For the Birds

10/30/25 - Our haunting failure

Hello everyone:

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read some curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

Through a Glass Darkly

I’ll start by stating the painful facts. And then I’ll put the solution in your capable hands.

More than a billion birds die in collisions with windows every year in North America because of our blindness, not theirs. They see the world as it has always been across a more-than-human span of time, in the aeroecological space above fertile soils and within the forested abundance of life. What’s happened is that in the last few minutes (as far as Earth history is concerned), we’ve disrupted that fertility and abundance to create a haunted hall of mirrors to live in and kill with. The birds are the ancient world, and we are a pop-up civilization. Globally, hundreds of billions of birds have died at the foot of the glass through which we gaze out at a violently diminished world.

That’s a choice we’ve made, and continue to make, though we can very easily make the better choice. With almost no effort, we can reduce bird deaths from window strikes to a fraction of the tragedy that now unfolds every day and every year.

When I say “we,” I mean all of us in every kind of building. When I say “almost no effort,” I mean all we have to do is mark the exterior of the glass in a way that makes it seem impassable to birds (while still clear and useful for us). And when I say “a fraction of the tragedy,” I mean that these window treatments - if done right - can reduce the death toll by by 95% or more.

Those of us who worry about birds and windows still tend to feel relieved after the hit - a soft whump of body and sharp tack of beak - if we see the bird fly away. But recent research suggests that even with the best care available from wildlife rehabilitators, only 40% of window-injured birds survive. Without that care, the survival rate is assumed to be much lower. So, as brutal as it is to imagine, we need to remember that most of those birds who survive the hit will not survive the night:

“We’ve all witnessed birds collide with buildings, shake it off, and fly away,” said co-author Mason Youngblood, PhD, of Stony Brook University. “It’s natural to assume that these birds survive, but our research reveals a stark reality — most of these birds die shortly after.”

This research has pushed the estimate of window-strike bird mortality in North American from nearly a billion to at least 1.25 billion deaths. Every year.

There are an estimated 3 billion fewer birds in North America now than there were just fifty years ago, a 30% reduction in my lifetime. That makes it personal, doesn’t it? On my watch, as they say.

Reflections and Tunnels

I wrote on this topic two years ago, in “Life Behind Glass.” But this week’s writing is in service to the miraculous cloud of the fall migration, with millions of songbirds, waterfowl, hummingbirds, and birds of prey sailing over our heads every night. These night angels are visible on radar, and their movements are predicted in extraordinary detail by Birdcast, which expects 144 million birds in motion on All Hallows Eve 2025, mostly moving down the Mississippi Flyway. Back on October 7th, Birdcast estimated that 1.25 billion birds were in motion over us.

And I was also inspired by

and his recent Easy By Nature piece: “Birdwatching Is Having a Moment - And We Need to Talk About It.” Bill writes eloquently and passionately about birds as portal back to the real world, as a way to reconnect with nature:Here’s the truth: The reason birdwatching is stereotyped as “for old people” is because our culture is so dysfunctional it takes most people 50 years or more to figure out what makes for a meaningful life. The answer is genuine connection to other people and nature. Birds are how most people can get there fastest. Birdwatching is not a hobby for old people. It’s one of the most important things anyone can do at any age to improve the quality of their life.

At its core, birdwatching is about focusing less on ourselves and more on the wider world that surrounds us. Training our attention on nature allows us to approach the end goal of birdwatching, which is to be fully present in each moment and to appreciate the birds as they are—to close the distance between you and the bird so that you experience the reality of two lives becoming one.

Of a Yellow-rumped Warbler he’s observing, Bill writes

This bird flew through last night’s darkness, guided by stars, part of a vast river of birds stretching across the continent. He is on a journey that covers thousands of miles, and now he is here— embodied moonlight and stardust, foraging close enough that I can see individual feathers shift in the breeze. For this one moment, our lives intersect. The bird that crossed half a continent and the human who walked half a mile. I can hear the faint click of his bill snapping shut and the whoosh of his wings. His eyes glisten in the mottled light and then, in a flash, he is gone.

Thinking about how to prevent window strikes is your chance to think like a bird, to make that connection that might save avian lives at the same time it enriches your own. Go outside and look at your house with the eye of a thrush or warbler. Is there a reflection that looks like a world you would fly through? Can you see what seems like a shortcut passage from window to window across a corner of the building?

If nothing else, please realize that any window that a bird has hit is telling you that it’s a window that other birds will hit.

I think of all the birds I’ve heard thunk into windows over the years, or whose small cold bodies I’ve found later. Some were migrating down the continents, stitching the land together: Black and White Warbler, Veery, Sharp-shinned Hawk, Cedar Waxwing, and more. Some were our usual suspects, here year-round in the strange maze of worlds we’ve built and unbuilt: Chickadee, Titmouse, Mourning Dove, Belted Kingfisher, and many others. Each feathered corpse is a jewel, a marvel, a piece of the Earth’s fabric we’ve carelessly discarded because we’re blind to its value.

What are they seeing that we do not? They see continuity where we see wall. They see life where we have built death. For us, windows provide a view of the real world we’ve largely abandoned. For birds, windows mirror that world or offer a false path through it. If you were a bird evolved to perfection in relation with the natural world over uncounted millennia, what would you see in these two windows?

Regarding buildings, I wrote this two years ago:

Increasingly, our buildings fill the landscape. Too much of the living world and its mineral foundation have passed through the industrial blender of civilization to become the stuff that forms and fills our buildings. What we leave for birds, and all other life, grows smaller by the day.

We don’t see a tree as birds see it – home, habitat, caterpillar cafeteria – nor do we know the richness of the earth as they do. We neither feel nor navigate the air with their intelligence. The rain is not our bathhouse. So I suppose it’s no surprise that we scarcely think about our architecture as a bird does.

Our buildings occupy the space where forests, wetlands, and grasslands once stood. They provide little in the way of food. They deflect water rather than offering it in leaf-lit drops. And their windows perform a fatal magic trick: They are as solid as stone but allow light to pass through where a bird cannot.

This magic trick is disappearing a billion birds per year, but it doesn’t have to.

Every Window Matters

To the extent that bird strikes are being discussed in public discourse, we’re talking about them as an urban catastrophe, all those tall and well-lit glass high-rises killing birds during the spring and fall migrations. And while that mortality is real and disturbing (particularly the McCormick Place convention center death zone in Chicago that killed tens of thousands of birds), the graphic above shows us what’s really happening. It’s not the glass towers, though they are part of the problem. It’s mostly my glassed-in porch and your living room and our kids’ college campuses and every small-town home or office building across North America. It’s our homes built like border walls within the birds’ homes.

And just as it’s not really a specifically urban problem, it’s also not a problem with height. A study found that 90% of window collisions in Canada occurred in residences of three stories or less.

Maybe only a few birds die against the transparent parts of your home or first-floor office each year, but if most of the 111 million buildings in the U.S. are killing a handful of birds, you can see how the numbers add up. And do we really know how many birds die against our windows at home or work? We don’t hear them, or we’re away when they hit, and the bodies are scavenged long before we happen to look in the bushes around the building. If we don’t know much about birds’ lives, then we also don’t know much about their deaths.

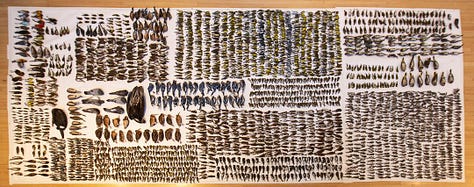

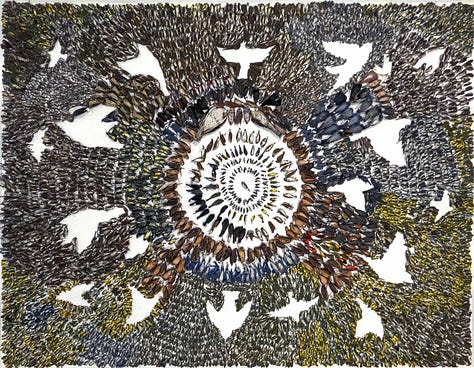

For a compelling vision of those numbers adding up, FLAP (Fatal Light Awareness Program) Canada does its annual “Bird Layout,” using birds collected from the greater Toronto area to demonstrate the all-too-common meeting ground of art and grief. You can see two time-lapse videos of their creation here and here. These are some of the final results:

Make the Invisible Visible

So, what can you do to make the avian world (which is also your world) a better place?

Here are a few principles to start with:

Treat the outside of the glass. Anything on the inside - decals, markings, blinds, etc. - makes no difference whatsoever to how birds see the outside surface. Curtains, shade, and blinds do reduce transparency and the light at night that confuses birds, but that’s not enough.

Windows with exterior screens are safe windows, as long as the screen covers all of the glass. No other treatment necessary.

Start by treating the glass you know or suspect is the most dangerous: Windows near feeders, large picture windows, corner windows, glass balcony railings, etc. You probably don’t need to treat every window.

Exterior window treatments must not allow gaps larger than 2 inches (5 cm) within their patterns. Research has shown that larger spacing will resemble small gaps in bushes or forest that small birds are accustomed to flying through. (The Acopian BirdSavers discussed below are the only exception.) Windows that have muntins (the thin partitions between panes of glass) are not safe enough for birds.

Exterior window treatments should contrast sharply against the dark window, and any markings should be wide enough to be visible to birds at a distance.

Place bird feeders within two feet (half a meter) of a window or more than ten meters away from the house. Bird feeders make window strikes more likely. Research has determined, though, that if the feeder is very close to the house birds are far less likely to build up enough speed to do serious harm.

Move houseplants away from windows, unless those windows are already bird safe.

For the usual residential window treatment methods, I rely on guidance from the Bird Collision Avoidance Alliance and FLAP Canada. Definitely check those sites for a much more thorough discussion of each option, but here’s a quick summary:

Strings: Acopian BirdSavers, designed by a family that’s been using them since the mid-1980s, are an elegant solution that you can either buy or make yourself. Research shows that they reduce collisions by 90%. Nicknamed “Zen wind curtains” for the way they sway in the breeze, the BirdSavers are simply a set of cords (typically dark paracord) hung every four inches from the top of a window frame (all the way to the bottom). I can tell you from personal experience that they’re extremely easy and cheap to make.

Dots: Feather Friendly dots have become a common solution, especially in commercial applications. Based on extensive research, a tight grid of dots (no gaps wider than 4” across and 2” up and down) across the outside of a window will prevent a majority of bird strikes. You can purchase them from Feather Friendly in tape form; you apply the tape and remove the backing, leaving the dots. Or here is a brilliant DIY guide for making a dot pattern with an altered foam paint roller.

Film: You know those advertisements splashed across bus windows, made from a nylon adhesive film that’s opaque from the outside but transparent from the inside? That’s what Wallpaper for Windows and CollideEscape offers in sheets, in a variety of options, including dot patterns, plain white, and clear. CollideEscape also offer an option to upload your own images, which they’ll print onto the film.

Paint or Soap: Grab some colorful tempera paint, paint pens, or soap and let the kids (or yourself) have some fun painting designs across the windows that pose the greatest threat. Or use a stencil of your own design. They’re easy to use and to clean up, and you can update the art whenever you want. Just be sure the art fills the entire window in a pattern tight enough to deter the birds.

There are more serious (and costly) options like replacing a window with frosted glass (which prevents you seeing out), or having windows treated with ceramic frit and acid-etching. These are typically commercial solutions.

Here’s what some of these options look like:

Coda

Finally, I want to note that windows are not the only source of wholesale avian slaughter. Birds are poisoned by pesticides and erased as their habitats - particularly native grasslands - disappear. Wind turbines kill some, though solutions are being developed. Cars and trucks kill millions of birds, of course, just as they (we) kill innumerable other animals on our roads. Just yesterday, in fact, I picked up a dead grouse from the road in front of our house and placed her still-warm corpse at the foot of a tall white pine.

But it’s cats we need to talk about sometime. Cats kill an estimated 2.5 billion birds every year in North America alone. I’ve planned an essay or two on this for some time, and hope to get to it this winter. I may offend some of my readers, but it’s a reality that needs discussing. Stay tuned…

Until then, though, let’s try to think like birds so that more birds can live.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

From Emergence, “Becoming Earth: Experimental Theology,” a must-read essay from Robin Wall Kimmerer. She visits an Oregon old-growth forest and becomes part of its indivisible cycle of life and death, trees and soil and moss and slugs feeding on and dancing with the others. She communes with the spirit of a beloved soils professor and narrates, as always, the meeting-ground between science and spirit.

From

and On the Commons, a beautiful short essay on living with what a balanced world can (and should) provide. Ostensibly about greed, the essay sings instead of plums and otters and larches.From Nautilus, an important and finely-written report on solutions to one of the great but little-reported crises of our time: How to feed billions of farmed fish (that feed billions of humans) something other than fish? Ninety percent of forage fish (anchovies, menhaden, herring, etc) we harvest is ground up and fed to salmon, shrimp, and other farmed fish. But as the author notes, “It is one of the great ironies of our time. To farm the sea, we strip the sea.” These once vast schools of forage fish are a pale shadow of their former selves, and in a warming ocean they need a healthy population to remain resilient. And we need a healthy ocean for our own resilience. (I recognize that the ethics of farmed fish is another difficult matter already.) Thanks to an innovative reward system, multiple plant-based solutions have been devised and tested around the globe, prompting hope that we’ll be able to take pressure off the oceans:

Today, the anchoveta still swim, though in fewer numbers, and the seabirds still wheel above them. But their future, like ours, now depends on whether we will grind them into meal until none remain, or whether we will let them remain what they have always been: the living silver of the sea. “Our shared future becomes more sustainable,” Fitzsimmons said, “only if we can learn to take the pressure off the oceans and create feeds that free us from this dependence.” The future of fish feed is the future of fish. And the future of fish is the future of us all.

From Grist and Foreign Policy, an illuminating deep dive article on why Suriname, one of the few truly carbon-negative countries in the world, is committing to a major oil drilling project in a moment in which fossil fuels are disrupting all of life on Earth. The answer is complex, and the article does a fine job of laying out the narrow optimistic path that Suriname’s leaders are trying to walk.

Two good-news biodiversity stories from Inside Climate News: First, 8000 acres of swamps and wetlands in Alabama are being protected and named in honor of one of the world’s great scientists and conservationists, E.O. Wilson. Wilson grew up exploring the region, and would likely be happy to see the creation of The E.O. Wilson Land Between the Rivers preserve. Second, conservationists and the Asháninka communities of Peru have teamed up to protect, preserve, and give legal rights to the stingless bees with whom the Asháninka have ancient and vital relationships.

From the always excellent Benji Jones at Vox, a long-form article on how the terrible loss of biodiversity in Madagascar, both on land and in the sea, is rooted in poverty and poor governance. Jones focuses on overfishing by subsistence fishers, none of whom want the coral reefs to go silent, but all of whom need to eat.

Thank you for this article! I am sharing it far and wide with my friends who like our painted window dots, but need a bit more encouragement to do something on their own windows. I made a stencil by cutting out a 2-inch grid of 1/4-inch squares on paper (I’m told that a laser cutter would work if you have access to one) and then use a white liquid chalk pen with a quarter-inch nib to paint on the dots. It’s very easy and meditative and it looks kind of cool. I now have peace of mind knowing I won’t hear that dreaded thump. I have seen many birds fly toward our dotted windows and veer away at the last moment, so I know the dots work. Thank you for your great writing!

As I read this, I kept thinking how we desperately need to talk about cats and the damage they inflict and then you mention that this is on the horizon. Thank you! When I talk to people about why their outside cats need to remain inside, these people look at me like I just knifed them. They see the life of an indoor cat to be a greater crime than all the kills the cat will make during a lifetime outside. It’s a hot topic for sure, but one that needs to be addressed. I look forward to reading your article on this.

And, thank you for this beautiful gesture: “Just yesterday, in fact, I picked up a dead grouse from the road in front of our house and placed her still-warm corpse at the foot of a tall white pine.” I wish you didn’t have to do this at all but what a heartwarming act of kindness and respect.