitter, just after Japan.”

Threats to pedestrians: “One recent study found that, if between 2000 and 2019 all the drivers of S.U.V.s in the U.S. had been driving cars instead, more than three thousand pedestrian deaths would have been avoided.”

Size: Bigger, heavier vehicles require more materials and energy to build. Even their tires produce more particulate pollution.

Industry profits: “According to a 2017 report by Automotive News, average prices for S.U.V.s and so-called crossover vehicles were up to fifty-one per cent higher than those for sedans and hatchbacks of comparable sizes, even though the S.U.V.s cost roughly the same as cars to produce.”

Bad policy: We’re incentivizing the building of inefficient cars. “In the United States, carmakers have long profited from what’s known as the S.U.V. loophole. This loophole allows auto manufacturers to get around federal regulations on fuel efficiency by selling cars that can be classified as trucks.”

And now the U.S. auto industry wants us to buy big electric SUVs instead of small electric cars. And U.S. policy is encouraging the nonsense. The Inflation Reduction Act offers tax credits for the purchase of E-SUVs with a price tag up to $80,000. Pres. Biden even celebrated the passage of the IRA’s incentives for EVs by posing with an electric Hummer.

But in a world that’s been bulldozed to the precipice, electric bulldozers won’t save us. And it’s perverse to think that somehow we can reduce our footprint by building bigger vehicles.

Perverse or not, it’s working. In 2022, for the first time, sales of E-SUVs outpaced purchases of other EVs. But these electric SUVs are often heavier than their gas versions, because of the large batteries required to power the already-oversized vehicle. Which means that, for no good reason, these beasts require more mining, use more energy, and make accidents more deadly (especially when they collide with smaller cars and pedestrians).

An Inside Climate News article notes that the electric Hummer weighs twice as much as its gas model (and three times as much as a gas-powered Toyota Corolla), and that its battery, at 3000 pounds, contains enough lithium to power 400 e-bikes. In fact, a recent report from the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy found that some E-SUVs have greater environmental impact than some gas-powered and hybrid cars.

One expert quoted by Inside Climate News didn’t pull his punches when asked about how the U.S. government is handling the SUV problem:

This is something that President Biden and U.S. DOT Secretary Pete Buttigieg have been bending over backwards to ignore, and that, I think, is a real problem… These vehicles are inefficient, make it harder to combat climate change, and are likely to kill people on our streets.

One solution is to disincentivize the purchase of SUVs by scaling car registration fees according to weight: the heavier the car, the more you pay each year (this is happening in France and Washington, D.C.). But this burden can’t just fall on consumers and their choices. I’d like to see the SUV loophole closed, IRA incentives narrowed to smaller electric vehicles and e-bikes, public transport expanded, and industry incentivized to make the cars we need rather than telling us we need to drive bulldozers. As long as the car companies can reap huge profits while making resource-hungry beasts, they will.

Seafloor mining

This July, the tiny and obscure International Seabed Authority (ISA), a quasi-U.N. agency based in Jamaica, may announce rules for mining the seafloor in international waters, an area of nearly one hundred million square miles. The ISA has already issued contracts for mining exploration, offering up 400,000 square miles of the global commons to 16 deep-sea mining contractors. The next step, whether rules are in place or not, is to grant permits for exploitation to those companies if they’re ready to harvest rare metals for the booming battery-building industry. When I say “harvest,” I mean collect by bulldozing the seafloor.

By any rational measure, the ISA is not prepared for these tasks. Scientists have scarcely begun to identify species at those depths, much less map out ecosystem needs, interspecies relationships, or the importance of these vast regions for ocean health. We have no idea what the risks or consequences will be of decimating parts of what is the largest and least-known habitat on Earth, but as an expert quoted in a BBC article diplomatically put it, “Mining could irreversibly damage benthic ecosystems.”

But the ISA’s hand has been forced. What had been a typical no-end-in-sight bureaucratic deliberation on how to regulate deep-sea mining were upended two years ago by the aggressive Metals Company, which has partnered with the tiny Pacific island nation of Nauru. Nauru, at their bidding, triggered an obscure sub-clause in the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) which gave the ISA two year deadline to complete the process. That time is up.

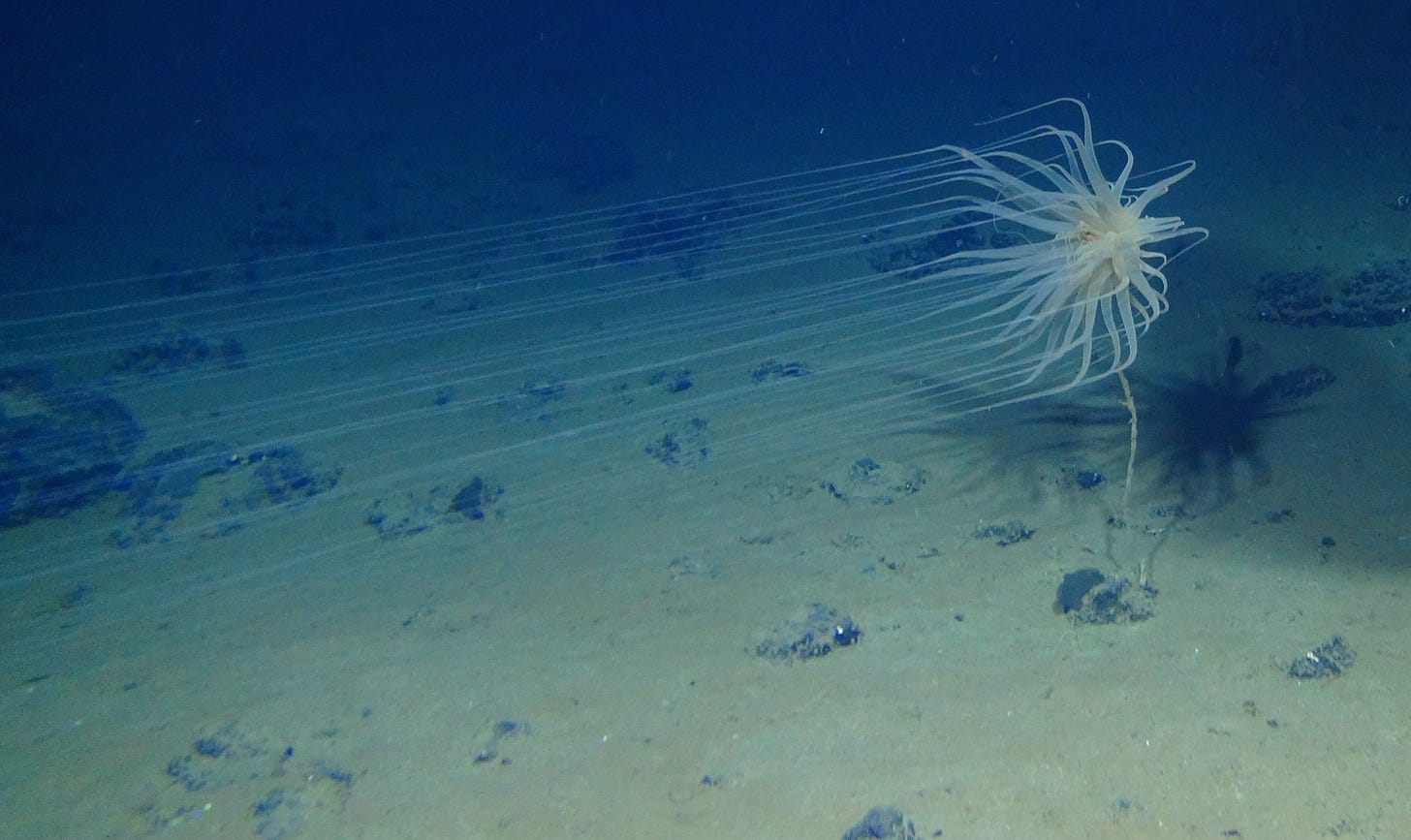

Seafloor mining, broadly speaking, is planned for two types of habitat: hydrothermal vents, those volcanic cracks in the seafloor that spew mineral-rich geothermally heated water, and the abyssal plains, the vast pitch-black and high-pressure regions of the planet that we have scarcely glimpsed. Across large areas of the abyssal plain lie scattered innumerable strange objects known as polymetallic nodules. Here’s how I described the nodules in “Still Digging,” my piece on seafloor mining from two years ago:

I think of them as akin to meteorites: ordinary in appearance but extraordinary in origin. Objects of darkness and deep time, these nuggets are found only at depths of 3500 to 6500 meters. They form by accretion around a fallen object like a clam shell – writers on the subject love to mention shark teeth – with the metals precipitating out of seawater or the sediment, but not in any sort of hurry: a centimeter every million years. I’ll say that again: a centimeter every million years. Which means, among other things, that they can only form where environmental conditions are stable on a time scale inconceivable in our daily lives. They sit atop sediments washed gently by the flow of Antarctic bottom water, that cold, clear, nutrient- and oxygen-rich current inching northward along the floor of the world’s oceans.

I can’t stop thinking about the absurd difference in timescales: The Metal Company’s rush to profit from objects that take tens of millions of silent years to form. This is the definition of unsustainable and a portrait of extraordinary selfishness.

Both the hydrothermal vents and the nodules scattered across the abyssal plains are extraordinarily unusual and ancient habitats that host life found nowhere else on Earth. We don’t know enough about them, but we know a little about how much we don’t know. And that knowledge of our ignorance – which should the origin of curiosity and awe rather than an excuse for carelessness – should shape the ISA’s approach to granting permits for seafloor mining.

Really, then, the ISA should issue a moratorium on mining until further notice. That’s what Sir David Attenborough wants, and who would argue with him? Also, the IUCN (International Union for the Conservation of Nature) voted in support of a ban, and

More than 700 science and policy experts from 44 countries signed a statement calling for a pause on deep-sea mining. In 2022, France became the first country to call for an international ban. A number of technology and car manufacturers have also called for a moratorium.

But a moratorium is unlikely to happen, because the ISA’s job is to encourage and regulate mining rather than decide whether mining should happen at all. And that means that unless something changes, the story of seafloor mining is likely to be another Anthropocene story of deep pockets vs. deep time, corporate wealth vs. a wealth of biodiversity, and of mineral riches vs. the risk of mass extinctions.

With or without rules in place from the ISA, the Metals Company may begin commercial scale collection of polymetallic nodules in the next year. Their ship-tethered harvester ROVs will scour the deep seafloor, churning up vast amounts of sediment (which is really sequestered carbon), and eliminating a habitat that may take millions of years to be reestablished.

I encourage you to read “Still Digging” for a deeper background on this important story, but there have been three recent developments, and I want to pass those on, not least because they give me a bit of hope that seafloor mining may not succeed in becoming a planetary-scale mistake.

First, as scientists desperately try to assess what’s known about the first area to be harvested, the 1.7 million-square-mile Clarion-Clipperton Zone between Hawaii and Mexico, they’ve put together a list of 5,578 new species (see more pics here) discovered in the CCZ. Only six species spotted in the region have been seen elsewhere. Basic survey work like this should inform the debate at the ISA, not least because it suggests that these species, many of which rely on the nodules for their existence, will disappear if mining occurs on too large a scale.

Second, a global treaty on protecting marine biodiversity in international waters was recently agreed upon. Known as the BBNJ (Marine Biodiversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction) or the Treaty of the High Seas, the treaty establishes for the first time in human history a mechanism for the conservation of areas and species in the lawless deep ocean. As the BBC article explains, “It's been seen as crucial for supporting the aim to protect 30% of the oceans by the year 2030. At the moment, we protect just a little more than 1% of the high seas.”

But it will take many months for the treaty to be ratified and implemented, so the hope is that the momentum from the High Seas Treaty will carry over into the debate at the ISA. At the very least, though, in the years ahead we have a tool for setting aside entire regions of the deep sea that haven’t yet been impacted by mining.

Third, an excellent Nautilus article questions the basic premise behind the push to mine the seafloor, that 1) the world desperately needs these minerals for the electrification of everything, and 2) there are billions of dollars to be made. Despite the hype, the economics may actually be terrible. Here’s why:

Logistical costs: All deep ocean projects, whether for oil and gas or for other purposes, tend to cost far more than planned.

The cruel ocean: Operating complex machinery in the deep ocean means fighting against freezing temperatures, corrosive salinity, and pressure intensive enough to crush submarines.

Liability: Mining companies may end up liable for major disruptions of carbon sequestration in the ocean, or for impacting commercial fishing.

Lack of necessity: There’s probably plenty of land-based sources to provide what we need. More importantly, battery recycling is becoming more common, and new battery technology is already emerging that uses less – or none – of the metals that the mining companies will spend billions to fetch. It’s likely that these metals will soon lose much of the value.

Market failure: The giant shipping company Maersk has withdrawn from its arrangement with the Metals Company, and the Metals Company’s stock price has for various reasons dropped by over 90%. This is a new investment, and will likely remain volatile, but it won’t take much doubt in the market to pull the rug out from the entire industry.

The unknowns: “There are just so many unknown factors in terms of understanding what the environmental impacts will be… but I think there are equally many things not understood in terms of what the economics will be.”

Failure to find funding: For the reasons cited above, and others, the investment community may well decide to steer clear of seabed mining as a way to make money.

The Nautilus article interviews private equity investor (and ocean explorer) Victor Vescovo, who very sharply criticizes the financials of seabed mining. You can watch his compelling talk at the Explorer’s Club on the topic. “I don’t think it works technologically or financially,” says Vescovo. “If you want to stop deep-sea mining,” he suggests, “you have to stop the funding.”

So let’s do that. After all, all of these problems posing as solutions that I’ve written about these last few weeks, whether ethanol, carbon credits, or seabed mining, would never have been a problem if they didn’t have major funding behind them.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

From @Bill Davison at @Easy By Nature, a wonderful story titled “A Five-Year-Old Hijacked My Garden Tour,” about the vibrant and necessary connection children and teens have with nature when encouraged.

From Yale e360, an encouraging report on tree growth across much of Africa. Deforestation is still occurring, especially in the Congo basin, but there has been a surge in agroforestry – trees planted by farmers in and around their fields – that has produced hundreds of millions of trees and improved farm productivity. It’s a pretty amazing story, not least because farmers have been doing this largely in spite of advice provided by agricultural authorities, both local and foreign.

From the Times, the uphill battle to rewild parts of Ireland, where only 1% of its native forests remain.

From Mother Jones, “What to Know About the Groundbreaking Climate Change Lawsuit in Montana,” an interview with a climate law lawyer who does an excellent job explaining the details of the case and its importance.

From Hakai, “The Atlantification of the Arctic is Underway,” about the discovery of Atlantic fish in Arctic waters, another sign that there’s an oceanic shift up north as fossil fuel emissions melt the sea ice and warm the sea.

From the MIT Technology Review, “What Rewilding Means,” a review of three new books on rewilding, and an excellent exploration of the complexity between conservation, preservation, and ecological restoration. Among its highlights is a reminder that we should be learning from Indigenous practices rather than pretending we have an equal or greater claim to ecological knowledge.

In related news from Mongabay, there’s been a significant increase of land ownership by Indigenous and local communities over the last several years. The increase is 254 million acres, bringing the total up to 11% of Earth’s terrestrial surface. This is a vital trend, because securing rights for Indigenous and local communities to their ancestral lands is perhaps the single most successful tool for conservation.

In some other excellent news from Mongabay, Iceland has suspended its whaling season (they had planned to kill 200 fin whales), and may be done with whaling forever. Iceland was one of the last three whale-hunting holdouts, with Norway and Japan, but the Icelandic government has a law against animal cruelty, and research into the slow, painful death of the fin whales finally turned the tide.

From Reasons to be Cheerful, a hopeful story about the FireGen collaborative and their effort to center Indigenous knowledge into fire management practices while also bringing young people into the conversation about the role of fire in the landscape.