Hello everyone:

This is the second half of my update on deep sea mining for polymetallic nodules. This may seem like an odd and arcane topic, but it couldn’t be more relevant to this moment - in terms of politics, technology, and environmental ethics - as we wrestle with the question of how best to enter the next phase of modern civilization.

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read some curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

I left off last week with this line about the prospect of deep sea mining amid all the questions about harms, corporate ethics, and regulations:

In the end, though, as with nearly all Anthropocene exploitation, the market will determine the outcome.

Which brings me to the question of whether the 21st century marketplace thinks polymetallic nodules can and should be harvested to build our battery-powered future.

An excellent 2023 Nautilus article questioned the two basic premises behind the push to mine the seafloor, that 1) the world desperately needs these minerals for the electrification of everything, and 2) there are billions of dollars to be made. Despite the hype, the need may be met elsewhere and the economics may be terrible. Let’s take these one at a time.

Unnecessary Expeditions

Despite the authoritarian movements working to upend alliances, reconfigure trade networks, and torque economics for fascist purposes, and despite the destructive last gasps of the fossil fuel powers-that-be, late 21st century civilization seems fated to be largely electrified and running on renewable energy. A rapidly heating atmosphere and acidifying ocean demand it, and now some of the technology to make it happen has passed the affordable tipping point.

Cheap solar is leading the race, with wind close behind, and advanced geothermal is a dark horse that may yet play a big role, all while nuclear (fission and fusion) spends trillions in an effort to catch up and take over. Hundreds of millions of electric vehicles will be built, grid-scale batteries will power up our nights, whole industries will convert away from gas and oil, and an increasing flood of “smart” devices will talk to us, to each other, and to the AIs running far too much of our lives.

An electrified culture is one built on mined and processed metals. When we discuss computers, solar panels, wind turbines, data centers, batteries, electric vehicles, and the electric grid itself, we’re really talking about a rapidly growing network of metal-infused technology.

In one of a recent series of excellent articles on this topic, Grist described the future this way:

Just as the 20th century was defined by the geography of oil, the 21st century could be defined by the new geography of metal — in particular by snarled industrial supply lines that often flow from the developing world to the developed world and back again.

The International Energy Agency has predicted that demand for the metals most essential for the transition - lithium, cobalt, nickel, copper, manganese, and various rare earth elements - could increase sixfold by 2050. This is the portrait of overwhelming demand that The Metals Company is leveraging to get their permits.

(This does not, however, mean that mining for renewables is as irresponsible and destructive as mining for fossil fuels. For several reasons, in fact, far less mining will be required for renewables.)

But new trends “could make deep-sea mining redundant,” as a Yale e360 article put it. A 2024 Rocky Mountain Institute report, “The Battery Mineral Loop,” describes that less dire future, at least for the metals associated with battery production. “Even as battery demand surges,” RMI writes, “the combined forces of efficiency, innovation, and circularity will drive peak demand for mined minerals within a decade — and may even avoid mineral extraction altogether by 2050.” Advances in battery tech (chemistry mix, energy density, and recycling) in the last decade have already reduced the need for cobalt, lithium, and nickel by 60%-140%. More specifically, they explain,

Accelerating the trend along six key solutions — deploying new battery chemistries, making batteries more energy-dense, recycling their mineral content, extending their lifetime, improving vehicle efficiency, and improving mobility efficiency — means we can reach net-zero mineral demand in the 2040s.

At that point, end-of-life batteries will become the new mineral ore, limiting the need for any mining altogether. We have enough to get there; our known reserves of lithium, cobalt, and nickel are twice the level of total virgin demand we may require, and announced mining projects are already sufficient to meet almost all virgin demand.

New battery technology is already emerging that uses less – or none – of the metals that The Metals Company would spend billions to fetch. For example, here’s a promising cobalt- and nickel-free battery technology designed at MIT.

If RMI is right that 1) we’ll need less than we thought and 2) we already have the resources we’ll need in more easily accessible places, than there seems far less need for massive, dangerous, and expensive deep sea expeditions to gather tens of millions of nodules, or as The Metals Company cutely describes them, “a battery in a rock.”

The analysis will be far more nuanced than I’m getting into here, of course. There are many minerals at play, and markets for minerals are nothing if not chaotic. Still, though, polymetallic nodules contain cobalt, nickel, copper, and manganese, and if the price for at least some of these metals remains low because demand is low, the economics of building an entire deep sea mining-and-processing supply chain look quite shaky.

Core Financials

As a member of the Deep Sea Mining Campaign interviewed in the Nautilus article put it, “There are just so many unknown factors in terms of understanding what the environmental impacts will be… but I think there are equally many things not understood in terms of what the economics will be.”

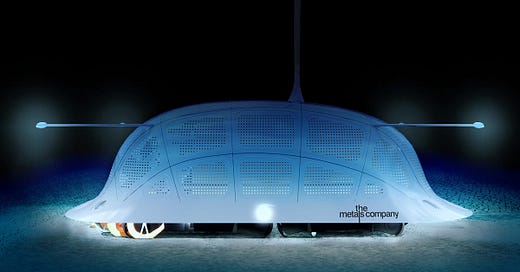

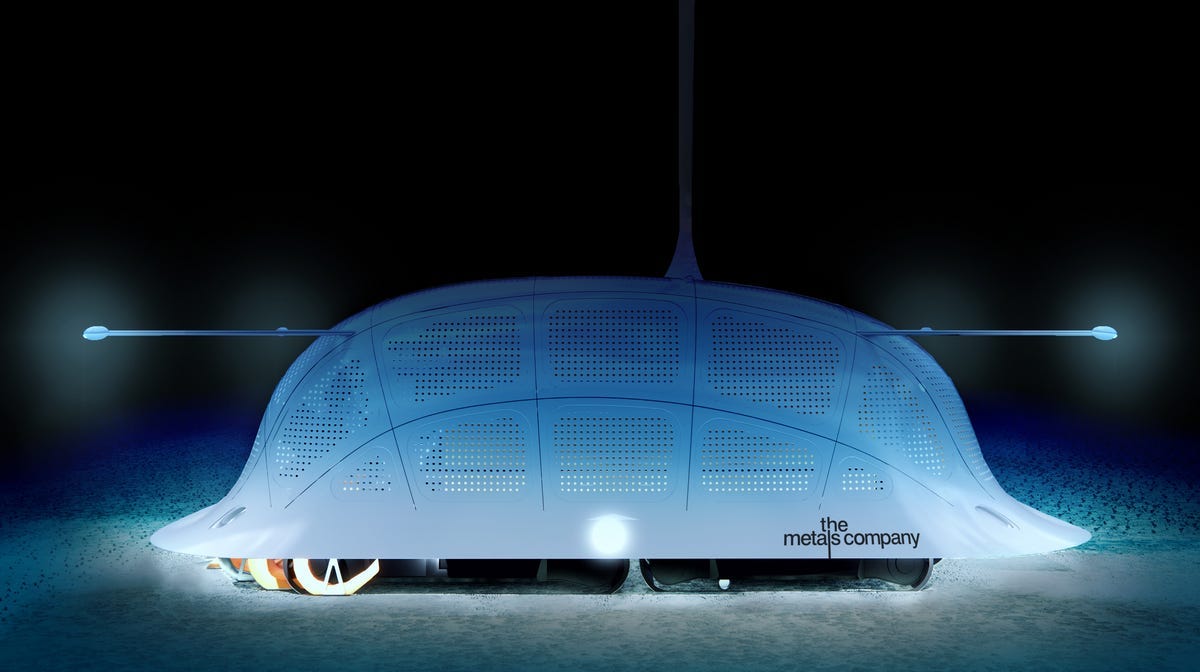

All deep ocean projects, whether for science or exploitation, tend to cost far more than planned. Ironically, the ocean will be cruel to the metal infrastructure of the metal-hunting deep sea operation. As

from the described it recently, while explaining why every wacky libertarian plan for creating independent constructed “nations” far out at sea has failed, “the ocean is a far less inviting place than architectural renderings tend to suggest.”The surface of the sea will toy with the vessels that need to maintain a constant connection with the harvesters. And operating complex machinery continuously in the great ocean depths will mean fighting against freezing temperatures, total darkness, corrosive salinity, and pressure intense enough to crush submarines. Mechanical failures and losses will be common. For this industry to profit, it will need long-term success and stability in the most difficult environment on Earth.

There are other financial variables, not least that deep sea mining companies may end up fighting multiple lawsuits, or eventually be found liable for impacts on commercial fishing or disruptions of carbon sequestration in the ocean. Also, these companies operating in international waters will be required by International Seabed Authority (ISA) regulations to share their profits with member nations of the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), but no one knows what that profit-sharing arrangement will be. Because of all these questions, the variable that matters most for the future of deep sea mining is whether the investment community thinks it’s a good bet.

Private equity investor and ocean explorer Victor Vescovo sharply criticizes the financials of seabed mining. You can watch his compelling talk at the Explorer’s Club on the topic. “I don’t think it works technologically or financially,” Vescovo told Nautilus. More importantly, “if you want to stop deep-sea mining,” he said, “you have to stop the funding.” Some of that has occurred already, when the shipping company Maersk dropped its investment in The Metals Company. TMC’s stock price dropped steeply from $10 in 2021, and has been hovering between$1 and $2 ever since. They lost $81 million last year. But if the Trump administration greenlights TMC’s permits, that may entice enough investment to launch the effort.

The Deep Sea Mining Campaign is paying attention, though, and offered a scathing response to TMC’s sudden pivot away from the ISA’s regulatory process and toward the Trump administration. Titled “Financial Desperation Is Driving TMC’s Reckless Push To Bypass International Law,” they describe the move as “a cynical, desperate attempt to stay afloat, not a credible step forward,” and “a red flag — one driven by investor panic, financial stress, and a complete disregard for multilateralism.” This announcement was made one day before the ISA met to discuss their application, a clear effort

to apply undue pressure to the ISA, [while] also attempting to circumvent international customary law and sidestep global scrutiny. In doing so, it opens itself up to a backlash from investors and customers alike… They’re waving around a potential U.S. permit system as if it’s a legitimate alternative to the international process. It’s not. It’s smoke and mirrors.

We may be at an inflection point for the mining of polymetallic nodules. The Metals Company may have found a regulatory path forward, and they may create the market they claim is necessary. Or the entire potential industry may wither in port, regardless of their permits, because it doesn’t really need to exist.

More likely, the mining may proceed, only to fade in the near future as it becomes unnecessary, leaving an essentially permanent swathe of destruction in deep-sea ecosystems millions of years old. And for what? For metals, as the Nautilus article says, “that will only be needed for a few more years.”

What We Have To Lose

What do we have to lose from the desecration of a small portion of an unseen world? None of us will ever see it in person, nor are we likely to suffer directly from the removal of millions of nodules from the sea floor. Isn’t deep sea mining better than the ongoing erasure of lush tropical forests that sit atop terrestrial deposits of these metals?

What we have to lose is the unseen world. It is unseen in part because it lies at the bottom of the ocean, but also because we often lack the empathy, insight, and cultural guideposts to connect our lives to the fate of life itself. If we’re honest, we scarcely know anything about where our land-based metals are coming from, or what devastation has been wrought in order to supply our metal-filled lives.

Perhaps, then, it’s best to keep the environmental horrors of mining located here on land, right where we can see them and, perhaps, regulate them.

But let’s review the list of threats to sea life from deep sea mining. It’s long and nuanced, but falls broadly into several categories:

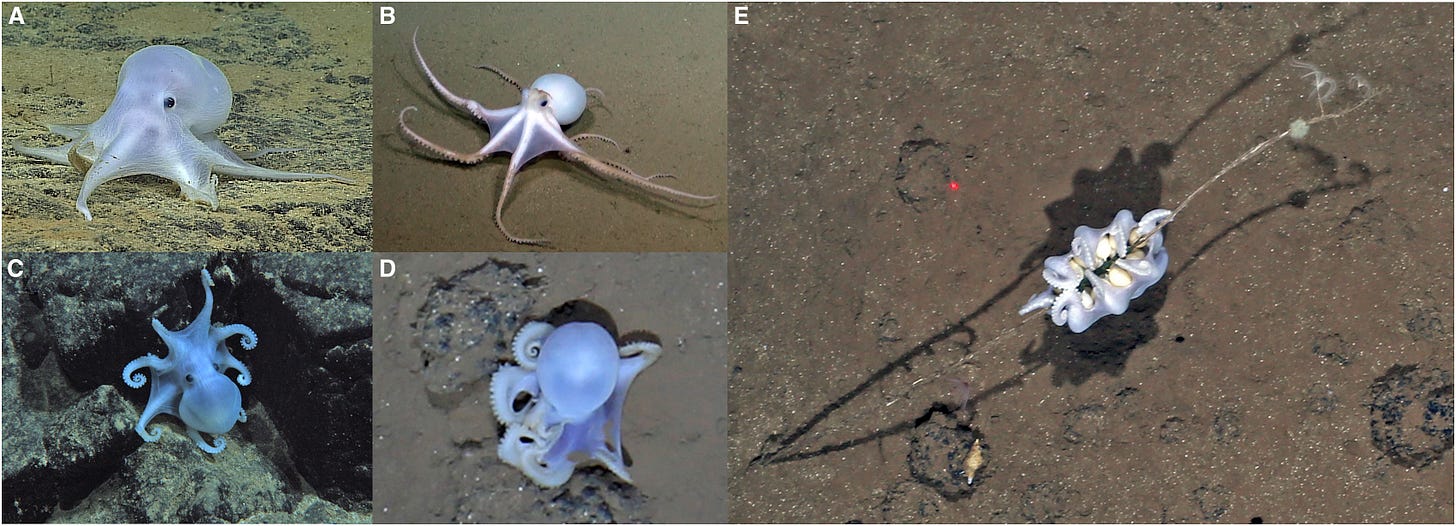

Wholesale destruction of diverse and unique communities of life by the bulldozing ROVs: Most species on the abyssal plain are unknown, incredible, unique, and unlikely to recover from mining activity for centuries or millennia.

Massive sediment plumes from both the ROVs and ship discharges: These would likely impact not only the mined areas but also thousands of square miles in the water column above the disturbed area and wherever currents would take the sediment.

Toxicity in the water column from sediment that disrupts life for fish and other megafauna.

Intense noise and light pollution in a habitat that has existed for many millions of years without either noise or bright light.

Large-scale release of carbon sequestered in abyssal sediments. As a Conversation article explains, phytoplankton at the ocean’s surface capture atmospheric carbon, which zooplankton consume and transfer through the food chain to fish and other predators. “When zooplankton and fish respire, excrete waste, or sink after death, they contribute to carbon export to the deep ocean, where it can be sequestered for centuries.”

Thus, any removal of the millions-of-years-old nodules and disturbance of the sediments would mean essentially permanent ecological changes, on site as well as throughout the water column and up and down the food chain. The upper reaches of the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ), the planned epicenter of Area mining in the Pacific – is crisscrossed by whales, whale sharks, leatherback turtles, tuna, seabirds, and many more, all of which are dependent on a healthy ocean.

And that’s just some of the charismatic marine fauna. If we look at the astonishing little things that make up most of marine life, we have a much better sense of what we have to lose:

The World As We Need to See It

The setting for this mining drama is a global ocean already severely threatened by pollution, noise, overfishing, radical decreases in fish and mammal populations, and spooky increases in temperature, acidification, and deoxygenation. It really doesn’t seem like the oceans need another destructive human activity.

The Metals Company does make the valid point that the greatest threat to the oceans is climate change, which generates both the warming and acidification of the seas. And they insist that the best way to accumulate the metals we need to shift away from greenhouse gas emissions is to suck them up from the ocean floor. It’s a peculiarly Anthropocene logic: The best way to save the ocean is to begin an entirely new exploitation regime of the oceans, even though we don’t know what we’re destroying or what the consequences of that destruction will be.

In response to the TMC/Nauru ploy a few years ago, 571 scientists and policy makers from 44 countries signed a statement arguing for a pause in the rush toward deep-sea mining. More importantly, perhaps, Sir David Attenborough, citing a massive 337-page report by the international conservation charity Fauna and Flora International, also called for a ban on deep sea mining until we know enough to make informed decisions:

The rush to mine this pristine and unexplored environment risks creating terrible impacts that cannot be reversed. We need to be guided by science when faced with decisions of such great environmental consequence.

And who among us wants to contradict Sir David Attenborough?

In fact, more than 30 countries have called for the ISA to issue a ban on deep sea mining. Volvo, BMW, Volkswagen, Google, and Samsung are among the companies which have pledged not to use seabed minerals in their products. We’ll need more campaigns like this to make prospective investors wary of the investment.

But of course this is really a civilizational question. We’re in a hole. Should we keep digging? If so, how should we dig, and where are we going?

There’s a tension here, as often happens, between the climate crisis and the biodiversity crisis. We must remember throughout this “clean” energy transition that the climate cannot be addressed without simultaneously defending life on Earth from our other bad habits. There’s no rationale for a Pyrrhic victory on fossil fuels if it comes at the cost of so much diverse, vital life.

Land-based mining or deep sea mining? The answer should be As little as possible of either, but my fear is that - as the demand for metals increases along with global temperatures and storm surges - the answer will be Take as much of both as we might need, and some more. It’s quite possible that in a decade or three, wide swathes of the abyssal plain will be toast. It’s dark and distant, it’s conveniently advertised as a dead zone, and it’s inhabited by unrecognizable life forms that seem irrelevant.

The octopus (seen below) that only broods its eggs on the stalks of sponges anchored to polymetallic nodules will probably find another sponge and nodule somewhere else, right? If not, we won’t notice.

In her New Yorker piece, Elizabeth Kolbert quotes Edith Widder, a brilliant scientist who specializes in bioluminescence – a crucial feature of life in the abyss – about a fundamental limitation in our own vision: “We believe we see the world as it is. We don’t. We see the world as we need to see it to make our existence possible.”

It’s not hard to imagine that in the Anthropocene, as we’ve rapidly changed what existence means both for us and for the rest of life on Earth, our blindness to the “world as it is” is at the root of our crises. To see more clearly, we need to learn how to dig deeper within ourselves, and to mine our culture for its purest empathy, because the only future that’s possible is one in which we remember how to live alongside the rest of life rather than at odds with it.

This means that, as we navigate the new geography of metal, we have to keep in sight all that is beyond our vision, including those marvels which exist deep beneath us in the dark.

For (much) more, read the Deep Sea Mining Campaign’s 60-page report from 2020, “Predicting the impacts of mining of deep sea polymetallic nodules in the Pacific Ocean: A review of Scientific literature.”

Or, for a fun and insightful take on deep-sea mining, watch John Oliver at Last Week Tonight tell the story with his usual brilliant wit:

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

Check out the newest edition of

from Owl Green, which offers news on events, new newsletters, books, and more from nature writers here on Substack. There’s some good news about snow leopards in Kazakhstan, too, just for good measure. If you’re not familiar with HOME, it is an incredibly comprehensive directory of nature writing on Substack, and a labor of love.From the Times, a major illustrated article on the environmental impact of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Ukrainian authorities are carefully gathering evidence from the widespread intentional destruction of their natural world to build a case for a newly established type of war crime: ecocide.

From Yale e360, scientists are still scrambling for answers and solutions to the great freshwater mussel die-off in the U.S. Southeast. As I wrote a couple years ago in a piece called “The Liver of the River,” these mussels are astonishing, fascinating, and incredibly endangered.

From

and , “The Faithful Leap,” another lovely nature essay, this one on a favorite topic of mine: tree swallows.From

and , “Bird by bird, step by step, problem by problem,” a lovely reminder that the way to face up to the kinds of overwhelming tasks (planetary, political…) that confront us now is to nibble away at one task, then the next, then the next, rather than be paralyzed by the full scale of it all.Speaking of which, here’s a cluster of Trump-related environmental disaster stories in the making:

From High Country News, the administration has cut funding for cleaning up and plugging orphaned oil and gas wells.

From the Guardian, likewise for hundreds of conservation projects funded around the globe by USAID and other federal agencies.

From the Center for Biological Diversity, an analysis of the administration’s terrible proposal to sell off federal land near Western cities and towns with more than 5,000 people. This could include national monuments, wilderness areas, and critical habitat for endangered species:

Nearly 500 separate areas deemed worthy of protection by the Bureau of Land Management or Congress, including dozens of national monuments and protected waterways, fall within the Interior Department’s target to sell roughly 400,000 acres to local governments and private developers.

From the Post, another miserable bit of Elon-Musk-related news, this time on remote Pacific islands where the U.S. military is planning to build rocket pads to practice landing SpaceX rockets in preparation for using these massive rockets to move military cargo around the Earth. That’s dumb enough, but the real problem for now are the 1.5 million seabirds in “protected” nesting habitat who have no other island to go to if scared off by the rockets. The military is claiming no harm will be done, but as a biologist who actually knows the island said, “Just us riding our bikes around the island would flush birds off their nests.”

From Quanta, new research on the evolution of intelligence in vertebrates further reminds us that our particular primate brains have no unique claim to intelligence, and that it evolved separately in birds and mammals.

Thanks you for bringing us this in depth look at ocean floor mining. It’s heartbreaking to watch our “business as usual” mindset keep plowing ahead without thought for life.

As a species we must figure out "what are people for?" Wendell Berry posed that question I believe and it's a deep one to which we have no answer. What are we here for? Until we know, we are destructive Interlopers on our own planet.