Running AMOC

2/15/24 – Our response to the forecast of a likely collapse of Atlantic Ocean circulation

Hello everyone:

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read this week’s curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

As some of you have heard, there’s some serious news about the future of the Atlantic Ocean this week. It has me thinking about our future, certainly, but also about the precautionary principle. So, before we plunge into the ocean, let’s talk a bit about risk, and about our attitude toward the threat of far greater risks.

I often wonder what it would be like to live in a culture whose relationship with the living world was rooted in common sense and empathy. A good description of what I mean comes from the Wingspread Statement on the precautionary principle:

When an activity raises threats of harm to human health or the environment, precautionary measures should be taken even if some cause-and-effect relationships are not fully established scientifically. In this context the proponent of an activity, rather than the public, should bear the burden of proof.

In other words, live responsibly, and always bear in mind that aphorism from medicine: first, do no harm. If a policy or industrial innovation or corporate model seems like it might be a bad idea, don't do it yet. It's not ready. Prove to everyone that its usefulness justifies its harm. Remember that there is still solid wisdom behind the clichés of better safe than sorry, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure, and look before you leap.

When it comes to climate chaos and the rapid loss of plant and animal life that characterize the Anthropocene, what level of risk should we accept? Think of it this way: If you knew that there was a 0.01% chance your child or grandchild would fall off a cliff at the playground, how cautious would you be? If your nephew wanted to take your kid to the park with cliffs, you’d probably insist that he demonstrate they'll both be safe. Increase the risk to, say, a 10% chance, and the trip probably won’t happen.

Now increase the odds closer to 100% and make the Earth our playground. There’s a long and disturbing litany of tragedies we know will occur in a hotter world, even if we don’t exactly know what the chaos and cliffs will look like. If we know, for example, that our continued refusal to rein in carbon emissions and end deforestation would trigger a tipping point that would cause your grandchildren (and everyone else’s kids too) to live in a world without the ocean currents that stabilize climate and sustain agriculture throughout much of the world, what would you do?

Well, here’s your opportunity to decide. There’s a new study providing evidence that a climate-caused collapse of ocean currents in the Atlantic is quite possible in the world that we’re making, has a particular “abrupt and irreversible” tipping point, and could happen in the decades ahead.

The currents we’re talking about here are known collectively as the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, or AMOC. It’s also known as the Atlantic Conveyor, part of the global “conveyor belt” of currents that move and mix ocean waters throughout the Earth’s seas. (I’ve written about this larger system, particularly its Antarctic context, in a piece called “The Undercurrent.”)

We’ve known from previous studies that the AMOC has slowed by 15% since 1950, that it’s weaker now than it’s been in the last 1,600 years, that it stopped abruptly about 12,000 years ago, and that it has done so often in the distant past. The importance of this study is that 1) for the first time, data suggest that a tipping point can be reached after less than a century of slow decline, and 2) nothing in the computer models of a warming world is likely to stop that process. Because the AMOC has already been slowing for decades, the authors of the study could not rule out the possibility of the collapse happening quite soon.

Judging from the media landscape this week, this story is a blip. Even for those of us paying attention, our response so far is to put it on the pile of interesting and scary studies that keep coming out, and to go on with our lives. I include myself here, too.

It’s probably not a coincidence that the Anthropocene is also an age of excess information. Announcements of existential risk pile up, and announcements of fragile, incremental improvements sit in their shadow. Meanwhile, we drive to and from work on a narrow road between cliffs and playgrounds.

I’ll talk about the AMOC and the consequences of its loss in a moment, but I think it’s worth asking why we do what we do and risk what we risk, especially when what we risk is everything. (The “we” in this discussion is only some of us, I know. I’ve written about this troublesome “we” before.)

The short answer is culture, of course. Culture is both bedrock and atmosphere for humans, but like all life that flourishes between bedrock and atmosphere, culture can evolve. Therein lies both problem and solution, since culture can either regulate or encourage carelessness.

What if we had a bedrock belief that human and ecological health were higher concerns than economic growth? What if we enforced this belief through policy, and demanded that risk be assessed not by profitability but by ethics informed by science? What if governance and consumer sensibility both insisted that products and activities be proven safe before being allowed into the market?

Instead, we live in a rapidly warming world in which ice and amphibians are disappearing, the oceans are more acidic and less oxygenated, and in which the majority of the 86,000 chemicals registered with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency “have never received vigorous toxicity testing.” On this latter point, as one expert told the Guardian,

People don’t realize that we actually encourage and even subsidize the production of tens of thousands of chemicals, while imposing essentially no requirements on manufacturers to test their safety. Nor do we ask whether we need the chemical, whether it’s useful, whether there are safer substitutes – or what it’s doing to the environment.

On the largest scale, as determined by planetary boundaries modeling, our production of hundreds of thousands of “Novel Entities” (including PFAS and PFOAs, pesticides and herbicides, plastics and fertilizers, manmade radioactive materials and antibiotics) now raises the question of how much the Earth can tolerate “before irreversibly shifting into a potentially less habitable state.”

That irreversible shift isn’t inevitable, but the fact that we’re wondering how difficult the future we’ve made will be for our descendants tells us how little caution we’ve taken while licensing economic actors to transform the world for their benefit.

There’s a notable level of insanity in fetishizing economic activity because it has a side benefit of helping people, rather than building an economy designed to help people. It’s even nuttier to enlarge that idea to promote endless growth on a finite planet. We forget that the fictions we call economies and corporations are artificial species within the reality we call nature.

With our consent, these entities have turned people into consumers, and turned consumers into products as discardable as what they’ve consumed. What they sell can harm us, without repercussion. In this, the data being scraped from us online resembles the PFAS poisoning our wells and breast milk, the microplastics contaminating our blood and oceans, and the cheap fossil fuels now undermining the stability of planetary systems.

Actually, it just occurred to me, for the first time, that the precautionary principle is firmly at work in our culture. But it’s not on behalf of humans or the environment. Corporations, the artificial intelligences we’ve been living with for a long time now, have adopted the precautionary principle to protect their own health, at the expense of the living world. Our ability to harm them is regulated.

We live in a culture in which corporate well-being is often prioritized, and threats to it are largely neutralized, by policy and laws that force people and the natural world to take on the burden of proof when determining harm. Can most of us live long lives without cancer caused by synthetic chemicals? Can ecosystems and wild animal populations survive the onslaught of profit-driven consumption? Time will tell.

But again, culture can evolve. It can do so quickly, with an election, or steadily, with a generation of activists and responsive politicians. To establish a bedrock belief, though, is a different task. I’m not sure if we’ll ever agree on precautionary risk assessment as a baseline for economic activity. The most likely time for that kind of transition is in the midst of an emergency so dire than our fear unifies us. That time should be now, but isn’t, because too few of us are willing to identify the emergency from this distance.

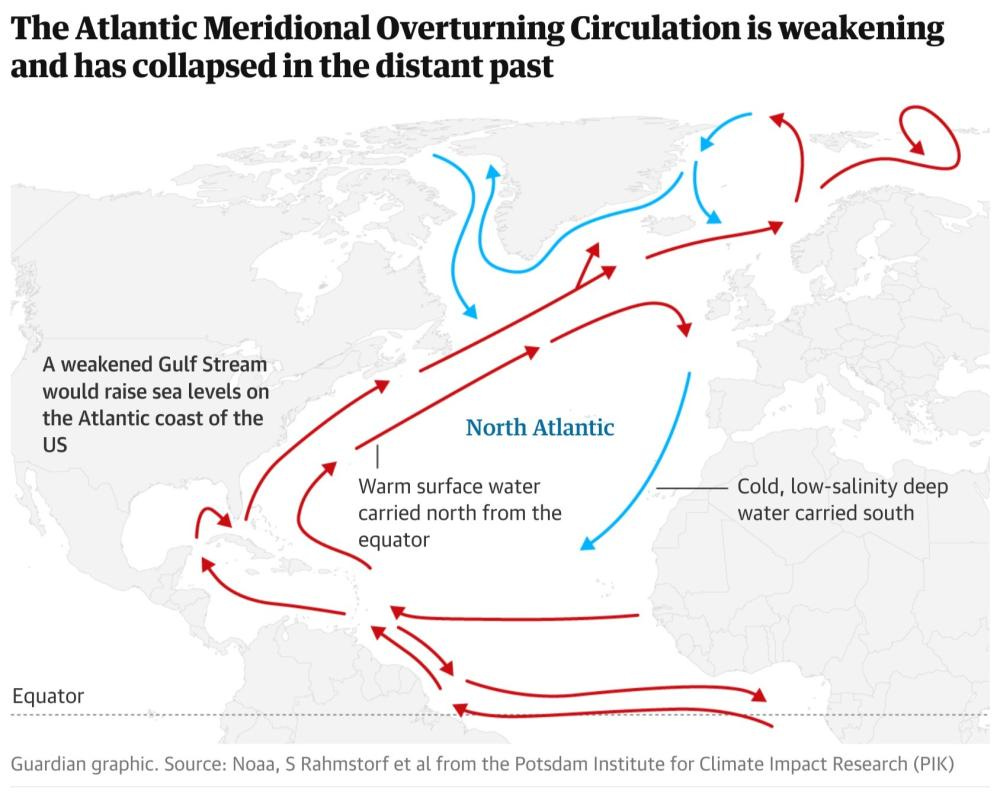

Which brings me back, finally, to the AMOC and its importance. To understand how it works, take a look above at the two visualizations from NASA, and read this concise description from the Post:

Scientists often compare the AMOC to a conveyor belt, driven by differences in water density, which transports water, heat and nutrients throughout the Atlantic Ocean.

It starts near the equator, where the surface of the ocean is warmed by the tropical sun. As that water moves northward, some of it evaporates, which increases the salt concentration — and the density — of the water that is left behind. By the time the water nears Greenland, it has also cooled down, which makes it even more dense.

This cold, salty water sinks to the seafloor, pushing the water that was already down there out of its path. That displaced water starts to flow south along the ocean bottom. Once it returns to the tropics, the water is drawn back to the surface through a process called upwelling, and the cycle begins again.

The AMOC slowdown, and likely collapse, are due to a hotter climate increasing precipitation and river runoff in the Arctic, and accelerating the melting of the Greenland ice cap. That rapidly increasing infusion of cold freshwater, which is less dense, interrupts the Atlantic conveyor’s flow of warm dense water to the north. As that current fails to sink and flow southward, the conveyor weakens and then suddenly stops. The tipping point metaphor here isn’t a light switch we can turn off and then back on. Instead, the Post describes it as someone leaning back in a chair:

As long as they don’t lean too far, they are able to return to their original stable state, with all four legs of the chair on the floor. But if they tilt past a certain threshold – the tipping point – the chair will topple over, and they will be in a new stable state: lying on the floor.

One way to start thinking about the consequences of a collapsed AMOC is to focus on what happens when water, heat, oxygen, carbon, and nutrients stop being transported throughout an entire ocean. The deep Atlantic becomes much less oxygenated, which would prompt a die-off of deepwater species. Without nutrient flow or a vibrant deep ocean, the Atlantic fisheries that feed hundreds of millions of people are upended. As for what happens to plankton and whales, tuna and turtles, seabirds roaming their ancient open ocean paths, migratory eels, and everyone else in the living sea, we can only imagine.

And that’s just the tip of the melted iceberg. Europe, no longer comforted by the warm tropical water pushed northward, would cool by as much as 3° C (5.4° F) every decade. To understand how chaotic that would be, note how we’re struggling to handle the changes from global temps rising by just 0.2° C per decade, less than a tenth the speed of AMOC-induced change. London would quickly be reminded that it’s on the same frigid latitude as the barrens of southern Labrador. Trying to maintain agricultural norms in the U.K., one expert told Inside Climate News, would be like trying to grow potatoes in northern Norway: “You cannot adapt to this.”

These conditions in Europe would echo the Younger Dryas event, a 1,200 year-long freeze-up that turned the U.K., France, Germany and Poland into tundra, and Scandinavia into polar desert.

But a frozen Europe wouldn’t change the larger climate equation. The world would keep getting hotter, and would get weirder faster. In fact, the southern hemisphere and tropical regions would heat up faster because the AMOC would no longer be shifting some of that heat to the north.

The AMOC is one of the planet’s important climate regulators, controlling wind, temperature, and precipitation patterns around the globe. Losing it, according to one analysis the Post cites, could quickly bring drought to as much as half of the world’s growing areas for corn and wheat, and destabilize the monsoons that bring life to Southeast Asia and West Africa. In the Amazon, the rainy and dry seasons would suddenly reverse.

If you think the future of water and food systems for eight to ten billion people look tenuous under current conditions, or if you worry that biodiversity is suffering from our torquing of the climate, wait until we turn off the AMOC spigot.

The entire world would be affected, with sharp differences between regions and increased chaos between them. Tropical trade winds would shift south, bringing permanent La Niña-like conditions: intensifying monsoons in the South Pacific, China, and India, and worsening heat and drought in parts of North America. Imagine more Australian floods and California droughts.

Sea levels in the north Atlantic region, like along the eastern U.S., would increase by up to a meter, as north-flowing water piles up. Warm coastal waters would keep warming, rather than flowing north to be cooled, which would likely intensify the strength and precipitation of coastal storms. Meanwhile, Arctic sea ice would recover and expand as far southward as Ireland and the U.K., helping to mask global heating even as the tropics and southern hemisphere boil. As the Arctic refreezes, Antarctic sea ice decreases and sets the stage for faster glacial loss from the West Antarctic Ice Sheet.

It's tempting to fish for the benefits of an AMOC collapse – more sea ice and reduced methane loss in the Arctic, good glacier skiing in the Alps! – but even with all my catastrophic litany here we cannot imagine the scale and speed of the suffering and chaos that would ensue. Nor can we, not even the scientists who study this, really know the map of what would happen.

What we do know is that we should do everything humanly possible to prevent the possibility of an AMOC collapse. We can’t say with absolute surety that the collapse will happen, nor when it might. But we now have enough evidence to say it’s quite possible, and perhaps in the near future. And this brings me back to the precautionary principle.

Even if there’s only a small risk – 1%, say – of an event precipitating sudden planetary chaos, in which all of our grandchildren and their grandchildren fall off the cliff, the burden of proof should not fall only on the scientists to prove its likelihood without a doubt. Those creating the harm should take responsibility for the possibility. If scientific observation further suggests that the risk increases rapidly – 10% to a 100% – if we maintain our current cultural path, then the burden of proof falls entirely on the industries and governments who created that path. And that’s where we are now.

That last paragraph is a fantasy, of course, when set against the backdrop of how the fossil fuel industry and their pocketed politicians have lied about the known threat of a hotter world these last several decades.

I haven’t mentioned the usual anthropological wisdom that despite our technological advances we’re still myopic, social apes focused on near-term events. We have minds that can imagine longer-term futures but which tend not to defend against those futures until we can see the whites of their eyes. We like to minimize future horrors so we can create present-day comfort. We forget the cliffs to enjoy the playground.

But there’s another wisdom now. Good democratic governance, informed by science and empathy, is defined by its capacity to provide some comfort, plan against some horrors, and build incrementally better futures. In so doing, we surpass some of our simian limitations. Like the rationality of science, good governance does not come naturally or easily to us. These are systems built to make a culture better than our usual behavior in mobs and markets.

And we need these better systems now more than ever, because the Anthropocene is all the evidence we need to see what happens when the precautionary principle has been discarded for so long. If the current version of global culture applied any real importance to science, to the precautionary principle, or to the living world, the long list of climate-related threats that are kin to the AMOC collapse would be an all-hands-on-deck alarm. Yet we still yawn over these science articles, these blips in the news, somehow unaware that our children or grandchildren will be panicking about them in the not-too-distant future. “We are not,” one scientist told the Post, “taking this seriously enough.”

So, what do we do? We do our best to stop the Greenland ice sheet from melting into the sea. How do we do that? We eliminate CO2 and methane emissions and global deforestation immediately. How do we do that? Start right now by ensuring that Joe Biden and every other climate-minded politician is elected. The alternative vote makes all of these risks far greater. Beyond that, we protest and join/support groups pushing for the fastest-possible end to fossil fuels, making agriculture more organic and sustainable, and protecting/restoring forests and wetlands of all types. One recent proposal to do all that just caught my eye this week: Climate North Star. Check it out.

For more on the AMOC collapse, the Post article and the original study are good starting points, as are the Inside Climate News piece, a Guardian article, and a collection of responses to the study from various experts, gathered by the Science Media Centre.

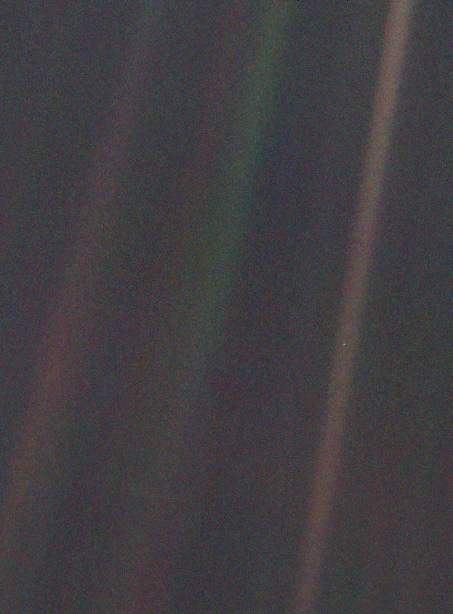

Finally, I’ll close by regifting a Valentine’s Day present handed out by the SETI Institute. The Pale Blue Dot photo was taken by Voyager I on February 14th, 1990, 6.4 billion km from Earth as the craft was leaving the solar system. “Look again at that dot,” Carl Sagan wrote.

That's here. That's home. That's us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives.

The dot is much more than that: it’s the history of life and the very idea of life shining brightly against the emptiness of space. It is also the future of life, a future that we are now defining by our decisions and indecision. We must proceed with wisdom and with caution, because every human and every other species will live out their lives on that dot too.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

From Spaceweather.com, the Earth’s magnetic field might be altered or weakened by the extraordinary increase in satellites put into orbit. Largely due to the megaconstellations of communication satellites launched by Elon Musk’s Starlink and others, “the satellite population has skyrocketed, more than doubling since 2020.” More than half a million satellites are expected in the decades ahead. This is still early research, but the indications are that as satellites burn up on re-entry, their disintegration creates a cloud of “conducting, electrically-charged particles around our planet.” A single Starlink satellite weighs seven million times more than all the naturally occurring charged particles in the magnetosphere, which protects Earth from cosmic rays and solar storms.

From the Center for American Progress, an overview of the remarkable and historic amount of conservation work being done by the Biden administration. Here’s a summary:

in the Biden administration’s first three years, it has conserved – or is in the process of conserving – more than 24 million acres of public lands across the country and has channeled more than $18 billion dollars toward conservation projects. About half of that land – more than 12.5 million acres – was conserved in 2023 alone, marking a dramatic increase in the administration’s pace of land conservation.

In related news from the Times, Pres. Biden has done more to combat the emissions side of climate change, by far, than any other U.S. president. And his initiatives to protect American lands and waters are as robust as any in generations. But voters seem largely unaware of Biden’s achievements, esp. the incredible success of the Inflation Reduction Act. Please spread the word.

Also from the Times, funds from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) will now help states, cities, and communities install solar panels on public buildings (like schools and hospitals) as they rebuild after natural disasters.

From Yale e360, U.S. cities are finally getting serious about parking reform. Why should cities mandate available parking when, as the article points out, “Parking lots are an environmental disaster twice over, consuming vast quantities of materials and land while they subsidize endless driving.” Eliminating mandates for parking spaces around new buildings “help to reduce car dependency, create public and green spaces, and lower housing costs.”

From Rewiring America, not sure how to electrify your life and burn less fossil fuel? Check out their personal electrification planner.

From Mike Shanahan at the Global Nature Beat, another pair of his incredibly thorough weekly updates on biodiversity research and news from around the world. If having a comprehensive source of biodiversity news, both science and policy, interests you, I highly recommend you subscribe to Mike’s newsletter. If it’s news that you can use, I recommend becoming a paid subscriber, as I am.

From Slate, “The Dark Side of Ocean Cleanup Technology,” a dive into the pros and cons of scooping up all those bits of plastic at the ocean surface, which is still a rich habitat for ocean species.

From Hakai, recent research suggests that fertilizing the oceans with iron isn’t the climate solution we’ve hoped it would be.

From Mother Jones, a quick round-up of recent research and conclusions about just how weirdly warm the world has become in the last year.

I'll skip my usual praise other than to say it's remarkable to me how you consistently continue the very high standard you've established in The Field Guide.

The problems surrounding changes in the atmospheric and oceanic transport systems are becoming clearer. The swirling patterns are becoming clearer, the global plant and animal and microbial movements, migrations and spreads are responding and changing.

We already are in a new world and better love it now, for rapidly it will be replaced by yet another. I think it likely, very likely the AMOC collapses in the next thirty years. Another tipping point, tipped. It is again almost certain we will see another collapse- this in the Amazonian forest, our planet's greatest land based carbon sequestration sink- another catastrophe.

Sudden climate crashes have occurred many times in the past-there is no rational reason to suppose we're now immune. A Younger Dryas seems likely for Europe. And if so Putin will be the least of its worries. Or maybe not..?

What figuratively keeps me up at night is the worry that some people will take this situation seriously enough to take decisive action. A good thing, right? No, a catastrophic thing if those people are authoritarian rulers of powerful nation states that listen to their scientists and then decide to preemptively position their own countries for the now probable coming turmoil and upheaval. And they choose violence.

Michael has said it well. I'll only add that this post is another example of why I'm so grateful that you're out in the world thinking and writing, and why I'm proud to be a paying subscriber.