Hello everyone:

There is far too much to say about the brutality and ugliness of the budget bill moving through Congress. Whatever happens, life for both humans and the more-than-human world will suffer at the hands of a few failed but powerful souls working against all that is good, fair, and rational. I’ll be sure to write about the environmental/ecological consequences at some point, but not this week.

Heather and I are away for a good part of July. I’ve set this and two other essays to post on the Thursdays while we’re gone. Each was originally published in the Field Guide’s early days, as far back in 2021, when the work was new and readers were few. I have, however, spent quite a bit of time thoroughly rewriting and updating the essays.

Enjoy.

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read some curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

Heather and I have been fortunate enough, on a few occasions over a few years, to spend a week in a sweet, simple, century-old cabin owned by some very generous friends. It’s a few feet from the water on a small rocky point of a quiet Maine island. We were only a mile from the mainland, and only two miles as the herring gull flies from our house, but the quietude is a million miles from the mediated catastrophes and politics of the built world. No breaking news, no updates. No pavement, no cars, no traffic or roadkill. No to-do lists of things we don’t want to do.

It’s good-old-fashioned, mid-20th-century rustic living, with propane-fueled lights, stove, and fridge, and a bucket of cedar shavings in the outhouse. We have our phones, sure, but they’re used almost entirely to photograph flowers and bugs and fungi we identify once hunkered down on the porch for the evening with our guide books and a gin and tonic.

The Anthropocene is visible everywhere, of course, from the plastic Gatorade bottles, pressure-treated wood, and Styrofoam buoys washing up in the coves to the diesel-powered lobster boats churning slowly around the bay as they farm lobster with thousands of plastic-coated wire traps baited with fish hauled in from elsewhere.

We spend our days slowly observing the beautiful surface of the altered world. Often this is the sheen of the bay occasionally ruffled by breeze or buoy or boat, or broken by desperate schools of mackerel pushed upward by seal and cormorant. Sometimes, on walks along the island’s narrow dirt roads, it was the caterpillar-haunted underside of milkweed leaves, the 1/8th inch flowers of Dwarf Enchanter’s Nightshade, or the wonderfully weird Hydnellum peckii dotted with beads of what looked like strawberry jelly.

A Variety of Darknesses

The only place I looked beneath the surface was at the harbor’s edge at half-tide. I sat quietly and watched small fish dart out cautiously from stony crevices and the dark haunts of rockweed. It was like an aerial glimpse into a fascinating fragment of an endless city. As I’ve written here before, we know so little of the sea, though it surrounds us always and feeds us daily.

More broadly, we think of ourselves as an all-seeing species, but really we live in a variety of darknesses. Animals and plants all around us have abilities we only dream of. We’re as blind to most of the electromagnetic spectrum, for example, as we are oblivious to the microbiome that determines much of our body and mind. We don’t know what we don’t know, and we can’t see what we can’t see. Science informs us about both, but science is only a part-time advisor to culture.

We surround ourselves with windows, and think that everything else is transparent to us too.

Other than water, the list of Earthly things we can actually see through is quite short. Translucency is common, but transparency is rare. We evolved alongside water and ice, jellyfish, amber, diamonds, Muscovite mica, and some other clear crystals, but that’s about it. (Well, there’s also the clear aquarium of the eye itself, through which a fragment of the world reveals itself.) Today we can add glass and certain ceramics, and the plenitude of clear plastics, but the list remains short. The world is generally opaque, and that’s especially true of all that lies below us.

We live on the skin of a globe whose interior we rarely see or think about.

As Robert Macfarlane puts it in his opening pages of his astonishing 2019 book, Underland: A Deep Time Journey,

“We know so little of the worlds beneath our feet. Look up on a cloudless night and you might see the light from a star thousands of trillions of miles away, or pick out the craters left by asteroid strikes on the moon’s face. Look down and your sight stops at topsoil, tarmac, toe. I have rarely felt as far from the human realm as when only ten yards below it…”

I had a chance to read Underland while on the island. And to think about it, at length. I’ll say first that Underland is not a book about the Anthropocene so much as it is a book that masterfully inhabits and articulates the Anthropocene while exploring our history with the worlds beneath our feet. Those worlds, whether caves or mines or the interiors of soil and glacier, have a lot to say about our ignorance, cruelties, biases, and catastrophic mistakes, even as Macfarlane – always gentle and honest – simultaneously weaves in narratives of our countervailing virtues of intelligence and creativity and courage and activism and optimism.

The book is in three sections: Seeing, Hiding, and Haunting. All of it takes place in Europe (if you count the UK and Greenland as part of Europe). The chapters in Seeing take us caving in a limestone region of England (“Burial”), driving at high speed through a 600-mile mine network that stretches out beneath the North Sea (“Dark Matter”), and exploring the fungal networks that we now know redefine forests as interconnected communities rather than a collection of competitive species (“The Understorey”).

Hiding takes us into the catacombs under Paris (“Invisible Cities”), a subterranean river in Italy (Starless Rivers), and a brutal buried history in Slovenia (“Hollow Land”). And in Haunting, Macfarlane journeys to Norway for a difficult pilgrimage to a remote cave art site (“Red Dancers”) and a conversation with a fisherman about the battle against oil companies who want to drill through his rich fishing grounds (“The Edge”); to a rapidly changing Greenland for two glacial journeys (“The Blue of Time,” and “Meltwater”); and to Finland to tour a deep, eerie storage facility for nuclear waste (“The Hiding Place”).

Metabolizing Landscape into Lyrics

In its structure, Underland is a typical work of narrative nonfiction, a captivating blend of environmental journalism and cheerful travelogue. He has stitched together several journeys, each interesting and well-told. But Macfarlane’s writing, research, and meditations on what it means to be human set his work apart. Perhaps above all it’s his lyricism that sings us into awareness. As one reviewer phrased it, he “seems to metabolize landscape into lyrics as he walks.”

Opening Underland at random, I’m with him driving through Slovenia in his “Hollow Land” chapter, and find this:

The true peaks of the Julian Alps are now beginning to show on the horizon: a Gothic dream-range. Limestone summits spiral up to towered tops. Structures of hollow and fold replicate up and down the scales, from ridges and valleys to the water-scores on a single boulder. Matter shifts appearance, changes place. It is hard to tell cloud from snowfield from pale rock-face.

Macfarlane is a poet of the present tense in these journeys, but the poetry is woven inseparably into his brilliant feeling and thinking about where he is and what it means. In Slovenia, the conundrum at hand is the brutal use of the beautiful karst (cave-riddled limestone) landscape as mass murder and burial sites during WWII and later.

He casts a wide net in which many disparate stories are gathered to glitter. In the paragraph after the one quoted above, Macfarlane weaves together two tales. The first is from the narrator of a W.G. Sebald novel, horrified by the continuum of cruelty to a coastal British landscape, and the second describes the unexpected uncontrollable weeping of a friend he traveled with to the same landscape – a former nuclear weapons test site – which “caused the surfacing in her, unbidden, of memories of a cruel relationship in which she suffered for many years.” He ends the paragraph with a borrowed line, in italics: The violent event persists like crushed glass in one’s eyes. The light it generates, rather than helping us to see, is blinding. Only in the Notes do I learn that it’s from an obscure 1996 academic book on the anthropology of violence.

Macfarlane is a deep and thoughtful scholar, and the information load his prose carries, in the mode of Barry Lopez, is often substantial, but it never weighs down the narrative or its emotive power. His prose is elegant enough to let the woven paragraph work its quiet magic.

Here’s a little more magic from the next paragraph, which describes a Slovenian roadside scene: an elderly woman in a wheelchair among the boulders of a river’s edge, alone, watching the “whirling blue water.” She is a fragile anomaly in a hard place, put there by unseen hands. Macfarlane drives on, and writes on, slipping now into a long paragraph typical of his writing, at once intellectual, historical, philosophical, and personal. It’s worth quoting at length:

Dissonance is produced by any landscape that enchants in the present but has been a site of violence in the past. But to read such a place only for its dark histories is to disallow its possibilities for future life, to deny reparation or hope – and this is another kind of oppression. If there is a way of seeing such landscapes, it might be thought of as ‘occulting’: the nautical term for a light that flashes on and off, and in which the periods of illumination are longer than the periods of darkness. The Slovenian karst is an ‘occulting’ landscape in this sense, defined by the complex interplay of light and dark, of past pain and present beauty. I have walked through numerous occulting landscapes over the years: from the cleared valleys of northern Scotland, where the scattered stones of abandoned houses are oversung by skylarks; to the Guadarrama mountains north of Madrid, where a savage partisan war was fought among ancient pines, under the gaze of vultures; and to the disputed valleys of the Palestinian West Bank, where dog foxes slip through barbed wire. All of these landscapes offer the reassurance of nature’s return; all incite the discord of profound suffering coexisting with generous life.

Remember, all of this was on one page I randomly turned to in Underland for the purpose of this essay. That’s an indication of how rich, beautiful, and rewarding this book is.

Speaking in Spores

The substance of these journeys is told through artful and wise conversation, most notably perhaps with Bjornar Nicolaisen, a Norwegian fisherman, and Merlin Sheldrake, a plant scientist. Nicolaisen is cycling through rage, activism, and psychological exhaustion as he struggles to rally Norway to value its fishing traditions over the short-term quest for petro-wealth. Sheldrake tours Macfarlane through the still scarcely understood underland of fungi-facilitated interconnections beneath the forest floor, nicknamed the “wood-wide web.” Both serve as guides to the underworld, whether below the waves or beneath our feet.

But as cute as the wood-wide-web metaphor is, it highlights a problem that Macfarlane and Sheldrake discuss: We don’t have the language to properly describe the more-than-human world we’re changing and erasing. Sheldrake explains, with some bemusement and philosophy, that the mycorrhizal network fungi create to link root to root is often described in research papers in weirdly economic or political terms, either as an exchange of goods or as a social utopia:

Why should we expect fungi and plants to behave as humans started to behave economically in the eighteenth century, with the emergence of the limited liability corporation? I find it so bizarre… But I’m also sceptical of the socialist dream of fungi as sharing and caring, a rose-tinted vision that sees trees as nurses… I’m tired of both of these stories… The forest is always more complicated than we can ever dream of. Trees make meaning as well as oxygen. To me, walking through a wood is like taking a tiny part in a mystery play run across multiple timescales.

Macfarlane responds:

“Maybe, then, what we need to understand the forest’s underland,” I say, “is a new language altogether – one that doesn’t automatically convert it to our own use values… Perhaps we need an entirely new language system to talk about fungi… We need to speak in spores.”

“Yes,” says Merlin with an urgency that surprises me, smacking his fist into the palm of his hand. “That’s exactly what we need to be doing – and that’s your job,” he says. “That’s the job of writers and artists and poets and all the rest of you.”

Speaking in spores, as Macfarlane playfully suggests, is entirely foreign to us. We don’t have a grammar which automatically gives life or intention to the natural world, as many indigenous languages do. In English, especially, trees and islands and fungi are dead objects that our language distances from us, and from each other.

A Deep Time Journey

Again and again, Macfarlane explores the underlands to help us understand their place (or absence) in our consciousness and our conscience, from Neolithic burial sites to the dead crossing the Styx to the impending collapse of the Greenland ice sheet to the conundrum of storing nuclear waste safely for the next 10,000 years.

A thread that binds much of these disparate stories together is in his subtitle: A Deep Time Journey. Before the Anthropocene, much of our activity in the underlands, real or imagined, was in reverence of deep time. We buried our dead to launch them on eternal journeys and we made cave art as secret and sacred representations of our small place in the unending universe.

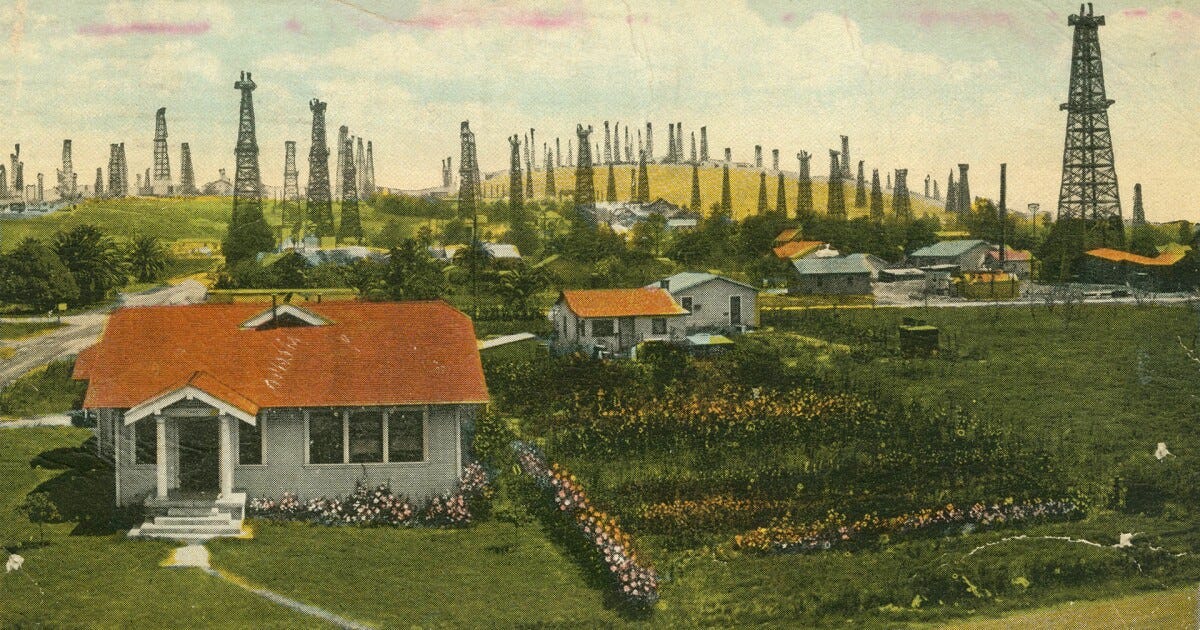

Now, we hollow out regions of the deep Earth to feed our surface (and often superficial) needs. We’ve drilled 30 million miles of holes in our various petro-quests, and mined - in a matter of decades - millions of years of accumulated coal, oil, gas, potash, salt, and various minerals. And in burning much of what we’ve unearthed over the last century, we’ve permanently destabilized much of the planet’s ice. Un-Earthed, indeed.

In related news, it rained on the summit of the Greenland ice cap in August of 2021. No one had ever seen that before.

Our relationship with deep time is as profound as ever, but where we once documented our awe we now erase the past.

I spent my evenings on our quiet island reading and thinking about Underland. (I’ve barely scratched the surface here.) There was plenty of Macfarlane’s dissonance to go around, not least as I sat on the screened-in porch reading late into the night with a headlamp, a spelunker or miner working his way down into the caves of metaphor.

Also, the lovely cabin we inhabited was once a bunkhouse for men who worked in the island’s 19th century fish oil processing plant for a few years before the fish population crashed. The island, once a thriving fishing and farming community, had its pre-contact mature forests razed for timber or firewood and its soil compacted by livestock. A forest is back, but it’s not the same forest. The deep history of the coast and islands, those long millennia in which a small, rationally-sized population of the Wabanaki lived in the landscape, was scarcely visible. But it’s there, in the understory under our story.

I should close by saying that our time on the island is always wonderful, slow, and beautiful. My “occulted” view of those times, however informed it may be by Underland’s reminder a) that the natural world lives as islands in a human sea, and b) that from any point on Earth we can see and acknowledge and grieve the Anthropocene, was certainly more full of light than dark.

Life continues with us, for us, and despite us.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

From National Geographic, an interview with Edward Burtynsky, the extraordinary photographer of the human-altered world. The interview is richly illustrated with his images, so click the link for those alone. I dearly wish I could publish his photos here in the Field Guide; they say in one image so much of what I try to accomplish with a few thousand words every week. Burtynsky has spent decades capturing the scale of our impacts on Earth in images both tragic and beautiful, and articulating alongside those images a clear and concise account of how alien our actions are. The entire interview is worth reading, but perhaps the most interesting thing he says is this:

If we think of the sublime, in the traditional sense of the word, it’s nature that is the omnipresent force, whether it’s gale-force winds, or a hurricane, or volcano or a ship lost at sea. And we are diminished and in awe of this force. What I started to realize was that we ourselves are becoming sublime. That we are dwarfed by our own creations. We are working at a scale that is changing the planet: We’re diminishing life in the oceans, mountain glaciers are melting, forests are disappearing, and all of that is happening at a rapid pace. It’s like we’ve entered the technological sublime. We’re now small players in the theater of our own making.

And just for emphasis, from the International Center for Photography in New York, an announcement of a huge showing of Burtynsky’s work through late September. I’m very much hoping to get down there to see it. I recommend it to anyone. You’ll see why when you view some of his images in both this press release and the Nat Geo article.

From

and Story Ecology, “A brief history of rain,” a wonderful, multifaceted, wise, and personal introduction to the wild beauty of a phenomenon we are far too often inured to in our boxed-in lives. It’s an excellent companion piece to one of my more popular essays here, “Reimagining Rain.”From Canary Media, a profile of a long-time New England fisherman who has crossed the divide between the fishing community and offshore wind power developers, profitably working on both sides but facing an uncertain future in the anti-renewables Trump era.

From

via of The Elysian, a thoughtful and comprehensive essay on “rewilding the Earth at scale,” by someone doing the work on both a global and local level. He is as honest about the sorry state of the altered planet as he is enthusiastic about the power of folks to make a real difference right where they live, by rebuilding healthy relationships with the land and with each other:We live in an ever-hollowing husk that threatens to crumble if we don’t reverse course. Beyond nostalgia, my activism seems so uncomplicated, so simple. I don’t want to live in the crumbling. I don’t want to live in the frayed end of a rope we hang ourselves by. I want to see the recuperation of the world. I want to see the planet refill with the million species that humans have put at risk of extinction. The fullness of the world—the beaver, otter, salmon of it all—are the hallmarks of a healthy, robust ecosystem that I can rely on into my future and the future of the generations beyond me.

I see a world that has lost much of its resilience. The web of life that sustains us is thinning and breaking. I want that resilience rebuilt, reconnected node by node.

And from

herself, “Maybe an Exowomb is Better than Pregnancy,” a review of the 2023 sci-fi/romantic comedy, The Pod Generation, which contemplates the ethics and ecological consequences of a near future in which some parents have the option of gestating their child in a portable artificial womb.From

, “How to Feed 9 Billion People Without Trashing and Overheating Earth,” a podcast conversation with and on the topic of Grunwald’s new book, We Are Eating the Earth.

Beautiful essay and review. Definitely on my TBR list now. Thank you!

Heartfelt and Beautiful post.