Quieting the Anthropocene Seas

2/16/23 – We should, and can, stop making so much noise in the ocean

Hello everyone:

For anyone concerned about nonhuman life in Ukraine, domestic or wild, there are ways to help. UAnimals, a Ukrainian animal rights group, is focused on rescuing pets, providing food, neutering strays, and rebuilding damaged shelters. Much of Europe’s biodiversity is in Ukraine, and the Ukrainian Nature Conservation Group is doing all it can to protect wildlife, document the war’s impact on the natural world, and preserve conservation data from the bombs.

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read some curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

I did some autobiographical math the other day and realized that, despite having traveled widely, I’ve spent nearly my entire life within a few miles of the ocean. I can scarcely think of a time when I was away from a shoreline for more than a few months. Even in Antarctica, I lived next to the southernmost harbor on Earth.

The ocean is an odd magnet for me, though. I don’t fish or sail, and despite a childhood on Cape Cod I have never liked lying on the beach with other pale flotsam. I’m drawn more to the edges than the sea itself. Here in Maine I canoe between islands, and I walk shorelines. I walk, poke at natural things, pick them up and put them down, collect plastic fragments to throw away elsewhere, and stare out across the water before moving along again. There’s a quiet, happy restlessness in my best relationship with the water’s edge, as if I’m reflecting back the wave energy lapping at my feet. But there’s a calm too, a gift of that open horizon.

We often think of the ocean as a visual spectacle, a vast and restless body for us to gaze upon, swim in, travel across, pull food from, and occasionally look longingly into its depths. (We think this because we increasingly prioritize vision over our other senses, all unused in our relationship with screens.) But the ocean is not the shallow edges we know. It is mostly those dark depths, a deep, dense, permanent night we have scarcely visited, much less mapped. Only the top 150 to 200 meters receive enough light for photosynthesis, and this sunlit zone only makes up 2 to 3 percent of the oceans. The “midnight zone,” starting 1000 meters deep, makes up 90%.

We know a lot more now than when Rachel Carson asked, in her 1937 essay “Undersea,” “Who has known the ocean?” But our ignorance of the ocean is still vast. As Dave Barry put it,

when you finally see what goes on underwater, you realize that you've been missing the whole point of the ocean. Staying on the surface all the time is like going to the circus and staring at the outside of the tent.

But sinking beneath the waves and opening your eyes doesn’t get you very far. The seas are, for their inhabitants, a world often experienced less by sight and more by smell and sound. Fish and sharks might, for example, see a hundred feet, and smell something thousands of feet away, but they could hear a loud noise from miles away. Everything from plankton and corals to orcas and humpback whales rely on their acoustic perception.

As one researcher told the Guardian, “Sound is light in the oceans. It illuminates the ocean for many animals.”

Luckily for us, about 90% of life in the oceans exists within reach, in the sunlit zone. Unluckily for those species, our Anthropocene population and appetites and poor management have led to dramatic overharvesting, habitat loss, and pollution. Those are topics I covered a year and a half ago in a piece called Looking Into the Abyss. The even scarier stuff – the “deadly trio” of ocean warming, acidification, and deoxygenation – I explored in Looking Into the Abyss – Part 2. And I did a deep dive into the latest large-scale threat to the oceans – deep seafloor mining for polymetallic nodules – in Still Digging.

Now I’m exploring solutions for another ocean problem: our excessive noise. From the point of view of life underwater, we are an incredibly loud, obnoxious neighbor. Shipping, fishing, pleasure boating, military activity, seismic exploration, mining, offshore wind farm construction and operation, whale-watching, and much more all contribute to an underwater ambient noise level that makes life difficult for fish, invertebrates, and marine mammals. Our relentless soundscape changes feeding behavior, reduces reproductive success, impairs communication, and generally creates areas where it’s unpleasant to live.

The good news is that much of this can be reduced now. Fixing our noise problem in the ocean is among the low-hanging fruit of the Anthropocene. And unlike other ocean crises, noise is mostly a quick-fix, on/off problem. As we reduce or stop making noise, life in the ocean immediately improves.

Becoming quieter in the sea will increase biodiversity and fisheries productivity in inshore waters and improve the likelihood of survival for the large and charismatic keystone species (whales, dolphins, tuna, etc.) who are essential for a healthy ocean.

Let’s start with a basic point, courtesy of a 2012 report from the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM):

Sound is important to fishes and other aquatic organisms. Many fishes, and at least some invertebrates, depend on sound to communicate with one another, detect prey and predators, navigate from one place to another, avoid hazards, and generally respond to the world around them.

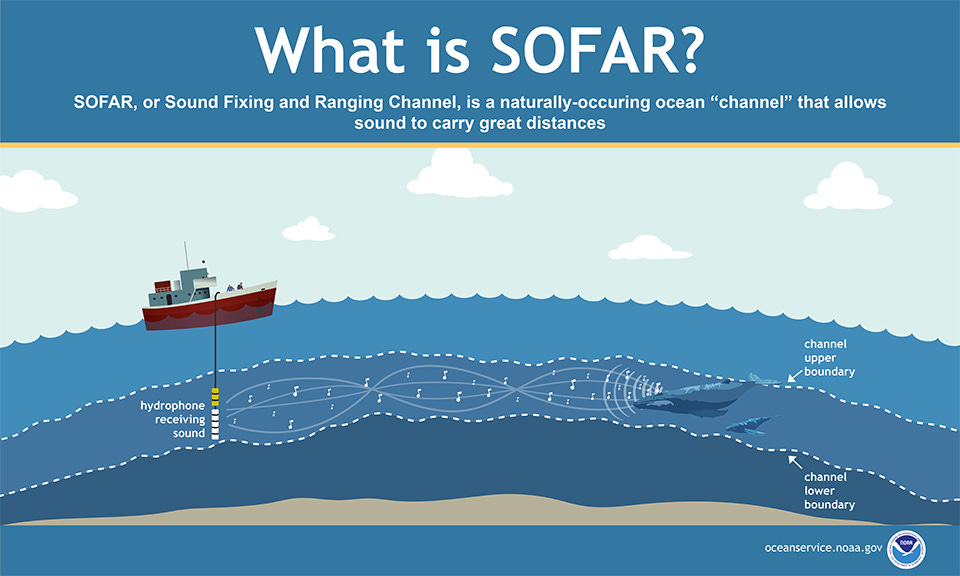

The ocean is also an ideal acoustic environment. Sound travels about 1500 meters per second underwater, four to five times faster and farther than in air. More interestingly, there is a something called the SOFAR channel, a horizontal layer in the oceans (defined by temperature) which acts as a sound wave guide, especially for low frequency sounds. Whale song, and now human signals, can be transmitted like a skipping stone for thousands of miles along this natural phenomenon. The aptly-named “Heard Island experiment” in 1991 emitted a sound off of Antarctica that was heard at sixteen listening stations around the watery world, including Bermuda and Monterey.

To live a normal life, marine mammals, fish, and invertebrates need “acoustic daylight” – my new favorite phrase – which is simply a quiet-enough environment to clearly hear and communicate. (Don’t we all need this?) This is of course particularly true for whales, as an NPR article pointed out:

Humpbacks are a chatty bunch. In addition to their well-known, melodious songs, they make "whups" and other noises, either to coordinate feeding or simply to stay in touch with each other. Sound can travel for miles underwater, sometimes hundreds of miles, much farther than a whale can see. “Whales use sound in almost every aspect of their daily life," [wildlife biologist Christine Gabriele] says. "Studying the underwater sound environment is really important because it helps us see the world the way the whales actually use it.”

I’ve read elsewhere that humpbacks have a musical culture, with new songs sweeping separate populations around the world. But, as the NPR article also noted, that musical culture is harder to maintain now:

“More needs to be done," says Jason Gedamke, who manages the ocean acoustics program at NOAA Fisheries. "When you have animals that for millions of years have been able to communicate over vast distances in the ocean, and then once we introduce noise and have increased sound levels and they can't communicate over those distances, clearly there's going to be some impact there.”

The ocean is a vast, dark place that’s notoriously difficult to study. How do we know that our noise is impacting life in the sea? From some scientific observations of those impact, certainly, but also from opportunities to observe what happens when we become better, quieter neighbors.

After the 9/11 attacks shut down shipping on the U.S. east coast, stress hormone levels in North Atlantic right whales dropped. Twenty years later, cortisol levels decreased significantly when the pandemic kept the annual mob of 73,000 whale-watchers away from humpbacks in Antarctic waters. Pregnant loggerhead turtles in Greek waters spent more time benefiting from the warmer shallows because they were no longer driven away by swimmers. Likewise, water quality, fish populations, and biodiversity all increased in Hawaii’s Hanauma Bay Nature Preserve when it shut down to snorkelers for nine months. And an early observation in the Port of Vancouver as the shutdown began found that noise levels were cut in half, making it easier for local orca pods to echolocate their prey.

The pandemic was an unprecedented opportunity to collect quiet ocean data in Anthropocene seas. Having experienced the shutdowns, you can imagine the underwater shift toward silence, the decrease in cacophony from shipping, tourism and recreation, energy exploration and extraction, naval and coast guard exercises, construction, and port and channel dredging. This experiment in calming the oceans was forced on us by a tragic disease, but we shouldn’t ignore the truth about its benefits, or about our ability to make them permanent.

As one conservation biologist told the Times, “No one can say anymore that we can’t change the whole world in a year, because we can. We did.”

That said, the pandemic effect was neither long-lasting nor universal. A University of New Hampshire study showed that anthropogenic noise on the continental shelf off the U.S. East Coast did not change much during the shutdown. Where commercial shipping was reduced, fishing and pleasure craft apparently made up the difference.

As global civilization surged back into motion, our noisy activity reestablished what ecologists call the “landscape of fear” that other species have to cope with or avoid.

For the worst impacts of our landscape of fear, look at damage in the Black Sea from Russia’s war in Ukraine. A sad and disturbing article from Mongabay about the ecocidal impact of the war explains that an armada of Russian ships and submarines with powerful sonar, not to mention incredibly loud explosions from the bombing of ships and ports, killed thousands, perhaps tens of thousands, of dolphins and other cetaceans. They began washing up in unprecedented numbers immediately after the war began.

There was simply no place for the dolphins, with their incredibly sensitive hearing, to hide. The ocean transmits sound incredibly well, especially deep, low violent sounds. I imagine the dolphins’ plight as holding a stethoscope up to a jackhammer. Such noises cause physical damage to marine animals’ ears and flesh. No one knows what the final result will be, but the war is certainly removing far too many keystone predators and likely destabilizing the Black Sea ecosystem, already at-risk, for generations to come.

What’s happening in the waters off Ukraine is particularly ugly, but it’s only a more extreme version of the violent soundscape in our Anthropocene war on nature. Imagine the din that accompanies the other harms resulting from constant ship traffic, bottom trawling, seismic exploration, sonar searching, pile driving, and dredging to extract minerals, to name a few.

How bad is the problem globally? It’s hard to say with precision, because the ocean is vast and the research is underfunded, but we know enough to know we should be changing our behavior. And we’ve known it for a while. As a 2021 Guardian article noted:

The damage caused by noise is as harmful as overfishing, pollution and the climate crisis, the scientists said, but is being dangerously overlooked. The good news, they said, is that noise can be stopped instantly and does not have lingering effects, as the other problems do.

That article was based on a study called “The soundscape of the Anthropocene ocean,” which analyzed over 500 studies on the impact of human noise on ocean life. Around 90% of the studies measured significant harm to marine mammals like whales, seals and dolphins. 80% of the studies noted impacts on invertebrates and fish. The Guardian article cited some details:

The most obvious impact is the link between military sonar and seismic survey detonations and deafness, mass strandings, and deaths of marine mammals. But many uses of sound can be harmed, such as the hums that male toadfish use to attract females and the honks that cod use to coordinate spawning.

Baleen whales produce calls to help group cohesion and reproduction that can travel across ocean basins, and humpback whales sing complex mating songs that have regional dialects. Sperm whales and various dolphins and porpoises use sonar to echolocate prey. Other animals use sound to feed: some shrimps produce a “snap” sound to stun prey.

Over the past half century, the steady increase in shipping has made the amount of low-frequency noise on major cargo routes more than 30 times worse. It’s doubled every decade since the 1960s. There are at least 60,000 commercial vessels at sea as you read this. That’s a mindboggling number, but it’s only a partial accounting, since it doesn’t include some of the loudest offenders, like military ships and oil rigs, nor the vast numbers of local fishing and pleasure craft. For an astonishing real-time glimpse of just the commercial vessels, though, you can monitor them at Marine Traffic. You can zoom in on any place on Earth where ships are sailing, and click on the icons for each of the many thousands of vessels to learn more:

Remember the cheerful notion of “acoustic daylight”? The noise created by the legions of ships has been described as an “oceanic smog.” Coastal waters and oil/gas exploration zones are generally the noisiest areas, often dominating the natural ambient soundscape. Our low-frequency wall of sound polluting the oceans comes from the ships’ onboard machinery, the rippling of water around the hull, and especially from the propeller.

Remember that because sound travels so well underwater shipping noise is not restricted to shipping channels. It radiates outward. For life underwater, the main problem from the continuing increase in noise is that it masks the natural low-frequency sounds of the ocean, making communication difficult. This impact is worsened in areas where populations are in decline for other human reasons.

As fish, invertebrates, and mammals are less able to speak to and hear each other, the less successful they’ll be at fundamental activities like socializing, feeding, avoiding predators, and spawning. Scientists working around the Great Barrier Reef in Australia, for example, have learned that consistent motorboat noise can double the mortality for fish unable to hear predators.

And then there are seismic airguns, used by the oil and gas industry – and in scientific research – to map the sea floor and the geology deep beneath it. Long rows of airguns are towed behind a vessel, releasing explosions of compressed air. These sounds are as loud as a jet at takeoff, and are emitted every ten seconds, 24 hours a day, sometimes for weeks at a time. This has been going on for decades, with each blast audible up to 2500 miles away.

One decade-long study found these sounds audible throughout much of the Atlantic Ocean up to 80% of the time over the course of a year. The disruption for whales is obvious, but the impacts reach the bottom of the sea and the foundation of the food chain, with one study finding huge impacts on zooplankton (e.g., krill larvae and copepods):

The team found that zooplankton abundance dropped by 64% within one hour of the blasts. And the proportion of dead zooplankton increased by 200–300% as far away as 1.2 kilometres — the maximum distance the researchers sampled. This suggests that the impact of the blasts could extend well beyond such distances…

I’ve talked here mainly about low-frequency sound, but the high-frequency range has its own problems. Sonar in particular is ubiquitous on military, research, and cargo vessels, on trawlers and lobster boats, and maybe even on your little fishing boat. Fish-finders, echo sounders, fishing net control sonars, side-scan sonars, multi-beam sonars, and other sonars for mapping the seabed topography are constantly searching the ocean, and while the high-frequency sounds don’t travel far and are above the hearing range of most fishes and invertebrates, there are perhaps hundreds of thousands of them in service, and they are a disturbance to some fish, like shad and menhaden.

If I’ve given the impression that the ocean noise problem has much to do with the particular sensitivities of sea life, it’s worth remembering that humans can be killed by noise as well. The shock waves from explosions wreak havoc with the body. It’s happening in Ukraine right now. Humans, dolphins, fish, and zooplankton are all soft-bodied creatures in a hard world.

It’s easy to feel that Anthropocene noise is happening in the deep ocean, at some distance from our daily lives, but it’s not that simple. Every time we board a ship, drive a car over a coastal bridge, or sit in a plane taking off over the water from a coastal airport, we’re being noisy underwater. When we use energy from offshore oil and gas, or offshore wind farms, we’re being noisy underwater. And when we eat fish caught by bottom trawlers, or any fishing boat, that’s us too. I don’t mean to inspire guilt. Rather, I mean to explain that, as with so much in the Anthropocene, we’ve been trapped in the choices offered by an ill-conceived civilization.

But as I’ve mentioned a few times so far, there are easy ways to reduce the noise and its impacts. And there’s some good news on the regulatory and technological fronts too. Most importantly, there’s ample evidence that ecosystems bounce back immediately once we become quieter neighbors. We have solutions for this problem. And that’s what I’ll talk about next week.

For now, I highly recommend you watch this excellent, thoughtful video from Vox. It will tie together everything I’ve just told you.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

Excellent news for marine conservation. The Great Bear Sea, a new marine protected area along the coast of British Columbia, will be one of the largest in the world.

From David Wallace-Wells at the Times, an interview with Greta Thunberg. She is as honest as ever about the uselessness of people in power to get the job done.

From Reasons to be Cheerful, the pushback against seed-company monopolies by creating open-source networks of seed growing and distribution. For the avid gardener and anyone else who understands the calamity created by the commercial patenting of seeds, this is important news.

From Inside Climate News, the really positive news that wind and solar power production is already cheaper to build and operate than coal power plants. This should be the death knell for coal power in the U.S.

From The American Prospect, the good news and challenges facing the necessary heat pump revolution. The article does a deep dive on Maine’s best-in-the-nation policies and strategies.

Brilliant! Distressing. Reinforced my curmudgeonly dislike of our own species. Let's get off this planet, move to Mars and let this planet heal itself up. We're so stupid, it's painful..

From one pale flotsam to another, this is brilliant. I especially appreciate the good news links following the incredibly alarming and detailed information on ocean noise pollution. Thanks Jason.