Hello everyone:

I’m bringing back an (updated and improved) essay on a favorite topic of mine, the mystery of eel migration. There is so much to be said about the beautiful world, especially amid all the chaos of the Anthropocene. Eels offer a wonderful glimpse into the beauty and mystery.

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read some curated Anthropocene news. (The video by former astronaut Ron Garan about his awakening to the ecological reality of Earth is highly recommended.)

Now on to this week’s writing:

I’d been thinking about writing this week about the meteorite I found in Antarctica, and what it was like to hold a 4.55 billion-year-old orphan of the solar system, but I have once again become distracted by eels.

Why are eels a Field Guide story? Because, as the great Wendell Berry said, “To cherish what remains of the Earth and to foster its renewal is our only legitimate hope of survival.” So, I like to tell a natural history story once in a while to remind myself, and you, of what remains and what’s worth fighting for.

We in the north are in migration season again. The air has cooled, but the occasional monarch butterfly still passes through our garden here in coastal Maine. A pair of yellow-shafted flickers probed the yard a few days ago for grubs and ants to fuel their flight south. Warblers and their southbound companions have begun to mass and move down the coast together. You can watch this movement, at scale and in fine detail, via the remarkable Birdcast, which forecasts these migrations. Last night, for example, 264 million birds were predicted to be on the move across the contiguous U.S.

And so it goes, the vast seasonal movement of life all around us, some of it seen and much of it unseen, particularly from within our boxed-in lives. As I type this, birds are sailing overhead in the dark on their ancient paths.

Reading about migration is heartening in a way that is also overwhelming. Life swarms across every dimension of this planet in a profusion that should make us blush, not merely for the complex beauty of its movement but also because these migrations, unlike our own noxious traffic, enrich the world rather than deplete it.

There are the epic migrations of Arctic terns (a 4-oz seabird traveling 55,000 miles per year) and sooty shearwaters (only slightly less), bobolinks (songbirds shifting 12,500 miles a year between South American and North American grasslands) and bar-headed geese (traveling over the Himalaya at oxygen-deprived altitudes up to 23,000 feet), hummingbirds and humpback whales, caribou and tuna, wildebeests and walruses, swallows and salmon, and so many more.

There are very particular migrations like the great majority of eared grebes who converge from around North America to feed only in Utah’s Great Salt Lake and California’s Mono Lake each year. And there are the incredible, if less directional, peregrinations of albatross and swifts, feeding and sleeping aloft for months at a time, as if flying were not an effort but a state of being.

Migrations are made possible by physical and sensory adaptions beyond human capacity, whether navigating by smell, starlight, solar and lunar positioning, infrared light, or sensitivity to Earth’s magnetic fields.

All of these migrations speak of a planet knitted together by evolution over millions of lush, blue-green years, in which species experimented with long-distance survival strategies until extraordinary solutions emerged. How else would we end up living alongside the Arctic terns who live 30-year lives in which they travel the equivalent of three round trips to the Moon as they shift between polar regions? And how lucky are we that we live alongside the hard-to-imagine multigenerational migrations of monarch butterflies and green darner dragonflies who complete a migratory cycle around North America.

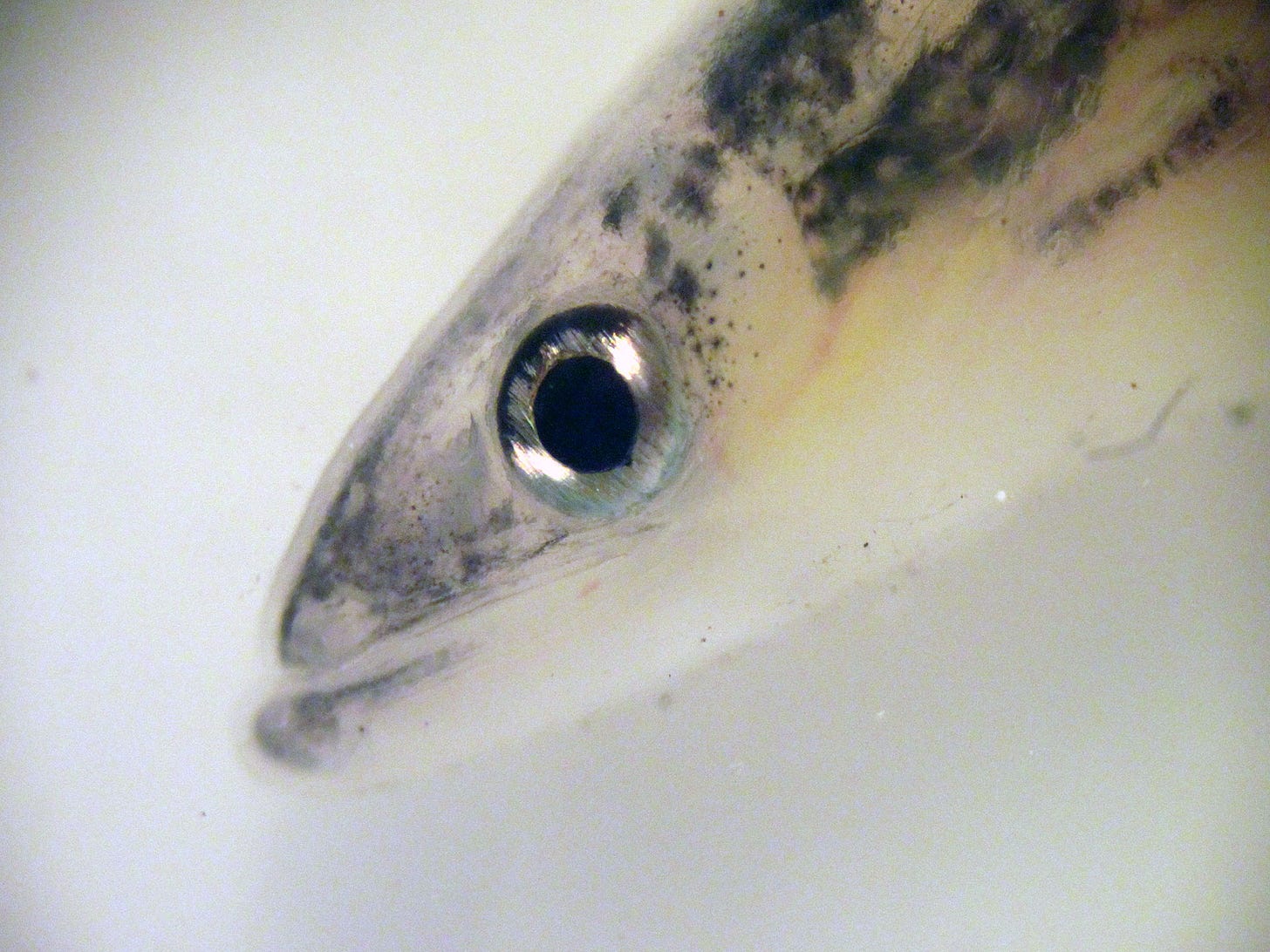

And then there’s the eel. Of the roughly 800 fish species we call eels, I’m writing here about the 15 species of Anguillidae eels, and mostly about American and European eels, but they are all fascinating. Freshwater eels migrate in and out of the waters of 150 countries. They are sacred to the Māori of Aotearoa/New Zealand, who “have over 100 names for eels describing their different colours and sizes, and they are revered as a link to the gods.” Other eel species inhabit inland freshwaters of Australia, Indonesia, East Asia, and islands of the South Pacific; here is a remarkable story of a researcher living among eels in the highlands of Tahiti.

Wherever they exist eels are beautiful, powerful, and strange. They add their own depth of wonder to the wonder of migrations. Here is just a sample of what makes American and European eels so fascinating:

They spend 7 to 25 years (or more) in their freshwater homes before heading back to sea. The reasons for such variation in migration timing is unknown.

Migratory eels can breathe through their skin, allowing them to leave the water and travel overland in moist areas.

They can swim backward as well as forward.

Eel gender seems determined by their ultimate location, with the majority of eels who migrate to the upper reaches of a watershed becoming female and most of those who remain downstream in estuaries or brackish water becoming males.

But eels don’t develop sexual organs until they prepare to return to their spawning grounds.

Eel gender was the focus of centuries of frustrated research in Europe, where no one (including Sigmund Freud, who dissected hundreds of them before retreating into psychology) could find the reproductive organs.

Females are two to three times larger than their future mates.

Unlike salmon, river herring, sturgeon, and other fish whose anadromous life cycle takes them out to sea to mature and then back to freshwater to spawn, eels are catadromous. They spawn in the ocean but live the bulk of their lives in estuaries, streams, rivers, ponds, and lakes. If you have marveled at the ability of salmon to find their way home to the same small stream where they first hatched, eels should boggle your mind. Theirs is one of the largest unseen migrations on Earth, and perhaps the most mysterious.

All migratory eels are born into mystery, and they return to that mystery to die. Well, we all are, but here I mean specifically that each eel species, whether in Tahiti or Hokkaido or Maine, has a particular spawning area in the deep ocean that has largely remained beyond scientific inquiry. For the Japanese eel (which exists throughout East Asia), it’s the West Mariana Ridge in the western Pacific Ocean. For the New Zealand longfin eel, it’s deep waters somewhere off Tonga. For South African eels, it’s an area north of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean.

Wherever eels spawn, we’ve never witnessed it. Only the Japanese, who consume 70% of the global eel catch, have gotten close. Through patient, methodical, and expensive ship-borne research they’ve tracked tagged eels swimming to an area of seamounts on the West Mariana Ridge and pulled up fertilized eggs in their trawls. More intriguingly, they’ve discovered that the eels spawn only at a depth of 150 to 200 meters and only for the last few days before a new moon.

This is a tale worth telling: Though they are often loners during their freshwater adulthood, eels end their lives in mysterious trysts in secret distant ocean locations by the waning light of the moon. Better yet, genetic evidence suggests that great masses – thousands to hundreds of thousands – of eels will gather in a great writhing orgy to reproduce via panmixia (species-wide random mating). And then they die, their bodies sinking to the seafloor even as their young rise as fertilized eggs to the surface to travel the great ocean currents and begin the life cycle anew.

The best guess, based on finding tiny eel larvae, is that European and American eels’ journeys begin and end in the Sargasso Sea, an area in the North Atlantic that encompasses Bermuda and extends a thousand miles to the east. The Sargasso is not a sea but a gyre bounded by currents and full of its characteristic seaweed called sargassum. Breeding areas and timing in the Sargasso for the two species are thought to overlap but remain distinct, with American eels beginning their drift northward before the European eels.

If this is their reproductive home, then their astonishing migratory story goes something like this: After the panmictic orgy, in which each female releases 10 to 20 million eggs, the adults die and the fertilized eggs hatch into flat, leaf-shaped larvae called leptocephali which, drifting northward for months on the Gulf Stream, morph into tiny transparent fish called glass eels when they reach the continental shelf. Some European young will travel over 6,000 miles over two years before reaching their coastline.

A few days after entering coastal waters, the glass eels darken and become known as elvers. Each elver finds its home somewhere in the estuaries, streams, and lakes, and spends its life there as a yellow eel, slowly increasing in size. Females may grow to be four feet long. Yellow eels are capable of breeding after just several years, but some remain for decades. Little is known about how or why eels vary in their breeding behavior, other than that eels grow more slowly in cold waters. One European eel was found to be 85 years old.

The population of American eels stretches from coastal Venezuela and Central America in the south to Greenland in the north. European eels range from Morocco and the Azores eastward through the Mediterranean to the Middle East and northward to Iceland and Scandinavia.

As both species’ final life stage approaches – the epic swim back to the Sargasso – the eels undergo a remarkable set of physical changes. They transform from freshwater fish to deepwater ocean fish. They develop the countershading of ocean fish – dark above and brighter below. Their eyes grow several times larger and more sensitive to blue light, their skin thickens and their fins grow larger, and their swim bladder strengthens in expectation of fighting tough ocean currents. Their digestive system dissolves because traveling to the breeding site is more important than eating. In this stage, they are known as silver eels.

This migration seems to happen at depth as the eels navigate with a sensitivity to magnetic fields and a capacity to follow thermal and salinity differences in deep ocean currents. Like salmon, they’re migrating back to the place of their birth, but it’s fascinating that the breeding ground is defined not by a narrow stream but by temperature, salinity, lunar positioning, and who knows what else in the midst of the open ocean.

But, as astonishing as the adult migration is, it’s the young eel migration that boggles. These tiny, transparent young travel the rough and wild Gulf Stream for many months, navigating (according to an excellent comprehensive hypothesis) by “(i) lunar and magnetic cues in pelagic water; (ii) chemical and magnetic cues in coastal areas; and (iii) odours, salinity, water current and magnetic cues in estuaries.” Smell plays a vital function; the tiny leptocephali are already as sensitive to smell as adult salmon. And the Moon is particularly important, as evidence suggests the young may navigate by the electrical signal given off by a new moon. (Who knew the new moon had an electrical signal?) Furthermore, young eels may imprint on their chosen river’s specific electromagnetic signature “to form a lifelong, rudimentary map to navigate back to the Sargasso Sea as adults.” To summarize, then, the glass eels seem to have a remarkably complex set of navigation tools which they use differently at different stages of the journey.

The question that lingers for me, finally, is how the tiny young distribute themselves so accurately throughout the species’ range. What makes a glass eel aim for Haiti or the Mississippi River or Maine? France vs. Finland? How do the young decide to exit the Sargasso and Gulf Stream and choose which North American or European inlet to migrate into? Unlike salmon, they have no memory of the home they’ll choose. Their genetic “parents” who mingled with thousands of others in a moonless Sargasso orgy will have come from different regions. It can’t be a random distribution determined by the currents, because eel populations would vary widely place by place and year by year.

I hadn’t found any hypothetical answer to this until I read Alessandro Cresci’s comprehensive article quoted above. Perhaps the most interesting idea out there, while still neither confirmed nor complete, is that glass eels may be drawn to pheromones released by the existing eel population in the estuary or river. In other words, this part of their navigation is not done by map but by beacon. Laboratory studies have shown that migratory glass eels are strongly attracted to eel-scented waters. But how far out to sea can this beacon can be detected? Are the glass eels being drawn from a distance to choose one home over another, or are they merely sensing at close range that there is a safe home for eels ahead?

When I asked Cresci about this, he called it the “million-dollar question” and said the likely answer is a combination of factors:

Large-scale ocean circulation, timing of spawning and hatching, and spawning location definitely play a key role in where larvae will end up. Larval movement behavior is also likely to play a key role. However, how leptocephali swim and orient in pelagic waters is totally unknown.. and it’s one of the biggest missing pieces of the puzzle.

And so the mystery lives on for now.

Speaking of safe homes for eels, this wouldn’t be an Anthropocene story if I didn’t detail some of the threats posed by our current civilization to eels and their beautiful lives. The list is long but unsurprising: overharvesting, dams, habitat loss, climate change, pollution. Overharvesting has decimated European eels especially. There’s a very high value placed on glass eels, which are sold to Asia to be farm-raised for the domestic market. Some protections are in place but illegal harvesters provide 90 tons of eels to Asian markets every year. One fisheries manager calls it “by volume, the largest wildlife crime of animals on the planet.” Only 10% of the European eel population remains, and is listed as critically endangered by the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature).

The American eel, in slightly less dire straits, is listed as endangered. In the U.S., only Maine and South Carolina have legal glass eel fisheries. Here in Maine, as elsewhere, fisheries managers have struggled to keep a lid on the harvest of glass eels since the prices paid by Asian markets went through the roof. In 2022, Maine elver fishermen harvested over 9,000 pounds of glass eels with a value of $19.5 million in a matter of weeks. Stories of single-night catches earning tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars are common, as are stories of buyers with trucks full of cash. Unsurprisingly, a gold-rush mentality leads to smuggling, theft, and other nonsense.

Dams have long been brutal eel-killing structures. Not only have they blocked upstream passage to ancient eel habitats for generations, but in those places where eels can get around them and spend years maturing upstream, it can only take a moment for hydroelectric turbines to make mincemeat out of the eels heading home to the Sargasso. The good news is that new fish- and eel-friendly turbine designs allow nearly all fish to pass through safely, though very few of these have been installed so far.

Other habitat loss results from coastal development and severe pollution in waterways. And then there’s climate change, which with its general disruption of fundamental ocean dynamics (temperature, acidity, stratification, currents, biodiversity, etc.), should pose numerous threats to the eels in the decades to come. I worry especially about the likelihood of a shutdown of major Atlantic currents.

You can read more on the grand mystery of eels from Hakai, an excellent environmental magazine focused on coastal stories. For a deeper book-length dive, check out The Book of Eels, by Patrik Svensson, and Eels: An Exploration, from New Zealand to the Sargasso, of the World’s Most Mysterious Fish, by James Prosek.

Finally, thinking about eels and their fate, I’m reminded of a line by the Peruvian poet/fisherman Freddy Guardia in the short documentary, The Ceviche Fisherman: “Nothing stays the way you want it to. That’s why we have memories.”

Lest this seem too somber a note to finish on, though, I’ll quote Wendell Berry again: “To cherish what remains of the Earth and to foster its renewal is our only legitimate hope of survival.” So, with the enduring mystery of eels in mind, let’s do that.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

From Big Think, “I Went to Space and Discovered an Enormous Lie,” a beautiful and important short video by former astronaut Ron Garan, whose time in space observing the beautiful, iridescent living Earth amid the darkness of space woke him up to the reality that ecology is everything and economies are fictions. “We are not from Earth,” he says, “we are of Earth.” From space, he says,

I didn’t see an economy. But since our human-made systems treat everything, including the very life-support systems of our planet as a wholly-owned subsidiary of the global economy, it’s obvious from the vantage point of space that we’re living a lie. We need to move from thinking “economy, society, planet” to thinking “planet, society, economy.”

From the good folks at Birdcast and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, the Lights Out program is vitally important for protecting migrating birds from the fatal hazards of light pollution. Please read and spread the word, especially in support of Lights Out programs in urban areas. Billions of birds are on the move, and hundreds of millions die in collisions every year.

And in related news from the Center for Biological Diversity, the CBD and 29 other wildlife conservation organizations filed a petition this week with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service “to establish a permitting process for commercial buildings to protect birds from deadly window collisions.” The petition is based on requirements under the Migratory Bird Act and “would require building owners to use proven measures to reduce collisions, such as films, curtains or others means that make glass visible to birds.” We know how to prevent many of the one billion deaths of birds who strike windows, but we’re not doing enough of it. This petition aims to change that.

From the Guardian, the US and a handful of other wealthy nations are squandering tens of billions of dollars (with hundreds of billions more in the offing) for unproven climate “solutions” - carbon capture and fossil-based hydrogen - favored by the oil and gas industry. The investments are not only failing to reduce emissions, but they’re propping up the industries that need to be reined in.

And some better news from the Guardian on the decision by South Korea’s constitutional court that the government’s climate law, which does not have binding targets for emissions reduction, violated the rights of future generations.

From the Times, a comprehensive article on the impacts of the widespread habit of spreading sewage sludge as fertilizer, particularly the introduction of high levels of PFAS “forever chemicals.”

Tired of mowing a large lawn? Want to revitalize the natural world that surrounds your home? Stop mowing and rewild your home landscape into a useful, beautiful place for all species. From Minnesota Public Radio, “Native Plants, Lots of Patience,” a story of a couple who did just that for their lakefront house.

Thank you Jason, for your ever-beautiful writings that embrace your readers with quietude during these turbulent times of uncertainty - although Hope feels to be on the horizon - even for the eels.

Who knew? Certainly not I. Eels Must certainly be the most amazing creatures on the planet. Thank you so much for introducing them to us. I am misanthropic precisely because of the damage we are doing to the natural world and its constituent species like these astonishing eels you write so eloquently if. Again, thank you.