The Patience Required

12/11/25 - A holiday treat of remarkable art

Hello everyone:

As an expression of gratitude for the Field Guide community, and in recognition of the frequent heaviness of the work at hand, I’m offering you something light, quick, and beautiful in this holiday season. Some of you will remember it from last year, but I’m confident that it’s worth another look.

I had intended to send it out on Christmas or New Year’s, which both fall on my Thursday publication days, but have decided to take those two weeks off instead. You don’t need to feast on my large essays during such a busy time, and I’ll be busy with family too.

I’ll be back next week with one final essay for 2025. Until then, please enjoy this collection of Sherrie York’s remarkable art.

As always, please remember to scroll past the end of the essay to read this week’s curated Anthropocene news.

Now on to this week’s writing:

Our friend Sherrie York lives nearby in a small house tucked away on the edge of field and forest, here on one of midcoast Maine’s many peninsulas. In it, she works quietly and very, very patiently on her remarkable linocut prints of birds, flowers, and other natural wonders she encounters on her walks in this wondrous place. I’m particularly fond of her work with birds on the water.

If these prints were paintings, they’d still be marvelous, but they’re much, much more complex than that. To me, what Sherrie does with the linocut process to produce these subtle, joyful, textured portraits of the wild world is simply astonishing. Linocut printmaking is ridiculously complicated, a high-wire act that requires an artist’s vision, a draftsman’s drawing skills, a painter’s ability to build an image up through multiple layers of color, and a sculptor’s capacity for creation through subtraction.

And there’s one more twist: What she carves is not what we’ll see, because the linocut is a mirror image of the print.

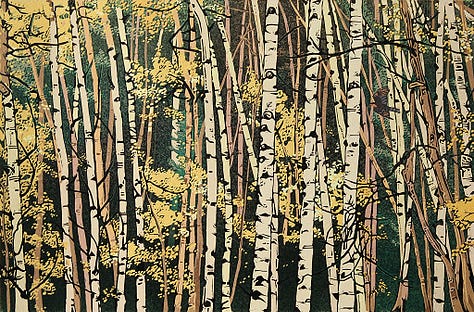

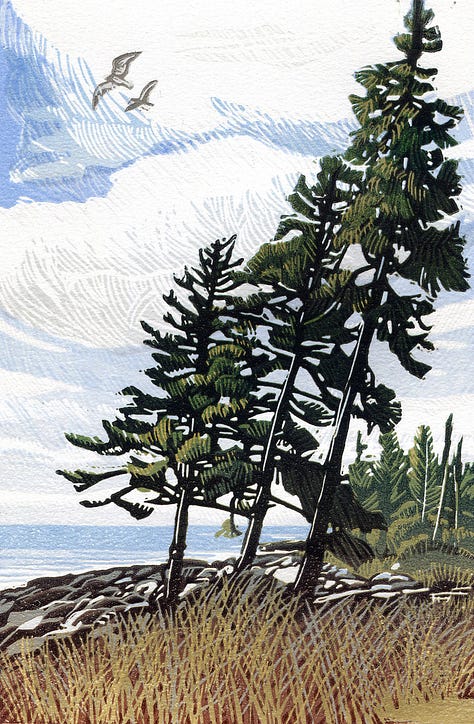

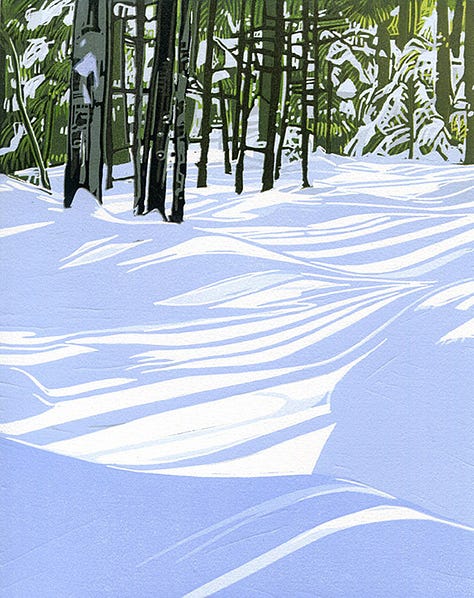

Look at the play of light and motion in these images, and then imagine you’ve made them by carving and inking in many, many stages:

There is an enormous amount of time invested in each image, time that passes in steps that are slow and then sudden, slow and then sudden. Every color you see in these prints represents a unique stage in the process that, once set, cannot be revisited, because all areas with that color are laboriously carved away by hand before the next color can be worked on. Or as Sherrie writes, “the artist carves away any areas of the block that they do not want to print.”

She can modify a specific color during its stage, but not after. The image is printed not just once at the end, but over and over through color layer after color layer, for each one of the limited number of prints she’ll make from it. And, after each layer is inked on, a print must hang and dry, sometimes for days.

On the Process page of her website, Sherrie begins with a simple definition of a linocut - “a type of relief print created by applying ink to the raised surface of a carved piece of linoleum, and using pressure to transfer the inked image to paper” - before going on to provide more detail. One thing she clarifies is the idea of a linocut “print”: unlike the unlimited copies of a painting, a linocut print is actually an original, unique artwork.

There’s an excellent brief description of the linocut process on her Process page, but I also recommend her cheerful 15-minute video, Reduction Linocut Process: Columbine.

I love the presence of each bird in her images. They belong in the world, and in the world Sherrie has created.

She works wonders with birds in other settings (“Chasing Daylight” is a favorite of Heather’s and mine)…

with landscapes…

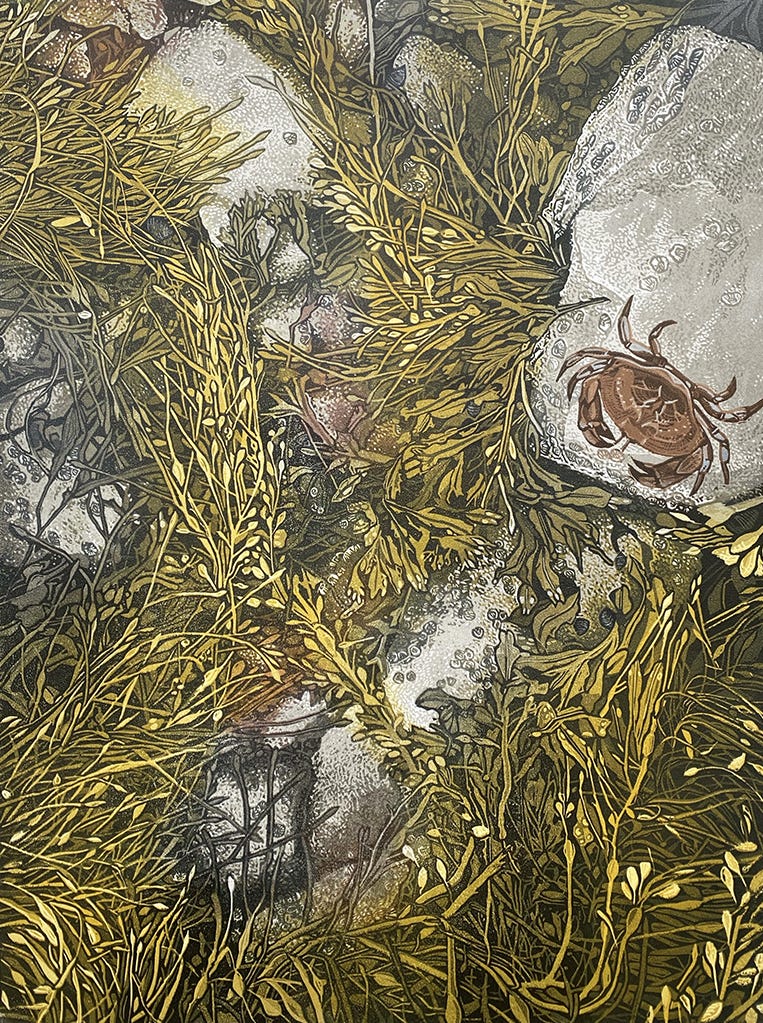

and with the textures of life that we don’t pay attention to until an artist reveals them to us, like this remarkably detailed glimpse into the patterns of a tidal pool:

In writing about the inspiration behind this particular print, Sherrie reminds us that

The intertidal zone is a special and constantly changing place. Completely underwater for parts of each day, and exposed to the extremes of heat, cold, wind, rain, and snow in between, organisms that make the intertidal zone their home must be resilient and adaptable... holding fast when necessary, and moving or letting go when the time comes.

I see resilience and adaptability also in Sherrie’s complex linocut process, crafting in incredible detail one day and then, as the ink dries and the work reveals itself in slow stages, letting the art take on a life of its own.

And, in the bigger picture, both the intertidal zone and the nature of Sherrie’s work speak to this turbulent moment - in both human and Earth history - that you and I are awash in. I doubt I’m the only one who feels the tide of news and Anthropocene science surge roughly over me throughout the day, leaving me either underwater or exposed to the extremes of the new world we’re forging from our mistakes.

And that’s where good art, and good acts, undertaken with the patience required, become necessary. To protect, conserve, rewild, and otherwise respect the inherent beauty of the living world, we need to infuse our communities with a hard-working creativity that feeds the zeitgeist which in turn helps shift society toward good policy. I make no claim here for the power of art to fix the Anthropocene, but that doesn’t make it any less necessary.

You can’t swing a cattail here in midcoast Maine without hitting one of the boat builders, painters, potters, musicians, sculptors, craftspeople, and writers who call the nooks and crannies of this coastline home. Here, as among all the peoples of the world, so many of us are trying to live reasonable, less harmful lives that are respectful of the community of life that surrounds us still.

These Maine artists are all doing beautiful work, but I want to highlight Sherrie’s images here because her focus isn’t a human view of a human world ornamented by nature. She looks at the real world in and of itself, and helps us to see it, to move closer to it, step by step.

Sherrie’s art won two awards in national juried shows just this year, at the Hudson Valley Art Association 92d Annual Exhibition and the Rockport Art Association & Museum National. You can read more about Sherrie and her award-winning work on her website.

Many of these prints - and plenty of others - are available for purchase there, under the Portfolios tab. Her work deserves your support. Enjoy.

Here’s some of her most recent work:

Thanks for sticking with me.

In other Anthropocene news:

Have you been dreaming of leaving the U.S. rather than letting your health suffer as you live through the nightmare of the second Trump administration? My friend Jennifer Lunden has done it, and her new weekly Recovering American blog will tell you all about her move to France. Lunden is an excellent writer and the author of a book I’ve mentioned here more than once: American Breakdown: Our Ailing Nation, My Body’s Revolt, and the Nineteenth-Century Woman Who Brought Me Back to Life, a “Silent Spring for the human body” in a toxic age of industrial pollution.

In an important, informed commentary from Hannah Ritchie at Sustainability by Numbers, she lays out her rationale for why, “for the first time in history, we can improve human well-being while reducing our environmental impact.”

Two innovative ideas from Anthropocene: First, a suggestion that sports teams become advocates for the conservation of the animals they use as their mascots. And second, research has found that biochar made from coffee grounds can be used to replace 15% of the sand in concrete while making the concrete 30% stronger and reducing CO2 emissions by 26%.

From the Times, a new comprehensive look at the effects of deep sea mining on the ocean floor finds that both abundance and diversity of life decreases sharply. Funded by The Metals Company (TMC), the company now posing the primary threat to life in the Pacific deeps, the research nonetheless is independent and unlikely to help TMC’s case. If you’re new to the Field Guide, read my work on deep sea mining here and here.

Two large good-news stories from Vox on the welfare of farmed animals: First, in what may serve as a death knell for the European fur industry, Poland has just passed a law phasing out fur farming over the next eight years. And second, there is a movement forming to stop octopus farming before it starts. The primary threat is that a Spanish company wants to build a facility in the Canary Islands that will grow and slaughter a million octopuses a year. Maybe there’s hypocrisy in banning this industrial slaughter but not that of pigs, cows, and chickens, but it’s a start.

From Inside Climate News, a massive new high-tech port built in Peru by the Chinese will revolutionize trade between South America and Asia, but it may plunder the Amazon to do it. If you build it…

From the Guardian, the root cause of much of what ails humanity and the Earth - inequality - has gotten worse. Data from the World Inequality Report show that “fewer than 60,000 people – 0.001% of the world’s population – control three times as much wealth as the entire bottom half of humanity,” and “the top 10% of income-earners earn more than the other 90% combined.”

And speaking of dramatic inequality and the too-cozy relationship between billionaires and government, read this investigative piece from High Country News and ProPublica on the massive federal subsidies - paid by our tax dollars - for wealthy ranchers grazing their herds on public land at extremely reduced rates. Two-thirds of public land used for grazing is controlled by just 10% of permit holders.

Astonishing in so many respects, but for me it's her conveyance of the interplay between light and water. Dazzling, alive, mysterious.

I hope you have a wonderful two weeks off! Thank you for sharing the artwork of Sherri York...it is amazing!! She makes the process sound and look easy. Maybe for her it is, but I'm still scratching my head trying to figure out how she creates such beautiful images.