Hello everyone:

This week I’m offering another throwback essay, a piece from two years ago that explores islands both real and metaphoric, and both beautiful and tragic. As with other republished essays, it has been updated and edited for the present moment.

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the post to read this week’s curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

If you’ve been reading the Field Guide from the early days, you’ll know that, among other things, I’m neither religious nor particularly fond of paint. And yet a couple years ago I found myself spending a few weeks scraping, priming, and painting the trim on a century-old church. (And reglazing nearly every inch of every window.) The church sits in the middle of a three-mile-long forested respite from civilization known today as Louds Island. With perhaps three dozen houses and no real roads or other infrastructure, the island hosts a small, scattered, summer population. The island is unoccupied in the winter.

It’s fair to say that the church needs a paint job more than the islanders need the church, though it is a beloved community center and a registered historical site. Like so much that is quiet and restorative and attentive to history in this world, the church is hard to find and no longer at the center of everyday life.

So why am I involved? Three reasons. One, I paint for extra income. Two, I love the island and the wild quietude of this island-dotted stretch of coast known as Muscongus Bay. And three, I wanted to spend time in the building because my family has a small connection to the sad, terrible, and tragic story that lies behind the founding of the church. It’s a story known to some as the Shame of Maine.

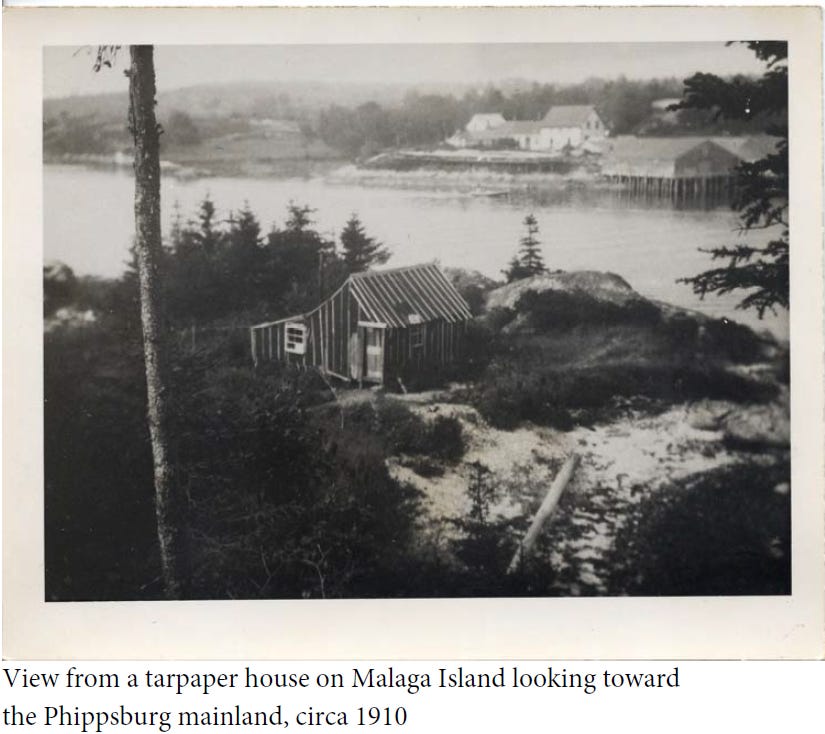

Much of the lumber used to build the church in 1913 came from a disassembled schoolhouse on another island over in Casco Bay. Two of my great-great-aunts, or perhaps one aunt and my great-grandmother – the details are fuzzy – spent a bit of their time teaching in that schoolhouse between its construction in 1906 and its dismantling in 1912. They lived at Ridley’s Landing, an old noble house and wharf that has been in my mother’s side of the family since my great-great-grandfather Frank Ridley bought it in the late 1800s, and which sits a mere 400 feet away from that island on the shore of Sebasco, a fishing village in the town of Phippsburg.

The island which bore the schoolhouse is called Malaga. It shields the lobster boats, fishing boats, and pleasure boats moored in Sebasco Harbor from the wind and waves of nearby open sea. Malaga is a small, 43-acre island, so close to the mainland as to be nearly an extension of it, yet at the turn of the last century Malaga was being held at arm’s length. Phippsburg did not want it. The cluster of fishing families living on it had, through no fault of their own, become notorious because of a confluence of several cruel forces: cultural isolation, wealth and real estate, racism and eugenics, and some sneering, hard-hearted media.

The story is too long to properly tell here, but here it is in brief.

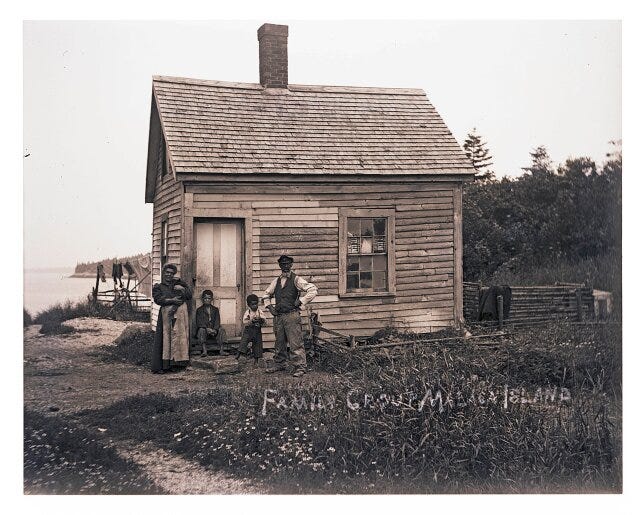

The Malaga community, some forty people as the 20th century dawned, was largely Black and mixed-race. This was, as you might imagine, a rare situation. Malaga was very poor, but so were nearly all the fishing communities perched on the stony outcrops of the Maine coast. Fishing wasn’t nearly as good as it had been, due to the overfishing of inshore waters - the early days of the Anthropocene - but like other Mainers the islanders lived, labored, and persisted. Racial intermarriage was illegal, but locals looked the other way because Malaga had been an occupied part of the Phippsburg community since the 1860s. Everyone on the island was a neighbor, and tied in various ways to the Sebasco community. Life was a struggle. A neighbor’s poverty and marriage wasn’t any of your business.

Until it was. Eventually, the racist noise of the outside world became too much. The eugenics movement – advocating for the editing of the human population based largely on racist principles – was considered by many (including the conservation movement) to be cutting-edge science and had swept the nation until it finally reached the Maine coast.

Wealthy vacationers from Boston and New York had discovered the coast as well, and were beginning to shape it according to their biases and wallets. Summer residents were building large houses and bringing the national zeitgeist north. The media paid attention to the culture clash and began circling Malaga like sharks around a sinking ship. Here’s a summary from a 2020 article in Bowdoin Magazine:

In the years after the island’s founding, hundreds of sensational accounts circulated about it, spreading claims of ignorance and contamination. A 1902 article from the Bath Enterprise, a local newspaper, condemned Malaga in the name of religious purism: “No worse heathenism we imagine could be found in far off heathen countries than can be found on this godless island.” Another article from the Casco Bay Breeze described the island as “the home of southern negro blood . . . [an] incongruous scene on a spot of natural beauty.” Word of Malaga spread south as mainlanders grew fixated on an island that they believed marred the state’s idyll. Without these “incongruous” outliers, Maine might be easier to sell to tourists; shipbuilding, the backbone of the regional economy, was dying, and a tourist economy beckoned. Perhaps, without the island’s residents, Malaga could be made into a resort.

One of the many insanities of racism – its foundational one being that there is such a thing as “race” – is that skin color has been associated with “low” morals and poverty. Given the brute cultural forces which restricted (and continue to restrict) communities of color from thriving, it’s the logic of someone judging how easily a person drowns even as they hold the victim’s head underwater.

Phippsburg, wanting neither the reputation by association nor the costs of care, argued in court that Malaga belonged to the town of Harpswell. The state disagreed, but then took ownership itself. There was a resort to build, they said. At the governor’s direction, the state quickly moved to uproot the Malaga community. Through the usual colonial ploys of false ownership claims and state-sponsored aggression, residents were given little choice but to leave, as this description from the Maine State Museum (which hosted an excellent Malaga exhibit some years ago) makes clear:

Residents were told they must vacate the island by July 1, 1912. No alternative homes were provided or suggested, but when Agent Pease arrived on Malaga Island on July 1st, he found all the houses were gone – dismantled and removed by the residents themselves. To complete the eviction, the state exhumed the cemetery remains on Malaga Island, combining seventeen individuals into five caskets, and moved them to the cemetery at the Maine School for the Feeble Minded.

That final detail, the brute exhuming of the community’s graves and lumping them together in a handful of caskets, has always haunted me. Though perhaps I should be far more disturbed by the state’s decision to move a small group of residents deemed unfit for society to the School for the Feeble Minded, where they lived out their days in misery and isolation before joining their ancestors in the institution’s graveyard. The rest of the community melted into Phippsburg and Harpswell, some of them rafting their entire houses to places along the shore where they wouldn’t be haunted or hunted.

A century later I was at a restaurant not far away and saw a cheerful, colorful poster of lobster pot buoys (historical and current) from Harpswell, each identified by their owner. It’s the kind of thing a seasonal resident might buy to decorate their summer cottage, without knowing the history on display. I spent some time looking for names I might recognize, then suddenly caught my breath: One fellow who I was sure had been part of a Malaga family had painted his buoy half black and half white.

A well-told children’s novel that captures a piece of the Malaga tale is Lizzie Bright and the Buckminster Boy, and a more thorough history of the Malaga story can be found on the Maine Coast Heritage Trust site. MCHT, a conservation group, now preserves the island, which never saw another home built upon it, much less a resort, and which has long ago reverted back to spruce forest. You can take a boat to Malaga, read about the families and the community, and walk the short trail that circles the island.

For generations, a sense of shame lingered with those sent into exile, and with their descendants, while those who sent them simply pretended the crime never happened. It was a story “better left untold,” until finally the truth became public a century later. Two recent Maine governors, recognizing where the shame lies, have apologized to the descendants and the ghosts.

It was difficult for me to conjure up all this suffering as I sat at the kitchen table in the Louds church built of the Malaga school lumber. The island is a very peaceful place, and the church (in this historical instance) had nothing to do with the violence against those poor people. My days have consisted of long hours on the ladders, and lovely evening hours walking the dirt roads and granite shores.

That said, I have long wondered what my great-grandmother and her siblings thought about the erasure of the community a stone’s throw away from their wharf. (See the picture above to understand how close they were.) The lives of the Malagaites were very much woven into theirs. I’ve heard through my family that my great-great-grandfather Frank Ridley, who ran a store from the house, was more likely to provide goods on credit to the Malaga folks than he was to call in those debts. My mother told me that she’d heard that his daughters, aside from doing a bit of teaching in the school, had also gone over at least once to help a family that had fallen sick.

My mother spent much of her childhood looking across the harbor at Malaga, but for nearly all of it never heard a word about the expulsion, other than her great-uncle Mel, who was kin to one of the families and who had offered his boat to help some of the folks move off the island, once or twice shaking his head and saying, “Those poor bastards.” (“Bastards” in this usage wasn’t an insult, but a sign of empathy.)

And now here I was, kin to the folks at Ridley’s Landing, with my hands on the Malaga lumber shipped from that island to this one 109 years earlier. My role was to scrape off the old paint and to begin anew. Whether this is a metaphor for attending to the past or obliterating it I cannot decide.

My relationship with the history did grow through other means while living in the church. I learned more about the acquisition of the schoolhouse after rummaging around in the papers in the church desk (let’s be charitable and call this “research”).

Louds Island was a thriving (white) farming and fishing community at the turn of the century, but it had no church. The Louds Island Church Society formed in July of 1912 – coincidentally or strategically at exactly the deadline for the Malaga expulsion – and a year later the cornerstone was being laid, after the Society agreed to accept the gift of the school from the state and after seven island men sailed in the schooner Abner Keene to Malaga to dismantle and remove the last trace of the Malaga community.

I am struck, finally, by the islands we make and the island-making forced upon us: the wealthy in private schools and gated communities, the poor in flood zones and food deserts and industrial zones and roadside trailers. The devouring that characterizes the Anthropocene has largely been driven by the machinery of capitalism and colonialism, which with their ideas that the world is a list of resources and that ownership is the soul of civilization have been extraordinarily cruel to anything or anyone deemed a resource worth owning.

Race is one of those half-witted prejudices – what Freud called “the narcissism of minor differences” – that have forever characterized human squabbles and suspicions between neighbors, tribes, and villages, but within the continent-sweeping forces of the modern world minor differences become leverage in the hands of those with unchecked power who own much and wish to own more. What is chattel slavery but the ultimate expression of capitalism’s degradation of human life for the purpose of turning a profit? Find me a place or time in the last few centuries in which the poor have been anything more than resources to be plundered, and I’ll thank you for pointing to an island of peace amid a sea of trouble.

I’m reminded of Pope Francis’ remarkable 184-page, 37,000-word encyclical on the environment, Laudato Si’, in which he describes the Earth as a

sister [who] cries out to us because of the harm we have inflicted on her by our irresponsible use and abuse of the goods with which God has endowed her. We have come to see ourselves as her lords and masters, entitled to plunder her at will… This is why the earth herself, burdened and laid waste, is among the most abandoned and maltreated of our poor.

Francis makes an extraordinarily important Anthropocene metaphor here: the planet is our kin, impoverished and abused.

The name of Louds Island is derived from an early settler family. Its proper name, though, is the one given to it for millennia by the Wabanaki: Muscongus, meaning “fishing place.” Muscongus is a good name, if slower off the tongue. I’ve tried to use it more often, but in this busy life it’s always so much easier to be quick and loud.

Amid the noise and tragedy of the Anthropocene, it’s a remarkable privilege to work and play on the island. Just as my great-great-aunts could leave the Malaga schoolhouse and row across the harbor one last time and then spend the remainder of their days watching the spruce slowly grow up where the homes and graves and children once stood, I’m safely at play with words and ideas about a history where once there was only shame and pain and lives turned upside down.

Still, though, we must all make islands for respite during this struggle to slow and eventually reverse the pace of intensified Anthropocene transformation. Climate change, ocean acidification, population growth, industrial/chemical agriculture, and so much more are doing to communities of life what the state of Maine did to the folks of Malaga. As I’ve written before, there’s no place to hide from this process – we’re ensnared and thus both innocent and culpable – and so we have to make our uneasy peace within it, for our own sanity, even as we fight it. There are no more Edens, but there are places of respite. Islands, if you will. Muscongus is that kind of place for me, and I’m grateful for every opportunity to explore it.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

If you read nothing else here, read this: From the Tyee, “Wildfires, Grief, and Paralysis,” a beautifully and powerfully written article on what the widespread, raging fires in Canadian forests tell us about who we are and what we’ve done. It’s honest, heartbreaking, and necessary writing.

From

at , a lovely and important essay on how Kamala Harris’ choice of Tim Walz for vice president might be a great long-term benefit for fighting climate change. Walz is a neighborly guy, one who can build political bridges, and may serve as a model as we move deeper into an era in which neighbors helping neighbors will be increasingly important.From the

, another massive and extraordinary set of investigative reports on China’s fishing practices. This new work focuses on how China has found a new way to extract resources from other nations’ restricted territorial waters. Rather than using force or subterfuge, China’s fleets are now “flagging into” national waters in nations in Africa, Asia, and South America by buying the right to register their ships in those countries.From Mongabay, one of the most frightening things in the world right now that isn’t either climate change or U.S. politics: the raging spread of bird flu through avian and mammalian populations around the globe. The article is titled Animal Apocalypse for good reason. Please read it; this is a story that isn’t being told enough.

From the Times, some excellent news (I think) on the story of deep sea mining. There’s been an important change of leadership at the tiny U.N.-affiliated agency tasked with overseeing and regulating deep sea mining. A Brazilian environmental regulator has replaced a British lawyer long thought to be far too cozy with mining interests. This story comes on the heels of another (astonishing) scientific discovery, that the polymetallic nodules sought by mining companies are actually producing oxygen for deep sea ecosystems. We’re closer now than I could have hoped to pressing pause on this terrible idea.

Also from the Times, a follow-up to my essay last week on our relationships with animals: an op-ed that brilliantly explores the extreme differences between how we treat dogs and pigs. (Thanks to Bryan Pfeiffer of

for the link.)From Reasons to be Cheerful, a good-news story about a man on a mission to plug orphaned oil wells around the U.S. There are perhaps two million abandoned wells around the country, with at least 126,000 of them “orphaned,” meaning the ownership is unknown. They leak an extraordinary amount of methane, a powerful greenhouse gas. There is no good reason these wells aren’t plugged, only the reasons that accompany the power and privilege of the fossil fuel industry. Read the article, and check out the website of the man and his nonprofit: The Well Done Foundation. Support them if you can.

Want to know what the climate will feel like in 60 years in your city? Check out the interactive map at CityApp from the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science. For example, under a high emissions scenario, Buffalo, NY, will have a climate similar to southern Illinois. Portland, ME, will be like western Kentucky. San Francisco becomes Tijuana, Mexico. In Europe, Paris becomes like central Italy, and Prague resembles central Bulgaria.

From NJ Spotlight News, good news on the fate of horseshoe crabs. These ancient creatures have long been collected and had their blood drained for use in drug testing by the pharmaceutical industry. The industry is now allowed to use synthetic chemicals (already common in Europe) rather than the product derived from horseshoe crabs. The rule is voluntary, but public pressure should help in reducing the harmful practice. And as with all things ecological, there are other benefits. The reduced pressure on horseshoe crabs will benefit migrating shorebirds who feed on the crab eggs.

And from Anthropocene, something we should have known but probably already suspected: Artificial sweeteners don’t break down in our bodies, nor in the aquatic environments they end up in. Of course this seems to make them a problem for microbial life, which in lab tests seemed to surge and then crash in response to being dosed by this terrible stuff.

As ever, so beautifully written with such gentleness and grace. So comforting in these times of global uncertainty & political unrest.

We just can't help ourselves. We want to distinguish "the other". We want to maximize our own tribe's success. We want to reproduce our kind- to feed our families, to do anything to ensure their survival. We are forced by our nature to sometimes be selfish, to be cruel to the other- human or animal in order to survive. We cannot afford to be softhearted, invariably compassionate, putting others first- those are not survival traits. We are clever but not farsighted..we seldom look more than handful of years into the future, hence our actions often prove reckless and destructive. The Anthropocene is our measure and creation. We are the ones who set the banquet table for ourselves and all other species and now all must sit down to eat the bitter portions.