Hello everyone:

As we approach the midterms, remember that democracy is more important than patriotism or politics. Democracy, in any of its forms, is like dirt. It may be messy, but without it nothing good grows.

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read some curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

My father, Vaughn Anthony, spent his career managing commercial fisheries for the U.S. government. The astonishing complexity of the work hinged on the capacity of scientists like him to turn raw data from sampling what boats were catching into a) assessments that determined how many fish were swimming in the sea and b) quotas that determined how many should be caught. It is difficult work and a fraught process– not least because of interference from politicians who were more concerned with votes than data – but he and his colleagues were very good at their job.

I wrote a little about Dad and his work in my inaugural essay for this Field Guide, noting that while I didn’t really understand the science, much less the math, what he told me about the importance of managing fisheries was my first lesson in what science does behind the scenes while our adolescent civilization lurches drunkenly onward.

That first essay was eighty weeks ago, on Earth Day, 2021. While I’ve learned and written a lot since then – see the index to the Field Guide’s first year here – nothing has altered the fundamental truth about our relationship with life on Earth that I mentioned then:

Now that we know that every living community on Earth is impacted by human activity through transformations of land, sea, and atmosphere, everything has to be managed. Anything less is privileging our right to decimate the array of life on Earth and undermine our own survival in the process… [T]he species we impact are being “managed,” whether we’re paying attention or not. So we can either do the science and make policy to manage all of it as best we can, as Dad said, or we can pretend otherwise and suffer the consequences.

Mostly it’s not the cod and the pandas and the mangroves we need to manage. It’s us. But as the wild world declines we do need to manage its stabilization and rehabilitation. I would like to say that we can simply step back and let the Earth thrive without us. Can’t we just protect rather than manage? There’s a large fraction of my soul that would like to see the widespread return of wild ecosystems and species living independently of this lurching civilization. And while a lot of that must happen, perhaps under the 30x30 movement or the Half-Earth project, there are a few problems with this notion.

First, any definition of wilderness that excludes humans ignores the ancient tradition of indigenous peoples managing their environment and threatens their descendants who now live on and wisely manage many of the places we hope to preserve and protect.

Second, there is no future in which any region of this planet is safe from human impact. That’s the definition of the Anthropocene. And it’s why, of the myriad ways in which our breaking planetary boundaries has disrupted the natural world, climate change is the most powerful and insidious. Bulldozers and pesticides and overfishing are local or regional, while a warming climate is universal.

Third, all of our increasing and accelerated impacts, particularly from climate change, have already tipped the natural world past the point of return to its pre-industrial state. There is so much still to cherish, protect, rewild, and renew as we strive to be an ecological and ethical civilization in a green world, but there is no path back to where we started.

So we have to consciously and wisely manage the globe that we are unconsciously and unwisely decimating. We are, to put it mildly, not yet qualified for the job. But we are capable. To maximize our potential, we need the economists to work for the ecologists, we need the politicians to work for the people, and we need the people to work for what the writer Ellen Meloy called their “biological address:”

Know where you are – your biological address. Get to know your neighbors – plants, creatures, who lives there, who died there, who is blessed, cursed, what is absent or in danger or in need of your help. Pay attention to the weather, to what breaks your heart, to what lifts your heart.

We need a plan at scale, one that points governments, policy makers, corporations, NGOs, nonprofits, and the rest of us in the right direction. For all the faults and fault lines of the U.N. climate talks, they at least represent a large-scale lurching in a better direction. Despite ongoing reports that we are failing to meet climate targets, we may yet bend the curve on our climatic disruption of Earth systems. But even that would not be enough.

We also need a simultaneous global plan to reverse the loss of life. Diverse plant and animal populations are under severe stress in every region of the planet. As those losses accelerate, so do our hopes of a stable, sustaining environment for our descendants.

That plan, should it come together, might come from the Global Framework for Biodiversity, which will, I hope, be hammered out and agreed upon this December in Montreal at the next UN Biodiversity Conference. That’s a topic that deserves an essay or three, but for the moment I want to look behind the curtain a bit and revert back to the scientific work being done to support the framework. Like the fish catch data that Dad used to build assessments and quotas, there is extraordinarily important work being done to understand the scale, depth, and speed of biodiversity loss around the world.

Which brings me to the Living Planet Index. The index and its reports are created by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and the Zoological Society of London, and are meant to serve as “a measure of the state of the world's biological diversity based on population trends of vertebrate species from terrestrial, freshwater and marine habitats.” In other words, by documenting the fate of selected populations of fish, birds, mammals, reptiles, and amphibians over time, the index creates a rough portrait of what’s happening with vertebrate life more generally.

Specifically, the index is based on assessments of 31,821 populations of 5,230 species. This means they’re not counting every single individual in a species, but tapping into long-term data about known populations of that species. For example, I dug into the data and found that one of the species on their list is Alosa pseudoharengus, the alewife, a migratory fish once very common in the northeast Atlantic. There are 25 selected population records of alewives in the data, including one just down the road here in Maine. Likewise, 34 multi-year records of common raven (Corvus corax) populations in North America and Europe were included.

A new Living Planet Report for 2022 is out now, and the loss it documents is heartbreaking. To the extent that the media are paying attention their dreadful headline is that wildlife populations have declined by an average of 69%. There is no way to make this headline more cheerful, because the data depict extraordinary losses in the natural world, but there is a way to make the headline more accurate. This is from the report itself:

The 2022 global Living Planet Index shows an average 69% decrease in relative abundance of monitored wildlife populations between 1970 and 2018.

Translation: Over the last fifty years, according to a large and diverse set of sampling data, these monitored populations show, on average, a two-thirds decline in their abundance. Since this is an average, we know that some populations declined by more than 69%, and that others showed smaller declines. And in fact, many populations and species increased or remained stable during the last fifty years. Which means that the population declines, where they exist, are substantially worse on average than 69% because they had to compensate for those other more modest population losses and gains. Populations in Latin America and the Caribbean, for instance, showed average declines of 94%, and populations of freshwater species throughout the world declined on average by 83%.

To be clear, the report is not saying that 69% of assessed species declined or went extinct. Nor is the report measuring the fate of species it doesn’t monitor – invertebrates, microbes, and species of every kind in less-studied parts of the planet – though it’s reasonable to assume a downward trend in many of those unmonitored species because the losses are happening on a global scale.

What the index offers, like basic blood work your doctor orders to get a snapshot of your general health, is a “comprehensive study of trends in global biodiversity and the health of the planet.” As such, it’s a crucial tool for setting policy. Which is why the Living Planet Index has been adopted by the Convention of Biological Diversity as a measure of progress for its goal of stopping biodiversity loss, and why it provides essential data for the Global Framework for Biodiversity.

But there is so much more to the Living Planet Report than the dire headline from the Index. I’ll start with its full title: Living Planet Report 2022 – Building a Nature-Positive Society. It has been written and illustrated for policy-makers and for you and me. It is not a wonky technical report. It is a message from researchers on the front lines who are honestly describing the crises we face amidst a radically disrupted natural world, and who are earnestly laying out the solutions necessary to move forward toward an ecological and ethical world.

Largely composed of three chapters – The Global Double Emergency, The Speed and Scale of Change, and Building a Nature-Positive Society – the report is more roadmap than litany of sorrows, and more focused on solutions than problems.

I’ll make a couple final points here as I close out this week’s writing, and then take a deeper dive into the report next week, but I also highly recommend that you read it. Download the pdf and spend a couple hours with it. I promise you it’s not as hefty or as daunting as it might seem, even for those of you who are extremely busy. It’s heavily illustrated, it’s readable, and it’s important.

The new Living Planet Report makes one thing very, very clear: The biodiversity crisis and climate crisis are equal and entangled threats to the stability of life on Earth (including our own), and they must both be dealt with immediately and simultaneously. This thread runs through the report, beginning with the first sentence of the Executive Summary:

Today we face the double, interlinked emergencies of human-induced climate change and the loss of biodiversity, threatening the well-being of current and future generations. As our future is critically dependent on biodiversity and a stable climate, it is essential that we understand how nature’s decline and climate change are connected.

The thread forms the basis of the first chapter (The Global Double Emergency) and then continues all the way to the report’s conclusion, titled The Path Ahead:

A global goal of reversing biodiversity loss to secure a nature-positive world by 2030 is necessary if we are to turn the tide on nature loss and safeguard the natural world for current and future generations. It must be our guiding star, in the same way that the goal of limiting global warming to 2°C, and preferably 1.5°C, guides our efforts on climate.

As some of you will remember, I wrote at length about the inseparability of biodiversity and climate in July, so I’ll only note here that it feels to me that the folks at WWF are working very hard to remind distractible policy-makers that climate is not the only unfolding tragedy on their existential to-do list. A single-minded focus on climate (to the extent that governments are focused on it) misses the point about the reality of the Anthropocene. Life on Earth is under severe stress from all of our activities, not just our greenhouse gas emissions.

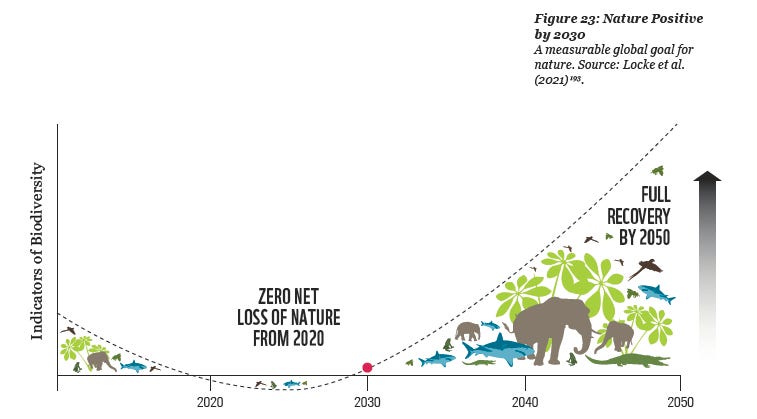

The appropriate civilizational goal, according to the report, is to match “net-zero by 2030” with “nature-positive by 2030.” I think “nature-positive” is a weak and calculating phrase, but it does capture the idea that we need, within the decade, to turn the corner and be rebuilding biodiversity rather than losing it. Here are two cute Living Planet infographics meant to portray that. The first indicates the 69% decline over the last 50 years, while the second picks up where the first ends, imagining an end to biodiversity loss by 2030 and major recovery by 2050:

Unlike the high value of merely reaching “net-zero” for emissions – the climate equivalent of “do no harm” – it’s not enough to simply stop harming the natural world. We need to restore, rehabilitate, replant, and rewild. The Living Planet Report goal they call “nature-positive” means no less than having more nature by the end of the decade than we have now. The scale of change required across all human systems to achieve that is daunting. It means abrupt and major shifts in how we feed, power, transport, and imagine our lives. Those future lives would be better lives, without a doubt, but the shift to get there, if we get there, will be seismic.

As with so many scientific reports these days, the tone of the writing in the 2022 Living Planet Report is no longer merely advisory. Science, if it is to be of use in this critical phase of the Anthropocene, must voice the clear and present danger it is assessing:

This is the last chance we will get. By the end of this decade we will know whether this plan was enough or not; the fight for people and nature will have been won or lost. The signs are not good. Discussions so far are locked in old-world thinking and entrenched positions, with no sign of the bold action needed to achieve a nature-positive future.

Managing resources in the Anthropocene, as I wrote 80 weeks ago, means that we must learn and practice restraint. Protecting life is about protecting it from us, which means we also have to redefine what “us” is. In other words, to become wise (or at least wiser) stewards of the world we have overrun, we must first learn to manage ourselves.

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

Are you unsure how best to commit yourself to helping society battle climate change and loss of biodiversity? Take this quiz from Yale Climate Connections to sort through your interests and abilities to determine your next step. If nothing else, read through it to understand the wide range of things each of us can do, personally and publicly, to improve the world.

From Science Daily, what appears to be a remarkable bit of good news on electric vehicle (EV) batteries. A breakthrough in charging technology will allow EVs to be charged in just ten minutes. There’s much more value in this than speed, though:

"The smaller, faster-charging batteries will dramatically cut down battery cost and usage of critical raw materials such as cobalt, graphite and lithium, enabling mass adoption of affordable electric cars."

More good news: From the Washington Post, the U.S. has for the first time appointed a diplomat for biodiversity. The appointment comes ahead of the next UN Convention on Biological Diversity (COP15) in December.

From Gyandemic, Anirban Mahapatra’s newsletter working at the intersection of science and society, a fascinating column about the connections between an early 20th century pregnancy test, the amphibian apocalypse, and the rise in malaria cases.

From Rewilding Earth, a memorial to the great eco-warrior, activist, wilderness-defender, and iconoclast Dave Foreman, who co-founded Earth First! and the rewilding movement, among many other remarkable environmental achievements. For Foreman there was no higher calling than the defense of wild places from human destruction.

From Anthropocene, an excellent assessment of a proposed plan to tax frequent flyers. While the program could hypothetically generate billions of dollars, there is little chance it could be fully or effectively implemented. The article is worth reading for the analysis of the larger aviation problem.

Thanks as always for an amazing essay. You put all the information together so clearly and so inspiringly. Looking forward to reading this weeks essay and the report itself.

I particularly loved this line: 'There is so much still to cherish, protect, rewild, and renew as we strive to be an ecological and ethical civilization in a green world, but there is no path back to where we started.'