The Acid Test

6/26/25 - Whether we will be who the oceans need

Hello everyone:

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read some curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

The Ballad of the Sea Butterfly

Of all the advice you might receive on what to do now in facing up to the brutal, unethical, and eco-ignorant members of the coup transforming U.S. governance, you’re unlikely to be told we need millions of people converging on Washington, D.C., holding signs that read “SAVE THE PTEROPODS!” Nor is there likely to be a large Sea Butterfly Coalition forming among members of Congress.

Which is a shame. Because if we lived in anything like an ecologically literate and science-centered society whose stories wove us deeper into - rather than farther away from - the realities of life on Earth, we’d be represented by folks who knew that the fate of the sea butterflies is our fate too.

Sea butterflies (and their cousins the sea angels) are pteropods. Pteropods are tiny marine gastropods, free-swimming ocean snails with modified “wings” that flap in a figure-of-eight pattern, allowing them to feed on phytoplankton and zooplankton in the darkness of seas from Pole to Pole. They are essential to the marine food web, as predators of plankton and - as “the potato chips of the sea” - as prey to salmon and many other species. Many sea butterflies have transparent shells, at once a portrait of physical fragility and evolutionary ingenuity.

But rather than allying ourselves with the small and beautiful, we’ve been forced instead to tie our fortunes to those of too-big-to-fail fossil fuel companies (whose products are directly subsidized with about $1.5 trillion dollars per year) and their overpaid executives. But it should be clear by now that their fortunes are not being shared with us. We receive only the consequences of their actions (and of our consent), dirty fuel and a burning world.

Nowhere in that grossly inefficient chain of events - drilling, corporate welfare, transport, refining, combustion, pollution, and heat - is there even the least empathy for life or the merest understanding of how to sustain it. All of this “cheap” energy has jolted forward civilization “forward” with remarkable benefits for some humans but at catastrophic cost to nearly every other species. Which means that from an ecological perspective it’s been expensive and backward. And, in the end, that’s the only perspective that matters.

Most life is small or microbial, and most life (80% of Earth’s biodiversity) is in the oceans. We, on the other hand, are top-heavy, terrestrial, hypersocial megafauna currently convinced that the song our societies sing has a sustainable melody. The ballad of the sea butterflies, however, tells a different story.

Too Many Coal Mines, Too Many Canaries

We seem to be surrounded by canaries in coal mines these days. Or, rather, with a wave of our coal-powered wand we’ve turned species across the globe into little yellow-feathered metaphors. Everywhere we look there are biological symbols of fragility - with their populations declining and their habitat toxic or lost - in the world we’re making more fragile. What is a plant or animal’s path to extinction, after all, but a tunnel into darkness?

Look to the Arctic and see polar bears and other ice-dependent species struggling to adjust to an ice-free summer. Look to both Poles and see Earth’s cryosphere losing in decades what was accumulated over millennia. Monarch butterflies are a popular canary here in North America, representing the hundreds of threatened moth and butterfly species most of us don’t recognize and won’t miss. Alongside them in their aeroecological wonder are the migratory birds finding too few safe places to land, and the bats finding too few safe places to roost.

For a quieter canary, I recommend lungwort lichen, which is prevalent across the Northern Hemisphere only in moist healthy forests where air quality is good. It’s a good neighbor that tells you if you live in a good neighborhood.

Just below the sea’s surface, coral reefs stop their singing as waters warm. Above the surface, islands and island communities are the canaries in a world of rising seas. But it’s deep in the ocean where the most dire threat to ocean life lurks. And sea butterflies are there to bear witness, as researchers from the University of Hawaii explain:

Sea butterflies have been a focus for global change research because they make their shells of aragonite, a form of calcium carbonate that is 50% more soluble than calcite, which other important open ocean organisms use to construct their shells. As their shells are susceptible to dissolving in more acidified ocean water, pteropods have been called “canaries in the coal mine,” or sentinel species that signal the impact of ocean acidification.

Their research found that the pteropods have been around for nearly 140 million years, having survived Earth’s last mass extinction and its more acidic seas. This might offer some big-picture hope, but “it is unlikely,” one researcher noted, “that pteropods have experienced global change of the current magnitude and speed during their entire evolutionary history.” Only a major asteroid impact can alter the Earth more quickly than humans have.

Ocean acidification is a truly staggering and far-too-seldom-discussed crisis for life on Earth. The ocean has been mildly alkaline since long before the rise of humans, but now, due to the flood of CO2 we’ve emitted (and are still emitting) globally over the last century or two, the oceans are awash in excess carbonic acid. Seawater has become 40% more acidic since pre-industrial times, though nearly half of that acidification has occurred in the last 40 years.

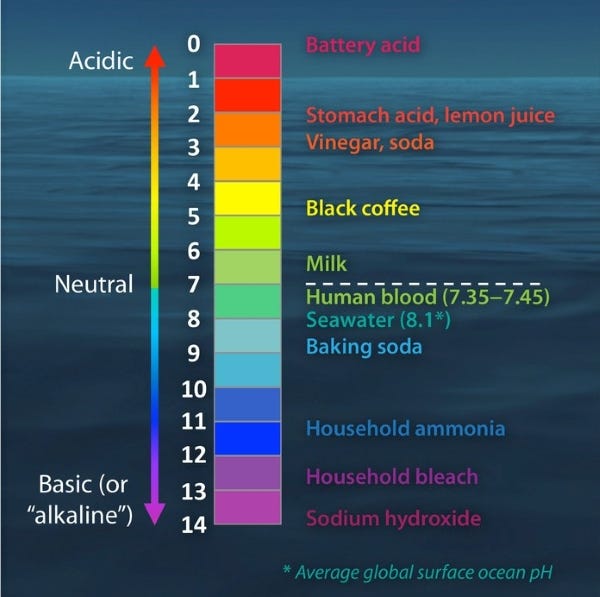

That 40% shift looks like nothing on the pH scale, a mere nudge from 8.20 to 8.05. But the pH scale is logarithmic, meaning a shift of just one point is a ten-fold change in alkalinity or acidity.

Sea butterflies and the plankton they feed on are critical bioindicators, which is a less colorful way to phrase the canary/coal mine concept. A bioindicator is what it sounds like: a species whose status in an ecosystem is assessed as an indication of that ecosystem's health. In the case of these little snails masquerading as butterflies in the deep dark sea, that health report is looking bleak.

Here’s a series of images of a sea butterfly shell, taken over 45 days, as it dissolves in seawater with the pH predicted for the year 2100, if we don’t mend both our ways and the ocean’s chemistry:

The Evil Twin

Ocean acidification is often described as the “evil twin” of climate change. It’s a good use of a soap opera trope for drawing attention to a problem that will be far more catastrophic than most people realize, but the phrase a) weirdly assumes that a warming climate is somehow less evil, and b) misses the cause-and-effect relationship between emissions and acidification. Still, it gets our attention, so I’ve given it some space here.

Here’s a quick sketch of the scale of the ocean acidification problem from Copernicus Marine Service:

Seawater is acidifying 10 times faster than any time in the past 300 million years

The ocean is more acidic today than it has been for more than 20 million years

Ocean acidity is projected to double or triple by 2100 unless we reduce our carbon dioxide emissions

Areas such as the Arctic and Antarctic are seeing significantly larger decreases in pH than the global average…

and here is their partial list of the consequences:

Shell formation: calcifying organisms like corals, plankton and shellfish, struggle to build shells and skeletons due to higher acidity in their environment

Disruption of marine ecosystems: lower pH values can interfere with the growth and reproduction of marine organisms and the formation of coral reefs, an important habitat provider for many species – with cascading impacts in the food chain

Shoreline protection: reduced shoreline protection and increased risk of floods and erosion, caused by coral destruction

Food insecurity and economic losses: with the loss of biodiversity and weakened habitats, people reliant on seafood and coastal zones can suffer

Acidification is not a future threat. It’s here now, particularly in the deep ocean. Already, deep water corals are suffering from “coralporosis,” an osteoporosis-like weakening of coral reef structures, sometimes called “cities of the deep.” Imagine buildings and infrastructure in your city growing thin and porous, then collapsing. As the reefs weaken, they support less life, which in turn impoverishes the entire ecosystem. Because acidification is happening faster in deeper waters, those deep reefs are already living in conditions as acidic as those expected to exist across shallow seas later this century.

Likewise, delicate cracks are forming in the invisible edifice of the marine food web. What flows into the sky from our power plants, factories, and tailpipes settles into the deep sea, eroding the planktonic foundation of life itself. It’s the evil twin of chaos theory’s “butterfly effect,” in which a single ripple in one part of the world might cause radical change elsewhere. Call it the “sea butterfly effect,” perhaps, in which massive emissions from billions of humans send consequences rippling through terrestrial and oceanic habitats, down even to the sea’s depths and its smallest, most delicate inhabitants.

Another Boundary Crossed

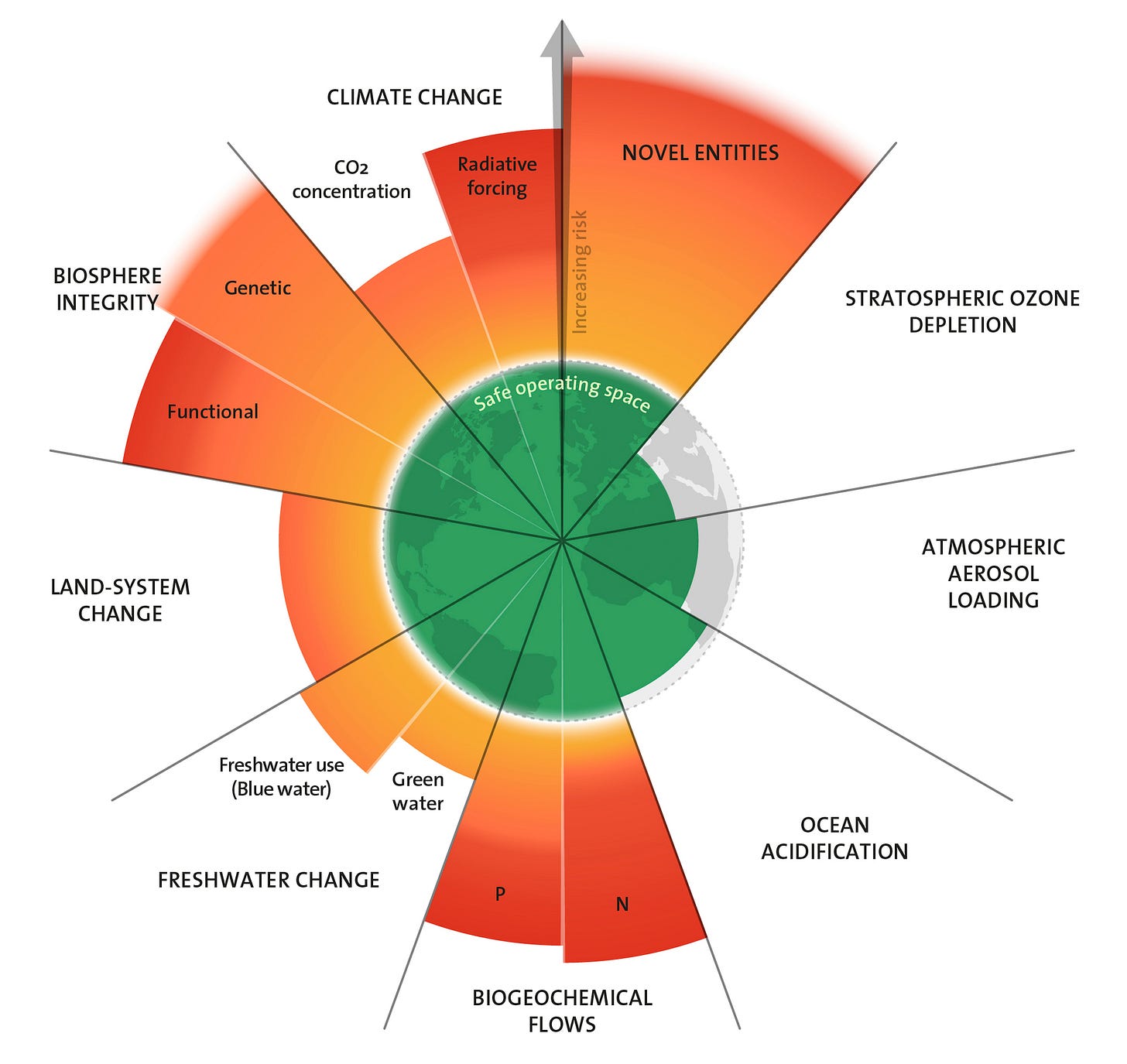

As my long-time readers know, I think the planetary boundaries concept is extraordinarily useful for understanding Earth in the Anthropocene, and for thinking about how we must face up to the work that must be done. The concept maps out “nine critical global processes that regulate the stability and resilience of the Earth,” per the Stockholm Resilience Centre, providing humans with a guide to our impacts and our path ahead.

Importantly, thinking in terms of planetary boundaries puts climate change in its proper context, as part of a suite of radical changes humans have made to the planet in just the last century or so. I think the Planetary Boundaries concept should be made more user-friendly, taught in schools at all grade levels, and discussed daily in the media.

Research on the scale and speed of ocean acidification, released earlier this month, revealed that we’ve now crossed that boundary, the seventh of nine. In fact, researchers estimate that we crossed the boundary at least five years ago.

The green zone in the graphic below is an estimate of the safe limit for each boundary category, e.g. the amount of fresh water we use, the amount of “novel entities” (synthetic chemicals, microplastics, etc) released into the environment, or the amount of loss in genetic diversity in declining populations of plants and animals (Biosphere Integrity). The extent and intensity of the orange zones indicates how far beyond those safe operating zones researchers estimate we’ve gone.

You’ll notice that Ocean Acidification in the lower right has not been updated yet. Produced in 2023, this version of the planetary boundaries graphic postdated the transition to an over-acidified ocean but predated the research that revealed it.

In this quote from an Inside Climate News report on the assessment, a researcher stresses how fast acidification is happening. I appreciate also her reference to “the little corner you care about,” which is a profound acknowledgement that the politics of ecological decline are local. We tend not to notice the transgression of boundaries unless we see it happening in our neighborhood:

“A lot of people think it’s not so bad,” said Nina Bednaršek, one of the study’s authors and an assistant professor of senior research at Oregon State University. “But what we’re showing is that all of the changes that were projected, and even more so, are already happening—in all corners of the world, from the most pristine to the little corner you care about. We have not changed just one bay, we have changed the whole ocean on a global level.”

The Acid Test

Once we’re aware of these global (and local) transgressions, what do we do? As with the more commonly discussed dilemma of climate change, we must participate in solutions to acidification at both the societal and individual levels. The first and primary solution, then, is to stop drilling for and burning fossil fuels as quickly as possible. The Herculean task of reducing emissions and replanting forests may be much easier, though, than responding to the changes that are occurring to the oceans. Increased CO2 in the atmosphere is temporary compared to how long it will linger in seawater.

The best solution would have been prevention, but that ship has sailed. We can, however, prevent acidification from getting much worse. And while that sounds unsatisfactory, it might actually save much of life on Earth.

Beyond the reduction and elimination of emissions, we seem to be obligated to actively reduce the acidity of the oceans if we want them to continue sustaining human society. Ideally, we’ll find a different magic wand that can bring ocean pH back to pre-industrial levels. But while there are some hopeful ideas being put into use, we are still very much incapable of doing that work at useful scale.

Wherever possible, the solutions to acidification must also be solutions for biodiversity. Which is why I’m drawn especially to projects that work to revitalize kelp forests and seagrass meadows. Both are excellent local sinks for CO2 and incredibly important habitats for a wide variety of ocean species. Beyond that, though, it will be necessary to expand today’s small-scale local efforts to farm kelp and other seaweeds into massive projects around the world. Research here in Maine shows that kelp farming lowers CO2 levels in the immediate vicinity and improves the growth of mussels farmed nearby.

Scaling up, though, has its problems. First, all seaweed that is harvested and utilized for human use is not sequestering CO2. Only seaweed that falls to the sea floor and is locked into sediments actually stores CO2. But recent enthusiasm for growing vast amounts of seaweed and then dumping it in the deep ocean to be sequestered, according to recent research, is “not an ecological, economical, or ethical answer to climate-change mitigation...”

Beyond these more-or-less natural solutions are the geoengineering strategies that aren’t yet ready for prime time, and may never be. These strategies generally include the dumping of of megatons of material either to enhance CO2-absorbing algae blooms or to directly alkalize the ocean, processes that carry too many risks to detail here. Suffice it to say that, in the Anthropocene, anything we do quickly at scale is likely to be unnatural and dumb. Nonetheless, these ideas are being rushed to the market to capitalize on huge investments being made by corporations more interested in green carbon credits than in real solutions. A recent Guardian article highlights the rush and the problems it poses.

The term “acid test” originates in early methods to distinguish gold from base metals. It’s now used metaphorically to refer to any definitive test of the quality of something or someone. Ocean acidification may yet prove to be our species’ acid test, a deeper and more abiding problem than even our distortion of the Earth’s atmosphere. Will we be who the oceans and their astonishing inhabitants need us to be?

When we see the pteropods as worth saving, and when Congress cares about sea butterflies, we’ll be on the right track.

Finally, here is a lovely and useful brief introduction to sea butterflies and sea angels:

And you can learn more about acidification from this quick (3 min) explainer video from Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, but I recommend taking the time to watch this longer one (15 min) from The Economist.

Beyond learning and spreading the word about acidification, the main task for those of us not working directly on ocean solutions is to help accelerate - radically if possible - the elimination of fossil fuel use and the rewilding of as much of the planet as possible. Those solutions, at least, are in our hands.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

From

, “We Will Never Forgive or Forget Those Who Sell Our Public Lands,” an appropriately hard-nosed response to the Republican senators and representatives who are betraying the public trust. They name names of all those “who are trying to sell out your birthright,” and they don’t pull their punches. I like their style:To sell off public lands – piece by piece, clause by clause, backroom deal by backroom deal – is nothing short of looting. A civic crime. A form of treason.

And it’s being done in suits and ties, with drafted amendments and polished press releases, by people who have convinced themselves that patriotism means selling the country off one acre at a time…

This is not stewardship.

It’s extraction dressed up as governance.

From the Post, like many federal wildlife facilities and programs, a vital research laboratory focused on bees and pollinators is threatened with a loss of funding from the Trump administration. “If we lose this facility and we lose these people, the hit we’re going to take to tracking bees and trying to conserve them would be absolutely devastating,” says one researcher.

From bioGraphic, a gallery of astonishing winning biodiversity photographs from the California Academy of Sciences BigPicture Photography Competition. It’s just nine pictures, but you’ll want to spend some time with each one. I’m particularly fond of the images of a female Caribbean reef octopus brooding her young and the tiny Honduran white bats roosting under a single Heliconia leaf.

From the Atlantic, Michael Grunwald (author of the new book We Are Eating the Earth) goes deep on how agriculture is a primary cause of our transformation of the planet, in both the climate and biodiversity crises. He argues persuasively that the task to make agriculture less destructive and more productive seems nearly impossible (and is decades behind schedule), but he’s optimistic about recent developments. The writing is excellent and powerful, and I certainly plan on reading the book. Here are two excerpts from the article:

Humanity’s dominion over the Earth isn’t really about the spread of cities and towns, highways and driveways, industry and commerce. It’s about farming. Of all the planet’s land that isn’t ice or desert, barely 1 percent is developed. Half is cropped or grazed. Urban sprawl is a rounding error compared with agricultural sprawl. Look out the window on a cross-country flight: The land people use to live, learn, work, and play is dwarfed by the land used to make food.

…Somehow, we’ll need to get the limited land on our hot and hungry planet to produce much more food to sustain us and absorb much more carbon to save us, because it will be impossible to decarbonize the atmosphere if we keep vaporizing trees. It’s like trying to clean the house while smashing the vacuum cleaner to bits in the living room.

From the Walrus, how three photographers are finding new ways of imaging a hotter world and its consequences, both ecological and social. It is a challenge, in a world drowning in images and other media, to tell the most important story:

As the severity and frequency of climate change–amplified events increase, the way we communicate about them will need to become ever more sophisticated. What that means in practice is employing a variety of approaches, from highly aestheticized photographs to more personal approaches to classic reportage.

From Anthropocene, a fascinating new cement-based paint keeps buildings much cooler than any other product on the market. It works like white cooling paints, reflecting most solar energy back into space, but also “sweats,” cooling by releasing moisture that it absorbs from rain and humidity. Tested in Singapore against ordinary white paint and engineered cooling paints, the new cementitious paint “reflects 88–92% of sunlight, emits 95% of heat as infrared, and holds about 30% of its weight in water.” It kept the house 4.5°C (8.1°F) cooler than the other paints, and saved about 34% more energy over an entire year.

Also from Anthropocene, urban streetlights are affecting the growing season in trees and plants more than warming in many cities. There may be some benefits amid the costs, but the disruption of natural timing is ubiquitous wherever we build our well-lit warrens.

From Grist, people around the world broadly support a carbon tax that addresses climate change and eases poverty. Even in the U.S., half of respondents signed on.

The article reminded me of David Attenborough’s latest documentary on oceans - which was an eye opener for me. Noticed some intersections - how helpful these kelp forests and corals are. Everything is so intricately interconnected and we are breaking this rhythm. It’s really sad! So much work to do!

The sea butterfly is absolutely gorgeous, such beauty and elegance! Did not know that this organism even existed - thank you for throwing light on this and the deep dive! Learning a lot through your words :)

Jason, I don’t get to your work enough, but when I do I am always glad I took the time. Thank you! There are so many things I could respond to, but I will mention 2 intersections:

1. I was a science and nature studies teacher for upper elementary kids for 25 years (ending with the pandemic), was deeply committed to focusing on both personal experience and relationship with the outdoors and fostering conceptual understanding of Earth’s life and systems. I agree that the planetary boundaries concept is a powerful way to show both system capacities and human impact—I tried to practice David Sobel’s wise adage: no tragedies before the 4th grade, but the basics of this model would have been excellent for my older kids.

2. The WashPost article about the bee lab really hit home for me. I now work part time for a local nonprofit whose mission is to increase native plantings—and reduce lawns—to support native pollinators. I will share that article out to our followers!

I’m very grateful for your dedication to educating about the heartbreak and perils all earthlings face due to the existential threat of anthropogenic climate change.

I like to hope that not everybody is immune to facts and truth.