NIMBYism vs. Reality

10/26/23 – What needs doing, what needs protecting, and the tension between them

Hello everyone:

The quote of the week is to honor the dead and the grief of the traumatized here in Maine, in Israel and Gaza, and in Ukraine. And so many, too many, other places. It’s not enough, but it is beautiful. Here’s a short three-line poem from W.S. Merwin titled “Separation:”

Your absence has gone through me Like thread through a needle. Everything I do is stitched with its color.

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read some curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

How I came to write the Field Guide is a winding tale that goes back many years, rooted in my long history of wandering trails and rivers, in my early days reading and writing poetry, and in my deep experience of Antarctica, the wildest place on Earth. But there was a recent catalyst.

Several years ago, my family took point on fighting a 20-acre clearcut for a Walmart-sized parking lot at a botanical garden with Disneyland ambitions here in coastal Maine. Leadership at the nonprofit then was cartoonishly aggressive and dishonest. It was a long, difficult, expensive fight, but it was the right thing to do.

It’s a story I’ll tell someday, but the gist of it is that the parking lots wiped out a huge area of habitat for a network of vernal pools – vital forested wetlands – and posed a risk to the town water supply. Over the couple years of fighting, we won a few skirmishes but lost the battle. The big loser, though, was habitat. No surprise there, since life is being pushed back nearly everywhere by often unnecessary development.

One of my realizations in the aftermath was that if even a “green” organization in a place like Maine could be so destructive, and so blind to their environmental impacts, then the living world needed more voices writing in its defense. Thus the Field Guide.

There was a moment along the way in which some locals in favor of the development accused us of being NIMBYs. The term (not-in-my-backyard) goes back to the 1980s, and has become a common label for people who understand the need for a beneficial project (roads, drug treatment centers, low-income housing, etc.) but who don’t want it in their neighborhood. In the U.S., NIMBYs are often white and affluent – the folks on Nantucket unhappy with offshore wind farms come to mind – who worsen the already common habit of developers and government agencies shunting unwanted or toxic developments (refineries, highways, public housing) into poorer communities.

In our case, it was easy to dismiss the accusation. The botanical garden’s planned development was in our backyard, but we knew it shouldn’t be in anyone’s yard. It was an ego project for wealthy board members and leadership, largely unnecessary and stupidly designed. There was no need to destroy so much important wetland habitat. Our efforts were not to kill the development but to improve it, particularly to reduce the scale of the parking lots which, all these years later, still sit empty most of the year, draining into the vernal pools and public water supply.

I’m thinking about all this because I keep finding references to NIMBYism in the crucial effort to convert the energy infrastructure in the U.S. (and elsewhere) to renewables. For my own sake, for yours, and for the sake of the living world, I want to clarify what NIMBYism is and isn’t in the midst of these Anthropocene crises. There’s a tension between what needs doing and what needs protecting.

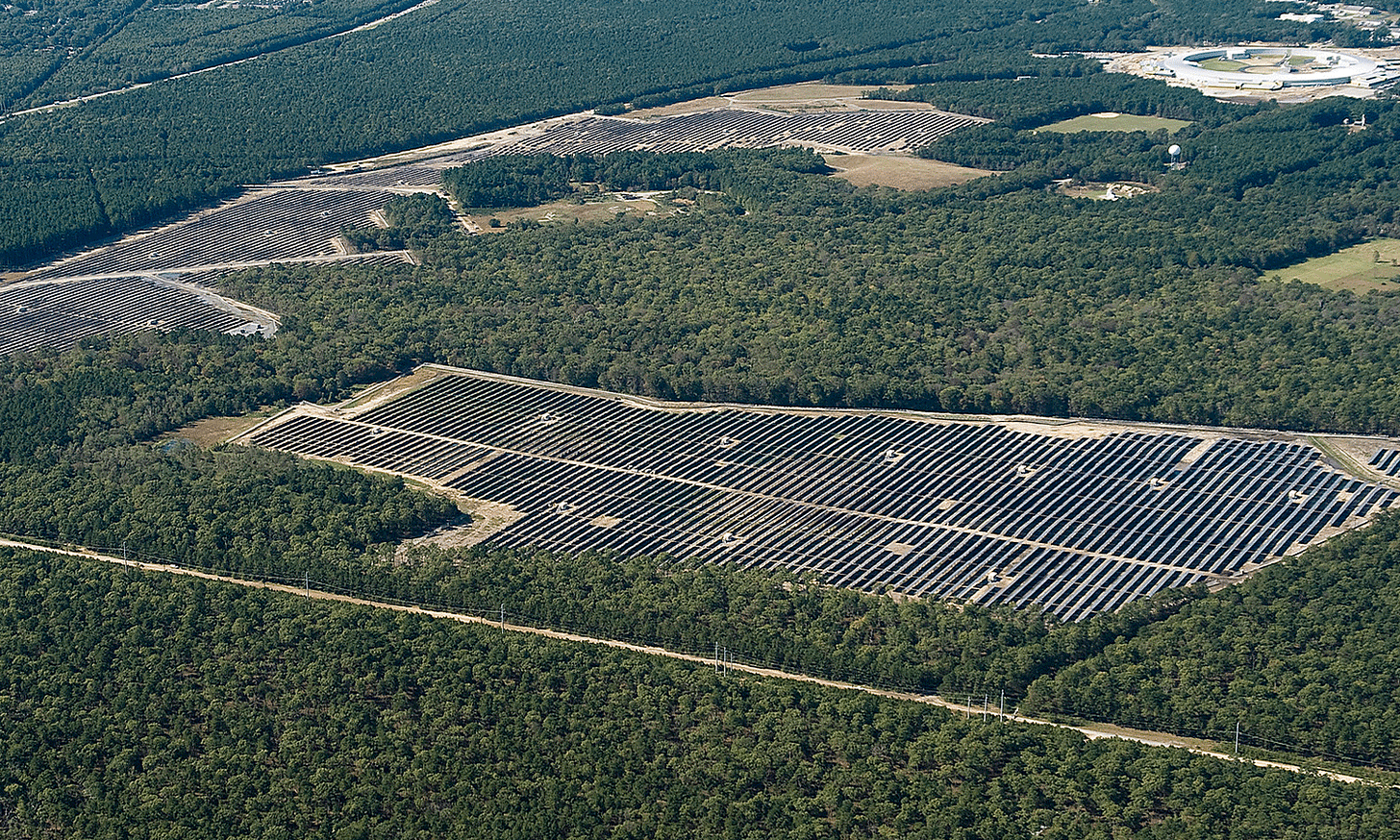

The scale of what needs doing – for example, a massive upgrade of the U.S. electric grid, and a footprint for solar and wind the size of Texas or Arizona – and the speed at which it must be done – in the next several years – is ridiculously daunting. We’re finally making some good progress, in part because of the Biden administration’s efforts, and in part because the price of renewables is now better than the fossil alternatives, but it’s still not nearly enough.

Yet some folks and communities continue to resist or ban solar arrays, wind farms, grid upgrades, and climate-smart urban planning for “aesthetic” reasons or because of often unfounded fears of their impacts. In the rush to rebuild the world sustainably, environmental laws passed decades ago to protect the natural world from destruction are now sometimes used by well-meaning environmentalists as tools to stall or halt necessary projects.

A recent Mother Jones article, “The Green Movement’s Best Weapon Has Become a Problem,” details how environmental laws in California are misused and weaponized to stall work on public housing and other climate-necessary projects. The article makes a point about local officials that I can fully relate to, having failed over two years to convince mine to look at the botanical gardens’ development in the big picture:

Environmentalists know that if climate policy were decided by local officials, we’d burn up the planet. They have every political incentive to cater to annoyed neighbors and none to heed the larger effects of local choices.

And as Katherine Hayhoe of The Nature Conservancy writes, in this civilizational shift to clean energy we’re still facing the same NIMBY and environment justice issues that have plagued the fossil fuel era:

Many people in better-off neighborhoods support clean energy and electrification; yet some don’t want the power sub-station in their neighborhood, the power cable running under their land, or wind turbines visible on the horizon of their view. As Rev. White-Hammond puts it so powerfully, “environmental justice says we need to ask hard questions about who is asked to carry the burden and who receives the benefits.”

In another essential Mother Jones piece, “Yes in Our Backyards,” Bill McKibben writes persuasively that environmentalists like him have spent a lifetime saying No to harmful projects from corporations and governments bent on making selfish decisions,

But we’re at a hinge moment now, when solving our biggest problems – environmental but also social – means we need to say yes to some things: solar panels and wind turbines and factories to make batteries and mines to extract lithium. And new affordable housing that will make cities denser and more efficient while cutting the ruinous price of housing. And – well, it’s a long list. And in every case there are both benefits and costs, all played out in particular places with particular histories.

But there’s a difference, he says, between stupid ideas and necessary ones, even though you might not like either. Which means that some “NIMBY passion will need to be replaced by some YIMBY enthusiasm – or at least some acquiescence.”

The stakes of the effort to stabilize the climate are literally life-and-death, for us and for much of the living world. Just a quick glance at the worsening deluges and droughts, the acidification and slowing currents of the world’s oceans, and the rush toward polar tipping points confirms this. Speed and scale and sacrifice are necessary.

To that end, then, McKibben frames up the need to shift away from NIMBYism based on four elegant principles:

“We don’t live only in our backyard; we also share one.” Our impacts are regional, national, and global, which means solutions at those scales must be local too. A much hotter climate, McKibben notes, will ruin a hell of a lot more backyards than a global supply of solar panels will.

“We don’t live only in our own moment—we’re accountable for past behavior.” The climate work to be done is as much about cleaning up the past as it is preparing for the future. Like it or not, especially here in the U.S., we have a massive carbon debt to pay.

“Idealism involves realism.” We can’t let “lovely goals” obstruct our “gritty needs,” McKibben says. Sometimes an environmentalist with a perfectly valid critique has to look at the real-world math and admit that the best path forward requires a trade-off. Mining for the clean energy revolution, for example, will cause considerable damage and injustice, but it will be only a tiny fraction of what’s caused by the extraction of fossil fuels.

“Emergencies demand urgency.” If we don’t act on climate now, with all available speed and strategies, then the future that’s coming will not allow for much strategy at all. “We will break the planet,” he says, “and those people who come after us will have lost their options (except the option to curse us out).”

You’ll have a hard time finding a better articulation of the conflict between NIMBYism and reality in the face of the climate crisis. McKibben’s principles should be read at every town meeting and urban planning session where climate-related actions are being discussed.

But there’s more to reality than the climate. My sense is that not enough is being said to directly address the tension between the biodiversity and climate crises, and to ensure that all we’re doing for climate is shaped and guardrailed by the needs of biodiversity. That’s what I need to articulate for myself (and for any of you who are interested).

You’ve heard of the IPCC reports and the U.N. Climate Change Conferences (the next one, COP 28, is in oil-stained Qatar next month), but what about the U.N. Biodiversity Conferences or, better yet, the IPBES-IPCC Co-sponsored Workshop on Biodiversity and Climate Change? The IPBES is the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, and the 256-page 2021 report that emerged from their combined workshop with the IPCC produced important statements on how the world should move forward to resolve both crises. But who is listening? And what actions emerged from the discussion?

Why is climate on the front page and biodiversity somewhere near the obits? We can (finally) see the climate bearing down on us, for one thing, whereas the fate of plants and animals is largely invisible to an increasingly urban species. Also, we’re much clearer on how climate hurts us (storms, droughts, heat stroke) than on how the insect apocalypse might. And solutions to the climate crisis are constantly being cast in technological terms – electrify everything, triple the grid, drive an EV, build a better battery – while fixing biodiversity revolves around the quieter, less sexy actions of doing less, buying less, protecting more, and rewilding as much as possible. It’s no wonder we hear more in the media about the possibility of de-extincting mammoths than the creation of Marine Protected Areas, even though the latter might save whole swathes of the planet.

I wrote about the importance of addressing the two crises simultaneously over a year ago in the two-part series “A Flat Tire and a Dead Battery,” the first part of which I updated and republished several weeks ago. In the second part, I quoted Norway’s climate and environment minister on the tension between the crises: “It is clear that we cannot solve [the global biodiversity and climate crises] in isolation – we either solve both or we solve neither.”

The climate crisis is on a faster track to catastrophe, but in the big Anthropocene picture the two crises are equally existential. In fact, an Anthropocene perspective requires a recognition that climate chaos is one part of the larger suite of disruptions to life on Earth.

One essential map for this view is the Planetary Boundaries concept, seen above. We’ve crossed numerous thresholds that are destabilizing Earth systems. And while the rapidly heating climate exacerbates the impact of nearly all the others, and requires the fastest, most drastic action, it is by no means the only ill we’ve released from Pandora’s box.

Looking through an ecological lens at the disrupted world, it seems clear to me that there simply isn’t a good reason amid the rapid loss of plant and animal life on this planet to blindly work on climate action at the expense of essential biodiversity. We’re in a rush for clean electrons, but electrons that erase important species or habitat are neither clean nor sustainable. We have to do both at the same time.

Think of the climate and biodiversity crises as two cracks in the hull of a sinking ship. Climate is the bigger crack, requiring more immediate action, but you don’t bail one part of a sinking ship into another.

The question, then, is where to draw the line. What’s essential to protect? What climate solutions must be built regardless of biodiversity damage? Failing what Bill McKibben calls the existential “timed test” of the cooking climate will wreak unholy hell on the living world, but it’s already a pretty unholy hell for the hundreds of thousands of species being pushed toward extinction; for the billions of birds dead under windows, in the claws of a cat, or poisoned by pesticides; for the disappearing amphibians and insects; and for the severely diminished tropical forests, grasslands, and wetlands, etc.

What kind of guidance do we have – or do we need – for everything from massive federally-funded projects to the community solar arrays being presented to a local planning board? And how do we distinguish between NIMBYs pushing back against necessary things and environmentalists holding the line against poorly-planned renewable energy development?

That’s what I’ll dig into next week.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

From Hannah Ritchie at her newsletter Sustainability by Numbers, a clear and concise explanation of how the electrification of civilization will lead to substantial reductions in energy use. Electrification is efficiency, as she says. The numbers suggest at least a 40% reduction.

From Yale e360, the recent carnage of 1,000 songbirds dying against windows on a single building on a single night in Chicago is inspiring a push to do more about it, everywhere. We fail to realize just how many birds (300 to 900 million) die in window collisions each year, and how big a portion of the overall North American bird population it is. Bird numbers are estimated to have dropped from 10 billion in 1970 to 7 billion now. If we can solve the glass problem – which we very much can – we can boost those numbers at a time when a boost is exactly what they need.

From Vox, an explanatory video, “The Race to Mine the Bottom of the Ocean,” on the extraordinary opportunity and threat posed by plans to mine polymetallic nodules from an area of the Pacific Ocean floor known as the Clarion-Clipperton Zone. To me, the exploitation of this resource will provide mere decades of utility and profit-making at the cost of (literally) millions of years of environmental damage. I wrote about this two years ago in a piece called “Still Digging,” and it’s still worth reading if you want to go a bit deeper.

From the New Yorker, Elizabeth Kolbert reviews two new books that outline how the Anthropocene is largely a function of us extracting, making, and keeping too much stuff. We live our boxed-in lives, forgetting that everything around us has a long dirty trail leading back to a hole in the ground.

From Grist, the similarities between gas stoves and cigarettes aren’t only the hazards for your lungs. They’re the tactics employed by both industries to convince us that the harms don’t exist, despite knowing for decades that they do. It’s all about blowing smoke.

From Project Drawdown, an analysis of the top 20 ways a household can reduce its climate impact. It sounds like clickbait, I know, but this is Project Drawdown, one of the best sources in the world on what actions are necessary to deal with the climate crisis. The biggest impact you can make at home, according to the analysis, is in what you eat and how little of it you waste.

From the Guardian, lawmakers in 22 states have passed laws criminalizing peaceful protests near oil and gas infrastructure after they received money from fossil fuel companies.

From Mother Jones and the Center for Public Integrity, a guide for communities looking to complain to the EPA about environmental discrimination. The process has been difficult, even inscrutable, for decades.

From Anthropocene, new research has found a tantalizing path forward for meatless foods. Fermentation of onions with a particular fungus, Polyporus umbellatus, created a scent similar to sausage. It was liver sausage, but still…

From the Times, how a bottled-water lobbyist has worked to scuttle a Maine bill that would limit the length of contracts the industry can make with Maine towns. The article does a deep dive on the issue of big water companies extracting vast amounts of groundwater and shipping it around the world.

From Inside Climate News, a glimpse into the secret toxic stew used in fracking. Over a decade, frackers in Pennsylvania injected 160 million pounds of chemicals into their wells to facilitate the extraction of hydrocarbons. Part of the stew includes PFAS “forever” chemicals, but we don’t know how much, because these companies’ recipes are protected by laws passed by PA legislators collecting oil and gas lobbying funds. Colorado, though, has banned PFAS in fracking and forced the companies to disclose the chemicals they use. If you want to dig deep into the nightmare of fracking chemicals, start with the good folks at FracFocus, and see what fracking wells in your state might contain.

And finally, apropos of nothing, for the handful of you who might want to geek out on some Antarctic weirdness, a world very few people know much about… Check out a thorough and well-written blog post from Brr all about the electrical infrastructure at the U.S. South Pole station. I’m biased toward all things Antarctic, but it’s fascinating. If you’re looking for a story about sustainable renewable energy, though, you won’t find it here. This is fossil fuel use on the Moon.

Very well said - thank you. Though, as an unapologetic NIMBY, I have to confess that I hope that the "right" thing to do happens somewhere over the horizon. I have a particular concern about densification - I understand it has to happen but all those people stuffed into tiny homes with neighbours within arms' reach and no garden to tend or invite birds and insects and wildflowers into are not going to become the army of environmentalists the world needs. Most of them will become desensitized to the natural world and biodiversity as they stare at their four walls and televisions.

So really we should decide which species we should bother to protect or not, which of the cuter species will be relegated to children’s pajama prints. Maybe some of the kids will ask what happened to that species? Well, sadly kiddo, we need to keep the lights on and the computers and tv running, we all need our personal transport and our out-of-season diets, because humans, we are the most important life on this planet because some story from a couple of thousand years ago told us so and because the other possible stories that might have told us to live as a part of nature and not apart from it were the stories told by savages that decided that they belonged to the land and not the land belonged to them.

Because we believe that keeping that ol’ GDP ticking upwards is a good thing, even though it’s only an experiment that started last century and even though every war is good for GDP and every school shooting is good for GDP but sharing home baked goods across your back fence to your neighbour who you love despite their idealogical differences doesn’t do shit for GDP.

Our response to climate change is to basically pave paradise and put up solar panels and wind farms, all of which are not a solution but a continuation of the fossil fuel industry. If we were serious, where are all battery powered mining vehicles and all the roads built from non-fossil fuels sources, built with battery powered equipment. No, it’s not happening.

Why is the response never to question our energy use, our political systems, our economic system (so detached from reality). Why is Degrowth never an option? Live simpler, more local lives.

I’m in the wrong place here, sorry Jason, I did like your writing but like I said I’m obviously in the wrong place here.