What Endures

12/18/25 - Lichens, the solstice, and community

Happy Solstice, everyone:

This will be my last post of 2025. Christmas and New Year’s Day both fall on a Thursday, my publication day, and while it’s tempting to offer you some light fare and good news on those days, I think it makes more sense in this busy time to slow down, go offline, and leave you instead with my well wishes for the solstice, the holidays, and the dawn of 2026. I’ll be back in your inbox on January 8th. For those of you outside these traditions, I hope you’ll welcome the short break as well.

After more than four and a half years, this is my 243rd weekly Field Guide post. Nearly all have been original essays rooted in some combination of in-depth research and a writer’s intuition honed over decades of writing in the ecotone between poetry, science, and landscape. I’ve loved the challenge, and feel incredibly fortunate to be a working writer paid to explore what has haunted me for much of my life: How we arrived at, and what we do about, this critical moment in both human and Earth history.

I’m still devoted to not paywalling the Field Guide, but in hopes of making the work financially viable, I’m making one small change to try to convert a few more readers to paid subscriptions. Starting in the new year, only the most recent six months of the archives will be available to free subscribers. And someday, if I commit to writing a book based on my essay “We Are Not Alone,” paid subscribers will have access to drafts and notes on that project.

One more thing: I’m offering an incentive for becoming a paid subscriber between now and New Year’s Eve. (If anyone would like to pay but needs a more discounted price, just let me know by replying to any of these weekly emails.)

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read some curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

Parasites and Endurance

With democratic values and basic decency under threat these days, it’s easy enough to believe that parasites endure while the rest of us suffer. And even as we turn to the more-than-human world for respite, there is an astonishing and little-known truth that might, at first glance, unnerve you: A majority of animal species are parasitic. This is largely accounted for by the little things that run the world - like the million or so species of parasitic wasps - rather than the cheerful charismatic megafauna we think of as animals, like giraffes and fishers.

If that parasite-to-host ratio seems like an imbalance that reflects on Anthropocene tech culture, private equity greed, and grifter politicians, take heart: The balancing that occurs across life is not between animals alone, but throughout the entire tapestry of life. Plants and microbes make up most of the Earth’s abundance, and the Sun’s energy cycles through them and us and everything else in the good green play of existence. As I’ve written, parasites are as natural and necessary to that flow of energy as pansies and pandas. And as the cheerful parasitologist in the New Scientist article linked above says, “The more intact the ecosystem, the more parasites you tend to find there.”

We need to be careful about our environmental metaphors, it seems. We are daily reminded, after all, that political and power-seeking humans are neither culturally nor ecologically normal.

Relationship is the Fundamental Truth

So what does endure? What anchors our reality? There are a lot of good answers. The upcoming solstice is a fine example, reminding us that the music of the spheres plays on, heedless of the Earth’s biological machinations. But I’ll get back to that. My first answer is from this biological realm. What endures here, from within cells to across landscapes, is community.

We are not alone, as I keep reminding myself (and you). All of life is community. Or, rather, communities of communities. I don’t mean that life is all one big genetic family, though it is, nor that “community” is a synonym for peace and tranquility. I mean that there’s no such thing as an individual, and that every living organism is plural on the inside and networked endlessly on the outside.

Look within, and find that mitochondria, like Mike Mulligan’s steam shovel, were ancient free bacteria before becoming the powerhouse of most living cells on Earth, including those of your body (and of the trillions of microbes in your body). Chloroplasts, too, the miracles behind the miracle of photosynthesis, are former bacteria now embodied in nearly all plant cells.

Look without, and see these concentric spheres of life incorporating life everywhere. Around me here in coastal Maine, I see that each chickadee and red oak contains multitudes, and are each contained by a multitude of relationships. Oaks play host to hundreds of insect species, for example, and the chickadees in their feasting on thousands of these insects are linked in a trophic cascade to every other species of plant and animal linked to those insects. And so on.

“Relationship,” said Rabindranath Tagore, “is the fundamental truth of this world of appearance.”

Lichens on a Grand Scale

But the communities within communities that have been on my mind this week are the symbiotic organisms we call lichens. Walking through the December woods, I cannot escape their beauty glowing from tree trunks between slant-lit winter sky and freshly-fallen snow. Lichens are everywhere, in extraordinary complexity, reminding us that the trunks we imagine as simple brown stems are awash in the textures and colors of these incredible life-forms.

Lichens are composed primarily of a fungus and one or two types of photosynthesizing algae. Millions of algae cells eat light to produce sugars for the fungus, while the mesh-like fungus provides structure, protection from the elements and predation, and other beneficial chemistry that lichenologists are still unraveling. Beyond that basic set of relationships, though, it seems that lichens also have embedded within them yeasts and non-photosynthesizing bacteria whose functions are not yet known. Given all this, it might be better to think of lichens not as species at all but instead as small, simple, flexible ecosystems.

Colors vary from bright yellow and orange to dull brown and black, the color defined by the type of algae and the level of exposure to sunlight (brighter colors are a more effective sunblock). And genetic variation in lichens seems to be endless. About 20,000 species have been identified, but because lichen fungi may associate with different photobionts (the light-eating algae) according to different ecological needs, and because at least a quarter of the 1.5 million fungus species are capable of becoming lichens, there may be as many as 250,000 lichen species.

If you need to go outside right now and find a symbol of what endures, look up at the Sun and then look around for a lichen. They are ubiquitous, living from Pole to Pole, and some can survive in space. Some larger lichens in Antarctica are several thousand years old, growing slowly but relentlessly in that biological desert of ice and rock. When I was a young word nerd finding my footing in the Antarctic, I was pleased to be introduced to the concept of endolithic lichen, extremophile organisms surviving at the end of the Earth by holing up inside tiny pores or crevices in stones (endo = within, lithic = of stone).

One of the few things I remember from a botany class in college was that lichens may be an example of “controlled parasitism” rather than mutualism (when both benefit equally), with the fungi getting more out of the deal than the algae. But forty years later, that’s still an ongoing debate, as the mysteries of lichens only deepen. Still, it’s a reminder that relationships in nature are at least as complicated as in human society.

I had planned on writing an entire essay on lichens, but after doing some research I found that my ideas could not escape the orbit of all the beautiful writing that Maria Popova in The Marginalian has done to celebrate them and to find the lessons they have to teach us. I highly recommend you read them. For now, I’ll let this paragraph host the links for her wonderful thoughts about lichens, which she tells us are

living reminders that the supreme vital force of life is not competition but interdependence, that we survive and thrive not through combat but through collaboration.

Popova quotes the wonderful naturalist and writer David George Haskell, who uses lichens to get at the larger truth of the vast microbial galaxy that inhabits our bodies:

We are Russian dolls, our lives made possible by other lives within us. But whereas dolls can be taken apart, our cellular and genetic helpers cannot be separated from us, nor we from them. We are lichens on a grand scale.

After Us, What?

I should admit that all my talk about community is coming from a semi-reclusive writer who doesn’t do nearly enough in my community. The importance of community, like joy, is a lesson I have to relearn every time I emerge from my writing. And though I’m aware that even our sense of consciousness may rely to an uncomfortable extent on our microbiome, I’m still stuck in the notion of “I”, even as me and my microbes write our way through these essays about the beautiful interlinked world and our species’ self-serving transformation of it.

Everything here on my desk, in this house, on this peninsula and continent and planet is rooted in the community of life and the energy exchanged through it in a dance that has gone on for a duration so long it would burst our Christmas-shopping minds to comprehend it.

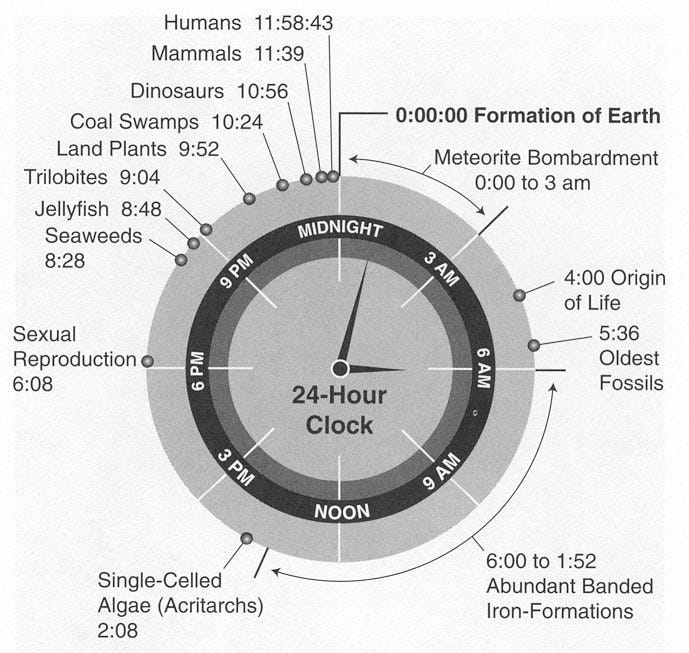

The graphic above shows what the history of life on Earth looks like when converted to a 24-hour day. Life originated around 4 a.m. (always a mysterious hour), plants colonized the continents just before 10 p.m., and humans arrived a little over a minute ago.

Considering how much of the last few billion years here have been characterized by a thin smear of single-celled life on an inhospitable stone in space, what makes this time you and I share on the ancient Earth so astonishing is that we’ve been born into an age defined by extraordinary floral and faunal complexity and beauty. This is also what makes the Anthropocene so criminal. We’re born, on one hand, into the unlikely Edenic grace of biological lushness, but on the other into a culture that eats away at it like acid.

The question is, then, what will endure after the Anthropocene? The fate of the Earth, strangely enough, will be defined by our behavior as a community within the greater community.

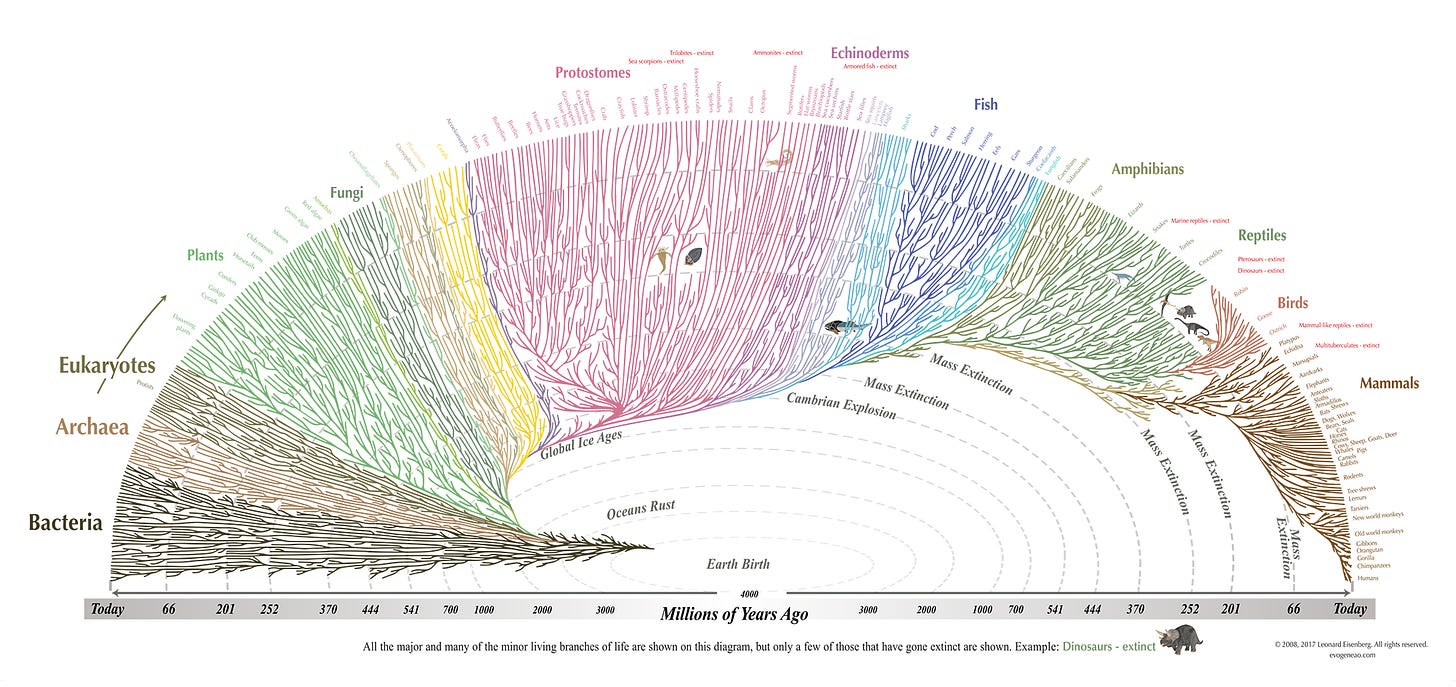

A Tiny Wind-Driven Human-Shaped Wave in a Wine-Dark Sea

I noted earlier that all of life, genetically speaking, is one big, extended, strange and marvelous family. Here’s a chart that illustrates that. It’s the Evolutionary Genealogy family tree, and it maps the history of life through time, like a four-billion-year-old family tree. The origin of the Earth is bottom center and our current moment is the ring’s outer edge. All the stems that end somewhere in the middle are life that no longer exists. As in any family tree, dead ancestors dominate. Most forms of life that have graced the Earth are extinct, and we are their descendants.

Looking left to right, you’ll see that life began with bacteria, which persisted but also branched endlessly outward into multicellular organisms of increasing complexity, from lichens to lice, lionfish, and leopards.

For a mix of quirk and awe, check out the interactive version of this chart, in which you can click on species to find out their genealogical relation to you or each other. For instance, click on “fungi” to discover that a King Bolete mushroom is our “697 millionth cousin, 303 million times removed.”

All of this is to say that life endures. And its complexity and beauty endure too. The Anthropocene will not end life, only diminish it without good cause.

And yet, noting that the foundation of all life today is a few billion years of the extinctions that naturally accompany evolution, the chart is a reminder that of all things that endure there is a center point: the absence of life we call death. I wonder, though, if perhaps it’s better to think of death not as an absence at all but the return to what we’ve always been: possibility. Alive or dead, surgeon or soil, we’re always potential energy existing in complex relation with the community.

All matter is borrowed light, and all light - if I have any understanding of the universe - is borrowed time. Life is an astonishing flower rooted in a rare plot of galactic soil, which is itself a product of the vast energy and mass of the universe we have yet to identify (much less understand), all of which is a flowering of something stranger yet. Within all that, we and our busy consciousness blossom briefly before reverting back to that greater mystery we emerged from, a tiny wind-driven human-shaped wave in a wine-dark sea.

I’m reminded of my mentor Charlie Simic’s poem, “Stone,” which invites us with good humor into that greater mystery. Fable or riddle, the poem is endolithic desire, a wish to find eternity in the simplicity of a stone:

Stone

Go inside a stone

That would be my way.

Let somebody else become a dove

Or gnash with a tiger’s tooth.

I am happy to be a stone.

From the outside the stone is a riddle:

No one knows how to answer it.

Yet within, it must be cool and quiet

Even though a cow steps on it full weight,

Even though a child throws it in a river;

The stone sinks, slow, unperturbed

To the river bottom

Where the fishes come to knock on it

And listen.

I have seen sparks fly out

When two stones are rubbed,

So perhaps it is not dark inside after all;

Perhaps there is a moon shining

From somewhere, as though behind a hill—

Just enough light to make out

The strange writings, the star-charts

On the inner walls.

The Song of Matter and Light

Finally, then, and speaking of star-charts, I hope you’ll have a moment at 15:03 UTC on December 21st to mark the solstice. Though perhaps it’s best, here in the northern hemisphere, to wait for nightfall to stand between the Earth’s warmth and the cold shimmering stars while remembering that all these biological machinations occur among the unruffled, perpetual movement of planets and stars. It might be a good moment to wonder this: What does all this precious ecological communities-within-communities stuff, the work of abundance and parasites, the complex kinship of chickadees and oaks, the enlightened symbioses of lichens, and the endurance of mere millennia, mean to the cold sweep of galactic physics?

I suppose it means the same thing out there as it does in here: possibility.

The song of matter and light, like the dance of life and death, is about form and formlessness. It’s about transformation and time, about flowing in and flowing out, about making gifts of the gifts we’re given. I don’t think much about space, but I do like the image of the Earth as a blue-green beacon in the darkness, like a bit of algae turning light into sugar, inviting the larger forces at work in the universe to embrace it, feed on it, and spread out together slowly and relentlessly.

That’s all for now. I’ll be back after the holidays. Whether you’re celebrating or surviving the holidays and the turn of time’s tide, I wish you well. May your days, as the song says, be merry and bright. Thanks as always for being here.

And thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

From the BBC, several good-news environmental trends from 2025.

And from Sam Matey-Coste and the Weekly Anthropocene, another of his excellent round-ups of good-news stories in the transformation of energy systems and support for biodiversity.

From Reasons to Be Cheerful, good work being done to rewild the endless miles of utility corridors - land beneath power lines and over pipelines - into meadow habitat for insects and more.

Also from Reasons to Be Cheerful, women’s collectives in the Sundarbans in coastal India are restoring mangrove forests to build resilience in a stormier world and to help reshape the local economy around benefiting rather than diminishing nature.

From Mike Shanahan and Planet Ficus, another great post about the importance and wonders of fig trees, this one delving into the remarkable reproductive symbioses between figs and wasps, and whether you’re eating a dead wasp when you eat a fig.

From David Roberts and Volts, a podcast conversation with Senator Ruben Gallego about his new progressive energy plan and the future of Democratic politics around energy and the environment.

Hi Jason - thank you for the attention to lichens - they get far less attention than they deserve. Very well done. I was also unaware of Maria Popova’s writing, which looks very interesting.

You comment that perhaps it’s not correct to think of a particular type of lichen as a “species”. I have wrestled with the same notion myself. But I encourage you to ponder this: Are YOU a member of a single species: Homo sapiens? Given that about 50% of the cells in your body are NOT human, and are composed of (likely) thousands of distinct species of bacteria, archaea, and fungi, you (and every other human) are, just like lichens, really a “community”. An ecosystem masquerading as a single entity. The same is true of all other animals as well as plants. I’m pretty sure that there is a lesson here which humans would do well to understand about “working together”…🙂

Life = Communities.

We’re all plural, and connected.

World = Relationships.

...

Kin, linked, like lichens.

Complex, composed, composting.

Symbiotic, all?

...

What persists, endures?

In one, many or no form,

Possible light, Life.