Save the Salamanders, Kill the Gerrymanders

7/7/22 – A healthy environment needs a healthy democracy

Hello everyone:

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the post to read this week’s curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

From any perspective, not least an environmental one, it’s hard to know where to start (or end) a conversation about American politics these days. The Supreme Court, now a leaky ship leaning hard to starboard, just issued a spate of major decisions that demonstrate a bizarre and blinkered determination to weaken the federal government’s capacity to protect human rights, regulate business, and cope with the Anthropocene. States’ rights are a vital pillar of American democracy, but I don’t understand how any rational jurisprudence can set states’ rights above human rights.

The Court’s decision to limit the EPA’s ability to regulate greenhouse gases may well prove quite effective in keeping the U.S. from meeting its climate obligations. The cascade of suffering for natural and human communities around the globe that may result from that failure are difficult to contemplate. But the EPA expected the ruling and is working on alternatives.

Perhaps there will be a backlash against these conservative rulings, as Bill McKibben recently wrote in a post titled “Be the Backlash!” in his Substack newsletter, The Crucial Years. He notes that these decisions on Roe and climate and gun regulations are so extraordinarily unpopular, even with many Republicans, that the midterm elections this November could prove to be a watershed moment in politics. If in 2023 the Senate and House are suddenly run by majorities looking to codify into law the rights and regulatory capacity that the Court has taken away, then it certainly would be a sign of the American political pendulum swinging back to center.

That would be lovely. To get there, though, the midterm elections must run smoothly and legally in the midst of the electoral crisis being fomented by those cynically or unwittingly caught up in the Big Lie about the 2020 election. That’s a tall order, given that legislatures around the nation are busily passing legislation to make access to voting more difficult and the election outcome less fair at the same time they’re working to lock in the kind of cultural shift the Court has enabled.

Some of you may be wondering if I’m straying too deeply into politics in a newsletter devoted to mapping the problems and solutions of the Anthropocene. Believe me when I say that I’d much rather be talking about salamanders than gerrymanders. And for the most part, I will, but my goal with the Field Guide, as always, is to help readers see the human-transformed Earth as it is, and to give some context for our actions that have brought us an addled climate, an increasingly acidic ocean, and a 1000-fold increase in the extinction rate. Politics, though it is the shallow end of the civilizational pool, is often that context.

Politics is the fabric of cultural power, whether brutal or generous, fair or unfair, democratic or tyrannical. When power rests in the hands of representatives who truly represent the balance of views of the American majority which wants a healthy environment, then legislation will reflect that balance. Moneyed interests and their political proxies have, in recent years, made that much, much harder to achieve.

I’ve been wondering how to phrase all this in a simple sentence, and then the sentence showed up in my mailbox. A bulk fundraising mailer from the League of Conservation Voters arrived emblazoned with this line: “There’s no healthy environment without a healthy democracy.”

Some of you will recall that I wrote a long piece called “Politics All the Way to the Horizon” back in January about whether democracies were any better suited than authoritarian states for dealing with environmental crises (spoiler: they are, though on the climate front the evidence is still spotty). This time, I’m going to be a bit more specific and zero in for a moment on what I’ve often thought has been the weakest link in our electoral politics – partisan gerrymandering – and then zoom back out to discuss its place in the Anthropocene.

There are a lot of leverage points in the electoral landscape that those of us looking to strengthen democratic norms could focus on: allowing Ranked Choice Voting in all elections, passing the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, making Election Day a national holiday, completing the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact to outmaneuver the outdated Electoral College, or reining in the disinformation media ecosystem, just to name a few. (Or hell, maybe we should replace the money-plagued, two-party-limited election of representatives with a random selection by national lottery.)

For me, the extremism and polarization in today’s U.S. politics owes a lot to partisan gerrymandering. As an article at FiveThirtyEight explains, I might be wrong to put it at the top of my list, but I think we can all agree that it’s high on the list.

Partisan gerrymandering is the legislative shaping of political districts so that political parties can choose their voters rather than campaigning honestly to convince a variety of voters to choose them. Generally the process takes two forms, “cracking” (spreading the opposing party’s voters across several of your districts) and “packing” (concentrating those voters into one district to minimize their voting power). FairVote, a nonprofit working to “research and advance voting reforms that make democracy more functional and representative for every American,” defines it this way:

Gerrymandering is the act of politicians manipulating the redrawing of legislative district lines in order to help their friends and hurt their enemies. They may seek to help one party win extra seats (a partisan gerrymander), make incumbents of both parties safer (an incumbent-protection gerrymander) or target particular incumbents who have fallen out of favor.

Those engaged in gerrymandering rely heavily on winner-take-all voting rules. That is, when 51% of voters earn 100% of representation, those drawing districts can pack, stack and crack the population in order to make some votes count to their full potential and waste other votes. Gerrymandering has become easier today due to a combination of new technology to precisely draw districts and greater voter partisan rigidity that makes it easier to project the outcome of new districts.

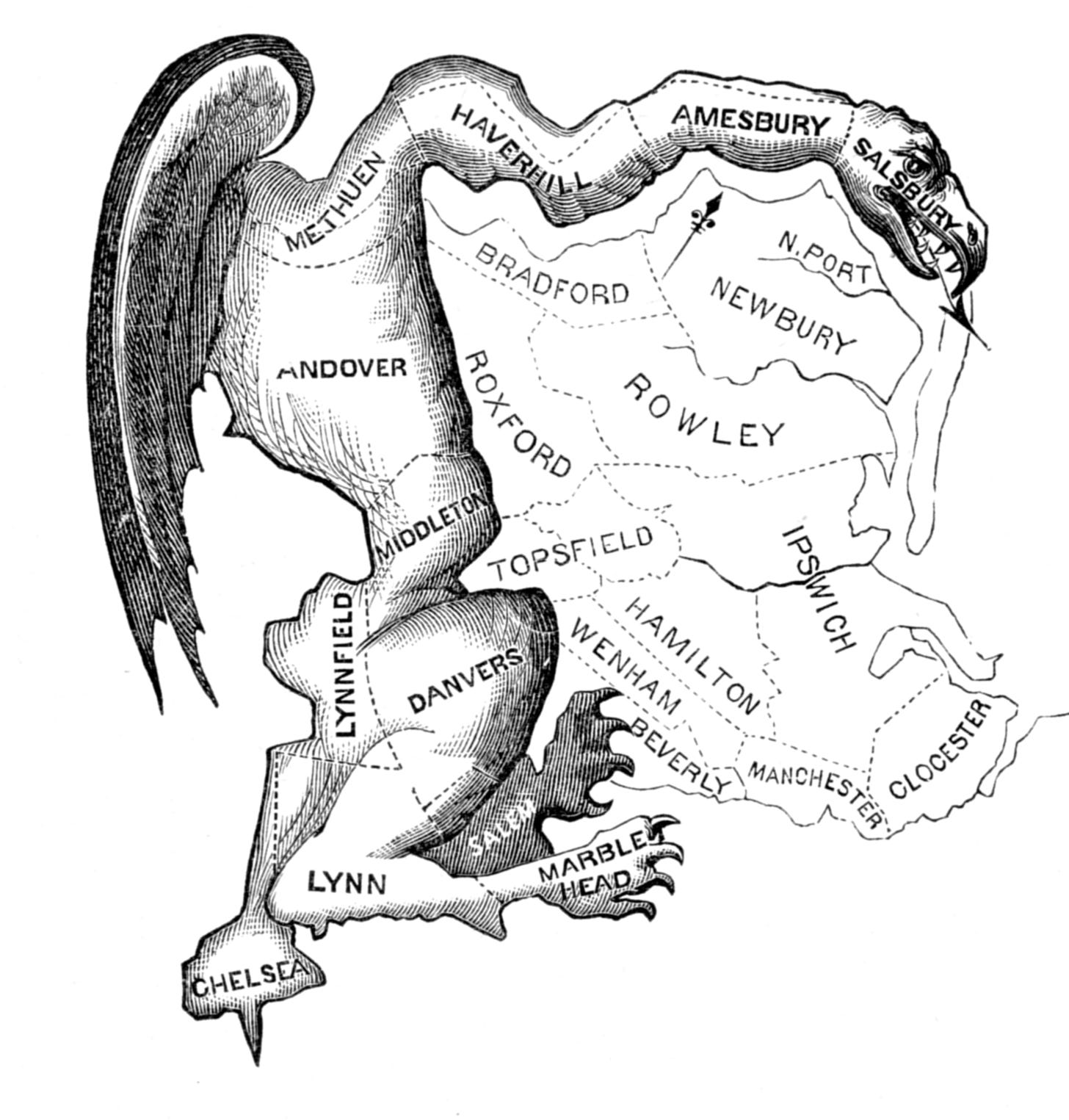

The term originates in the drawing of a vaguely salamander-shaped district north of Boston in 1812, an act approved by Massachusetts governor Elbridge Gerry. The press created a portmanteau word – the Gerry-Mander – and it caught on, thanks in large part to the cartoon that opens this week’s writing. And thus was born a political beast…

(I should note that not all electoral salamanders are gerrymanders, i.e. not all gerrymandering is partisan. Some bizarrely-shaped districts are created to strengthen minority representation or simply to create a balanced and competitive district.)

A partisan gerrymandered district is a non-competitive district. Non-competitive districts in the U.S. are now far more common than competitive ones, which means that legions of voters live in districts where their vote is deliberately wasted. And they know it. Both the gerrymandering and the voter apathy (or anger) that it creates are corrosive to our electoral politics.

Back in 2006 a Mother Jones article with the title, “Gerrymandering: Why Your Vote Doesn’t Count,” quoted a Democratic Representative in California about the economics of cheating the system:

It turns out that redistricting is easier and cheaper than actually campaigning. In 2001, U.S. Rep. Loretta Sanchez (D-Orange County) admitted that she and her colleagues paid $20,000 to map-maker Michael Berman to preserve their seats. “Twenty thousand is nothing to keep your seat,” Sanchez said. “I spend $2 million (campaigning) every election.”

Democrats have thoroughly engaged in gerrymandering throughout the last two centuries, and were busier with it than Republicans in the late 20th century – Maryland still had its “broken-winged pterodactyl” until early this year – but it’s worth remembering that the Democrats of the 19th and early 20th century were the pro-slavery/Jim-Crow/pro-business/anti-union party of their era.

Now it’s 21st century pro-business/anti-union/fossil-fueled/evangelical and sometimes race-baiting Republicans who have mastered the cynically reshaping of districts to control elections. With the REDMAP Project they elevated the deviousness to a degree that many believe has undermined the American political experiment. They made a massive and unexpected $30 million push to win state legislative elections before the 2010 U.S. Census. Why? Because controlling state legislatures meant they controlled the redistricting which followed the census.

With cynical, slash-and-burn negative campaigns, REDMAP won some 700 state seats and flipped 20 legislatures from blue to red. An excellent New Yorker article by Elizabeth Kolbert explains how successful the redistricting effort was in Pennsylvania:

So skillfully were the lines drawn that in 2012 – when President Obama carried Pennsylvania by three hundred thousand votes and the state’s Democratic congressional candidates collectively outpolled their G.O.P. rivals by nearly a hundred thousand votes – Republicans still won thirteen of Pennsylvania’s eighteen seats in the U.S. House of Representatives.

It’s yet another example – as if we need another – of how good politics is bad ethics. For the full REDMAP story, you can read David Daley’s book, Ratf**ked: The True Story Behind the Secret Plan to Steal America’s Democracy.

But let’s try to ignore the political parties for a moment and instead draw a straight line between the increase in gerrymanders and the decrease in salamanders… i.e. the environmental consequences.

First, non-competitive districts make bad politicians and polarized politics. More than 85% of House seats are safe seats. According to FairVote, “in 2020, the median margin of victory in a congressional race was over 27 percentage points.” And a 2020 study found that candidates in these races tend to have “weak résumés” and be more polarized. In the campaign and in office, politicians from unfair districts don’t have to pursue a balanced agenda to serve all constituents. In fact, it’s increasingly likely they will be punished for compromising with the other party to pass legislation. Political survival requires avoiding a primary challenge from someone more polarized than they are. In other words, unbalanced districts breed unbalanced representatives.

Distorted outcomes and wasted votes are corrosive to democracy. In the 2012 election (after the 2011 redistricting), Democrats received 1.4 million more votes in House elections, yet Republicans won control of the House, 234 to 201. Voters in these districts are more likely to become less engaged or more enraged, increasing apathy and polarization at the same time. Worse, many of the communities being packed or cracked are urban communities of color whose loss of representation amplifies the environmental racism which has historically made their neighborhoods less green and more toxic.

Meaningful environmental legislation usually requires either landslide elections of progressive candidates or cooperation across political lines. When elections are heavily tilted to anti-environment conservatives, and when there’s no political pressure to compromise, little gets done, even amid the consequences of a rapidly warming planet. The money behind these successful conservative initiatives – REDMAP, the appointment of intensely conservative judges, and now the cynical Big Lie – is coming largely from business interests on a decades-long campaign to limit the capacity of the federal government to regulate industries, especially the fossil fuel industries pushing back against the climate change agenda.

All of which means that two main sources of energy in politics these days are conservatism and chaos, neither of which is even slightly conducive to rational environmental policy. The more chaos in politics, the less progress toward reimagining culture to cope with a warming world. We should be turning away from fossil fuels, rewilding landscapes, rebuilding wetlands, limiting the production and use of toxins, and investing heavily in climate solutions that also protect and rebuild biodiversity.

We all know that there is a massive but less-organized pool of energy across the nation (and the world) to turn the ships of state in the right direction, especially in terms of coping with and combating climate change. These moves by industry-funded conservatives to stymie fair elections and hamstring federal regulations are strategies deliberately meant in part to oppose that energy.

As I mentioned at the top, citing Bill McKibben, this can all change direction with one good election of a slate of candidates determined to deal with the world as it is, to prepare and adapt to a changing globe, to rebuild a tattered and poisoned American landscape, and to respond to the Supreme Court’s half-witted attempt to turn back the clock on the rights and federal power that most Americans value. That election can only occur if everyone unhappy with the successes of the far right in electoral and judicial matters – that’s a majority of Americans – motivates, organizes, and votes.

With his trademark gritty optimism, McKibben cites the origin story of the legislation that the Supreme Court just wounded in its ruling against the EPA:

To understand the possibilities, consider the Clean Air Act itself. It was signed into law in 1970 by Richard Nixon—a few months after the first Earth Day brought 20 million Americans into the streets, energy that carried over into the midterm elections. The Earth Day organizers targeted a ‘dirty dozen’ congressmen—and beat seven of them. Their political clout established, they were able to force Richard Nixon to sign all the most important environmental legislation in American history, even though Nixon cared not at all about the natural world.

Finally, I’d like to make a larger point about gerrymandering. I see it as a mirror image of what we’ve done and are still doing to landscapes and powerless human communities in the Anthropocene. Gerrymandering is a colonial impulse. We carve up wetlands, grasslands, rivers, oil fields, and minority voting districts for single-minded power grabs, as if ecosystems and neighborhoods were merely resources for those in power to play with or destroy.

Remember that gerrymandering is mapping, and mapping is the application of knowledge to place. Used unethically, knowledge is the form of power that has long separated wealth from ordinary work. Remember that 20K investment by a CA politician to reduce her $2 million campaign costs? And the $30 million REDMAP investment that bought Republicans the House? Now imagine the rate of return the fossil fuel industry has earned on its mere millions spent mucking up the gears of democracy so that the industry remains unregulated even as the planet burns.

If you’d like to take a deep dive into gerrymandering, go to The Gerrymandering Project at FiveThirtyEight for a collection of podcasts, articles, and videos. For one thoughtful solution to the gerrymandering problem, read up on the Fair Representation Act (HR 3863), as explained here by FairVote.

And to keep an eye on the frightening prospect of the Supreme Court “turbocharging” partisan gerrymandering, read FiveThirtyEight’s assessment of Moore v. Harper, an effort by North Carolina Republicans to keep its extreme gerrymanders on the shaky grounds that only state legislatures, not state courts, can determine elections.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

Rewilding in Argentina is going well. Read this excellent and upbeat piece from the Guardian about the great strides made in protecting large parts of Argentina and reintroducing beautiful, important species back into these wild places.

Pee the Change You Want to See: from the Times, making your own fertilizer for the garden by collecting your urine will save both money and water.

“Unilever’s Plastic Playbook,” from Reuters, is an investigation into how Unilever and other plastic packaging producers are doing all they can to foil efforts to ban the sales of small disposable packets in the developing world.

For a deeper dive on the Court’s decision on the EPA and climate regulation, check out the Times article I mentioned in the first paragraph, and check out this piece from The Verge.

And for those of you wondering just how badly Justice Alito and five of his highly educated colleagues misunderstood or misrepresented American history in their decision to erase Roe from federal regulation, here’s a joint statement from two major professional historian associations explaining the Court’s mistakes, and here’s a glimpse of the real history of abortion in America during the late 19th century, when the 14th Amendment was passed. It’s from the Smarty Pants podcast at the American Scholar.

Nice focus for today's newsletter. Gerrymandering has always been a bipartisan pursuit as you point out. One recent difference is that with the power of computer programs, it has become so much more precise and effective.