Drinking Ourselves Under the Table

2/5/26 - Our depletion of ancient aquifers, and what comes next

Hello everyone:

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read some curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

Thirsty but Drowning

After nearly five years of writing the Field Guide, I’m often awed by the scale of human transgressions of healthy planetary norms, but rarely astonished. Our supervolcanic scale of Earth-warming emissions, our repurposing of much of the planet’s biological production to feed cows and other livestock, our Pole-to-Pole contamination of rain and snow and sea, and the blink-of-an-eye speed with which all of this has happened: I’ve grown accustomed to such things.

But I can still be surprised, especially by the details. That’s natural, I suppose, when exploring a planet’s worth of impacts. I learn so much every week, about both problems and solutions, as I research these essays.

Here are a few notable things I’ve learned looking into our changes to the fate of water:

Part of the Central Valley in California, a “breadbasket of America,” is 30 feet lower than it was a century ago, because farming has siphoned up so much of the aquifer (underground water) for irrigation. The land is sinking into the space that held the extracted water, and will continue to do so until the water is gone.

One of the largest drivers of global sea level rise is the run-off from irrigating our industrial-scale farms.

As aquifers shrink, glaciers melt, and surface water is overused/misused, many cities and countries are slipping quickly from “water crises” toward essentially irreversible “water bankruptcy.” Some of us are aware of the former, certainly, but far too few of us understand the proximity and calamity of the latter.

Of these, I was wowed by the first, stunned by the second, and deeply worried by the third. Let’s start by taking them each in turn to see what they say about our unbalancing of the watery world.

Aquifers are natural reservoirs of groundwater. Groundwater is the general term for all water that has infiltrated the soil and sunk down deeper into the earth over very long periods of time to create saturated zones. A water table is the line between the saturated zone and the unsaturated soils above it. This subterranean water source feeds forests, seeps into streams and rivers to keep them flowing even when there is no rain, and can be siphoned up by our drilled wells to provide water whenever we want it. The depth of the water varies according to the balance between input (precipitation) and output (now largely human usage and drought).

We now live in a world - have created a world - in which many of these aquifers are being drained much faster than they can recharge, particularly for agriculture and especially where urban development occurs in dry landscapes. We and our wells, which in many places are drilled deeper and deeper to chase the descending water table, have been like drunks on an Anthropocene binge.

Geology and other factors determine whether the land will follow the water down. In Chicago, for example, the water table beneath the city has dropped some 900 feet, but the urban area is sinking only a couple millimeters per year, and some of that loss is due to other reasons. California’s Central Valley, as I noted, has been sinking like a stone into an empty pond.

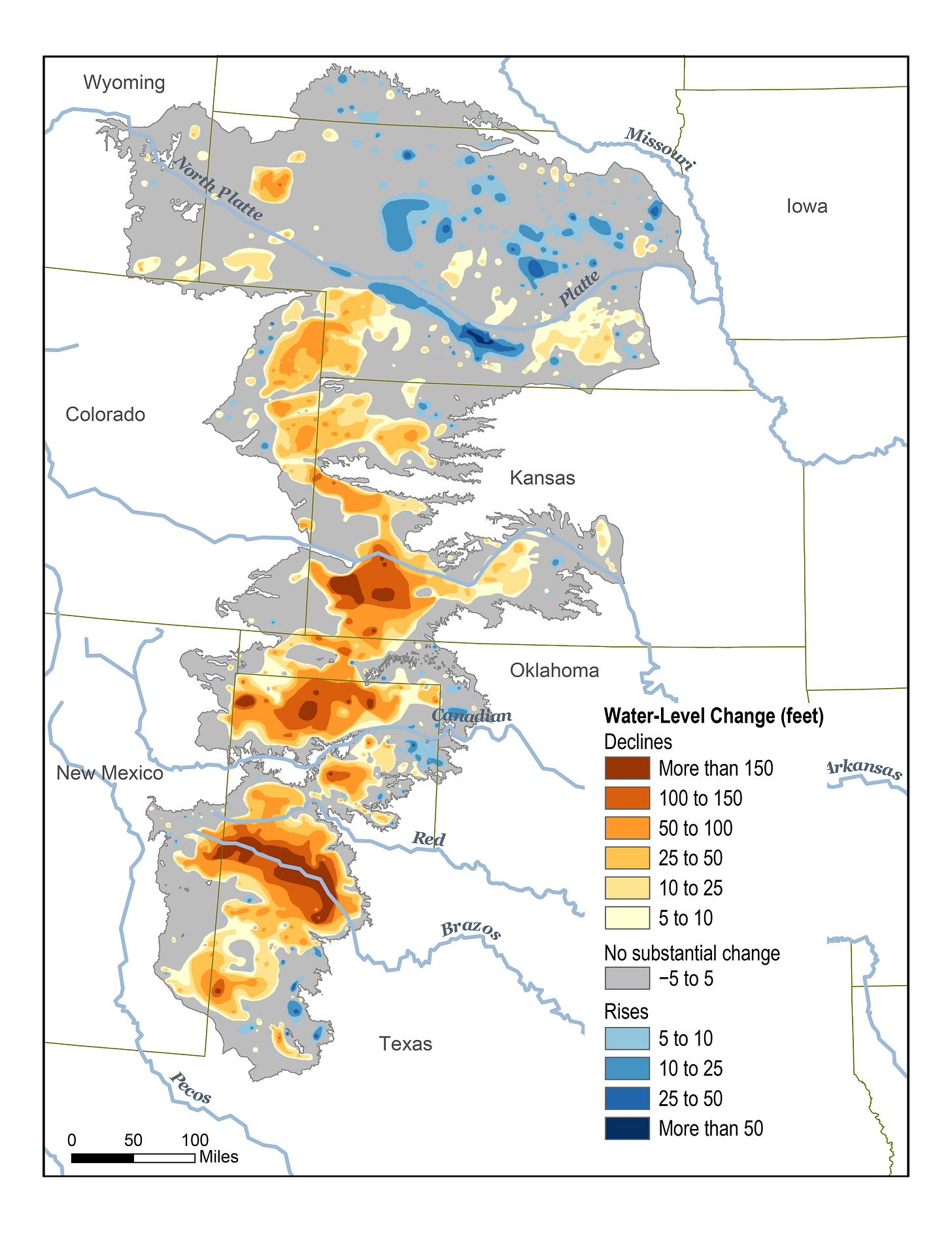

The Ogallala Aquifer, pictured above, underlies eight U.S. states and provides a third of the nation’s water used for irrigation, and land above it has subsided more in some places than others. It’s another “breadbasket of America,” with seemingly endless green circles (like in the photo at the top of this page) turning ancient water into today’s crops. But we’re draining it at eight times the speed of its replenishment rate. Just to cite one region, much of the aquifer under the Texas Panhandle is declining so rapidly that much of it may be unusable within this century. The Ogallala formed in the last ice age, and we seem unlikely to produce another one of those for a while.

A study from Virginia Tech found that 28 cities across the United States are sinking into their groundwater deficits — New York, Houston and Denver, among them — “threatening havoc for everything from building safety to transit,” as ProPublica article says. Elsewhere, Mexico City, and parts of China, Indonesia, Spain and Iran are following their water table down. (The upheaval and violence in Iran right now are rooted in drought and decades of water mismanagement. It’s a sign of things to come elsewhere too.)

As aquifers deplete, forests grow thirsty and degrade into drylands, which in turn diminish the natural water cycle between a greener land and a rain-filled sky. As droughts intensify, lands become more barren, streams and rivers dry up, and the local ecology diminishes. Human occupation grows more difficult, as wells must be drilled deeper for a diminishing resource for which industry, agriculture, and settlements all compete against each other. Closer to the shore, depleted groundwater can be replaced by saltwater seeping in from the sea.

And, strangely enough, those shores are increasingly flooded by all the pumped groundwater that made it down to the sea.

I am astonished by the idea that agricultural run-off is a major contributor to sea level rise. It’s easier for me to wrap my head around the disappearance of another natural resource than it is to imagine the amount of irrigation that’s running downstream or evaporating into the sky and then adding to the oceans that are flooding the world’s shorelines. How can what’s lost from watering our crops possibly rival the volume of input from melting of the Greenland and Antarctic ice caps, from the increased run-off from mountain glaciers, or from the thermal expansion of warmer oceans? And yet it does, as an excellent long-form illustrated article, “The Drying Planet” from ProPublica, explained last July.

The sheer amount of run-off boggled me at first, but that’s a distraction. What matters is the scale of the waste. This is a choice we’re making, rather than insisting on efficient irrigation and limits to the rate of aquifer usage. We’re using water but not managing it.

We are somehow drowning our coastal cities and low-lying island communities with our irresponsible thirst.

Aquifer depletion and sea-level rise are just two parts of our wildly comprehensive transformation of how water behaves on Earth. Literally every aspect of water’s presence - ice, water, vapor - on this planet is being disrupted by our behavior. As we alter the atmosphere and make the Earth hotter, the cryosphere (polar ice and mountain glaciers) has become less stable and begun to disappear, as occurred in the Eocene ~50 million years ago when CO2 levels were much higher and crocodiles lived in the Arctic. A hotter atmosphere holds more water, becomes more turbulent and erratic, and intensifies floods and drought in equal measure. And liquid water, whether resting below ground, flowing through rivers, or gathering in the oceans, is increasingly at the mercy of what heat and storm brew up.

For humans, who are both cause and victim of these transformations, the stability of life for future generations looks less certain. We who now carpet the Earth are as dependent as grass on the reliability of water. Here’s a summary from Yale e360 on an alarming new U.N. report on the “water bankruptcy” that’s occurring around the globe:

The report is based on a new study, published in Water Resources Management, that defines “water bankruptcy” as the loss of natural reservoirs resulting from the unsustainable use of fresh water. Unlike ongoing “water stress” and acute “water crises,” the report explains, “water bankruptcy” is irreversible.

The report is rife with bracing statistics about the growing global water deficit. It notes that more than 40 percent of water for irrigation comes from aquifers that are being steadily drained, and that more than 70 percent of aquifers worldwide are now in decline. Over the past half-century, the world has lost more than 1.5 million square miles of wetlands, an area larger than India, while glaciers globally have shrunk by more than 30 percent.

In total, some 3 billion people now live in regions where water storage is unstable or declining.

“Water storage” isn’t the most poetic or respectful way to describe the water that gives us life, but it does nicely sum up our civilizational relationship to it. As groundwater fades downward, glaciers (which for much of the mountain-filled world act as above-ground aquifers) shrink upward, and surface waters like lakes and wetlands and rivers face persistent pollution and intensified drought, we have to face the fact that we must change how we think about water.

Perhaps the first step is to recognize our failure to reconcile the speed at which we live with the pace of reality.

Mayflies on Dinosaur Time

Here is perhaps the most elegant explanation of the water crisis: We’re not running out of water; we’re shifting it into places that will cause us endless trouble.

Water, after all, cannot under normal circumstances be created or destroyed. We can move it from place to place, or help it transform between its solid, liquid, and vapor phases, but we’re not erasing it in the same way we’ve erased many biological systems that depend upon it.

Aquifers, ice caps, and glaciers are fossil water. Like naturally occurring fossil fuel reserves, these reservoirs of available water formed over timeframes we fail to understand. Thus, we’re draining and melting them in a fraction of the time it took them to form. A drained Ogallala Aquifer, for example, would take an estimated 6,000 year to replenish.

As we extract in mere decades what was gathered over millennia, water ends up where it must on our water planet: the ocean. Imagine, if you will, what kind of time it will take in this hotter, more populated world for that water as snow or rain to rejoin Greenlandic ice or Central Valley groundwater. More to the point, though, imagine how much harder it will be to quench the thirst and ensure the safety of 10 billion people when we’ve relegated the freshwater that sustains us to a hotter sky and a swollen, salty ocean.

As with most of our physical transformation of the Earth in the Anthropocene, the “loss” of water is an existential matter for human societies and the beautiful array of life that has surrounded us in our recent evolution, but it does not alter the long-term capacity for life on this planet. We are likely to bottleneck biological futures if we do not reverse course, but even in the worst-case scenarios life will emerge from the bottleneck to persist and flourish again, as it always has, on a timescale so long that, if the history of life were a book, it would reduce all of human evolution to the period at the end of this sentence.

But the resilience of life across eras and eons is no comfort to a species - us - that lives like a Mayfly in an eternal pond. The marvel and horror of this phase of human history is that we’re an ephemeral species somehow able to disrupt life on a geological scale. Our transformations will outlive us, unless we transform ourselves back into a species who can live within our means. As the great paleontologist and writer Stephen Jay Gould said to my college graduating class - I’m paraphrasing - “Environmentalists are not saving the Earth. The Earth will be fine. They’re trying to save the world so that we can live in it.”

So we need to fix this now, as best we can, in a way that benefits ourselves as well as the fabric of life upon which we will always depend. This means radically altering how we feed ourselves and how we source our water, now and for centuries to come.

Restraint, Rethinking, and Insurance

Finally, how we fix this will be, as with all of our other planetary-scale errors in ecological judgement, a case of using all-of-the-above solutions. Water is life, after all, and so the solution to water crises and water bankruptcies entails learning to live differently. Living differently, in turn, means doing more of some things and less of others. It means putting water management at the center of policy and politics, and it means learning to leave water where it is, to the greatest extent possible.

There will be a struggle to maintain access to water as a human right rather than an investor-owned utility or hedge fund’s profit engine. Regulations regarding water ownership will have to regard scarcity as a communal problem to be solved rather than an opportunity to grow wealthy on the thirst of others. Laws like “the rule of capture” in Texas, that gives landowners the undisputed right to draw up groundwater no matter the consequences to their neighbors, will have to go the way of the dinosaurs.

There will be technological (partial) solutions, of course, in part because that’s the culture we’re stuck with, and in part because (as with solving a too-hot planet) a philosophy of restraint simply won’t be enough. We’ll have to start drinking from the ocean, and that will require applying the clean-energy revolution to an entirely new supply chain. Perhaps we’ll start extracting the vast reserves of freshwater under the ocean floor, though the technology and supply chain issues would be much the same as they are for desalinization.

But mostly, starting right now, this is about refining and regulating how industrial agriculture acquires and uses water. This is too large a topic to close on, really, and I don’t know enough about it, but I’ll just make a few final points, and leave you with an interview to read/listen to.

All agriculture must shift to regenerative practices. They reduce water loss, improve groundwater replenishment, protect biodiversity, and make farms more resilient in a hotter, more turbulent world.

All irrigation, even in those vast circular monoculture croplands sprouting green over the Ogallala, must become as precise and minimal as possible. With new technologies in hand, the days of center-pivot irrigation spouting ancient fossil water from depleted aquifers across hot dry August fields need to end. There’s no excuse now for allowing irrigation water to go anywhere other than directly to the roots of crops.

We have to rethink what we grow and why. There’s more to say about this, but I’m thinking especially of ethanol, for which 40% of the U.S. corn crop is grown. Ethanol is a completely unnecessary fuel, and an utter waste of land, water, and other resources.

Cheese, dairy products, beef and other meat, nuts, and farmed fish are the most water-intensive farm products. Eating less of them, or at least making those supply chains much more efficient, will be vital to reducing our water footprint.

And much more, like irrigating with recycled wastewater, and reducing food waste across food systems.

For an entirely different and fascinating angle, I highly recommend you read or listen to the recent post/podcast from Alpha Lo and the Climate Water Project. He interviews Stephanie Betts, an insurance and finance expert who has shaped her career to try to fix the water problem in agriculture. Her key insights are 1) that insurance is the lever to shift the whole sector from unsustainable to regenerative practices, and 2) that regenerative farms are safer and cheaper to insure than conventional ones. Tilt the farm insurance business to incentivize better practices, and everything changes:

By proving to insurers, investment banks and corporations that regenerative agriculture protects their concerns of food stability and supply chain reliability, Stephanie’s working to turn the insurance industry and global supply chains into engines for water and soil restoration.

Reading this, I thought, was a pleasant surprise.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

From the great Rebecca Solnit in the Guardian, “What technology takes from us, and how to take it back,” an essay that begins with picking blackberries, carries us through the tech-enabled crisis in connecting with each other and the real world, and names the solutions.

The solution to technology is not more technology. The solution to loneliness is each other, a wealth that should be available to most of us most of the time. We need to rebuild or reinvent the ways and places in which we meet; we need to recognise them as the space of democracy, of joy, of connection, of love, of trust. Technology has stolen us from each other and in many ways from ourselves, and then tried to sell us substitutes. Stealing ourselves back, alas, is not as easy as walking out the door. We need somewhere to go and, more importantly, someone to go to who likewise desires to connect.

From Between Two Seas, “to dream an octopus dream,” an encounter with, and meditation upon, the mysterious marvels we call octopuses.

From Inside Climate News, thinking ahead to when gas stations become hard to find. It may be sooner than we think, given how the economics of scale crumble as demand begins to fade.

From Nature Briefs by Rhett Ayers Butler, the decision by Mongabay to begin covering Australian biodiversity issues in much greater depth. The post lays out the case for why this is so important.

From Earth Hope, “The ecologist who dared love Yosemite’s frogs,” a fine tale of one man’s devotion and hard-won victories over 30 years of protecting endangered native frogs. Now, a whole suite of native species are thriving because of his efforts.

From AP News, an excellent if difficult story about the quiet but pervasive spread of PFAS chemicals into the nation’s drinking water. Wells in many rural communities are contaminated, families and towns are unsure what to do or who to trust, and the industry continues to do the bare minimum required, despite the scale of the harm.

This is excellent, and very much the other half of what I wrote yesterday (thanks for the link!), except I certainly couldn't write this because I don't have your wealth of knowledge on the subject. Agreed - as you laid out here, just "finding more water" is as short-sighted as finding more fossil fuels, and what's really needed is a huge infrastructural overhaul (and even a new philosophical approach) in how we use and conserve it - which would be needed anyway, even without the water shortages, because of the way tech companies are currently trampling over existing water distribution agreements so massively in order to fuel their profit-making machines.

When I was a child, my grandparents lived in a tiney house with no running water or bathroom. Every morning, my grandfather would pump 2 pails of water from the well and bring them into the house for the day's drinking and cooking requirements. Rain was captured in a cistern which furnished the water for laundry and washing dishes. A small basin held water to wash our hands in, and was used several times before emptying it out on the garden or the grass in the backyard (No amount of grace could call it a lawn). In our own rural home, we had a bathroom but didn't flush unless it was absolutely necessary, and my mother did laundry for 10 people in a wringer washer and rinsed it in a washtub. Those thrifty habits got ingrained into me, and I've always tried to conserve where I could. (I must confess, though, I flush more often than Mother would approve.)