Hello everyone:

As a sort of follow-up to my recent essay, “We Are Not Alone,” I was thinking about how it might overlap with the trauma that’s overtaken U.S. governance. The phrase “the politics of loneliness” came to mind as I was doing the dishes. This week’s essay is an exploration of that phrase.

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read some curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

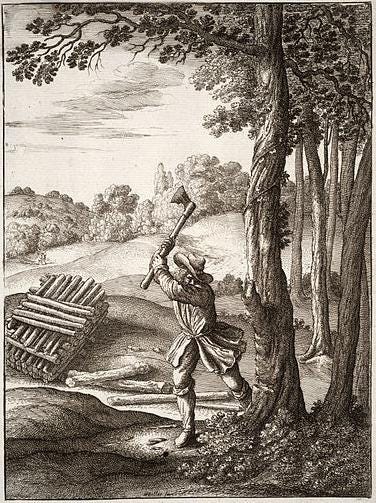

1. Woodcutter culture

Here’s a proverb for the moment:

The forest was shrinking but the trees kept voting for the axe, for the axe was clever and convinced the trees that because his handle was made of wood, he was one of them.

This is not the original version. It’s been rewritten and plumped up for this talkative age, turning the brevity of the ~2600-year-old original (“When the axe came into the forest, the trees said The handle is one of us”) into a Twitter-ready political meme. The proverb’s origin is unclear - maybe from Aesop, perhaps Turkish - but I think that uncertainty reflects its universality across cultures and centuries. Forests have been bemoaning the irony of axe handles for a very long time, longer even than voters have been voting against their self-interest and better angels.

Here’s how I see it. Voter or politician, the stories in our head are always less real than the reality they describe. Yet we are in thrall to stories. In fact, we cannot live without them, as desperate for narrative as we are for food, water, and shelter.

Every species but ours exists successfully without the lifelong training wheels we think of as our special consciousness. Humans are constantly reciting stories about other humans, because unlike Red Wolves, White Admiral butterflies, or Blue Oaks, we don’t know how to live. So we communicate incessantly to create maps, signs, and guardrails to guide us. We form cultures with networks and hierarchies to structure the messaging.

The problem, of course, is that we act as if there are no objective, permanent maps and guardrails for the people who make the maps and guardrails. Every culture invents and reinvents itself. Every culture rises and falls. Science, our best attempt at objectivity, is still just an advisor to culture rather than its foundation. Facts, in a world of talkative apes, are just another story.

Untethered as we’ve become from the shared reality of moths and manatees, we have only our collective memory and imagination to guide us. But the memory-keepers and storytellers we choose matter. Unfortunately, elections are a truly poor method for reliably choosing someone wise enough to shape the narrative. John Steinbeck explained in Cannery Row why, in this profit-driven culture, we so often vote for the wrong people:

The things we admire in men, kindness and generosity, openness, honesty, understanding and feeling are the concomitants of failure in our system. And those traits we detest, sharpness, greed, acquisitiveness, meanness, egotism, and self-interest are the traits of success. And while men admire the quality of the first, they love the produce of the second.

This is one feature of the politics of loneliness: Too many voters look up hopefully to whoever has fought and bought their way to the pedestal, aspiring to their success from the wage-slavery that an endless line of those leaders has maintained. In our stories, a branch may dream of being an axe handle, but only if it has been told that eating sunlight for the benefit of everyone is less useful than moving fast and breaking things.

As this crucial moment in both human and Earth history demonstrates, it’s easy to lose our way - or even crash and burn - and not know it.

More and more, in our boxed-in, digitized, ecologically isolated lives, we seem to exist in our own worlds rather than the real world. Much of what ails us now is rooted in the delusion that our mind is separate from our body, that our body is not an animal, that other animals and plants are hollow machines, and that the entire thriving Earth is a warehouse that belongs to us. Or as Gregory Bateson so elegantly put it,

The major problems in the world are the result of the differences between how nature works and the way people think.

You and I know better, and on some level so do most people. We feel the integration of mind and body, we see the soulful sparks in our pets and in wild animals, we learn that plants are more consciously complex than corporations, and - if we’re paying any attention at all - we realize that we belong to the Earth. But somehow, still, our global woodcutter culture does not know or reflect this.

And we have little choice but to participate, at least partly, in the false narrative. There are forces it has engendered and empowered - businesses and banks too big to fail, fascists and religious extremists too blind to see, and billionaires too selfish to care - and those forces are telling us, the trees, that what is good for them is good for us, despite the wood chips at our feet.

2. Be the advanced alien race you want to see in the universe

The good news is that our irrational social instincts can be constrained by any culture wise enough to insist upon mutual respect both among ourselves and between us and the living world. We need to be taught from an early age to treat the Earth as sacred, to love thy neighbor, and to aspire to empathy as the highest form of intelligence. We have plenty of maps, both new and old, to guide us.

And I should note that even in the Anthropocene, despite the suffering that has characterized much of human existence and which haunts many of us still, life for the average person has improved substantially in the last two centuries. As the charts in the graphic below show, our stuttering attempts at respect-based democratic governance have grown and spread at the same time that basic needs have increasingly been met. These charts are not a portrait of flourishing, but they show a reduction in misery, and in this culture that’s a measure of success.

The bad news is that these benefits for our fellow humans have come at an existential cost to life on Earth. If you fear the global implications of the fascist bludgeon taking shape in the White House and across the U.S. federal government - and you definitely should - remember that the natural world has been bludgeoned by all of us, conservatives and progressives alike, to build and feed a far-too-large civilization.

The charts above all start in 1820, when human population first reached one billion. 200 years and 7.2 billion additional people later, our planetary impacts are heading off the charts… as the chart below demonstrates. Note the red line for population and everything else tracking skyward with it.

I could offer up several more charts and graphs that tell a similar story about the last two centuries on Earth: mining and plastics production soaring, forests and fish populations in steep decline, atmospheric and oceanic chemistry changing, wetlands disappearing, and much more. Lots of amazing work in policy, philanthropy, and technology is being done to reduce or even reverse some of these trends, but we’ve already crossed several thresholds to arrive here, isolated in our boxed-in lives.

And that’s the second feature of the politics of loneliness I want to highlight: As we elect and re-elect leadership who fail to help change the cultural story, who fail to slow and stop the erasure of the more-than-human world, we’ve been making ourselves and our fellow species lonelier.

I’ve been tempted here to ask a rhetorical question: Is anyone lonelier than men like Trump and Musk? The woodcutter is now king of the forest, but each surviving tree is still happier than he is. Who is emptier than a successful narcissist?

But these are useless questions. For one thing, the consequences of Trump’s election are far more important than he is. And, in the reality that surrounds our stories, all the species threatened with extinction are certainly much lonelier than a grossly entitled human. Every community of plants and animals that connect with and rely upon each endangered species is lonelier too. And so, in the end, are we, even if that’s not what our stories are telling us.

To cite one example you probably haven’t heard of in a country you may not recognize, the Príncipe scops-owl is a critically endangered member of the ecological community in São Tomé and Príncipe, a small island nation off the west coast of central Africa. Locals have known about the owl forever, but scientists only recently identified it. Intolerant of human development, the tiny owls persist only in a small protected area of old forest. Their diminished population may disappear in a few decades, but that’s not really a surprise. 10% of Earth’s plant and animal species may not survive the century.

In an era suffering the delusion that humanity is close to spreading out to Mars and beyond, the decimation of this planet’s biodiversity is the far more important trajectory that every scientist and engineer connected to NASA should be seeking to correct.

We cannot doubt that our vision of us as alone in the universe is directly related to the accelerating extinction rate for our fellow species. As various saints and soldiers in the fight to conserve and recover biodiversity keep pointing out, we cannot save what we do not see or love.

And the longer the lunatic question - Are we alone? - defines our sense of self (a lonely intellect devouring its inanimate planet as it searches longingly for other intelligences in the galaxy), the more damage we will inflict on life. As the climate and biodiversity crises deepen, we see the consequences of our false self-image. And as extinctions accelerate, we risk the irony of becoming alone for the first and final time.

Here’s a rule I would like to insist upon: Nobody leaves this planet until we repair what we’ve destroyed and rewild what we’ve bulldozed. Or as a wit on Mastodon posted a while back, “Be the ancient advanced alien race you want to see in the universe.” Which makes sense to me. If we’re going to cos-play as aliens here at home, then let’s be the kind of aliens that would make the best possible humans.

3. Don’t Be One Species

What qualities might that best-case advanced alien race have? And why haven’t they shown up? As Elizabeth Kolbert explained so wonderfully in the New Yorker, it might be that the more they resemble us the less likely they are to exist, much less arrive:

Wherever we go, we’ll take ourselves with us. Either we’re capable of dealing with the challenges posed by our own intelligence or we’re not. Perhaps the reason we haven’t met any alien beings is that those which survive aren’t the type to go zipping around the galaxy. Maybe they’ve stayed quietly at home, tending their own gardens.

Like Gregory Bateson, Kolbert sees that the problem lies with the difference between the real world and how we think about it. The urge to focus on tools and technology as if they exist apart from Earth and ecology is a sign of failure. Why would a species that truly belongs to a planet, that embraces and respects its full living community, think much about going somewhere else? Good scientists know that the best science is rooted in a love of knowledge, but knowledge is not enough. That love must be secondary to a greater love.

Barry Lopez, in perhaps the least gentle pair of sentences he ever wrote, addressed the consequences of not aligning our thinking with how nature works:

Only an ignoramus can imagine now that pollinating insects, migratory birds, and pelagic fish can depart our company and that we will survive because we know how to make tools. Only the misled can insist that heaven awaits the righteous while they watch the fires on Earth consume the only heaven we have ever known.

So what do we do?

As I’ve noted before, the answer begins with what environmental philosopher Kathleen Dean Moore says when asked, “What can one person do?” She replies: “Don’t be one person.”

I might add, “Don’t be one species.” There is really no such thing as an individual, despite what our stories tell us. We think of ourselves as a mind encased in a skull carried by a body, but it’s probably wiser to admit we’re a) a complex container for microbial communities we don’t yet understand and b) a node in a multitude of natural communities that buzz and hunt and flutter in the wind.

And that’s a third feature of the politics of loneliness: The solution to much of what ails us is to act as if every aspect of our lives is a function of community. Which, of course, they are. Human community, certainly, but also the more-than-human community that fills, surrounds, nurtures, and amazes us.

I wrote above that we act as if there are no objective, permanent maps and guardrails, but of course there are. We are governed by physics and chemistry, to begin with, and then by the principles of ecology that explain interactions within the living world. And, here on our little island in space, we are subject to Earthly limits to our growth. The economies we prioritize above all else are only dangerous games played within ecologies.

But these are not our Anthropocene stories. We’re taught instead to turn lives into objects and ecosystems into commodity-filled warehouses. These stories are formulas that serve neither reality nor our own best interests. Increasingly, the calculations include each of our lives too, with our data harvested alongside our labor and our ideas.

I’ll close by noting a mistake I made at the beginning of this essay. Stories, I asserted, are an act of our strange human intelligence. We invent them constantly to remind ourselves how to live. This is all true, but the deeper reality I neglected was revealed to me in a powerful sentence by Robin Wall Kimmerer in The Serviceberry, which I’m now rereading. The sentence is tucked into the ending of a passage about how we’ve “surrendered our values to an economic system that actively harms what we love.” She reminded me that everything goes back to the source: all values, all relationships, and even all of our words.

There is no formula complex enough to hold the birthplace of stories.

All the stories our ancestors told came from the source. Many people today, whether Indigenous or simply rational, still tell stories rooted in reality. The error of our current era is that we think of ourselves as the source, and so only value ourselves. The task ahead, then, might be described as a quest to explain all of this to the woodcutters and the aliens they’re turning us into.

We can start by acknowledging that we are not alone.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

First, a long overdue recommendation of

and for any reader who wishes to be charmed, haunted, and astonished by writing steeped in both moments and centuries. I spent the day today listening to many of his exquisite essays, and could do it again tomorrow. Knowles sings his way into and through the land (northern UK, Ireland, outer Hebrides) with a hint of both Dylan Thomas and Tom Bombadil. There’s poetry in every sentence and depth to every thought.From Noema, a truly fascinating and deeply disturbing history of the bulldozer. Please note: You’ll need a strong stomach for this one. I have long thought of bulldozers as symbolic of human activity in the Anthropocene, but I had no idea how right I was. The name originates with the bullwhip, became a slang term for racist lynching thugs during Reconstruction in the South, and then was applied to the steel blades and machines we used to level much of the planet. Bulldozers are also a primary tool of warfare, used to erase buildings and bodies. The story of the bulldozer is the story of converting and colonizing the Earth.

For an equally fascinating but entirely wonderful alternative to the bulldozer story, listen to this Radiolab piece on the astonishing likelihood of migrating birds using quantum entanglement to see the Earth’s magnetic field as they fly at night. As a side note to this wild scientific tale, we learn that birds migrating through the center of North America have the capacity to hear the low roar of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans to their left and right.

From the Guardian, a good-news announcement from a follow-up meeting to last year’s COP16 biodiversity conference: A last-minute deal was struck to promise billions of dollars to protect species and habitats. The COP16 president wrote afterward that “We achieved the adoption of the first global plan to finance the conservation of life on Earth.”

Also from the Guardian, an article based on a new book about what kind of fossils our mountains of waste and planet-altering civilization will create millions of years from now.

From the Revelator, good work being done in the U.S. and UK on replanting vital seagrass meadows.

From Nautilus, an interview with the author of a new book on the fascinating science of aerobiology. As I’ve written, it’s only recently that we’ve come to think of the atmosphere as a habitat on par with the continents and oceans. The author introduces it this way:

The atmosphere is like an overhead ocean, filled with its own vast menagerie, known as the aerobiome. Swarms of insects, both giant and invisible from the ground, migrate for hundreds of miles. In a 2024 study, researchers determined that 9 trillion insects pass over a few hundred square miles of China every year. Spores of moss and fungi cross oceans. Bacteria and viruses rise from ocean waves and forest canopies. They can float up into the upper atmosphere. Even the clouds are alive.

It's a pity more people don't subscribe to you. Your writing, ideas and facts are essential now for survival.

I know: to the trees, but not to us,

Perfection of the life is given, whole.

And on the Earth – the sister of the stars –

We live in exile, while they are at home.

Nikolai Gumilev