The Extinction of Experience

5/22/25 - Ecological amnesia and shifting baseline syndrome

Hello everyone:

For a in-the-moment sense of how intensely dark and stupid the current budget bill is in relation to clean energy and a dangerously heating planet, read the latest post - “A Truly Dark Day in DC” - from The Crucial Years by

, who points out (among many other things) that the bill, if passed by the Senate as is, will add a billion tons of greenhouse gases to U.S. emissions by 2035, cripple the rooftop solar and EV industries, shut down battery innovation, and raise energy prices for all Americans. And that’s just a small part of its mindless cruelty. Call your Senators now.As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read some curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

I think it’s safe to say that we each have a fitful relationship with memory. This makes sense, given that memory is the uncertain biological storage of an uncertain physical reality: time.

Perhaps the most slippery function of our conscious lives, time acts strangely in both the physics of the tangible world and the metaphysics of our imagination. Time bends with gravity, apparently, but also seems to slow as we experience awe and wonder.

Memory making, meanwhile, is subject to the quality of our awareness (i.e. focused vs. distracted), and memory storage can be even shakier. I think often of the revelation that the memories we recall the most - pulling them off the mental shelf again and again - are the least reliable. It turns out that there’s wear and tear, with lost or reimagined details, in all that recall and re-storage of memories we’re most connected to.

Also, our minds construct stories to make sense of the fragments of experience we’ve kept, but stories can be more concerned with narrative power than with accuracy. We reimagine timelines, or remember other people’s stories as our own. We observe this in others and ourselves all the time, but how many of us are actually comfortable knowing that the line between memory and imagination is so thin? Life requires reliable information, but the human mind is an artist. We’ve evolved to be confident despite the uncertainty.

I often joke that I have a memory like a colander, with experiences strained out of time like a tangle of pasta, but it’s not that simple. Perhaps everyone’s memory works like mine; I don’t know. I’m reminded of the computer term RAM - random access memory - when I remember a childhood phone number or an obscure tidbit of Antarctic history on one hand while forgetting an old friend’s name or where my sentence was going on the other. Tomorrow, my access to memory might vary, with the phone number gone and my sentences flowing like water.

But the fact is that the mind has evolved to do much more forgetting than remembering. The immensity of experience, and the depths of the past, can only remain with us in fragments. In an amazing display of plasticity, the mind sorts, edits, contextualizes, stores, and dumps information. This is especially true now, in our information-drowned world, but forgetting is an old and invaluable evolutionary trait. Even a hunter-gatherer whose life depends on her cognitive library of food source options has forgotten the vast amount of unnecessary data that arrives daily.

In the crisis of the Anthropocene, though, as so much of the living world disappears, our evolutionary talent for forgetting has become an ecological amnesia. In this era of extinctions, memory is short and forgetting is forever.

None of us remember, and too few of us have learned about, the incredible abundance of the Earth before our species’ explosive growth in population and technology utterly transformed it. And with each generation we normalize the losses by measuring not the transformation of the last few centuries but only the most recent losses that happen in our lifetime.

This successive amnesia is also called “shifting baseline syndrome,” coined by fisheries scientist Daniel Pauly, who in investigating the 97% decline in the size of catch off the east coast of North America found that “the fishermen remained strangely unconcerned,” as this powerful Resilience essay explains:

He realized that each generation viewed the baseline as whatever they caught at the beginning of their career, regardless of how much smaller it was than the previous generation, leading to what he called “the gradual accommodation of the creeping disappearance” of fish populations.

Ben Goldfarb, in his excellent book, Eager, illustrates the idea further:

Conservation biologists refer often to the notion of shifting baseline syndrome, a form of long-term amnesia that causes each successive generation to accept its own degraded ecology as normal. Salmon fishermen who rejoice at catching ten-pound chinook forget that their fathers once hauled out fifty-pound behemoths. Modern biologists who marvel at mayfly hatches never saw the insects emerge in clouds so thick their bodies piled up in three-foot-deep windrows. Every year our standards slip a little further; every year we lose more and remember less.

In my part of the world, we rightfully mourn the family farm or beloved patch of forest lost to development, but tend to forget that the farm had been an erasure of complex habitat and fail to realize that the forest was already a thin and fragmented shadow of its ancient self.

Ecological amnesia is a social phenomenon as well as an individual one. Cultural memory is a function of what we spend our lives doing and talking about together, and what we choose to record of those experiences. As we’ve become more urban, indoor, plugged-in, and disconnected creatures, our stories and the memories we make from them became less natural too. Neither Netflix nor Grand Theft Auto are likely to help us care about the world’s staggering loss of amphibians and wetlands. Our Anthropocene storytelling edits out the plant- and animal-filled past we have not kept in mind.

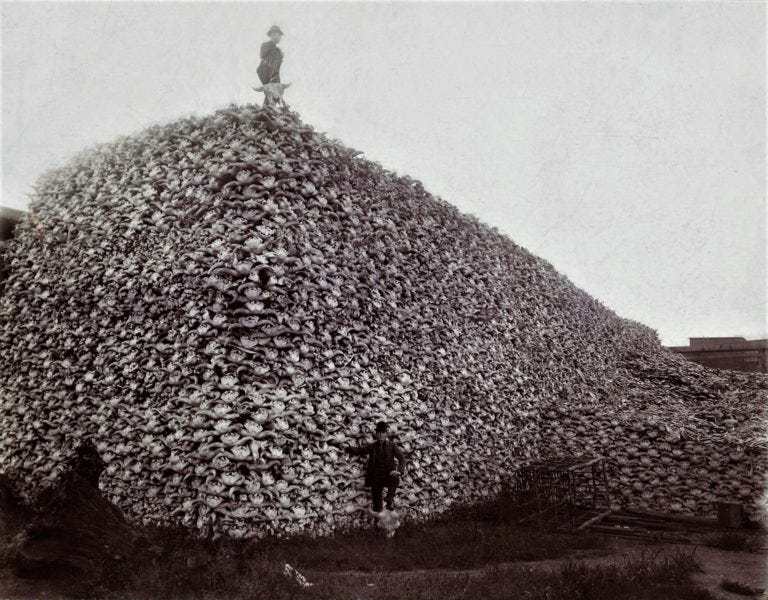

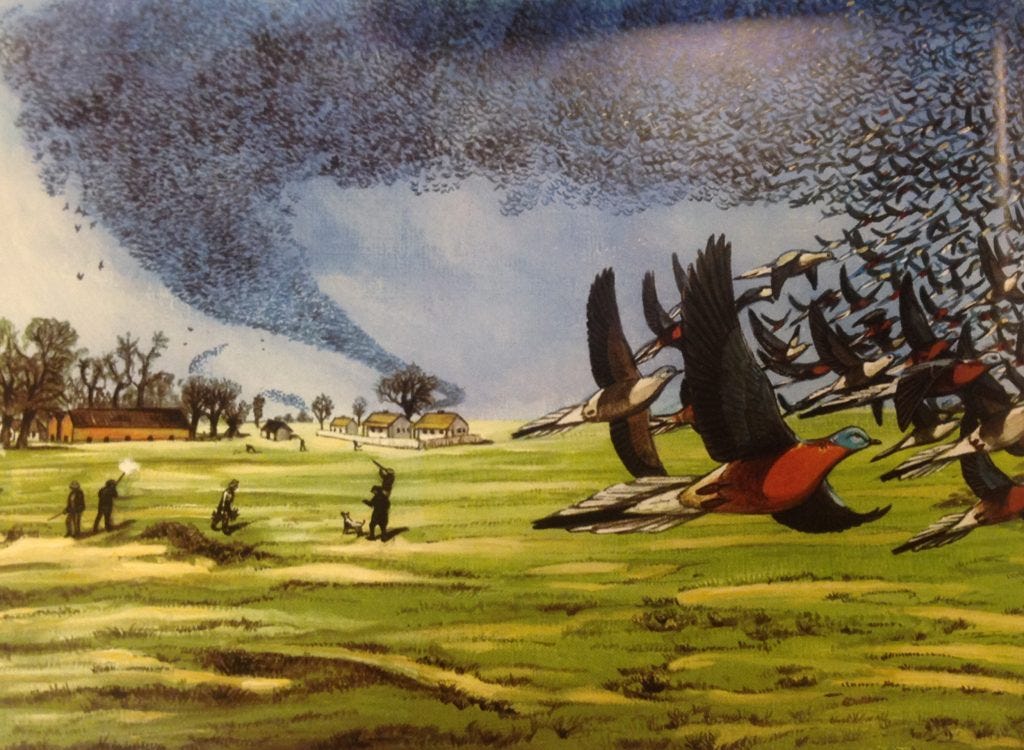

The most powerful exploration of this loss of ecological memory I’ve found is an essay by Wade Davis, published as a chapter titled “Ecological Amnesia” in the anthology, Memory, and also as a article titled “Life Without Wild Things” in The Narwhal. Davis uses as touchstones the unfathomable erasures of North America’s vast flocks of passenger pigeons and herds of bison, gazing from those species’ last stands to the world we’ve mindlessly created from the one we’ve mindlessly disrupted.

There were once 3 to 5 billion passenger pigeons. Even after the slaughter had begun, this one species made up perhaps 40% of all North American birds, blocking out the sun in flocks that passed overhead for hours on end. Likewise, peak bison population may have been as high as 60 million, with herds so large that “it took days for them to pass a single point.” By 1889, only 541 bison were left, and a decade later the last known wild passenger pigeon was shot. Both species literally shaped the continent, keystone species extraordinaire, and yet, as Davis notes, there are no shrines of promise or monuments of regret, no “memorials to the victims of the ecological catastrophes.”

The pigeons are a blank spot in our collective memory, and the bison, while back from the brink, are as absent in our minds as they are on the land. Davis reflects on our shortsightedness:

As I thought of this history, standing in that tall-grass prairie, what disturbed me most was the ease with which we have removed ourselves from this ecological tragedy. Today, the good and decent people of Iowa live contentedly in a landscape of cornfields claustrophobic in its monotony.

The era of the tall-grass prairie, like the time of the buffalo, is as distant from their lives as the fall of Rome or the siege of Troy. Yet the terrible events unfolded but a century ago, well within the lifetime of their grandparents. This capacity to forget, this fluidity of memory, has dire implications in a world dense with people, all desperate to satisfy their immediate material needs. Confronted by the consequences of our actions, there is always the path of forgetfulness.

Davis moves outward from his Iowan cornfield to a world constantly being deprived of life to support a growing human population increasingly unaware of the long-term erasures made for our short-term benefit. Lush Indonesian islands “converted by chainsaw and bulldozer to wasteland in a mere generation,” the Colorado River delta turned from “milk and honey wilderness” to “barren mudflats” by the 1920s, Haiti’s forests shrunk from 80% of the country a century ago to a remnant 2% today, and the salmon-rich waters of Alaska and the cod-filled seas off Newfoundland reduced by industrialized fishing to impoverished, tightly-managed resource zones.

A Resilience essay notes that in 1800, 26 million elephants roamed Africa, but now only 415,000 remain, and offers these examples from places no longer known for their abundance:

One eighteenth-century writer, standing on the shores of Wales, described schools of herrings five or six miles long, so dense that “the whole water seems alive; and it is seen so black with them to a great distance, that the number seems inexhaustible.” In the seventeenth-century Caribbean, sailors could navigate at night by the noise of massive shoals of sea turtles heading to nesting beaches on the Cayman Islands.

I would love to live in a world filled with sea turtles and passenger pigeons rather than one reduced to a biological skeleton. But, stories of good management and conservation successes aside, this decline from natural abundance to our impoverished 21st century imagination has been the setting for the human expansion everywhere.

And we are, in general, oblivious to the transformation. I include myself here too; I know the story, but not many of its details. There are so many fundamental, radical changes to the natural world most of us are unaware of. Here in North America, only 4% of the tallgrass prairie that once covered 170 million acres still remains. Chestnut trees, largely wiped out by disease, once made up 25% of the eastern forest’s hardwood canopy. Only half of wetlands in the lower 48 states still exist. An estimated 200 million beavers shaped the continent from treeline in northern Canada to the deserts of northern Mexico until slaughter reduced them to about 100,000 at about the same time the last passenger pigeon died.

And those are some of the best known examples. How many of us on this continent are aware, for example, that freshwater mussels are one the most endangered group of animals in the world? How many of us are concerned about the threat to the continent’s ecosystems from dozens of nonnative earthworm species? “Earthworms tell the story of the Anthropocene, the age we live in,” says a researcher who is concerned. “It is a story of global homogenization of biodiversity by humans, which often leads to the decline of unique local species and the disruption of native ecosystem processes.”

Decline and disruption are our companions on this path to forgetfulness.

We live in an era of unrivaled access to information about the Anthropocene transformation to life on Earth, but nearly all of the digital world is, of course, obsessed with people. Far more people have read about the new Pope being a White Sox fan than have read that paper on earthworms. Likewise, according to another study few people have read, about 90% of the threatened amphibian species listed on the International Union of Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List have never been Googled.

And even those of us paying attention are only partially aware of how much has been lost. We can see the data but we don’t have the experience our grandparents or great-grandparents had. Our stories are built on numbers and regret, both of which are a hard sell in the narrative marketplace.

What we, as individuals, don’t know now will certainly be forgotten by society later. Over time, forgetting equals extinction.

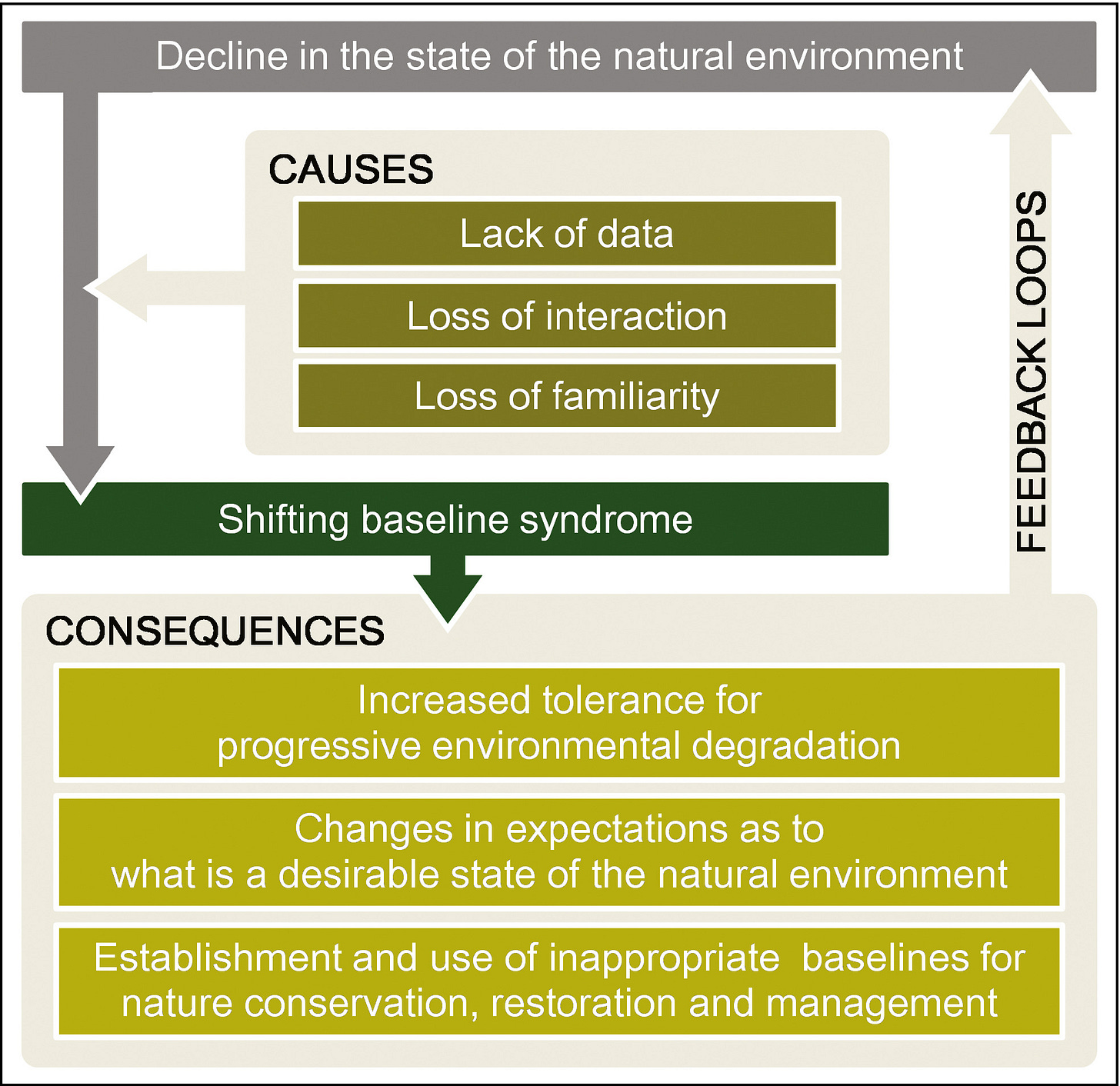

As this graphic explains, our amnesia, shifting baselines, and the decimation of the natural world create a fast-moving feedback loop. If uninterrupted, it would lead to the planet’s sixth mass extinction. Therefore, there are few things more important than figuring out how to interrupt the feedback loop, at a planetary scale.

The place to start, perhaps, is in understanding that the extinctions of plants and animals originates in part in the “extinction of experience.” The less connected we are to the outside, to our fellow species, to the great green/blue world, the less we will know or care about its disappearance. The great

at Chasing Nature wrote about this a while back:The lepidopterist, writer, and conservationist Robert Michael Pyle calls this the “extinction of experience” — our estrangement from the familiar. If we do not know what lives next to us, we will not notice when it’s gone.

“So it goes, on and on, the extinction of experience sucking the life from the land, the intimacy from our connections,” Pyle writes. “This is how the passing of otherwise common species from our immediate vicinities can be as significant as the total loss of rarities. People who care conserve; people who don’t know don’t care. What is the extinction of the condor to a child who has never known a wren?”

One the best ways to interrupt the feedback loop, then, is in the teaching of children about wrens and condors, about moss and mayflies, about salmon and bison and passenger pigeons. This is the work my wife Heather does, introducing fourth grade classes to nature education at a local nature center. After a recent session discovering macroinvertebrates in a small pond, one of her students said to her, “I wish every student in every class could come here to learn this!”

If we were so foresighted as to weave outdoor experiences and natural history into our entire education system, if children of all ages learned about the real world and what we’ve done to it, then we’d be on a multigenerational path to the creation of a more ecologically-aware society. But a thorough study of shifting baseline syndrome (from which I pulled the graphic above) explains that education is only one part of the four-part interactive solution:

Restore the natural environment (to provide more opportunity for natural experience)

Monitor and collect data (esp. long-term ecological research and citizen science)

Reduce the extinction of experience (by providing more available natural environments and increasing people’s interest in exploring them)

Educate the public (of all ages)

Science must continue to tell us stories of historical abundance to help us set accurate baselines and build a better cultural memory of our real Anthropocene ecology. Educators and artists must continue to help us reframe our relationship with the real world. And all of us must encourage each other to build and rebuild that relationship. Recovery begins with remembering, and remembering begins with experience.

And sparks of good news are everywhere amid the overwhelming crisis. Some scientists, artists, and educators are doing their work to protect and remember the lives of our fellow species. Conservation biologists devote their entire careers to the sacred work of knowing and restoring the more-than-human world. There are 10-15 million beavers now, and about 440,000 bison (though most are raised in commercial herds for meat). The passenger pigeon might even come back from the dead, if an ambitious and tech-glitzy de-extincting project succeeds.

It is vital that all of this, and much more, succeeds. As Wade Davis writes, time in an era of extinctions is a tide that continues to ebb:

In three generations, a mere moment in the history of our species, we have throughout the world contaminated the water, air and soil, driven countless species to extinction, dammed the rivers, poisoned the rain and torn down the ancient forests. As Harvard biologist E.O. Wilson reminds us, this era will not be remembered for its wars or technological advances but as the time when men and women stood by and either passively endorsed or actively supported the massive destruction of biological diversity on the planet.

Davis goes further, questioning the basic premise that human memory is a flexible, amnesiac tool which leads inexorably to destruction. In fact, he points out, nearly all of human history is marked by the deep cultural memory of many Indigenous peoples and the deeper connection to the land to which they applied that memory. They “cultivate fidelity to the deepest of memories, myths that both link the living to the ancestral past and illuminate the way to the future.”

This suggests, he writes, that “our capacity to forget and adapt to successive degrees of environmental degradation is less a human trait than a consequence of culture.” Our memory of the natural world, after all, is not simply stored in brain cells and subject to the vagaries of consciousness. We are ourselves the biological storage of time. I mean this in terms of deep time, as we (with the trillions of microbial cells that inhabit us) are complex examples of the astonishing evolution of all life on Earth, and I mean it in terms of recent time, since we are only very, very recently separated from the wilds that nurtured us in the villages and tribes which marked nearly all of human history.

We are natural. Consciousness is natural. Culture, though, is the social artifice built around rules we dream up. We just need to remember to dream up better, older rules.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

From

and In the Garden of his Imagination, “Baby Bird Day to You,” another sweet, thoughtful, and incredibly well illustrated post revealing the awesome life of birds. The birds arrive for David, and he arrives for us. Enjoy.Likewise, from

and Easy By Nature, “How the Warbler Descends,” another of Bill’s astonishing, beautiful, and poignant photoessays, this one on the passage of migratory warblers through our lives.From

and The Global Nature Beat, another great round-up of biodiversity news from around the planet. There’s nothing like the comprehensive work that Mike provides. Please check it out and subscribe, and while you’re at it check out Mike’s other Substack, , which is “devoted to stories about what I think are the world’s most fascinating plants — the strangler figs and their kin, which have shaped our world and our species in profound ways.”From Vox, a thoughtful, well-argued consideration of the case for compassionate treatment of the trillions of smaller life forms we’re on track to kill for our food, namely shrimp and insects. It can be a hard case to make, given the early days still for improving factory farm conditions for the billions of chickens, pigs, and cows we kill to eat, but evidence for sentience and pain perception in insects and shrimp is mounting.

From Grist, the ridiculous and dishonest loophole that allows plastic manufacturers to label new plastics as “recycled.”

From the Guardian, just in case you were looking for more infuriating news, two-thirds of the Earth’s unnatural warming can be blamed on the wealthiest 10%. But before you start looking elsewhere, remember that the income threshold for the top 10% around the world is only about $48,400 (€42,980). The top 1%, responsible for about 20% of global heating, begins at $165,700 (€147,200).

From CNN, Chinese researchers seeking historical data on the former range of the critically endangered Yangtze finless porpoise turned to ancient poetry from the Tang through Qing dynasties. They found, by geolocating the poets’ observations, that the porpoise has lost 65% of its range, largely in the last century.

You do such important work, Jason, so much heavy lifting. I'm grateful and have some idea of what it costs you, energetically to carry this burden and transform it into, sometimes, ...poetry.

Thank you for understanding the warp and woof of information, and then weaving it into these thoughtful, informative essays. I am in your debt.

Another wonderful essay. This is something I've never really considered before, though I often find myself trying to imagine what the natural world was like and what the air felt like to breathe, in distant times. I couldn't agree more about this kind of education being necessary for everyone. I spent a long year trying to get an outdoor education program started at my kids' school, and in the end had to give it up, after feeling like I was banging my head against the wall over and over again. I don't think most of our institutions are capable of caring (what would it mean for an institution to care??!) and even individuals who could have made different decisions seemed uninterested in the problem we were trying to address. Another vicious circle - because we don't have that education, we don't care, and because we don't care, we don't get that education. I guess we just have to be determined about it. Maybe I need to try again...