Hello everyone:

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read some curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

I want to start today by stating a few truths about the world we inhabit:

Every living organism – humans too – relies on a community of species, and that community relies in turn on other communities.

Little things run the world.

Life, by its nature, is conducive to life.

We were reminded of the first truth recently, in the final public words of biologist and whale researcher Roger Payne. The second we can attribute to the great E.O. Wilson, a child of Alabama, ant specialist, Harvard professor, and one of the most vital ecological voices of the last century. And the third, as I described last week, is one of Janine Benyus’s guiding principles of biomimicry, the study and application of life’s genius to human affairs.

So, what creatures come to mind for you when thinking about all three truths? Something small, something woven into multiple layers of ecological relationship, and something providing clear benefits to the living world around it. Caterpillars are a good choice, as are certain fungi or ants or bees. Because life is interwoven and conducive to life, there are millions of possible answers, I think. But here’s one you might not be considering: the freshwater mussel.

The humble mussel is an astonishing creature. Mussels clean lakes, ponds, and rivers; many of them have bizarre strategies to hijack fish for reproduction; and some live as long as humans, or longer. But let’s start with the wonderfully descriptive names we’ve given them here in the U.S.: Appalachian elktoe, Carolina heelsplitter, Georgia pigtoe, fuzzy pigtoe, pistolgrip, snuffbox, sugarspoon, fat pocketbook, purple wartyback, winged spike, fluted elephant ear, spectaclecase, rough rabbitsfoot, orangefoot pimpleback, sheepnose, slabside pearlymussel, fluted kidneyshell, and fatmucket, to name a few.

You can see the attentive folk etymology in these names. Wherever our language has been attentive, our culture once was too. Mussels were food for people, of course, which means we paid attention to shape (sugarspoon, elktoe, sheepnose), size (elephant ear), and color and texture (orangefoot pimpleback). And the diversity of names mirrors the incredible diversity of mussels, which is owed in part to the scale and intricacy of the Mississippi, Tennessee, and Ohio river systems that created innumerable places for mussels to evolve separately.

It’s important to note here that when I talk about American mussels, really I’m talking about the U.S. southeast, where freshwater animal species biodiversity (mussels, fish, crayfish, dragonflies, etc.) exceeds any other temperate region on Earth and rivals that of tropical regions. North America is home to around 300 mussel species; the southeast U.S. has about 270 of them. Alabama, in particular, is an epicenter of freshwater diversity. As the Center for Biological Diversity explains, “In its mere 190 miles, for example, [Alabama’s] Cahaba River harbors 125 species of fish, 50 species of mussel and 15 species of crayfish.”

Mussels are bivalves, animals that live within a hinged pair of shells. They feed by filtration, and in feeding provide an invaluable service for water clarity and quality. Each mussel filters up to 15 gallons of water per day, removing bacteria, algae, sediment, etc. Where mussels form large colonies known as shoals (or beds or reefs) they act like a Brita filter, sending clean water downstream. Thus the nickname, “the liver of the river.”

With all their filtering mussels play a vital role cycling nutrients and energy through the living community. They enrich the sediment around them with their excretions, helping aquatic plants to grow and increasing the populations of insect larvae, crustaceans, and other detritus feeders.

It’s not hard, then, to see how important mussels are for whole communities of life within and around the water, for the insects, plants, fish, amphibians, birds, and mammals whose lives radiate through and far beyond the quiet and essential working of these keystone species.

As the Center for Biological Diversity explained it in a document titled “The Southeast Freshwater Extinction Crisis,”

All Southeast aquatic species are intricately interconnected. For example, the map turtles' survival depends on the abundance of snails and mussels, which they eat, while mussels depend on fish to host their larvae — and the fish, in turn, depend on the abundance of flies, whose larvae they consume.

Mussels are part of the community that sustains us too. As a biologist with American Rivers told Inside Climate News,

To an everyday person who doesn’t know what a mussel is, who never wants to know what a mussel is, a mussel is helping them out and it’s making their water cleaner… We need them as part of our complex ecosystem.

Mussels are also reliable indicators of clean water. Because they’re incredibly sensitive to pollutants (including ammonia, chloride, potassium, sulfate, copper, nickel, and zinc), the presence of mussels indicates good overall water quality, including healthy sediments and stable fish populations. Without toxic human interference, in fact, mussels live about as long as we do: about 60-70 years, and occasionally as long as 100 years.

But of course, we are interfering with the lives of mussels – and the innumerable lives that rely on them – in very dramatic ways. They are vital, but they are disappearing. Frequently described as “one of the most imperiled groups of animals in the world,” more than a third of the 300 North American mussel species are extinct or in danger of extinction, with over 75% of remaining species listed as Endangered, Threatened, or of Special Concern.

A map of the threats to freshwater mussels is a map of the Anthropocene. They include invasive species, climate change, pollutants, stormwater runoff, road salt, and habitat loss due to dams. That’s a long and difficult list, but dams are likely the biggest killer. River mussels like shallow moving water, but dams radically alter water flow, sometimes leaving mussels high and dry, sometimes drowning them in warm and stagnant ponds, and sometimes releasing such intense floods that mussels are washed downstream. Worse, dams often block the movement of the fish mussels require for their reproduction. No fish, no mussels.

Why are fish necessary for a bivalve’s reproduction? This is where the story of freshwater mussels gets frisky and funky. Male mussels release sperm into the water; females draw it in to fertilize their eggs internally. A female will host several thousand at a time in her gills until they become glochidia, the larval stage. This is when things get interesting.

Mussels move very little, but need their young to spread far and wide. If lake or pond mussels simply expelled their larvae, they’d never leave home. If river mussels relied on currents, the young would all go downstream. Thus, mussels have evolved strategies, some of them incredibly wonderful, to hijack fish as larval transport. (Really, though, it’s payment for cleaning the fish’s habitat.)

Some mussel species – the boring ones – simply release free-floating larvae which must latch on to the gills of passing fish. Many others, though, have evolved elaborate lures that draw the fish (usually very specific species they’ve co-evolved with) in close. Some lures look like fish eggs or minnows. Some species actually trap the fish’s head inside the mussel’s shell. In all cases, the result is the female mussel blasting her nursery of glochidia into the fish’s mouth. The larvae pass through the gills and immediately clamp on, where they’ll stay for a short while feeding (days, weeks, sometimes months) before dropping off to start a life in new territory.

There’s so much more that’s fascinating about this, but I’ll let you learn it via a True Facts video by the brilliant, odd, and very funny Ze Frank. I hope you love it (and his other work) as much as Heather and I do:

I was also really happy to see this lovely comment below Ze Frank’s video:

I'm a freshwater mussel conservation biologist and I just want to thank you from the bottom of my heart for this video. It has been watched over one MILLION times in under three days and is almost certainly the most effective single piece of freshwater mussel outreach ever produced. I cannot clap loudly enough to express my thanks for creating it.

For the record, the video now has two million views.

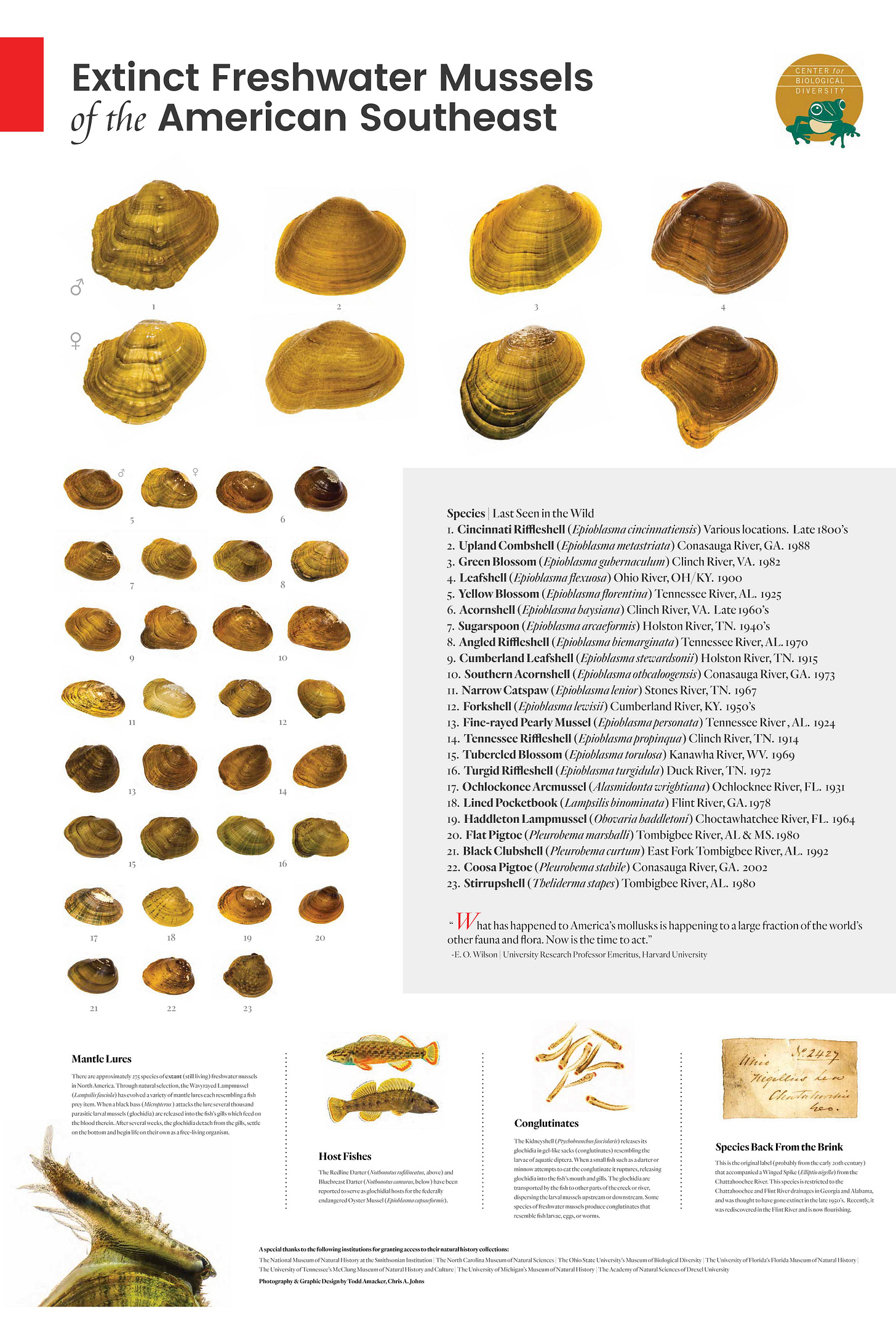

This young conservation biologist wasn’t merely cheering Ze Frank’s publicity for his little-known career. He was grateful that someone has drawn mass attention to one of the most imperiled groups of animals on Earth. “What has happened to America’s mollusks,” E.O. Wilson once said, “is happening to a large fraction of the world’s other fauna and flora. Now is the time to act.” Mussels, then, aren’t only endangered; they’re a symbol of how much can be lost, and how much we need to do.

The wonderful names we’ve bestowed upon mussels makes for an even sadder litany of extinctions. American rivers are now forever empty of the Cincinnati riffleshell, green blossom, narrow catspaw, Haddleton lampmussel, and the Coosa pigtoe, among many others.

What do we do to save mussels? Get a handle on climate change, for starters, before heat and intensified storms make their remaining habitat harder to inhabit. Better farming practices will reduce the contaminants and pollutants in rivers that fatally concentrate in these filter feeders. Smarter use of road salt and better stormwater runoff systems will help too.

But the biggest and most useful task for rescuing freshwater biodiversity is to tear down every unnecessary dam, especially in the southeastern U.S., which harbors 62% of the nation’s fish species, nearly half of North America’s dragonfly and damselfly species, and 91% of its freshwater mussels. Inside Climate News has an excellent story that covers the damage done to river habitat and the push to get rid of unnecessary dams. (American Rivers has set a goal to eliminate 30,000 dams by 2050, so you might consider giving them some support.)

Dams, wherever possible, must go. There are thousands and thousands that no longer serve any real purpose. And do we need river-killing hydroelectric dams in a world that can be powered by the sun and wind? Hydro power is actually looking like a bad bet in a climate-addled world. Federal and state policy should incentivize the removal of every one we possibly can, and set a high bar for justifying the existence of all the rest. (The Biden administration’s Infrastructure Bill does provide some funding for dam removal.) There are more than 91,000 dams in the U.S. alone. They’re large killing obstacles interfering with entire ecosystems. They are, to put it mildly, not conducive to life.

Alabama would be a great place to start. As I mentioned, Alabama is rife with freshwater biodiversity, but has 2,266 dams. (Next door, in Mississippi, there are 6,114 dams.) These dams have given the state the second highest number of extinctions (after Hawaii) in the country. And only Hawaii and California have more endangered or threatened species. Of Alabama’s 151 listed species, about 100 of them are freshwater, and 71 of those are mussels.

As a side note, the famed music production city of Muscle Shoals in Alabama owes its name to once-renowned mussel beds in the Tennessee River. The Cherokee before them had apparently given a similar name to the place. And for good reason; over 70 species of mussels once lived there. (Dams and other tragedies have reduced that diversity to fewer than 30 species.) I like that a city known for creating a great diversity of music out of its merging of musical traditions is named for one of the most diverse group of species in the region.

The Center for Biological Diversity is very actively working to protect southeastern freshwater habitat, and offers a good depth of information:

As just one example of a Southeast waterway in peril, [Alabama’s] Coosa River is the site of the greatest modern extinction event in North America, where 36 species went extinct following the construction of a series of dams. Overall the Mobile Basin is home to half of all the North American species that have gone extinct since European settlement.

You can check out a typical Center for Biological Diversity press release about their years-long efforts and successes in forcing the federal government to protect these endangered species. There’s probably no better organization to support in terms of dedication to mussel recovery.

For a geekier perspective, you can dig into the website for the Freshwater Mollusk Conservation Society. For my readers in the western and northwestern U.S., the Xerces Society is actively involved in studying and revitalizing mussel habitat in that region. Advocates for the health of Chesapeake Bay are working to protect mussel habitat in the upstream portions of the watershed. And lest you think this is only an American issue, a similar freshwater tragedy is playing out in Australia, as elsewhere in the world.

I’ll close by returning to the three truths I mentioned at the beginning:

Every living organism – humans too – relies on a community of species, and that community relies in turn on other communities.

Little things run the world.

Life, by its nature, is conducive to life.

The crises we face – transformed climate, transformed lands and rivers, transformed seas – are really only one crisis. Industrial civilization has displaced ecologies with economies at a planetary scale. There are many ways to describe how we got here and what our mistakes have been, but you could make a good start by noting that we’ve forgotten each of these three truths.

Industrial civilization has turned our ecological community into “resources” while deluding ourselves into thinking that we run the world, and only now do we seem to be realizing, at the policy level, the consequences of designing a world that is not conducive to life.

From the point of view of the mussels, we are the things we’ve designed and built. We are the life-killing dam, the road through the wetland, the excess nitrogen and phosphorus, the chainsaw and the earth-mover.

All of our wise talk now of tearing down dams, protecting half the Earth (E.O. Wilson), learning the language of whales (Roger Payne), designing society around natural principles (Janine Benyus), rewilding ecosystems, and restoring habitat for the little lives that run the world is really a conscious effort to no longer be those harmful things. And that’s beautiful.

Not as beautiful as a mussel – not yet – but on the right track.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

More efficient solar panels are on their way. From Mother Jones, a survey of the new tech and its impact on the shift to clean energy.

From Canary Media, a plan from the great folks at Rewiring America to get heat pumps in every American home by 2050. While you’re there, check out all the other great reporting from Canary Media on the clean energy revolution.

From Politico, did you know that small planes are still burning leaded gasoline? They’ve been exempted for decades because of pressure from the oil and gas industries. The FAA has only recently authorized the use of unleaded gas – though they’ve had opportunities to do so for years – but that replacement fuel isn’t being produced by refineries. Worse, lobbyists are pushing Congress to delay the transition for much longer. There is no safe amount of lead, and its impact on children near airports is well documented. Contact your congressional representatives to ensure that the 2023 FAA reauthorization bill does not include language to delay the transition to unleaded fuel.

From Inside Climate News, a clear and thorough assessment of what the radical recent increases in heat across this planet’s continents and oceans might mean. One answer, many scientists warn, is that we’ve reached tipping points in Earth systems that will accelerate the warming.

From George Monbiot at the Guardian, an op-ed praising the remarkable and comprehensive policy shift in France toward “an ecological civilization.” The steps France is taking might seem radical, but as Monbiot says, “they are the minimum policies that any responsible government should be implementing now, as our planetary emergency unfolds.” These include establishing a ministry for ecological transition, training all five and a half million French public sector workers on the principles of the transition, passing a comprehensive circular economy law to reduce waste, and pushing industry to make more durable products and to pay for the end-of-life processing and disposal of those products.

Also from the Guardian, after watching the recent trial in Montana, activists in more US states are looking to create constitutional rights to a healthy environment for their citizens, esp. as leverage to hold fossil fuel companies and policy-makers accountable for the impacts of climate change. Some of you will remember I’ve written about the Green Amendment movement before. If you’re unfamiliar, please look into it. It’s an elegant solution to a global problem.

A great interview with Bill McKibben by

at . One of the marvelous things about McKibben is that he can articulate so much about the state of the climate battle in just a few words. I don’t know if anyone else leading these conversations has his mix of pragmatism and grace.From the PRNewswire, Russia and China have again blocked efforts to create a huge and much-needed Marine Protected Area in Antarctic waters. This is terrible but unsurprising news. They’ve been blocking this effort since it was first proposed in 2010. But 2023 is the year that Antarctic sea ice has hit a radical new low, and we need new thinking for a new reality.

From the World Bank, “Detox Development: Repurposing Environmentally Harmful Subsidies,” a report on how to better spend the trillions of dollars governments spend to subsidize the worst behaviors in industries (fossil fuels, agriculture, fisheries, etc.) that are disrupting Earth’s natural systems. It should be the easiest, most rational decision we can make – like an addict choosing to spend their drug money on rehab instead – but these subsidies have been baked into politics and economies for so long that they seem untouchable.

Maybe it's the mussels in the water of you Maine writers.....but you and Sam and Kathleen are three of my favorite substack writers. This essay is a prime example of one of the reasons why. I know you get uncomfortable with praise, but tough luck, here's some anyway. This essay should be read by everybody. Everybody. Especially policymakers from local to national levels. That photo of the filtered water is unforgettable and a game changer. Who can see it without wanting to protect the creatures that did the filtering? Amazing essay!

This is an extraordinary essay and I love the video! I live near the Duck River in Middle Tennessee and have gotten to experience shoals and identifying many mussel species. Seeing the stores I've heard about "mussel sex" shown in such vivid detail in the video is unforgettable. And I agree with the other comment about the power of that photo re: water quality. Thanks for this great article!