Hello everyone:

My work on a quiet, lovely Maine island has taken longer than I planned. I didn’t realize how big a job it was and so have been out there for nearly all the days I would ordinarily be chipping away at this week’s writing. I’m home only for a couple days before heading back out to the island and am writing this essay at the last minute. I do have cell reception on the island, but am happily living a stripped-down, off-grid life in a very, very quiet place, and I hope you’ll forgive me for a) taking walks after 10-hour work days rather than writing, and b) not trying to produce a longer, heavily-researched essay with my thumbs.

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the post to read this week’s curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

If you’ve been reading the Field Guide from the early days, you’ll know that, among other things, I’m not motivated by religion and not particularly fond of paint. And yet for the last week and a half I’ve been scraping, priming, and painting the trim on a century-old church. (And reglazing nearly every inch of every window.) The church sits in the middle of a three-mile-long forested respite from civilization known as Louds Island. With perhaps three dozen houses and no real roads or other infrastructure, the island hosts a vanishingly small, scattered, seasonal population. Those few congregants are summer residents of Louds, which is unoccupied in the winter. It’s fair to say that the church needs a paint job more than the islanders need the church, though it is a beloved community center and a registered historical site. Like so much that is quiet and restorative and attentive to history in this world, the church is hard to find and rarely at the center of anyone’s life.

So why am I involved? Three reasons. One, I paint for extra income. Two, I love the island and its place in the wild quietude of this island-dotted stretch of coast known as Muscongus Bay. And three, I wanted to spend time in the building because my family has a small connection to the sad, terrible, and tragic story that lies behind the founding of the church. It’s a story known to some as the Shame of Maine.

Much of the lumber used to build the church in 1913 came from a disassembled schoolhouse on another island over in Casco Bay. Two of my great-great-aunts, or perhaps one aunt and my great-grandmother – the details are fuzzy – spent a bit of their time teaching in that schoolhouse between its construction in 1906 and its dismantling in 1912. They lived at what’s known now as Ridley’s Landing, an old noble house and wharf that has been in my mother’s side of the family since my great-great-grandfather Frank Ridley bought it in the late 1800s, and which sits a mere 400 feet away from that island on the shore of Sebasco, a fishing village in the town of Phippsburg.

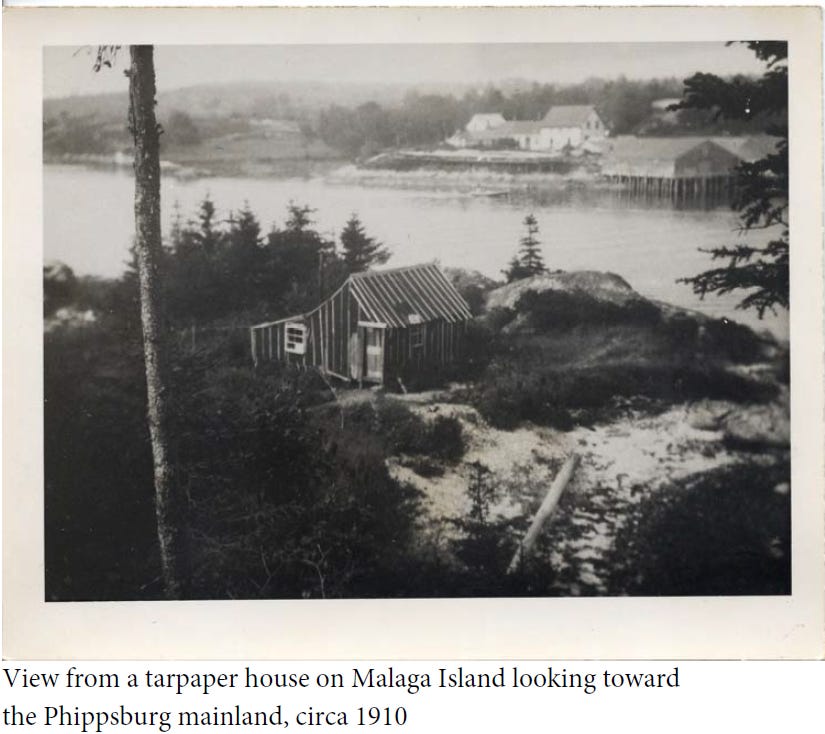

The island which bore the schoolhouse is called Malaga. It shields the lobster boats, fishing boats, and pleasure boats moored in Sebasco Harbor from the wind and waves of nearby open sea. Malaga is a small, 43-acre island, so close to the mainland as to be nearly an extension of it, yet at the turn of the last century Malaga was being held at arm’s length. Phippsburg did not want it. The cluster of fishing families living on it had, through no fault of their own, become notorious because of a confluence of several cruel forces: cultural isolation, wealth and real estate, racism and eugenics, and some sneering, hard-hearted media.

The story is too long to properly tell here, but here it is in brief. The Malaga community, some forty people as the 20th century dawned, was largely Black and mixed-race. This was, as you might imagine, a rare situation. Malaga was very poor, but so were many of the fishing communities perched on the stony outcrops of the Maine coast. Fishing wasn’t nearly as good as it had been, due to the overfishing of inshore waters, but the islanders lived, labored, and persisted. Racial intermarriage was illegal, but locals looked the other way because Malaga had been an occupied part of the Phippsburg community since the 1860s. Everyone on the island was neighbor and a Mainer. Everyone was living on the edge, and somebody else’s poverty and marriage weren’t any of your business.

Until it was. Eventually, the racist noise of the outside world became too much. The eugenics movement – advocating for the editing of the human population based largely on racist principles – was considered by many (including the conservation movement) to be cutting-edge science and had swept the nation until it finally reached the Maine coast. Wealthy folks from Boston and New York had discovered the coast as well, and were beginning to shape it according to their biases and wallets. Here’s a summary from a 2020 article for Bowdoin Magazine:

In the years after the island’s founding, hundreds of sensational accounts circulated about it, spreading claims of ignorance and contamination. A 1902 article from the Bath Enterprise, a local newspaper, condemned Malaga in the name of religious purism: “No worse heathenism we imagine could be found in far off heathen countries than can be found on this godless island.” Another article from the Casco Bay Breeze described the island as “the home of southern negro blood . . . [an] incongruous scene on a spot of natural beauty.” Word of Malaga spread south as mainlanders grew fixated on an island that they believed marred the state’s idyll. Without these “incongruous” outliers, Maine might be easier to sell to tourists; shipbuilding, the backbone of the regional economy, was dying, and a tourist economy beckoned. Perhaps, without the island’s residents, Malaga could be made into a resort.

One of the many insanities of racism – its foundational one being that there is such a thing as “race” – is that skin color has been associated with “low” morals and poverty. Given the brute cultural forces which restricted (and continue to restrict) communities of color from thriving, it’s the logic of someone judging how easily a person drowns even as they hold the victim’s head underwater.

Phippsburg argued in court that Malaga belonged to the town of Harpswell. The state disagreed, but then took ownership itself, and at the governor’s direction quickly moved to destroy the Malaga community. Through the usual colonial ploys of false ownership claims and state-sponsored aggression, residents were given little choice, as this description from the Maine State Museum (which hosted an excellent Malaga exhibit some years ago) makes clear:

Residents were told they must vacate the island by July 1, 1912. No alternative homes were provided or suggested, but when Agent Pease arrived on Malaga Island on July 1st, he found all the houses were gone – dismantled and removed by the residents themselves. To complete the eviction, the state exhumed the cemetery remains on Malaga Island, combining seventeen individuals into five caskets, and moved them to the cemetery at the Maine School for the Feeble Minded.

That final detail, the brute exhuming of the community’s graves and lumping them together in a handful of caskets, has always haunted me. Though perhaps I should be far more haunted by the small group of residents who had previously been deemed unfit for society and sent to the School for the Feeble Minded to live out their days in misery and isolation.

The rest of the community melted into Phippsburg and Harpswell, some of them rafting their entire houses to a spot where they wouldn’t be haunted or hunted. A century later I was at a restaurant not far away and saw a cheerful, colorful poster of lobster pot buoys (historical and current) from Harpswell, each identified by their owner. One name I recognized as part of a Malaga family had painted his buoy half black and half white.

A well-told children’s novel that captures a piece of the Malaga tale is Lizzie Bright and the Buckminster Boy, and a more thorough history of the Malaga story can be found on the Maine Coast Heritage Trust site. MCHT, a conservation group, now preserves the island, which never saw another home built upon it, much less a resort, and which has long ago reverted back to spruce forest. The shame lingered with those sent into exile, and with those who sent them. It was a story “better left untold,” until finally the truth became public a century later. Two recent governors have apologized to the descendants and the ghosts.

It has been difficult for me to conjure up all this suffering as I sat at the kitchen table in the Louds church built of the Malaga school lumber. It’s a peaceful place, and the church (in this historical instance) had nothing to do with the violence against those poor people of color. My days have consisted of long hours on the ladders, and lovely evening hours walking the dirt roads and granite shores. That said, I have long wondered what my great-grandmother and her siblings (and their Sebasco neighbors) thought about the erasure of the community a stone’s throw away from their wharf. The lives of the Malagaites were very much woven into theirs. I’ve heard through the family that my great-great-grandfather Frank Ridley, who ran a store from the house, was more likely to provide goods on credit to the Malaga folks than he was to call in those debts. My mother told me that his daughters, aside from doing a bit of teaching in the school, had also gone over at least once to help a family that had fallen sick.

My mother spent much of her childhood looking across the harbor at Malaga and for nearly all of it never heard a word about the expulsion, other than her great-uncle Mel, who was kin to one of the families and who had offered his boat to help some of the folks move off the island, once or twice shaking his head and saying, “Those poor bastards.”

My role at this moment in the life of the Malaga lumber shipped from that island to this one over a century ago is to scrape off the old and to begin anew. Whether this is a metaphor for attending to the past or obliterating it I cannot decide.

I do know a little more about the acquisition of the schoolhouse, however, after rummaging around in the papers in the church desk. Louds Island was a thriving (white) farming and fishing community at the turn of the century, but it had no church. The Louds Island Church Society formed in July of 1912 – coincidentally or strategically at exactly the deadline for the Malaga expulsion – and a year later the cornerstone was being laid, after the Society agreed to accept the gift of the school from the state and after seven island men sailed in the schooner Abner Keene to Malaga to dismantle and remove the last trace of the Malaga community.

I am struck, finally, by the islands we make and the island-making forced upon us: the wealthy in private schools and gated communities, the poor in flood zones and food deserts and industrial zones and roadside trailers. The devouring that characterizes the Anthropocene has largely been driven by the machinery of capitalism and colonialism, which with their ideas that the world is a list of resources and that ownership is the soul of civilization have been extraordinarily cruel to anything or anyone deemed a resource worth owning.

Race is one of those half-witted prejudices – what Freud called “the narcissism of minor differences” – that have forever characterized human squabbles and suspicions between neighbors, tribes, and villages, but within the continent-sweeping forces of the modern world minor differences become unchecked power in the hands of those who own much and wish to own more. What is chattel slavery but the ultimate expression of capitalism’s degradation of human life for the purpose of turning a profit? Find me a place or time in the last few centuries in which the poor have been anything more than resources to be plundered, and I’ll thank you for pointing to an island of peace amid a sea of trouble.

I’m reminded of Pope Francis’ recent remarkable 184-page, 37,000-word encyclical on the environment, Laudato Si’, in which he describes the Earth as a

sister [who] cries out to us because of the harm we have inflicted on her by our irresponsible use and abuse of the goods with which God has endowed her. We have come to see ourselves as her lords and masters, entitled to plunder her at will… This is why the earth herself, burdened and laid waste, is among the most abandoned and maltreated of our poor.

For a recent incarnation of this simultaneous destruction of planetary and human community, look no further than the recent set of excellent Mother Jones investigative reports on private equity sucking the lifeblood out of society. Here again is uncontrolled capitalism generating profits by devaluing, if not devastating, all of us who need healthcare and daycare and journalism and so much more.

The proper name of Louds Island, derived from an early settler family, is the name given to it for millennia by the Wabanaki: Muscongus, meaning “fishing place.” Muscongus is a good name, if slower off the tongue. I’ve tried to use it more often, but it’s always so much easier to be quick and loud. Amid the noise and tragedy of the Anthropocene, it’s a remarkable privilege to work and play out here. Just as my great-great-aunts could leave the Malaga schoolhouse and row across the harbor one last time and then spend the remainder of their days watching the spruce slowly grow up where the homes and graves and children once stood, I’m safely at play with words and ideas about a history where once there was only shame and pain and lives turned upside down.

Still, though, we must all make islands for respite during this struggle to slow and eventually reverse the pace of intensified Anthropocene transformation. Climate change, ocean acidification, population growth, chemical-based agriculture, and so much more are doing to communities of life what the state of Maine did to the folks of Malaga. As I’ve written before, there’s no place to hide from this process – we’re ensnared and thus both innocent and culpable – and so we have to make our uneasy peace within it, for our own sanity, even as we fight it. There are no more Edens, but there are places of respite. Islands, if you will. Muscongus is that kind of place for me, and I’m grateful to the people who have invited me out to explore it.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

From Vox: A plea to stop telling kids that climate change means they have no future:

Also from Vox, an explanation of the Biden administration’s recent use of the Defense Production Act to increase activity in the clean energy sector (heat pumps, solar, etc.):

From the New Yorker, a long, complex, beautiful rumination on what the commons (as in “the tragedy of the commons”) was and wasn’t, and what remains of it in this world:

From Yale e360, a “beyond magical thinking” reality check from energy scientist Vaclav Smil, who says “I am neither a pessimist nor an optimist. I am a scientist trying to explain how the world really works.” Smil criticizes not only the worlds’ lack of progress in reducing emissions but also what he calls our habit of bouncing between announcing catastrophes and promoting techno-utopian solutions. What we need, he says, is a rational analysis. There are plenty of other people who make this point every day, but because of his expertise in energy matters his essay is well worth reading anyway.

From The Revelator, an interview with Laura J. Martin about her book Wild By Design, a history of ecological restoration. We are actively working across the planet to undo the harm that we’ve caused, and that’s a reason for celebration and inspiration. But how we got here and where we’re going are fascinating.

This is your next book Jason. this under-reported (outside of Maine) story must be told. You write so eloquently about this history, and your own family's connection.

Nice view of Dutch and Sals house from the island .. lots of good memories